The Fix Was In

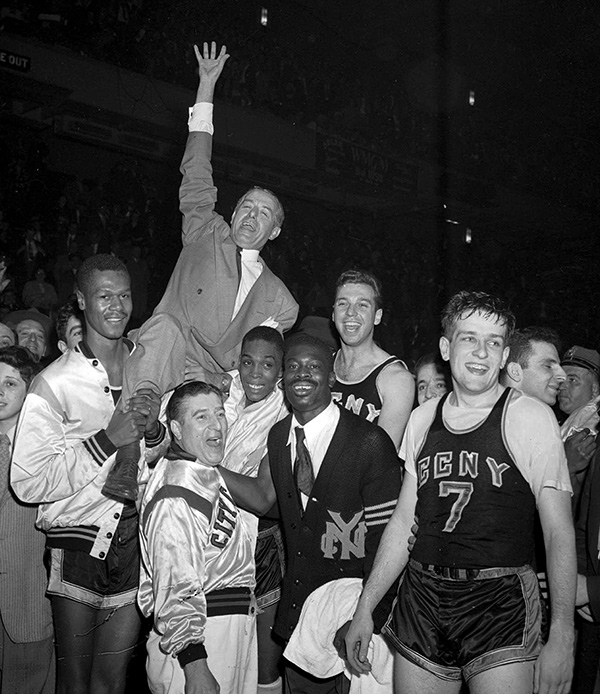

Forget the Giants/Dodgers one-game playoff that ended with Bobby Thomson’s ninth-inning homer, the “shot heard around the world,” in 1951. Forget the Max Schmeling/ Joe Louis heavyweight rematch in Yankee Stadium in 1938, in which a black American dismantled the Nazi myth. Forget the perfect game thrown by the Yankees’ Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series. The high point of midcentury Gotham sporting life came in the spring of 1950, when the City College of New York Beavers basketball team, with a starting lineup consisting of three Jews and two blacks, wiped the floor with the top-ranked Kentucky Wildcats en route to the NIT championship in Madison Square Garden.

Final score: CCNY 89, Kentucky 50.

It was not just the manner of victory, the fact that CCNY was a team with a revolutionary style characterized by the fast break, which reflected the speed and panache of the city playgrounds. Nor was it the David-versus-Goliath nature of the triumph, the fact that CCNY, a tuition-free refuge for ethnic overachievers who’d been quota-ed out of the Ivy League, had taken down the basketball elite. It was that this game, coming at a time when being black or Jewish was exactly the wrong thing to be, seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

Kentucky was coached by a legendary coach named Adolph Rupp, who had never rostered blacks and didn’t like to play against schools that did. As for Jews, it’s like my father said when I asked if he’d faced antisemitism when he moved to Libertyville, Illinois. “They didn’t even know what we were.” But Rupp had no choice. If he wanted to win the NIT tournament, then more prestigious than the NCAA, he had to beat CCNY, which was in the midst of perhaps the greatest season in college basketball history—it ended with a “grand slam,” that is, championships in both the NCAA and NIT tournaments.

The telling moment came before the game even started. “As referee Jocko Collins prepared for the opening toss, the City College players extended their hands to their Kentucky counterparts,” Matthew Goodman writes in his terrific new book The City Game: Triumph, Scandal, and a Legendary Basketball Team. “The pregame handshake was a standard ritual, a simple gesture of courtesy and sportsmanship, but this time was very different: This time three of the Wildcats turned away. . . . It was as though a lightning bolt, brief and unexpected and frightening, had pierced the arena.”

