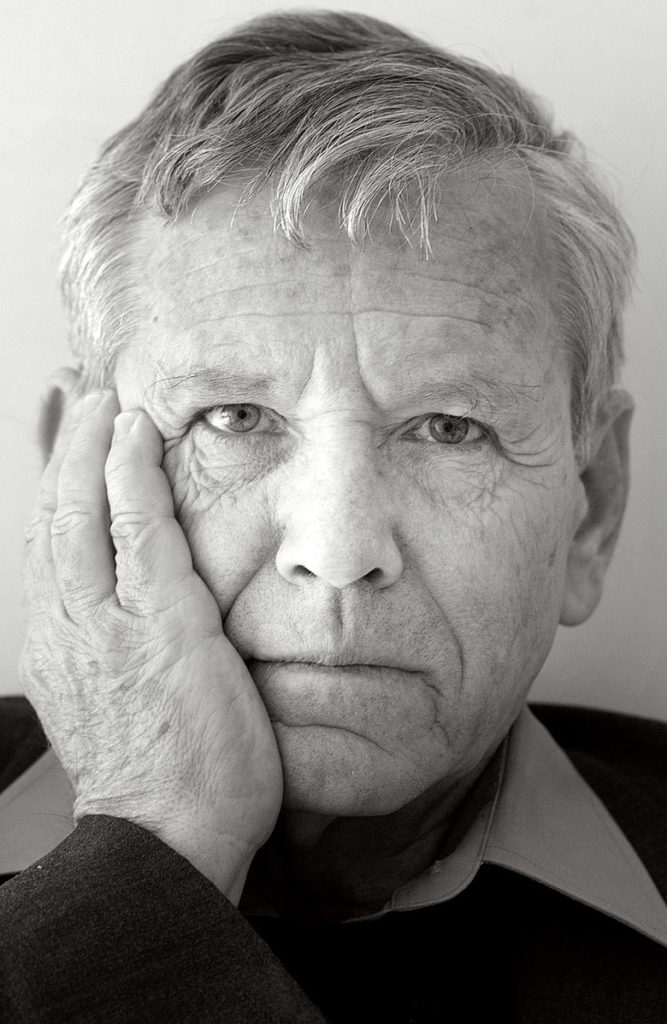

Agnon, Oz, and Me

Over the years, I’ve spoken privately with several Israeli novelists but with only two of the internationally famous ones. And these very brief conversations took place more than 40 years apart from one another.

After I graduated from high school in June of 1967, and after the I.D.F. completed its more important business during the same month, I spent the summer in Israel as a participant in a program put together by the very short-lived World Jewish Fellowship. The best part of it was our three-week stay in Jerusalem, during which the dozen or so American participants lived with Israeli families that had at least one high-school-aged, English-speaking child. We all hung out together, doing things serious and frivolous, and later traveled throughout Israel together in the same pickup truck.

One day in July or August, I went looking for the Israeli “brother” of one of the other participants, who lived in the same apartment building as I did on Washington Street, within sight of the YMCA. When an elderly man I did not recognize opened the door for me, I asked him if Gad was home. He affirmed that he was, so I headed down the hall to his room.

“Your grandfather looks a lot like him,” I told Gad Yaron, as I pointed to the big poster on his wall, which reproduced a photograph of Shmuel Yosef Agnon, who had won the Nobel Prize in Literature the previous year. “What, seriously?!” Gad replied, mostly befuddled by my observation, but a tad contemptuously. “You didn’t know?” No, nobody had told me that his mother was Agnon’s daughter.

“Do you want to meet him?” Gad asked. Of course, I did. I had read a couple of his stories in a class at Camp Ramah and didn’t particularly like them, but he was, after all, famous, and talking to him would, therefore, be an experience—just the kind of thing I was collecting.

We went back out to the living room, where Gad introduced me to his then 80-year-old grandfather as a friend from the United States.

“Baruch ha-ba. Where are you from?”

“New York,” I said, to keep it simple.

“What part of New York?”

“Not New York City,” I explained, assuming that that was what he had in mind, “but a small city north of it, Albany. It’s the capital of New York State.”

Somehow, this aroused the curiosity of the great author. He—or maybe Gad—pulled down a volume of a Hebrew encyclopedia that was right there, on easily reachable shelves, and the information I had provided was soon verified. Agnon also asked me how many Jews lived in Albany. I remember nothing else of our conversation and was never face to face with him again.

