My Scandalous Rejection of Unorthodox

Unorthodox dropped on Netflix on March 26, but the online ex-Orthodox community had already been speculating about it for weeks. It took a day or two for us to binge-watch the four episodes, and then the postmortem began. The series recounts the escape of Esther Shapiro (“Esty,” played by Shira Haas), a 19-year-old newly married woman, from the Hasidic community in Williamsburg to a new secular life in Berlin. Haas, who played Ruchama Weiss on Shtisel, seems to be carving out a niche for herself in ultra-Orthodox roles. In fact, it was a little startling to see her wishing her fans a happy Passover along with others in the cast of Shtisel from her Tel Aviv quarantine, wearing casual clothes instead of an ankle-length skirt.

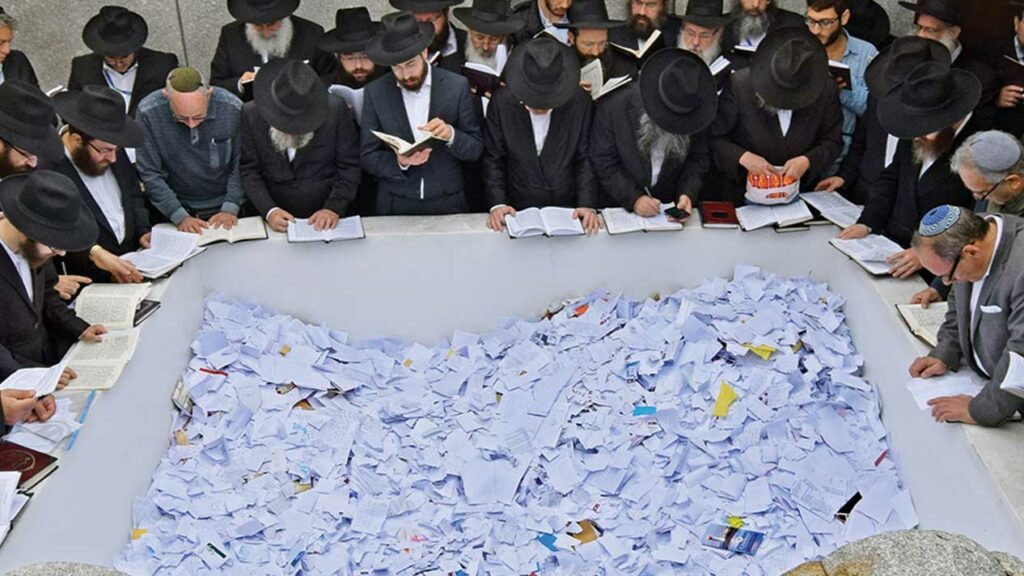

The OTD (off the derekh—that is, no longer on the Orthodox path) social media groups include people from backgrounds as diverse as the Orthodox world itself, and only a few of us have deep and direct knowledge of Satmar, the Hasidic community ostensibly portrayed in the series. (The unnamed Hasidic community of the show more closely resembles smaller, more intimate groups, where a Rebbe might come to a Hasid’s home to discuss a family problem.) But all of us have gone through some version of the transformation Unorthodox dramatizes, and we gobble down and fiercely debate every new OTD memoir that hits the shelves, every documentary and movie that comes out. Our small tribe of defectors is certainly not the intended audience for this growing genre, but we are its collective subject, so we obsess over what they get right (a bit of Yiddish dialect, the right kerchief) and what they get wrong (see below). Call it the problem of OTD translation. We need to explain ourselves: to “outsiders,” where we come from; to old friends and family (to the extent that we can still talk to them), where we’ve gone. As with all acts of translation and leave-taking, something gets lost, someone betrayed.

A small example: In the 2012 memoir from which this show is loosely adapted, Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots, Deborah Feldman calls her grandmother “Bubby,” the pronunciation most common among Ashkenazi American Jews at whom the book is aimed. But Esty, in the series, calls her grandmother “Bobby,” as I called my own. “Accuracy” hardly captures the effect this had on me, the gratitude I felt toward the series (more particularly, to Eli Rosen, its Yiddish translator and cultural consultant) for getting that little thing right. Who knew a vowel could break your heart?

I wasn’t the only one in a state. The days after Unorthodox hit saw a burst of writing on the Facebook groups, particularly by formerly Hasidic women—posts describing what it feels like to shave your head and then to finally and gloriously stop shaving it, kallah classes gone awry, mikvah stories, Hasidic wedding photos, descriptions of awkward first-night sex. There was even a mention or two of vaginismus—Esty’s condition, which makes sex painful for her and complicates the consummation of her marriage. I spend a lot of time in OTD groups, and I’ve never seen such raw writing.

