Our Man in Beirut

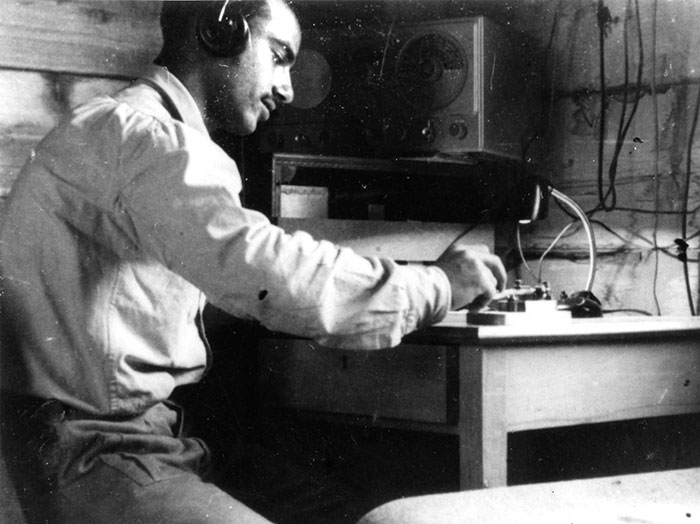

Some of the most dramatic moments in Matti Friedman’s excellent new book about the men of the Arab Section, an espionage unit that served Israel in the months immediately before and after statehood, take place at the border. These immigrants, newly arrived from the collapsing Jewish communities of the Arab world, found themselves asked to turn around and head back into what was now enemy territory. Equipped with false identities, they were trained to gather intelligence and carry out occasional missions of sabotage. Making the crossing, often in the guise of a fleeing Palestinian refugee, could be dangerous. “[O]ne slip, one second, and you were in a nightmare. There was no way back through the gate. The only way out was forward, into enemy territory.”

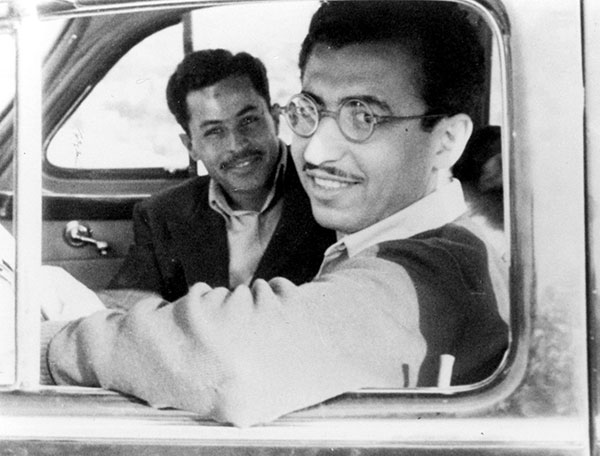

But they could hardly let their guard down once they were living in countries that were at war with Israel from the day it was founded. Anything could set off the suspicion of their neighbors. Damascus-born Gamliel Cohen had assumed the identity of a Palestinian named Yussef and ran a small candy shop in Beirut. One day, he found himself questioned by a nearby merchant: “You know what? . . . So far we haven’t heard you say a word about your family. Not a word.”

“This was an innocent question, and also a gun at Gamliel’s temple,” Friedman writes. But Cohen had an answer at the ready: “I’m miserable inside . . . All I can tell you is that my whole family was killed, that no one is left, that I myself barely escaped and am barely getting by. I have nothing else to say.” That shut the nosy neighbor up. But the danger was omnipresent. The Arab Section, suggests Friedman, in one of the book’s nicer lines, “needed men idealistic enough to risk their lives for free, but deceitful enough to make good spies.”

In another case, one of the spies elicited suspicion in a Beirut boarding house because he cleaned himself in the toilet not with water but with paper, “a habit that was Western and middle class,” leading another resident to speculate aloud that he was a Jewish spy (and leading him to immediately seek out other living arrangements). Shimon Somech, the Baghdad-born trainer of the Arab Section, described the ideal recruit to his unit as “a talented actor playing the part twenty-four hours a day, a role that comes at a cost of constant mental tension, and which is nerve-racking to the point of insanity.”

