A Letter to Mama

In “A Letter to Mama,” which appears here for the first time in English, Isaac Bashevis Singer tells the story of Sam Metzger, who, having immigrated to America, marries and establishes a successful clothing shop with his wife, Bessie, without ever writing home to his widowed mother in Poland. Now almost 60, unhappy in his marriage and estranged from his daughter, he is overwhelmed by the enormity of his neglect of his mother in Poland and his abandonment of Yiddishkeit. “In his effort to forget,” Singer writes, “Sam had become a traitor to his people.”

Singer’s postwar fiction about America was generally set in the contemporaneous present, describing the new American lives of refugees and survivors of the Holocaust. “A Letter to Mama,” which was originally published in the Forverts on October 29, 1965, is something of an exception. Its mention of Hitler’s threats to invade Poland and the vivid description of the Yiddish literary scene in the Café Royal clearly place it in the late 1930s, and yet other details and cultural markers have an anachronistic feel. For instance, the Metzgers’ comfortable house in a small Illinois town is described as being a “$60,000 home,” but in the late 1930s, $60,000 would have bought a mansion in the Midwest. Less definitively, Sam’s daughter Sylvia goes to school in California, is engaged to a non-Jew, and admits to her mother that she has had an abortion, all of which certainly could have happened in the 1930s, but would be more culturally typical of the mid-1960s when Singer wrote the story. Perhaps these somewhat incongruous details are meant to underline its dreamlike atmosphere.

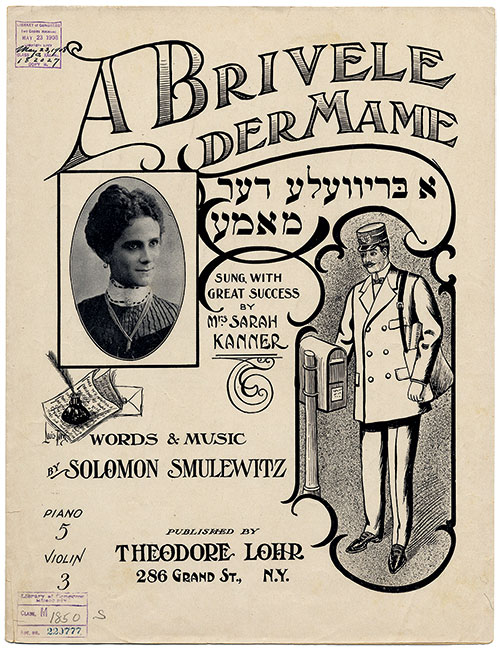

The most powerful cultural reference is in the story’s title. The song, “A brivele der mamen” (A Letter to Mama), was composed by Solomon Shmulewitz in 1907, and tells the story of a young man who immigrates to America, finds success, but ignores his mother back in the Old Country—until one day he receives a letter saying that his mother has died and that her last wish was for him to say Kaddish for her. More haunting than the reference itself, which Singer would have expected his Yiddish readers to recognize instantly, is the fact that the song eventually inspired a film of the same name, which was one of the last Yiddish films to have been produced in Poland, in 1938. It opened to packed theaters in New York the following year at more or less the moment in which the story is set. With a single stroke, Singer evokes not only the difficult experience of separation caused by emigration from Poland, but also the finality of that separation for those who found themselves on the other side of the Atlantic with the outbreak of the Second World War.

In some ways this must have resonated with Singer’s personal experience. When he left Poland in 1935, he left behind his mother Basheve, with whom he was very close (he famously incorporated her name into his pen name), and though he did write to family and friends from America, he was a poor correspondent. A letter from his mother, undated but appearing in the archives among envelopes dated September 1936, puts it bluntly: “you don’t have to make a fuss if a letter is late since you yourself write seldom too. If you wrote more often, I’d also write more, God willing.” In the early 1940s, Singer’s mother and his brother Moyshe were evacuated by the Soviets in cattle cars to the Jambyl region of Kazakhstan, where they died of illness and starvation.

It is suggestive that just two days before “A Letter to Mama” appeared Singer published another piece, “A Story that Mama Told Me,” which portrays a young man who, having heard about the wonders of the Garden of Eden his whole childhood, decides that when he grows up, he wants nothing more than to die. “A Letter to Mama” itself is exceptional in Singer’s body of work in its attempt to portray the conscious experience of death and the soul’s passing into the world to come.

—introduction by David Stromberg

The older he became, the less able Sam Metzger was to understand why he had never written to his mother after leaving Krasnobrod for America. This “letter to Mama,” which he never wrote, became the bane of his existence. Granted that he disliked writing letters and that the first years in New York he used to work fifteen hours a day in a sweat shop. Still, to leave his widowed mother behind in Krasnobrod and never write her so much as a single word, he had to be out of his mind. Sam could not fathom how this came about, although he had brooded over it many sleepless nights.

At first, it was simply a manner of putting it off. Then he seemed to forget about it altogether. At night, while trying to fall asleep in Moishe Leckechbecker’s alcove on Attorney Street, along with three other boarders, he would think of it. In the morning, he would forget again. Later the nagging sense of shame turned into conviction that it was already too late. A devil possessed him who wouldn’t let him take a pen in hand. In New York at the time, they were all singing a popular Yiddish song which went: “Why delay? Write your mother today.” From the Yiddish theater stage, from Second Avenue cabarets, in the workshops on Grand Street, from record players blaring in homes, the song followed him everywhere.

