In Pursuit of Wholeness: The Book of Ruth in Modern Literature

While not the most dramatic of all the biblical stories, the quietly moving book of Ruth, which we read on Shavuot, continues to resonate in Western literature. Sometimes the references are explicit, as when John Keats famously wrote, “Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home / She stood in tears amid the alien corn.” Yet we also encounter Ruth-like scenarios that draw on, or even undermine, the book’s central theme of chesed, or loving-kindness.

American novelist Marilynne Robinson and Israeli writer Meir Shalev invoke the Ruth story to tell biblically infused stories that expressly do not end in redemption. In contrast, S. Y. Agnon found a way to draw upon it while keeping the transformative spirit of the biblical narrative.

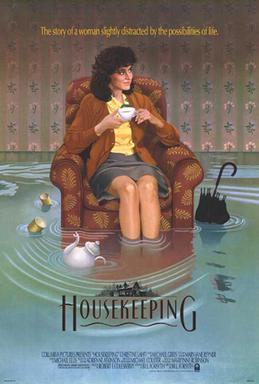

Robinson’s Housekeeping is the story of a young girl named Ruth who, along with her sister, Lucille, is abandoned by her mother and left with a chain of relatives, finally ending up in the care of her eccentric aunt Sylvie. This aunt and the two girls have all been abandoned by their closest relatives, and they try to create a home for themselves. As is often the case in Robinson’s fiction, explicit echoes of the Bible are everywhere:

Cain murdered Abel, and blood cried out from the earth; the house fell on Job’s children, and a voice was induced or provoked into speaking from a whirlwind; and Rachel mourned for her children; and King David for Absalom. The force behind the movement of time is a mourning that will not be comforted. That is why the first event is known to have been an expulsion, and the last is hoped to be a reconciliation and return.

Here the character Ruth considers the many places in the Hebrew Bible where a loss of family and pursuit of restoration propels the narrative forward. Robinson’s Ruth is similar to the biblical Ruth in her fierce loyalty to her aunt, in contrast to Lucille, who, like Orpah, ultimately rejects both of them in favor of a more conventional existence. In the Bible, Ruth achieves a stunning level of success in restoring Naomi’s family through her union with Boaz, redeeming their family name and helping to forge the destiny of the nation of Israel.

Restoration is far more elusive in Robinson’s novel. The home that Sylvie builds for herself and Ruth is provisional. Whereas Ruth gleans in foreign fields out of necessity for Naomi and herself, Sylvie and Ruth are drawn to the trappings of an itinerant lifestyle out of some kind of unfulfilled inner need. Whereas in the Bible, Naomi seeks a home for Ruth—“Daughter, I must seek a home for you, where you may be happy” (Ruth 3:1)—Sylvie believes that Ruth’s happiness lies with Sylvie and in the temporary home they fashion together. At times it feels as if Robinson is imagining what would have happened if Ruth had never had the luck of running into Boaz the redeemer and instead had stayed together with Naomi and fashioned a life together, away from the busybodies of Bethlehem.

Yet Sylvie and Ruth pay a great price for their excommunication from polite society: In contrast to the great genealogy following the book of Ruth, they will be forgotten. Early on in the novel, Ruth meditates on the wife of the biblical Noah and wonders whatever happened to her: “She was a nameless woman, and so at home among all those who were never found and never missed, who were uncommemorated, whose deaths were not remarked, nor their begettings.”

Robinson’s Ruth finds herself entering this sisterhood of nameless women, as she and Sylvie quietly slip out of their hometown into an anonymous vagrancy that provides some solace as well as a lingering sense of incompleteness. This, in a way, is a Ruth that could have been, one whose life throws the nobility of Boaz and the serendipity of the biblical account into even greater relief.

This anxiety about genealogy—and about being forgotten—colors another great novel in dialogue with the book of Ruth, Two She-Bears (Shetayim Dubim), published in Hebrew by Israeli writer Meir Shalev and deftly translated into English by Stuart Schoffman (my fellow columnist here at JRB). Shalev has written the story of two Ruths. One, Ruth Tavori, endures a difficult marriage in British Mandatory Palestine. The second, her granddaughter Ruth, called Ruta, is a high-school Bible teacher in the Yishuv her grandparents helped build.