Friedman believes that both Israelis and non-Israelis would understand the country better if they were more attuned to that part of the Jewish population that has its origins in the Islamic world. Certainly, it’s true that the culture, history, values, and traditions of Mizrahi Jews were for too long given short shrift, even as they became the majority of Israel’s Jewish population. The men and women who founded the state and established its most important institutions (including the

Israel Defense Forces, the Histadrut labor organization, the universities and kibbutzim) were for the most part of European birth or descent, and they deserve enormous credit, not only for those accomplishments, but for successfully taking in and settling some 800,000 Eastern Jews virtually overnight when the latter were basically expelled from their host countries. But it’s also true—and by now widely acknowledged—that the process of immigrant absorption showed little

respect for or interest in the culture and traditions those Jews brought with them. They were mostly relegated wholesale to new settlements away from the center of the country and were expected to adopt the majority culture.

The Jews of North Africa and the Middle East came from a world where respect and pride were pre-eminent values, and they were plunked down in a society that had neither the time nor the inclination to take pains to avoid humiliating them. The resentment that this treatment bred is still with us today, as are many of the educational, economic, and social gaps that could by now have been overcome.

Although the Arab Section played a foundational role in Israeli spycraft, its glory is, unsurprisingly, almost entirely unsung. Also called the “Black” Section (“shachor,” in Hebrew), presumably because of the dark skin of most of its members (its name that later morphed into the “Dawn” Section, since “shachar,” the Hebrew word for “dawn,” sounds like “shachor” but is less offensive), the unit took shape within the Palmach, which, to this day, is remembered as the quintessential icon of the seemingly invincible Ashkenazi elite that led Israel and its military in their first decades.

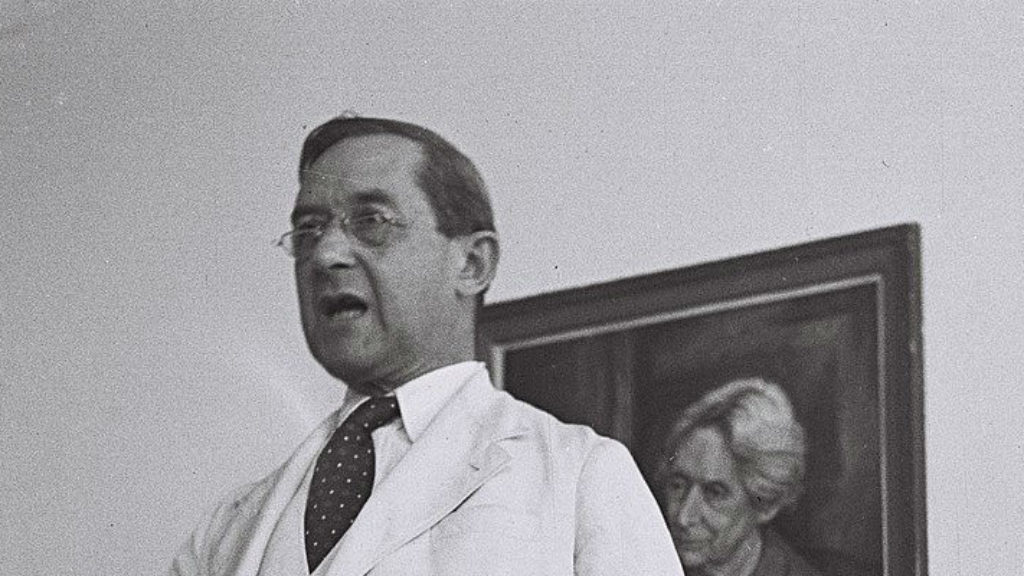

Friedman makes his story compelling by focusing on the lives of four members of the section. Gamliel Cohen (nom de guerre “Yussef”) grew up in Damascus and was sent to serve the state-in-the-making in Beirut in early 1948. There he was joined by Isaac Shoshan (“Abdul Karim”), an Aleppo native; Havakuk Cohen (“Ibrahim”), from Yemen; and eventually by the Jerusalem-born Yakuba Cohen, aka “Jamil.” (None of the Cohens were related.)

All of these men were “mista’arvim,” a Hebrew word meaning “Ones Who Become Like Arabs.” You will be familiar with the concept if you’ve seen episodes of Fauda, the hit Israeli TV series about contemporary warriors who impersonate Arabs in order to infiltrate Palestinian terror groups. But Gamliel, Isaac, Havakuk, and Yakuba lacked the backup or technological support that Fauda’s heroes can rely on. They had only their wits and their native knowledge of Arabic to help them maintain their subterfuge.

They also understood that if they were caught, there was little their country would be able to do for them. In fact, initially, “They had no country”—hence the book’s title—since “in early 1948, Israel was a wish, not a fact. If they disappeared, they’d be gone.”