Perhaps that was the reason Sam left New York. He got as far as Chicago, where he became a peddler. He knew no fellow countrymen from Krasnobrod there. He married a Lithuanian girl, a plump orphan named Bessie, and his business prospered. Bessie had saved nine hundred dollars with which she opened a women’s wear shop. Sam and a partner bought a store which handled the same sort of merchandise.

Miracles didn’t happen to Sam. He didn’t become a Rockefeller. He and his wife needed little and managed to earn three or four times more than they needed. When they were in their thirties, a daughter was born to them whom Bessie named Sylvia—after her own mother, Sarah. The couple hired a Polish servant, Antosia, who became devoted to the child. Antosia’s husband, a coal miner, had died in a pit. They had had no children. Antosia was more trustworthy than a relative of the family could ever be. She ran the household, cared for Sylvia, and was frugal. She invested her savings in Sam’s business, eventually accumulating several thousand dollars. Whenever Sam would try to pay her salary, she would argue, “What good is money to me? I have everything.” She drew up a will in which Sylvia became her sole beneficiary.

Later, Sam bought a department store in a city in Illinois where no more than twenty Jewish families lived, mostly business people, a few professionals, a doctor, a dentist, and a veterinarian. During the day, the men were occupied with their work. At night, they played cards. After a while, they hired a rabbi and established a synagogue, but there were never enough men attending to make up a minyan, except for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The rabbi, a bachelor, was openly living with a Gentile girl. Everyone called him by his first name, Jack. In the late twenties, fundraisers began coming from Chicago, New York, even from Palestine, all demanding large donations. They reprimanded the Jews for not giving their children a proper upbringing. But there were hardly any Jewish children left, only grandchildren of mixed marriages.

Sylvia had grown up and had gone off to college. Sam was approaching sixty. The years had been filled with business, card playing, and an occasional trip to California or Florida. Antosia had died and Sylvia had inherited her money. Sam set an elaborate tombstone over Antosia’s grave in the Catholic cemetery.

Over the years, Sam had managed to avoid contact with anyone from Krasnobrod. He had no idea whether his mother had died and whether he should say Kaddish and light an anniversary candle for her. He kept from mentioning the word Krasnobrod among the town Jews, even though they probably wouldn’t have known where it was since they all were born either in Lithuania or Rumania.

In his effort to forget, Sam had become a traitor to his people. Several of the Jewish spokesmen who visited the town from time to time would refer to the community as godless, materialistic, money-grubbing. The other men resented these rebukes, but Sam Metzger reluctantly agreed.

During the day, Sam was too busy to think about these things, but at night, after the card playing, lying beside Bessie in the upstairs bedroom, his thoughts would assail him like a swarm of locusts.

Sam owned a $60,000 home with a large garden and a two-car garage for his and Bessie’s Cadillacs. Sylvia was at school in California. Bessie now needed a pill before going to bed. Sam was in the habit of taking a warm bath at bedtime. This late-night bath had become for him an hour of reflection.

Every time he undressed and saw himself naked in the mirror on the dresser or on the door, he would make a short reckoning of his life. He had been lucky but had aged prematurely. His round, bald head was ringed with sparse white hair. His crooked nose was covered with drunkard’s warts although he seldom drank. Loose flaps of skin hung beneath his brown eyes, and he had a flabby double chin. His legs were bowed and too short. His toenails were twisted and yellowish.

Occasionally, after his bath, he would sit down in the dinette and drink a glass of orange juice. A photograph of Sylvia hung there. The girl was the image of her grandmother, the very one to whom Sam did not write.

It was impossible to escape his mother. She sprang up before him over and over again in his new house. The resemblance was apparent the moment the nurse brought the newborn Sylvia to him in the Chicago hospital. Sam felt a love for this child which he knew was excessive.

Once Sylvia started to walk, she showed how capricious and contrary she would be. Sam was almost convinced that the girl was repaying him for the wrong done her grandmother.

Now Sylvia was planning to marry a Gentile, a sportsman who won medals at racing sailboats, the son of a rich engineer. She had confessed to her mother that she was living with him and had already had an abortion. Sam’s love for Sylvia was spoiled. The fortune he had amassed through the toil of a lifetime would eventually pass into the hands of this stranger who looked down at Sam from his six-foot-two-inch height with contempt.

But who else could he make his heir? The fund- raisers who came to town using threats to raise money? The American Jewish organizations, whose red-nailed secretaries clicked away at typewriters, and where directors received enormous salaries? His visits to Chicago, his reading of newspapers, and his own observations had convinced Sam Metzger that money given to charity was mainly spent to keep the organizations going. Even in his own city contributions were used to further personal ambitions. The president of the synagogue had hired his son-in-law as the architect for the new building. Another influential member had brought in a brother-in-law with a hoarse voice to be the cantor. The rabbi was also someone’s relative. They had overpaid for the site of the Jewish Center and for building materials. The son-in-law architect had designed a synagogue which resembled a bat.

This night, as on all the other nights, Sam Metzger sipped his orange juice and smoked a last cigar, though the doctor had forbidden him to smoke. Instead of losing weight, he was getting heavier. He and Bessie often quarreled about the bedroom temperature. He was always too hot and she too cold. He had high blood pressure. An artery in his left eye had burst and he had to be on medications and stick to a diet.