The connections with the biblical book of Ruth are both explicit and implicit, as the narrator writes of the younger Ruth:

She was called Ruth Tavori in proper Hebrew: Rut Tavori, with a dignified pause in between, like at a state ceremony. But if you say the name without a proper space it comes out sounding “Ruta Vori.” Try it, Varda, say it out loud. You see? Just like Ruth the Moabite. You pronounce it formally, she’s the great-grandmother of King David—but “Rutamoaviah” is the one who spent the night with Boaz on the threshing floor.

As figures who are involved in building the State of Israel, the elder Tavoris live their lives in a biblical key. The narrator asks, “Who wasn’t a woman of valor in the history of the Yishuv?” Yet the characters break under the burdens they carry—their sense that they are participating in something of great historical importance contrasts with the dissolution of their private lives and relationships. (“You hear that, Grandma Ruth? You were a woman of valor even if you cried for no reason.”)

The novel contains some explicit parallels with the book of Ruth—two strong women, “she-bears,” who endure huge losses and strive to move on amid a pastoral agricultural landscape in the Land of Israel. However, the book of Ruth also reminds us of the characters’ limitations, particularly in the realm of reproduction. Early on in the novel, the narrator reflects the following:

As you may or may not know, history in the Bible is inseparable from genealogy, all those long lists of people who begat and begat and begat, this one begat that one who begat that one who begat that one, because that is what’s really important and not all the Zionist slogans about coming to the Land of Israel and founding a village and forming committees and plowing the first furrow—what’s really important are names, births, deaths.

We will soon learn that the house of Tavori is plagued from its inception by a certain impotence, both literal and figurative, and all of the characters need to make a kind of peace with the question of what will endure after them. One child dies from snakebite; another is cruelly murdered only a week after she’s born. There is a sense that this family has removed itself from the biblical train of who “begat” whom, and the connections with the biblical Ruth remain ironic at best.

The book of Ruth, a midrash tells us, was written only “to teach how much reward comes to those who act with loving-kindness” (Ruth Rabba 2:14). In the hardscrabble world in which Marilynne Robinson’s Ruth resides, Christian neighbors can at best offer a bland and conventional kind of assistance, and, once they recognize the depth of Sylvie’s unconventionality, the neighbors’ interest in the protagonists is weaponized against them. In Two She-Bears, the patriarch of the family, Zev Tavori, does not possess the humility of the biblical Boaz. Whereas Boaz essentially effaces himself by enabling a variation of the biblical idea of yibum, the continuation of the family line by the deceased husband’s brother, Tavori turns to murder.

One novelist willing to explore the unique quality of chesed that is at the heart of the book of Ruth is S. Y. Agnon. In his short story “In the Prime of Her Life,” first published in 1923, Agnon touches on key themes of the Ruth story, particularly the concept of yibum and how it might play out in the context of a bereaved family. It is narrated by a young woman named Tirza, whose own mother, Leah, died “in the prime of her life” (age 31) of a “heart illness” (machalat halev).

Tirza is consumed with thoughts of a sensitive poet and teacher named Akaviah Mazal, who once loved her mother and whom her mother loved in turn. Tirza’s mother was barred from marrying Akaviah for economic reasons, and, after her death, Tirza finds a journal written by Akaviah that includes his reflections on his love for Leah. Tirza writes, “And in those days I read from the Books of Joshua and Judges, and at that time I found a book among my mother’s books, may she rest in peace.” The book of Ruth opens with “in those days of the Judges,” and thus Agnon subtly clues in the reader to the connection between the story of Leah and the book of Ruth.

As Tirza broods upon the loss of her mother, she increasingly feels a kinship with Akaviah, with whom her mother had had such a strong connection. Tirza attends a school for teachers where Akaviah is employed, even though she is ill suited to teaching, and clandestinely approaches him one evening, in a way that also reminds us of Ruth. She learns from Akaviah that he was born to a family of converts, once again bringing to mind Ruth as the prototypical convert, though in Akaviah’s case, his family had begrudgingly converted to Christianity for economic reasons.

Akaviah’s mother had sought to return to the Jewish people, and Akaviah continues this trajectory:

He had yearned with all his heart to complete what his mother had set out to accomplish upon returning to the God of Israel, for he had returned to his people. Yet they did not understand him. He walked as a stranger in their midst—they drew him close, but when he was as one of them they divided their hearts from him.