Yakuba Cohen had a habit of attending public hangings during his time in Beirut, because he “thought one day it would be him standing there, and he wanted to know how it would feel.” He later described how he pictured himself shouting out, “Long live the State of Israel,” in Hebrew, before the gallows plank was removed below him, until he realized that acknowledging his real identity, even in death, would only endanger his colleagues. Instead, he resolved, “I’ll keep quiet and they’ll bury me like a dog.”

The legend that many still tell themselves about Israel, writes the author, is that “people like our four spies came from the Islamic world and joined the story of the Jews of Europe. But what happened was much closer to the opposite. The Palmach, a brash militia animated by the revolutionary energy of mid-20th-century Europe, is famous as one of the country’s founding myths. The Arab Section, a tiny outfit of Middle Eastern Jews cautiously traversing their own dangerous region, isn’t famous. But the Palmach explains little about Israel now. The Arab Section explains a lot.”

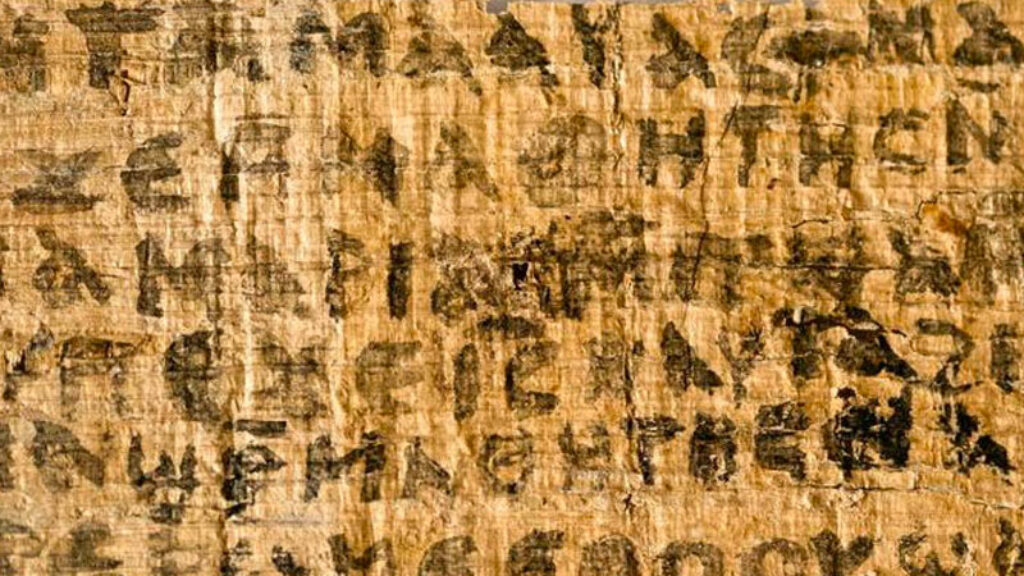

The importance of the Mizrahi experience for a true understanding of Israel and its place in the modern Middle East has been a concern of Friedman’s since his first book, The Aleppo Codex (2012). There he told the story of the eponymous 10th-century copy of the Hebrew Bible, the most authoritative version of the Masoretic text known to exist. Friedman described the journey of the book from its creation in Tiberias to its transfer to Cairo after the Crusader conquest of the Holy Land in 1099, and eventually its move to Aleppo, whose ancient Jewish community guarded it from the 15th century until 1958, when it was smuggled into Israel for safekeeping. During its final journey, or more precisely, probably just after its arrival in Jerusalem, more than half of its pages disappeared, a disappearance that was retrospectively blamed on marauding Syrians in the anti-Jewish riots of 1947. Friedman makes a strong case that the missing leaves were stolen by the then-director of the Ben-Zvi Institute, which had been entrusted with its preservation. A restrained, often ironic writer, Friedman portrayed an Ashkenazi Zionist establishment that not only felt entitled to deceive the Aleppo community, whose rabbis it viewed as primitive, into giving up its most cherished possession, but was then unwilling to acknowledge or investigate the theft carried out by one of its own.