He was beginning to lose his hearing and had to wear a hearing aid. He had to carry two pairs of eyeglasses with him: bifocals as well as sunglasses. He constantly was switching from one to the other or misplacing them. He could find no shoes that fit him properly. Sooner or later, every pair began to pinch his feet. Somehow he was always taking medicine—for gas, constipation, headaches, stomach cramps.

In her middle age, Bessie had lost interest in Sam altogether. She lived only for her daughter, catering to her every whim. They had more than their share of problems in the business. Thefts, inefficiency, wasteful competition, and quarrels. If Sam stayed away from the business so much as a day, everything went wrong. Despite her intelligence, Bessie was a woman with devious ways and stubborn as a mule.

“Well,” he thought, “the whole thing is going to fall to pieces. Nothing will be left to show for all my hard work.”

He vaguely recalled several biblical passages from the time he attended Hebrew school in Krasnobrod, but he couldn’t remember the exact words. It all amounted to the idea that life was barren and nonsensical. A person took nothing with him to the grave but the sins he had committed against man and God.

Sam continued to sit quietly. Should he take a sleeping pill? Or should he try to get along without one tonight? He decided to take one. Nothing frightened him as much as lying awake at night, thinking. During the day, Krasnobrod and even New York were far off, but at night the years seemed to shrink. He remembered all his troubles and those of others. Sooner or later the tune “A Letter to Mama” would start running through his head.

Sam snuffed out his cigar in the remainder of the orange juice, shut off the light, and with heavy steps walked up to his bedroom. Bessie was snoring. He got into his bed and immediately felt too hot. Bessie had promised him she would turn off the radiator, but it was apparently still on. He kicked off the blanket and lay uncovered as if it were summer.

He was tired but his thoughts kept him awake. For years he had talked of retiring from the business. Were he to live to a hundred, he would have enough money. But what would he do with himself after he sold everything? Where would he live? He had already tried Miami and Santa Barbara. The idleness soon became boring. It was difficult to find a good partner at cards. He had heard a great deal about the Riviera, but how could he learn to speak French at his age?

Sam pictured his daughter, Sylvia, in bed with her Gentile, caressing him, giving herself to him. Perhaps he was talking against him, her father, and she was covering his mouth with kisses. “Well, it’s all over, all over,” Sam muttered to himself, not knowing himself what he meant by these words. Drowsy, he lay quietly, looking straight ahead, and saw at the foot of the bed a familiar form, a woman. He found himself staring at her, his mind empty of thoughts, not registering any surprise. A glow emanated from her in the dark. She stood as in a half-lit portrait. Suddenly she approached him, not walking, but drifting between him and the heavily-draped windows. He noted that instead of eyes there were two green phosphorescent lights in her sockets. When she spoke it was as if he heard her with his entire being and not with his ears alone.

“Shmulik, it’s me . . .”

At the sound of his mother’s

voice Sam’s body shuddered. He wanted to cry out, “Mama!” but could utter no

sound. At once the vision began to fade. It retreated, became dim, indistinct

and in a moment was gone altogether. The darkness

returned, and he again became aware of Bessie’s snoring. He lay motionless,

staring in amazement at the spot where the visitor had just stood. “It’s Mama,

Mama!” he muttered to himself, “She’s come to get me . . . She’s forgiven me .

. .”

He remained awake for a considerable time, waiting. Perhaps she would reappear. But she did not show herself again. He tried to recall details. How was she dressed? Was she wearing a wig or a head covering? Did she have on a skirt, a shawl? He could remember nothing. Could it have been a dream? But he knew he had been awake. He pondered the event until he was overcome with fatigue and fell asleep.

The alarm clock rang and out of one eye Sam could see Bessie getting up. Every morning she opened the store herself, not letting anyone forget that she was the owner. Now she sat on the edge of the bed, her uncombed hair a mixture of brown, red, and gray. Unkempt and haggard, she looked her very worst those first few minutes after the alarm clock rang. Her eye make-up had dried overnight and was like cracked plaster on a wall. Her forehead was wrinkled. Her lower chin sagged. Her nose seemed even more pointed than usual. Her mouth, without her teeth, was sunken and shut tight. In the semidarkness, Bessie’s black eyes, surrounded with wrinkles and dark shadows, reminded Sam of two black coals cheder boys in Krasnobrod used to set in a snowman’s head.

For a few seconds, Bessie hesitated, as if debating whether it was worth getting up or not. Then she stood up. Her body was fat and flabby while her legs were thin and varicosed. She walked unsteadily to the bathroom. Sam’s gaze followed her, but he soon shut his eyes. There was only one bathroom upstairs, and, though Bessie didn’t mind his sharing it with her, he preferred to wait till she had washed, bathed, and was out of the house before using it himself. She never ate breakfast, just drank a glass of milk.

For a moment, Sam didn’t remember what had happened to him during the night. Like every other morning, he awoke feeling insufficiently rested, with a bitter taste in his mouth which came from his bile, his liver, or perhaps from his soul. He lived in hope that the day would come when the ringing of the alarm clock wouldn’t startle him each morning, but that day was yet to come.