While Agnon invokes several of the ingredients of the book of Ruth, he does not employ them in some mechanical one-to-one fashion. Tirza reminds us of Ruth in some ways, but Akaviah is also a Ruth-like or perhaps Naomi-like figure in his outsider status among the Jewish community to which he has returned. Even in the Ruth story itself, some of this inversion of roles exists. When Ruth prostrates before Boaz in his Bethlehem field, she thanks him for his kindness to a foreigner. Yet when she comes before him in the middle of the night, it is he who thanks her: “Be blessed of the Lord, daughter! Your latest deed of kindness (chesed) is greater than the first, in that you have not turned to younger men, whether poor or rich” (Ruth 3:10). Chesed does not flow in one direction in the book of Ruth—Ruth and Boaz each provide chesed and are recipients in turn, thus collapsing the hierarchy between them. Tirza longs for Akaviah and for the family restoration that he can provide. Akaviah urges Tirza to pursue a man who is younger and more appropriate for her, but she refuses. Ultimately, the story suggests, in the spirit of yibum, that past wrongs can be redeemed and a broken family can be mended through the unrelenting dedication of one young woman.

“In the Prime of Her Life” concludes with an idyllic though subtly discomfiting scene in which Tirza is married to Akaviah and pregnant with their first child. Akaviah had warned Tirza before their marriage that she is still young and that he had “come to the age where all I desire is some peace and quiet.” His hesitation, as well as the reservations of those around her, do not deter Tirza, and she pursues this unlikely union faithfully even if it is not the romance for which other girls her age may hope.

Their newlywed bliss is soon punctured by misgivings—Akaviah is busy writing a history of the Jews of their town, and Tirza finds herself resentful of her domestic duties and lonely. Nevertheless, the rooms of the newlywed couple are “suffused with warmth and light,” and Tirza is heartened by the close relationship that grows between her husband and her father, who visits them each evening.

Tirza’s life with Akaviah is far from perfect, but she senses, as does the reader, that her unconventional choice is imbued with larger significance. Tirza’s father and Akaviah should be at odds with one another as former rivals. Yet Tirza’s marriage to Akaviah unifies the two men and closes a circle. Toward the end of the story, she gazes upon her husband and father:

Now I glance at my father’s face and now at my husband’s. I behold the two men and long to cry, to cry in my mother’s bosom. Has my husband’s sullen mood brought this about, or does a spirit dwell in womankind? My father and my husband sit at the table, their faces shining upon me. By dint of their love and compassion, each resembles the other. Evil has seventy faces and love has but one face.

This sentiment, “evil has seventy faces and love has but one face,” evokes the spirit of yibum, through which one husband can virtually morph into another and in which chesed makes family restoration possible even after tragic loss. This is part of the triumph of Megillat Ruth—Ruth the Moabite, whose ancestor Lot was once banished from Abraham’s tent, now returns to the Jewish people. The family line of Elimelech and Naomi, once threatened with dissolution, is also symbolically maintained through the union of Ruth and Boaz. Agnon brings the unlikely chesed of Ruth to life that suppresses none of the strangeness of the not-quite-yibum predicament.

Modern novels often explore the dissolution of families and relationships. The book of Ruth, too, presents an account of familial dissolution, but it is followed by restoration. Agnon’s invocation of the book, notwithstanding its irony, is a rare example of a modern work that mines the biblical story in its full depth. Ruth’s travails alongside Naomi, their exile, and their exclusion from civilized society are a natural fit for modern novelists like Robinson and Shalev. Both of these modern stories are infused with a hint of the same eternal quality. The inexplicable acts of goodness that drive men and women like Boaz, Naomi, and Ruth are harder to find, in literature and in life.

This article is adapted from Sarah Rindner’s contribution to Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth.

Suggested Reading

Shouts and Roars for the Finalists

Five finalists for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature have been announced. Read our reviews now.

Rereading Herzl’s Old-New Land

A bad novel, but an important and prescient book.

Unspun

I reserve the right to chat with you about all of my reading, whether there be dragons or not.

Shylock at the Barricades

The new production of The Merchant of Venice is both revolutionary and timely. It’s also deeply disappointing.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In