I’ve heard stories about this game, this team, and these players all my life. Though I grew up in the sticks, my father is from Brooklyn (if you’d asked me, at age 10, what my father did for a living, I’d have said, “He’s from Brooklyn”). Goodman’s book adds detail to the stories my father told and explains what happened before and after, but the essentials remain the same. This is playground lore, the world as it was seen from Gravesend Bay in the 1940s and 50s, when some of the city’s best basketball was being played at the Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, where my father saw a 17-year-old Sandy Koufax, a member of the J’s all-star team, dunk over the center of the New York Knicks in a charity game. To my father, and probably to Koufax, too, CCNY’s defeat of Kentucky was an event of near historical importance. He knew every player on that team, even the subs, and described them as Homer described the crews of Athenian warships. Ed Warner, a six-foot-four power forward from DeWitt Clinton High, “smooth as silk, hard as glass.” Floyd Lane. Irwin Dambrot. Ed Roman, the Hebrew behemoth, who’d played high school ball at William Taft in the Bronx. “Roman was the most dominating force in the game.” There was one player from Lafayette High School, my father’s alma mater, named Norm Mager, a six-foot-five forward, who “if he was now like he was then could start on any team in the NBA,” and two players from rival Erasmus High, Alvin Roth and Herb Cohen.

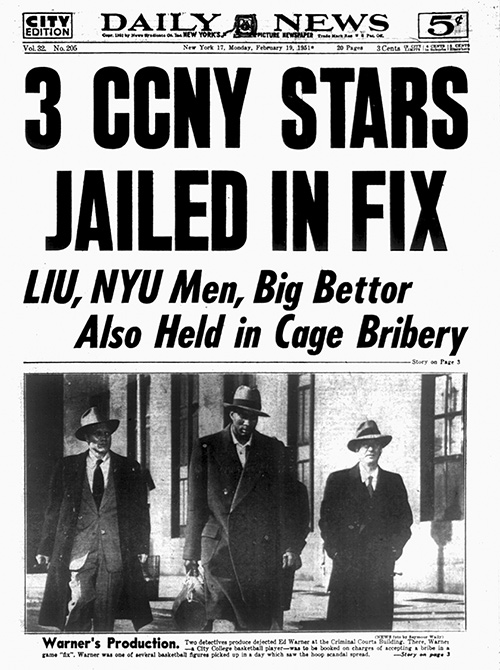

The fact that several of these players had been corrupted by bookies and gamblers; the fact that, even as they went through that magical 1949–1950 season, they were being investigated by undercover cops; the fact that they’d taken money to shave points, to win but not cover the spread, would not diminish their achievement, but merely complicate and darken it. The revelations made the CCNY Beavers something more than a newspaper story—this was literature, human nature, life. You thought you knew what it meant, but it turned out to mean something else too. “Even Fats Roth dumped,” my father would say.

Goodman, whose previous books include Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race around the World, spent years researching The City Game, and the result is a sports-writing masterpiece. Although sports writing is banished to a ghetto-like section in stores and libraries, it can give you everything. All the emotions people hide in normal life are exposed on the fields and the courts of the world. That’s why so much of the best literature has been a variety of sports writing. Hemingway’s war stories are really sports writing another way (as he knew)—ditto, I’d argue, the stories of James Salter and Hunter S. Thompson, not to speak of Tolstoy.

In The City Game, Goodman has found a cast of characters as rich as any novel’s, starting with coach Nat Holman, who took the CCNY job with a mission in mind: He’d not only build a quality program but use it to show that the castoff refuse of Gotham could compete with anyone. The big schools, the state universities that had money and recruiting tools, had become the dominant powers in the game. These are schools we still associate with basketball: Kentucky, Syracuse, Ohio State. Standout players came from prep schools where boys were taught to shun excesses of style and personality. Holman wanted to work in tougher clay, which he knew he’d find in New York’s outer boroughs, where veins of talent went unrecognized.

Basketball had been invented by James Naismith in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891 to keep kids in shape during the winter, and in the 1920s, Nat Holman had been its first great star. Growing up in a tenement on Norfolk Street in Manhattan, Holman learned the game on the Lower East Side, “playing one-on-one against other neighborhood kids in Seward Park playground for a nickel or a dime or sometimes an ice-cream cone,” Goodman writes. “From 1921 through 1929, he was the featured player for the Original Celtics, a touring team, that over the course of Holman’s career compiled a staggering record of 720 wins against only 75 losses.”

He was a (Jewish) prince of American sport, an ambassador no less than Connie Mack or George Halas. Holman’s picture had even been on a Wheaties box. He was also, as Goodman shows, kind of a jerk. As such, he tended to stay above the nitty-gritty, which was farmed out to his assistant, Bobby Sand, who did everything for Holman—scouted and recruited kids, ran practices, drew up plays. According to Goodman, Bobby Sand was the real author of Holman’s book, Scientific Basketball.