Now he could neither fall back asleep nor really wake up. He furrowed his brow in an effort to force himself to sleep. “What time is it, eh?” he wondered, too lazy and too indifferent to look at the clock. Surprisingly, he did doze off but soon awoke with a start. Bessie must have left the house because he heard nothing from the bathroom or kitchen.

Suddenly, remembering the apparition, Sam sat bolt upright. God in heaven! This was no ordinary morning! This was like Yom Kippur morning, where even here, in this godforsaken town, every Jew went to pray in the synagogue. There was something unusual in the air—something unidentifiably cool and heavy.

Ordinarily, Sam would fix himself a breakfast of orange juice, a roll, and coffee after Bessie’s departure, but today he had no appetite. He shaved and bathed. Standing in front of the mirror, scratching his beard, which seemed to become rougher from day to day, he came to a decision: He would go to New York, look up the Krasnobrod people, and find out the truth about his mother once and for all.

“My God, I still have relatives somewhere who most probably need me, need help,” Sam said to himself. “Maybe that’s why Mama came to me, to get me to help them. For a few thousand dollars, I might save lives!”

His conscience, which had been asleep for so many years, had awakened. “I’ll leave them enough! More than enough!” Sam spoke aloud. He was referring to Bessie and Sylvia. “She can even remarry,” ran through his mind. The painful possibility that Bessie might marry his enemy, his chief competitor, Bill Weintraub, a recent widower, occurred to him. Such things happened every day.

Sam tried to conjure up how Bessie and Weintraub would look together in the local newspaper photo above an article describing the merger of their businesses. “Maybe it’s not too late!” Sam called out, not really knowing what he was referring to. “Changing the will isn’t enough. Once I’m dead, a mere bribe can make a judge annul everything. A person has to do good deeds as long as he can stand on his feet. God Almighty has made it possible for me to fulfill this task.”

Sam Metzger dressed, packed some underwear, a sweater, and the medicines he would need. A long-forgotten energy awoke in him. The strength of a man who knows that he must act vigorously or lose everything. Bessie had left breakfast for him on the kitchen table, but he had no desire either for food or coffee. Though it was a winter day, the frost had somewhat melted. In mid-February, it smelled of spring. Sam had shaved and bathed in minutes. He went to the bank and had a part of his account transferred to a New York bank, a procedure which necessitated the signing of many papers. He told the bank official he had a chance to buy a business in New York. Sam knew full well that the news would soon spread all over town, but what did he care about small-town gossip? Let Bill Weintraub have something to think about.

Sam went into a telephone booth and called Bessie, saying, “Bessie! I’m going to New York!”

The two of them still conversed in Yiddish. Bessie was silent for a while. “What’s happened?”

“My mother died.”

“Only now? How do you know?”

“I received word.”

“So what will you do in New York? After all, she’s in Poland, not in New York.”

Bessie argued that he couldn’t leave at this time. They were getting ready for a big sale. She couldn’t be everywhere. She shouted at him in her Lithuanian dialect, calling him names. But Sam yelled back and hung up, almost saying, “Let Bill Weintraub help you!”

Aside from the special excitement he was experiencing, he felt a long-forgotten wanderlust, a boyish thrill at the thought of being free. He had bought $5,000 worth of traveler’s checks. A train was leaving for Chicago in a half an hour. He walked out of the bank and took a cab to the railroad station, arriving in enough time to have a sandwich and a cup of coffee. “What in heaven’s name led me to waste my life in this good-for-nothing hole? What was I hiding from? Where was my brain?”

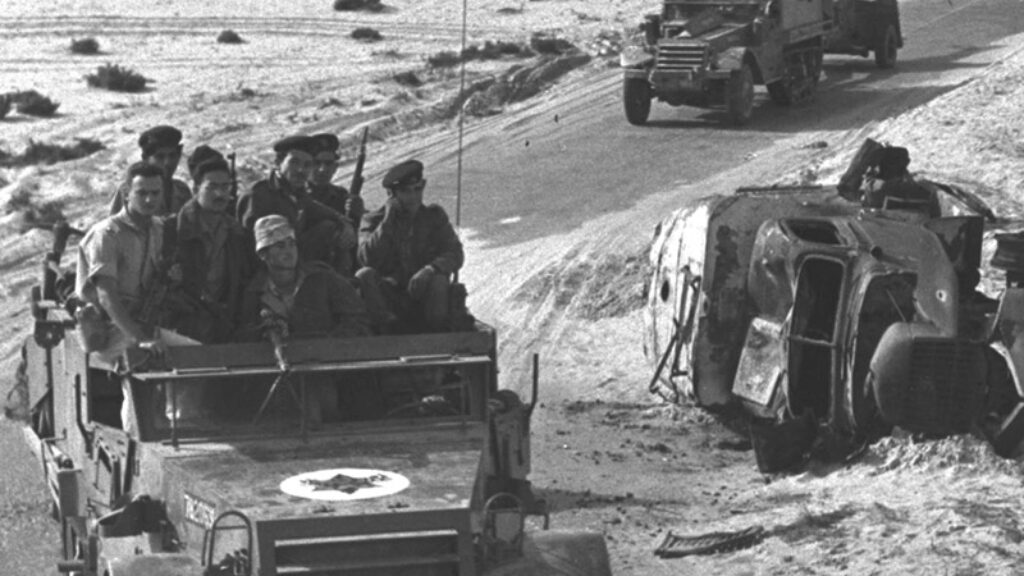

The train was warm and spacious. Sam looked out of the window at the snow-covered fields. In contrast to his lifelong habit of frugality and saving, Sam was now eager to spend money. He would go to the Krasnobrod Society in New York and donate a large sum toward relief. He would fly by plane to Poland. What could possibly happen to him? He was old and sick. He wasn’t even afraid of Hitler, who threatened Poland with war. He would travel to Krasnobrod and find his relatives there. Then he would bring them to the American consulate in Warsaw and see to it that they all obtained visas. He would rescue as many as possible.