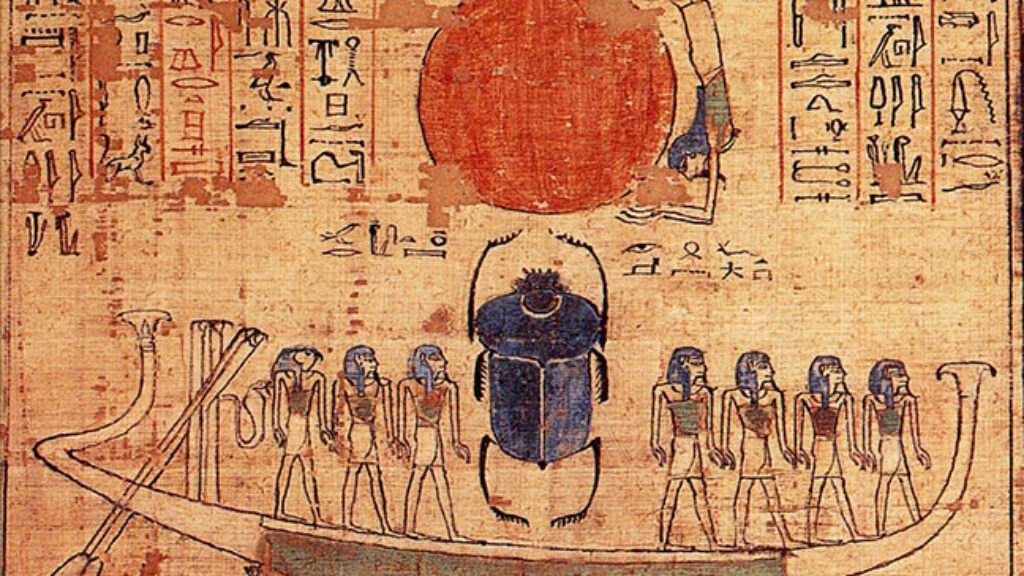

In his 2016 book, Pumpkinflowers, about the small IDF outpost in Israel’s self-declared “security zone” in southern Lebanon where Friedman served as an infantryman shortly before Israel’s final pull-out from Lebanon in 2000, he writes about the folly of the type of wishful thinking that imagined Israel as poised on the brink of an era of peace. The country, he writes, was entering a new era, but it was one “in which conflict surges, shifts, or fades but doesn’t end, in which the most you can hope for is not peace, or the arrival of a better age, but only to remain safe as long as possible.” Now, in Spies of No Country, Friedman suggests outright that if Israel had paid more attention to the people of the Arab Section—and to its Mizrahi Jews in general—it would have understood this, since they had had a presence in the region since before the dawn of Islam, in the 7th century.

The Jews who came to Israel from the Islamic world brought a deep distrust of that world; an appreciation of the importance of religion, which Westerners often don’t understand; and the knowledge that nothing good befalls the weak.

Elsewhere, he writes that “the belief that eventually the Arab world would make peace with a Jewish state as the world moved toward greater amity” was an idea from Europe, and today it’s dead.

It’s not that the mista’arvim, or Eastern Jews in general, hated Arabs. Gamliel Cohen, for example, commented, late in his life, that, “Hatred is between nations, not people . . . so when someone talks about ‘the Arabs,’ I always say that among them are people who are kind and good—I haven’t found friendship among Jews as much as I’ve found among Arabs.” At the same time, Gamliel could not forget a scene he witnessed in the train station of Tulkarm (in today’s West Bank), even before Israel’s establishment. A nationalist leader had been allowed by the British to return to his hometown from exile. There he was greeted by a crowd crying, “Nahna nedbah el-yahud! We’ll slaughter the Jews!” It was a scene that, Gamliel told an interviewer in the 1990s, “affects me to this day . . . [Extremists] live on a completely different level . . . They read their religion in completely different letters.”

Friedman may read more political, historical, and strategic significance into the experiences and reflections of his old Mizrahi spies than they can sustain, but he is undoubtedly correct that their stories are an unjustly forgotten—and fascinating—aspect of Israel’s founding. His deeply researched book is not only enjoyable but groundbreaking.

Suggested Reading

Temporary Measures: Sukkah City

The reimagining of an ancient architectural ritual.

The Professor and the Con Man

The saga of the papyrus that became famous as the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife began with an email sent to Karen King, a distinguished Harvard professor, in July 2010. The subject line read, simply, “Coptic gnostic gospels in my collection.”

Exodus and Egyptology

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel shows why the plagues were chosen and how the Israelites sang at the reed sea.

A Good Second Choice

Yirimiyahu be-Tzion is a solid work of intellectual history, devoted above all to understanding Judah Magnes as he understood himself, sympathetic but honest, and attentive to the weaknesses as well as the strengths of his thinking.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In