On Sunday, November 15, 2009, I went to Brandeis University to hear Amos Oz talk about his quite excellent book, A Tale of Love and Darkness. After he said a few things about the problems he had encountered in producing an English translation of it, I had to ask a question. Not too long beforehand, I told him (and the rest of the audience), that I had wanted to show a particular passage to a non-Hebrew-speaking friend and had been surprised not to find it in the translation. It was, I said, part of his wonderful description of his family’s Sabbath stroll across Jerusalem around in the early 1950s to have lunch at the home of his famous great-uncle, Professor Joseph Klausner of the Hebrew University, together with his guest Benzion Netanyahu and his two then quite small sons, Jonathan and Benjamin.

Oz interrupted me at this point and smilingly explained that the omission was due to the publisher, who wanted to shorten the volume wherever possible. And then he proceeded to repeat the story, to which I was referring, of how he had once been sitting at that very lunch table and felt someone tugging on his shoelaces. So he gave the future prime minister a good kick!

This got a laugh from the crowd—but it wasn’t the way he told the story in the book. I’ll translate:

Among the guests at Klausner’s house were “Dr. Benzion Netanyahu and his little boys, one of whom, when I was around bar mitzvah age, I kicked with a full sweep of my shoe, because he was crawling under the table, untying my shoelaces, and pulling on my pant legs (to this day I don’t know whether I kicked the heroic brother [ha-ben ha-gibor] or the nimble brother [ha-ben ha-zariz]).”

I still wasn’t satisfied by Oz’s explanation of the missing passage. It didn’t dispel my suspicion that he might have had some other reason for leaving out the (as some English-speaking readers might have perceived it) offending words. And I was of course surprised by the new twist in the story. But there were a lot of people who had their own questions, and I didn’t get to ask a follow-up.

On Monday, I returned to Princeton University (where I had a fellowship that year). The next day I had to attend a meeting in New York City and chose to go by train. After parking my car, I entered the station at Princeton Junction and was struck immediately by the sight, 20 feet away from me, of none other than Amos Oz sitting on a bench, waiting for a train with a woman who could only have been his wife. Now, I’ve been trained by my wife to leave celebrities alone, and I’m usually pretty good about it, especially when they look as delighted to be alone together as the Ozes did, but this time I couldn’t restrain myself.

Their presence wasn’t a mystery. They were visiting their daughter, who also had a fellowship at Princeton that year, and they were on their way into the city for the day. And I could tell, pretty quickly, though they were polite enough, that they didn’t really want any company. But I couldn’t make myself go away. In my defense, though, I can say two things: I refrained from pushing for a further response to my still unanswered questions about the sentences that got lost in translation and asked instead about some other things, and I didn’t try to sit near the Ozes on the train.

By the time they arrived in New York, no doubt, their memory of my intrusion had already blended together with their recollections of the innumerable other fans and cranks who had violated their privacy over the years. My own regrets didn’t dissolve that quickly, but one thing that helped was something I subsequently read—or rather, reread after having forgotten it—in A Tale of Love and Darkness. Early in the book, Oz tells the story of his own first, postchildhood meeting with Agnon (who had once been on friendly terms with his parents).

When he was a 20-something student of literature at Hebrew University, Oz went to Agnon’s house in Talpiot and rang the doorbell. “Agnon’s not in the house,” Mrs. Agnon told him, with angry politeness, hoping to chase away another one of the nudniks who were always trying to steal her husband’s time. She had told the truth but not the whole truth, for Agnon just then emerged from the adjacent garden and began questioning Oz somewhat suspiciously. But once he understood whose son he was and had heard a bit of his story, he invited him into his house to talk for a while.

Agnon was evidently and justifiably a lot more curious about Oz than he was about me a decade later, but after about a quarter of an hour he was, Oz tells us, visibly impatient and clearly looking for a way to get rid of his visitor. That’s when Oz gathered his courage and told him why he had come. It wasn’t his reasons for coming that mattered to me—they had to do with his own literary aspirations—but the fact that he didn’t go away when he knew he wasn’t wanted. Somehow, it made my behavior a half-century later seem less egregious. But I was still glad that I had at least headed for a different car when the New York-bound train pulled into Princeton Junction.

Suggested Reading

What’s Going On With Antisemitism?

Jonathan Karp responds to Reviel Netz

Fathers & Sons

This summer, as the current Askhenazi chief rabbi was being investigated for corruption, and issues of religion and state dominated public debate, new Ashkenazi and Sephardi chief rabbis were elected. The process was messy, complicated, and ugly. The result? Sixty-eight votes apiece for the sons of two previous chief rabbis. What does a broken rabbinate mean for Israel?

Workday Jews

In their respective books, Chad Alan Goldberg and Eliyahu Stern address the question of whether the Jews are the quintessentially modern people or a people who came to modernity late and with a sudden shock. They reach very different conclusions.

Jocasta Speaks

The Jewish woman, before feminism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In