The words of the spokesmen of the Zionist organizations, even though he had never really listened to them, now came back to mind with new force, as if he were hearing them for the first time. They repeated themselves like a record being played over and over again: “Our suffering brothers are waiting. They are our flesh and blood. If American Jewry doesn’t help, what then . . .”

“How could I have heard those pleas and remained indifferent?” Sam asked himself. True, to those delegates it was just a business. They got a percentage. But what they were saying was nevertheless true. Who would help if not he? Who should be concerned about Krasnobrod—Hitler?

Sam could hardly wait for the train to arrive in Chicago. At the station, he inquired about a flight to New York. Somehow, everything fell into place. He took a cab and drove to the airport. Ten minutes later he was airborne. “Will the plane crash? Let it,” Sam thought. He felt no fear at all, remembering a saying that those who go on a mission of mercy are protected.

The plane flew into a snowstorm and started to roll from side to side, but Sam continued to sip the cocktail the stewardess had served him. Seeing that other passengers were anxious, he smiled to himself. Next to him sat a young woman wearing a sable coat and a Russian-style fur hat, a papakha.

Sam said to her, “We’ll soon be landing in New York.”

“Either in New York or in a snowy grave,” she answered.

“Everything happens according to God’s will,” Sam said, a little surprised at his own words.

“The question is: What is God’s will?” she replied dryly.

A clever woman, Sam thought. What does God want? Who would dare go to heaven and ask God to tell him His desire?

Patches of fog drifted past the window. The pilot tried to lift the plane above the storm clouds but apparently wasn’t able to manage it. In a matter of seconds, it became dark as night outside. Sam imagined the motors were operating on their last bit of fuel. The wind was blowing against them from the Atlantic Ocean. The hostess had disappeared as if she felt personally responsible for having trapped the passengers in this dangerous situation.

The woman in the sable said to Sam, “Better fasten your safety belt.”

“What good will it do me?” Sam gestured with his hand, expressing paternal gratitude. She is more devoted than Sylvia, he thought. Sylvia, in her place, wouldn’t have given him so much as a glance.

The plane bumped down on the runway and came to a stop in the New York airport. Sam said to the woman, “Now you know what God desires.”

“Yes, now I know.”

Some men have all the luck, Sam mused. I’ve thrown away my best years struggling with that dried-up Lithuanian wife of mine, stuck in a town where everyone knows what’s cooking in everyone else’s pot.

His eyes followed the handsome woman, admiring her shapely legs. A tall man wearing a homburg greeted her. They must be aristocrats, society people, Sam decided. Perhaps he’s a diplomat.

It was already evening and the airport was brightly lit. Outdoors it was cold and foggy. The planes waiting to take off to all parts of the world looked fantastically huge. It still was impossible for Sam to comprehend how such immense and heavy structures could fly across oceans and deserts. Overnight, a machine like the one he was on could take him to Krasnobrod.

It occurred to Sam that he didn’t have a passport. He hadn’t even taken his citizenship papers with him. Carrying his suitcase, he walked through an enormous waiting room. Unlike a railway station, where the waiting passengers are warmly clad, laden with packages, the people here were wearing lightweight clothing, as if they were all flying to some mild climate. They carried small suitcases or attaché cases. It was airy and warm. Young men and women stood about in small groups, chatting casually. People here didn’t seem terribly concerned with the frightening conditions in every part of the world.

Sam went outside and took a taxi. He could tell that the cab driver was Jewish. He asked him, “Are you Jewish?”

“Sure. What else?”

“Take me where I can find some Jews.”

“New York is full of Jews.”

“Where do people from the Old Country get together? Do you by any chance know where any Jews from Krasnobrod meet?”

“Are you crazy, or are you putting on an act? Tell me where you want to go.”

“Where is the Yiddish newspaper office?”

“Mister, I’ll take you down to Second Avenue, to the Café Royal. You’ll find lots of newspaper men there.”

The driver pushed down the flag on the meter. Sam leaned his head against the side of the cab, affected by the overwhelming odor of tobacco. He rolled the window down a bit. It had been years since he was last in New York, and he hardly recognized the city. He had never really known it. The streets seemed narrower and the buildings taller. There was a hint of the nearby ocean in the air, which smelled of gasoline, exhaust fumes, and all the pungent odors of city life.

Early in the day it had been warmer, but it was turning colder now. The radio predicted a snowstorm. Sam knew that he should first have made hotel reservations, but he decided that there were plenty of hotels in New York. Now that he was here, he was anxious to be among Jews as quickly as possible. There had been a time when he had lived, worked, attended meetings in this city. He had taken up with a girl who had been a passenger on the same boat from Europe with him. He had kissed her, even planned to marry her, but through the years he had forgotten all the names and all the addresses. The girl was his age, perhaps a bit older. She was undoubtedly a grandmother by this time.