“Sand had heavy eyebrows and a round face like a fellow City College graduate, Edward G. Robinson,” Goodman writes. “He had a perpetual five o’clock shadow (he had begun shaving even before his bar mitzvah), and his clothes, no matter how new or recently ironed, always seemed rumpled. At five foot seven, he was shorter than the young men he coached and stockier, and his voice was redolent of his Brooklyn upbringing, in which the game they played was ‘bask-uh-ball.’” And he was a genius: “He was fluent in five [languages] and could read four more.” After playing on the 1937–1938 team nicknamed the Mighty Midgets, Sand got a doctorate in economics from Columbia; he later taught at City College. He had a sickly wife and infant daughter and was stretched very thin, but Goodman portrays a man obsessed with basketball:

At home, eating an orange, he’d move pits and pieces of peel around on the counter, lost in thought: he was working out long progressions of moves, imagining the opponents’ responses for each and the most effective counterresponse in turn, like a chess player trying to read the future from the position of the board.

It was Sand who sold Holman on the fast break, an innovation the head coach at first dismissed as unsound. Until then, basketball tended to move at a stately pace. Absent the shot clock, which was not introduced in college until the 1980s, players would pass the ball around for a minute or more, in search of a perfect opportunity, which might be a “two-handed set shot in which the ball was pushed from chest level,” Goodman writes.

Holman’s brand of basketball, which would vanish within a decade, was terrestrial, with both feet set firmly on the polished maple floor. Sand convinced Holman that CCNY had to innovate to compete at the top level, which meant the fast break, wherein a team transitioned from defense to offense in a flash, moving the ball downcourt via a few long passes, a sequence culminating in a layup or dunk. Sand found kids who could play this style in New York’s public schools.

New York was a capital of hoops back then, with over a half dozen top college teams (CCNY, Long Island University, Brooklyn College, NYU, Iona, Manhattan College, Columbia, St. John’s) playing in the metro area. But CCNY was the best of those teams, so its players became heroes, extolled in the newspapers. Most home games were played at the old Madison Square Garden, where the seats climbed to the rafters, the men wore suits and hats, bookies bantered with gamblers in the aisles, and a thick impasto of cigarette and cigar smoke collected along the ceiling. (“One prominent head coach, Frank Keaney of Rhode Island State, would light smudgepots in the college gym during practices to prepare his teams for [the Garden],” Goodman writes.) Few people left before the final buzzer, even when the game wasn’t close. According to Goodman, this was less because spectators loved the sport than because many had bet the spread and were waiting to see if CCNY would cover, hence the huge cheer that might follow a seemingly meaningless free throw.

And that’s how the worm got into the apple. All that money, so much being made by promoters, vendors, coaches, and schools—that is, by everyone but the players, many of whom came from lower-middle-class or poor families. You’d see them, according to Goodman, in the street before games, “coats thrown on over warm-up suits,” scalping their complimentary tickets; it might mean as much as five or ten dollars cash. To bookies and gamblers like Salvatore Sollazzo, this represented an opportunity. The world of college sports was corrupt; it seems inevitable that that corruption would infect student athletes as well.

In the summer, many top college players worked as waiters in the Catskills—the Hotel Brickman, Young’s Gap Hotel, Klein’s Hillside Hotel, Kutsher’s Hotel and Country Club, the Ambassador Hotel, which “dispensed with individual recruiting and just imported the entire Bradley starting five from Peoria.” Of course, their real job was basketball. They were ringers, brought in to play in the local league and entertain the guests (Wilt Chamberlain had a gig like this at Kutsher’s a few years later). Of course, bookies and gamblers need to get away too, so that’s how the connections were made: I’m not asking you to lose, kid; just don’t win by so much.