Sam shut his eyes, letting the cool wind blow across his forehead and eyelids. He inhaled the city air. He couldn’t believe he was actually making this trip.

After a long silence, the driver spoke, “You’re homesick for Jews, eh?”

Sam started. “It’s been 30 years since I’ve been here.”

“Tomorrow you can go to the Yiddish newspaper office. They’ll fill you in on everything.”

“You’ve never heard of Krasnobrod?”

“Krasnobrod? No, my dad came from a town near Minsk.”

“And your mother?”

“My mother? I don’t know. From somewhere in Russia . . . ”

The driver grumbled continuously, scolding other drivers. He blew his horn loudly at a truck which was holding up traffic and zigzagged around it, almost knocking down a pedestrian. He never stopped cursing: “Sons of bitches . . . They should break their legs.”

When the taxi drove down Second

Avenue, Sam thought he recognized the street. He saw restaurants with baskets

of rolls on the tables, store windows displaying knishes, bagels, egg kichel,

challah, apple strudel. He could almost smell the

gefilte fish, peppered chickpeas, sauerkraut, all familiar Krasnobrod dishes.

Young boys were hawking Yiddish newspapers. On a theater marquee there was

brightly lit Yiddish lettering.

Sam Metzger’s eyes filled with tears.

Jews had gone on living here while he wasted his years in exile. He could hardly wait for the taxi to come to a halt. The meter indicated $2.80, but Sam handed the driver a five dollar bill and told him to keep the change. The man was so astonished that he forgot to thank him.

Vechten Trust.)

Sam spotted the Café Royal. Around here is where I’ll stay, Sam decided. I’ll get an apartment. Let Bessie sue me for divorce. He stood on the street, staring up at the reddening sky, at the theater billboards, at the crowd that was milling around the box office. He walked into the café and heard Yiddish spoken. People were sitting at tables, shouting and apparently arguing. Sam looked for an empty table, but they were all occupied. Having come into this heated place from the cold his eyes teared up and everything appeared blurred. The room began to spin like a carousel. Gradually things came into focus. Women sat at the tables dressed like actresses, their faces thick with make-up and their eyes blue with eye-shadow, but they spoke the mother tongue. One of them, a heavyset woman, took out a jeweled lipstick case from her purse and carefully applied lipstick to her already red lips. On one finger, with a bright red nail, a stone sparkled with the colors of the rainbow. When the waiter approached her for her order, she commanded him with one word:

“Blintzes!”

Sam was on the verge of tears. Blintzes? He felt shaky, as if he were drunk. He walked up to a table at which several men were sitting and said, “Is Yiddish still spoken here? I want to hear it.”

“Where do you come from?” a big man with a red face, bulging eyes, and childlike blond curls asked him.

Sam told him.

“Maybe you’d like to buy a Yiddish book?”

“Sure.”

“Have a chair, sit down. Hey, boys, let the man sit down! That’s the way. If you’re hungry, you can order what your heart desires. What would you like? Here, you can get matzo brei any time of the year.”

“I hear you can get blintzes here.”

“As much as you can put away.”

“Can I . . . may I . . . order for everyone?”

“Move in a little closer. Fellows, who wants blintzes? Here, this is my book. It just came out in print. Poetry.”

“Poetry?”

Sam had more than once heard the word poetry but what it was he had forgotten. The man removed a yellow book with gold engraved letters from his briefcase and said, “Would you like me to autograph it? It costs twenty-five dollars.”

“Sure.”

Sam took a wallet full of bank notes from his jacket. His hands trembled. He had no five dollar bills, only ten, twenty and fifty dollar bills. He handed the man thirty dollars wanting to say something in Yiddish, but all he could muster was, “That’s for good luck . . .”

He felt an acute pang of embarrassment. Sam had never learned how to speak English properly. How often he had made a fool of himself in front of Sylvia’s friends with his bad English. And now he had half forgotten his Yiddish.

The big man with the gold-stitched tie, the author, took out a fountain pen and wrote a long inscription in the inside cover, sticking the tip of his tongue out of the corner of his mouth as he did so. The waiter arrived with the blintzes.

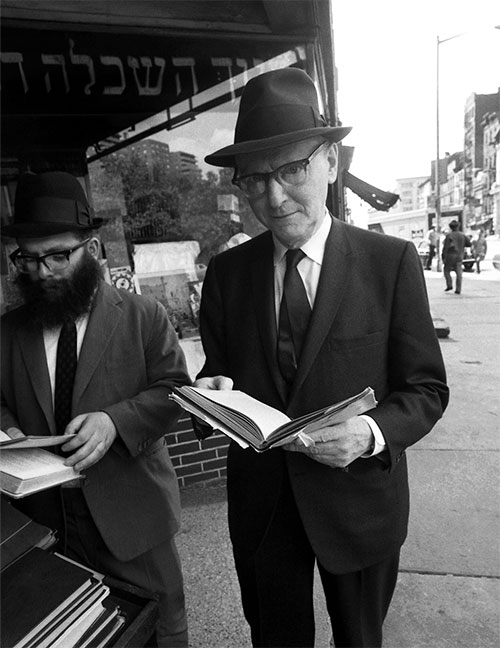

More authors with their books joined the table and Sam bought a book from each of them. He accumulated a whole pile. The writers soon resumed their interrupted debate. Though Sam understood the words, he couldn’t comprehend what these intellectuals were debating. They were accusing someone of plagiarizing entire passages from Yesenin. Who is this Yesenin? Sam wanted to ask. He opened one of the books and tried to read it, but though it was printed in Yiddish, he was unable to understand it. The words didn’t seem to go together. The lines of print danced in front of his eyes, seeming to change colors. Am I going blind? Sam thought. His throat felt dry. There was a tight feeling in his chest. He had forgotten to take his pills with him. He asked, “Do you have any idea where I can find some people from Krasnobrod?”

“Where is this Krasnobrod?”

“I’m from Krasnobrod.” Someone spoke up. It was the voice of a woman at a nearby table, the same one who had been applying the lipstick. Sam sat up.

“Are you from Krasnobrod?”

“Who are you?”

“Say, everybody, let’s push the tables together!” The big man with the blond curls called out, “It’s about time the writers and the actors’ tribe got a little closer.”

There was much gay conversation and laughter as the tables were pushed together. Sam asked, “How many years since you were in Krasnobrod?”

“Never ask a woman about years. What’s your name?”

“Sam—I mean—Shmuel Metzger. My mother, may she rest in peace, was called Belle Itte, Bracha’s daughter.”

“Was your father a butcher?”

“A butcher? No, my father died when I was a boy.”

“How did your mother manage?”

“She would go to the village to buy some buckwheat or a goose.”

“When did you come to America?”

Sam told her when.

“That’s before my time. Where did you live in Krasnobrod?”

“On the street near the hill,” Sam replied.

“Near the meat market?”

“No. The pines. What was your father’s name?” Sam asked, barely able to speak, as if afraid of what her answer might be.

“Malech Berl Altele’s son. We sold oats and flax. Where did you live?”

“Near the bridge.”

“What bridge?”

The longer the two of them spoke, the more confused both of them became. Sam mopped the perspiration from his brow. The actress rummaged through her purse and took her lipstick out again.

“Where in the world is your Krasnobrod?” she asked impatiently.

“In the Lublin region.”

“I’m from the Czernichow area.”

“Mazel tov, there are two Krasnobrods!” the big man shouted, clapping his hands together.

“Hey, waiter!”

Sam stood up. He asked where the bathroom was. He had to urinate and he had to cry.

It was late when Sam Metzger left the Café Royal with his load of books. “I didn’t know books could be so heavy,” he thought in amazement. The appetizing smells of fresh bagel and coffee came from a nearby restaurant. Newsboys were shouting the next morning headlines of the Yiddish newspapers. As he mingled with the crowd emerging from a Yiddish theater, he heard people in avid Yiddish arguing over the merits of the play. Couples strolled arm in arm, some pausing to buy a newspaper. They know how to live, Sam thought. I buried myself in some wilderness. It had been years since he and Bessie had walked arm in arm. As soon as he so much as touched her, she would protest, as if he had stepped on her foot or messed up her hairdo. She could only ridicule him and incite her daughter against him.

Sam bought a newspaper. On the front page was a headline about Palestine. “Why don’t I visit Palestine?” he asked himself. Sam paused in front of the window of a Yiddish bookstore that also sold sheet music. He would have loved to go in, but it was closed. A fine, needle-sharp snow started to fall. In a moment, the crowded street emptied except for a few drunkards who looked to him like actors on a stage set. A strong wind blew. A page of a Yiddish newspaper lifted into the air, tried to fly up to the dark red sky, fell back to earth again, spun around and came to rest at Sam’s foot. Maybe it’s a message, he thought, a letter from heaven. He wanted to stoop over and pick it up but his back wouldn’t bend. “What kinds of thoughts are filling my head,” he wondered.

A taxi drove up and Sam stepped in. Sam read the driver’s name, David Cohen, on his back license. Sam said, “Take me to a Jewish hotel, Mr. Cohen.”

“Do you want kosher food?”

“What? Yes, kosher.”

“Well, on Broadway and Fourth Street there’s a kosher hotel. Rabbis hold conventions there.”

“Okay. Take me there.”

“I once took three rabbis there. Polish refugees.”

“Have you ever heard of anyone from Krasnobrod?”

“Oh, you’ll find out about everything at this place.”

A few minutes later the cab stopped in front of a hotel. Sam went up to the registration desk and asked for a room. The clerk handed him a form to fill out and a bellhop took him up on the elevator. As they passed one floor, Sam could hear loud voices and music, and the foot stomping of a party.

He went into his room, set down his books, tipped the bellhop a dollar, and was given a key. This transaction took no more than a few minutes. He put his reading glasses on, opened one of the books, read a few of the phrases, and shut it again. “They eat blintzes like everyone else,” he thought, “but their ideas are very difficult.”

He had to use the bathroom again. Where does all this liquid come from? I don’t remember having drunk so much. He knew the truth: He had an enlarged prostate. The doctor had recommended surgery, predicting complications if it were ignored. Sam’s heart was getting weaker, not stronger.

He wanted to undress but he was too tired, so he just took off his coat and shoes, stretched out on the bed and shut the light. It was warm in the room, the steam hissed in the radiator on one monotonous plaintive note. Sam imagined that the steam was complaining, “I’m uncomfortable, I’m miserable, I can’t get out, I can’t get out. No one can help me, not even God. I must suffer, suffer . . .”