A strength of Goodman’s book is the way it conjures the lost worlds of New York. The Catskills, aka the Jewish Alps; the tenements, with their Yiddish-filled hallways and starch-heavy meals, “brisket and roast chicken, and potato latkes, and stuffed cabbage and kugel, washed down with glasses of seltzer and cherry soda”; the Harlem streets, where the numbers game was a neighborhood obsession; the playgrounds, where everyone played basketball because basketball required little space and just one ball, making it the most democratic game. The book draws landscapes but also people, a series of profiles, a dozen stories of rise and fall, of how a childhood passion—hoops—turned first into a shot at college, then into stardom, then into criminality and shame. For the 1949–1950 CCNY standouts, whom Goodman follows into middle age and even dotage, the point-shaving scandal amounted to 24 months that netted little cash—they were paid around $1,000 for each adulterated contest—but haunted the rest of their lives.

Goodman tells the story of the team but also the story of the cops, detectives, prosecutors, and politicians who profited from or uncovered the fix. The US attorney’s investigation into illegal gambling—it went far beyond basketball—would entangle big fish, including New York mayor Bill O’Dwyer. In the end, 13 college players were indicted, including “six from Long Island University, four from City College, two from Manhattan College, and one from New York University.” But City College got the headlines because City College was the best team in the country, as well as a symbol of the city itself. Most of the Beaver players ended up with suspended sentences, but point guard Alvin “Fats” Roth and tournament MVP Ed Warner were sentenced to six months in jail. As Goodman shows, the judge seemed inclined to be harsh with these two not because they were more culpable but because they weren’t good students, citing Roth’s faked transcript (Coach Holman’s handiwork) and Warner’s low IQ scores. Roth’s mother was seriously ill, and he was granted an extension of bail to visit her. Eventually, a deal was worked out for him to join the army rather than going to jail. Warner, who was black, went directly to Rikers Island. Warner surely could have played in the NBA, but he was permanently banned by the league, though he and several other players did end up playing in the minor league Eastern Basketball Association.

Along the way, the book illustrates several hard truths about the world and the way it works. Take St. John’s, which was a dominant basketball power in the 1950s. St. John’s players, who were likewise corrupted, were let go soon after their arrests and never charged. Why?

According to Goodman, it had to do with the relationship between the US Attorney Frank Hogan, “an observant Catholic,” and New York’s Cardinal Spellman. “The story I got was that Hogan wanted to run for governor,” sportswriter Jerry Izenberg said later. “Spellman called Hogan and said, ‘You know, I can get you every big Catholic donor. Period. But that team is not to be touched.’” The account of basketball writer Charley Rosen, who spoke with numerous players and coaches of the time, differs slightly, Goodman goes on. “According to Rosen, ‘Spellman sent a Catholic detective to Hogan to [pass] the word to lay off the Catholic schools. They couldn’t risk a face-to-face meeting, or even a phone conversation.’” The result? “Unlike City College and Long Island University, which never again regained their status as major basketball powers, St. John’s continued to maintain a top-flight basketball program.”

The other hard truth? It’s impossible to control a product when everyone is getting rich but the people doing the work, in this case, the players, which explains the scandals that still plague college sports. Most of the CCNY players apologized, hung their heads, and begged forgiveness.

Some were less remorseful. Shooting guard Herb Cohen probably expressed the sentiments of many amateur athletes when he recalled, “I would look up and the stadium was always full, 18,000. . . . And I would think to myself, ‘Every one of those people paid to get in tonight.’ And where did that money go? Not to me—I was getting maybe five bucks from selling my tickets.”

“I didn’t care,” Cohen said, when asked if he felt bad about shaving points. “I spent the money on clothes. I earned it; I spent it; that’s all. Fuck them.”

Suggested Reading

Judaism’s Feminist Future

For Judith Hauptman, the Conservative push for women’s rights holds the key to its future--and the future of Judaism as a whole.

Jews and the Ukrainian Question

“After the victory,” he wrote to his friend, “we’ll play music—Jewish music, Ukrainian music, and not only.”

Walking the Green Line

New books about the settlers and the settlements and depth and nuance to the discussions about their existence.

Thoroughly Modern Maimonides?: A Rejoinder

To sharpen Stern’s point, we may say that the person who believes God literally gets angry metaphorically angers God.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In