The dance music from below became louder. Sam thought he heard a familiar melody he recalled being played at Krasnobrod weddings. He wasn’t sure exactly what it was: the wedding march to the chuppah? A scissor dance? An anger dance? Sam listened intensely. This music seemed to be played by hometown musicians, magically transporting him to Krasnobrod. He saw the faces of relatives, neighbors, teachers, classmates. He pictured the rabbi with his white beard, his puffy cheeks with fine blue veins, his thick white eyebrows and heavily lined forehead. The old man smiled blissfully, a grandfatherly indulgence radiating from his eyes.

The melodies followed one after the other, and Sam knew them all. Perhaps he just imagined he did. He had heard them back home. He found himself singing along, humming the tunes. The party grew noisy. He could hear laughter, bursts of applause, loud masculine pronouncements, responsive feminine giggling. This was not a party, but a wedding. In New York, people led a Jewish life, married their children according to Jewish traditions, had Jewish in-laws.

The band stopped and then struck up again. God in heaven, they were playing “A Letter to Mama.” As soon as Sam heard this tune, his face was bathed with tears. A miracle had happened, a miracle! He had come to New York and on his very first night they had played a song that had constantly echoed in his ears. Sylvia, who had played the piano and had studied some music, had referred to this song as “junk.” But how can “junk” uplift the soul, fill it with a longing and love beyond description? Sam had the urge to go down to the wedding, to congratulate the bride and groom, to mingle with the guests. He was tired, but not sleepy. He got off the bed. His legs felt unsteady but just the same he switched on the light, found his shoes, and went out into the hall. He rang for the elevator and waited a long time, but it didn’t come.

Sam walked down the stairs, figuring that on the floor below he would find the wedding, but the corridor was dark and quiet. He walked down another flight but there was no wedding there either. For a moment he stood unbelievingly. “Is the wedding over?” he asked himself. He decided to walk down one more floor but with the same result.

He rang for the elevator again, waited and still it didn’t come. “What kind of service is this?” Sam muttered. “Well, I might as well go down to the lobby.”

He went down a few more floors without reaching the lobby. Instead he found himself in the basement. There were lights on but the place was empty. Folding chairs were stacked along the walls. Sand-filled ashtrays held cigarette stubs. Smoke was still trailing from one of the cigarettes, a sign that someone had just been there. No elevator door could be seen.

He wanted to go up to the lobby, but he needed to rest for a moment. For the past few years, he’d lived in constant fear of a heart attack. Climbing up and down stairs was too taxing for him. He was beginning to regret having gone in search of this strange wedding. Well, they must have finished their dancing. As he sat there, his mind vacant, he felt a vibration and hollowness in his knees, as if he had just climbed up, not down, all these stairs. He was suddenly overcome by all that had happened to him during the past twenty-four hours. If yesterday at this time, someone would have told him that the next day he would be in a New York hotel, searching for a wedding, sitting alone in a basement, he would have considered him mad.

He looked up and saw a pay phone. An urge to call Bessie took hold of him. She was, after all, his wife. She might be worried about him. He inserted a dime, intending to call collect, but didn’t hear the usual dial tone. The phone was apparently out of order. He clicked the receiver cradle up and down to get his coin back but nothing happened. “When men make something, you can be sure it will know how to steal,” Sam mused.

At that moment everything became dark. It seemed someone upstairs had shut the lights. Sam shouted, “Hey, you! Put the lights on! Hey, mister! Let me out!” He started to walk but couldn’t make out the exit. Like a blind man, he felt his way in the dark. He began to panic. His heart beat loudly. He could no longer remain standing. He had to sit down. His body broke into a cold sweat and severe nausea gripped him.

He felt the ground and heard the dull thud of his body against the floor. Then it became still—a stillness outside of himself as well as inside. He lay quietly, not knowing whether he had fainted or just fallen. “Is this a heart attack?” he asked himself. If so, it isn’t so terrible. It’s probably gas, from the blintzes.

A sense of peace descended upon him. He shut his eyes. He listened to his innermost self. His desires, his regrets, left him. He knew now that Bessie would marry Bill Weintraub, yet he felt no anger toward them. What’s the poor woman to do?

His mother reappeared, but something had changed. She and Sylvia were one and the same woman. “How come I didn’t understand this before?” he asked himself.

He became light and started to fly into the night. He flew past the New York skyscrapers. Together with his mother he flew over a congealed ocean. Down below, ships stood motionless. Then mother and son approached a path between two mountains. In the valley, he saw something shining like a brilliant red sunrise. Where is my father? he asked himself and heard the answer, “You, Sam, are your own father.”

At the border, an unseen power held him back, but his mother embraced him. Together, arm in arm, they floated back to Krasnobrod.

Translated from the Yiddish by Aliza Shevrin. Copyright © 2019 Isaac Bashevis Singer Literary Trust LLC. All rights reserved.

Suggested Reading

Looking Backward and Forward

Response #2: David Biale revisits his provocative 1998 essay on Jewish assimilation.

Context and Content

How can Zionism’s biggest critics know so little about its history?

As the Story Goes: Hanukkah Spears, Cheese, and Goblins

Where did all the Hanukkah stories go?

History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

On-screen, Mel Brooks was hysterically funny. Off-screen, he could quickly shift to morose or mean.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In