Lots of people with a less personal stake in the subject were also talking about the show’s portrayal of Hasidic Williamsburg. In the Los Angeles Times, Meredith Blake published a piece titled “Netflix’s Unorthodox Went to Remarkable Lengths to Get Hasidic Jewish Customs Right,” praising the writer and director for their commitment to authenticity and describing Eli Rosen’s involvement. (Among other things, he taught Haas how to speak what most people heard as a convincing Satmar Yiddish; Rosen, a regular in the OTD groups, also plays the rabbi.) In a glowing review, New York Times television critic James Poniewozik also weighed in:

There’s an otherworldliness to “Unorthodox,” a credit to how well the director, Maria Schrader (also of the “Deutschland” series), visualizes both Williamsburg and Berlin. The dialogue hopscotches among Yiddish, English, and German; the scenes among the Hasidim are essentially period pieces, meticulously designed and costumed. There’s a sense, which Esty must feel, that the series takes place simultaneously in the past and the future.

After such baselessly confident judgments, it was a relief to hear from Frieda Vizel, who, as someone who left the Satmar community, knows better than Blake or Poniewozik whether Unorthodox did, in fact, “get Hasidic Jewish customs right.” Writing in the Forward, Vizel pointed out that the broken eruv that plays a pivotal role in the first episode, and which is cited by Poniewozik as a symbol for the almost invisible “high walls” that keep Esty in (until they don’t), is an obviously invented plot device. Satmar—along with many other haredi communities—generally doesn’t “hold by” the eruv. But for those viewers with just enough knowledge of Jewish practices to have heard of an eruv, this manufactured plot detail presumably allowed them to imagine themselves in the know.

It’s easy to pass this off as a minor quibble, an inaccuracy easily forgiven for the sake of the larger artistic vision, the symbolism Poniewozik sees in the eruv as the border of the community. But for Vizel, these small inaccuracies are symptoms of a much bigger, if less easily pinpointed, problem. What the show gets wrong, she argues, is basically everything:

I don’t recognize the Unorthodox world where people are cold, humorless, and obsessed with following the rules. Of course, bad people exist in the Hasidic community, and I am critical of many of its practices, but that doesn’t mean everyone goes about muted, serious, drawn, fulfilling the rules and mentioning the Holocaust.

This last part made me laugh. By some kind of cultural contagion, a set of conventions seems to have developed for presenting the Orthodox world onscreen (Shtisel is a notable exception): not only the garb and the song and dance and “sea of black” but also ponderous language, weird utterances, and sepia tones, as if Orthodox Jews lived by candlelight, parsing out stern and sagacious words like rabbinic Yodas or Mr. Spocks. I can attest that the last kitchens in America still lit by fluorescent lights are in Hasidic homes.

It’s just this ponderous quality that Poniewozik was so taken by, the feeling that he was watching a “period piece,” an “otherworldly” combination of past and present that signaled that he was in the presence of “authentic” Hasidism.

While Poniewozik praises director Maria Schrader’s visualization of both Hasidic Williamsburg and contemporary Berlin, the focus on accuracy and authenticity, in his and other reviews, is directed almost entirely at Brooklyn. How did Berlin get off the hook so easily?

Walking in on the scene in which Esty hangs out with a group of music students in the kitchen of their conservatory dorm, my son asked if I was watching reality TV. I could see why; the talented, diverse, outspoken, and sexy young housemates bantering in front of a mural of a tropical beach were as visibly curated, as fabulously and uniformly beautiful and young as the cast of a Coke commercial. He wasn’t the only one who noticed. Along with memories of Hasidic marriages, the OTD groups were full of wry commentary on the ease and speed with which Esty finds her remarkable friends, the young German she gets into bed with, and the teacher and students who help plan her conservatory audition. Was it just me, or was it hard to follow how much time had passed between Esty’s dramatic flight to Berlin and the climactic audition near the end of the fourth episode? A few days? Weeks? Is that really how long it takes to go through the admissions process at a German musical conservatory? And, as someone dryly commented on an OTD Facebook group, “Where were the sexual predators?” She didn’t need to elaborate; we all knew about the dangers of those uncertain first steps “off the derekh.”

I suppose it makes no sense to ask whether the Berlin we see in Unorthodox is “authentic.” The music conservatory that is the story’s major setting is, after all, a complete invention on the part of the writers. In Making Unorthodox, a short documentary appended to the series, the producer, Anna Winger, describes their intention to present an “aspirational” version of Berlin, one very different from the Berlin of Deborah Feldman’s own experience. Feldman moved to Berlin with her young son only years after leaving Williamsburg; Esty makes the great leap in a day. So, that leaves only one context measured for its accuracy by the critics, one scrutinized for its curious customs and strange rituals. What would it mean to investigate and present the sexual habits of that group of people in Berlin, the details of their mating rituals?

This is not to say that we see no sex in Berlin. One scene finds Esty in what looks like the sexiest dance club in Berlin, and the group Esty falls in with includes a gay Nigerian cellist and his blond boyfriend. It isn’t surprising that Esty herself soon gets swept up in a tender (if initially awkward) love scene with the sensitive and hunky Robert in the final scene of episode 3. But the credits roll before we can see how far they get. When episode 4 dawns, they are still in bed, Robert asleep in the morning light. It seems entirely possible that the couple has had sex (though “made love” seems the right euphemism for this gauzy scene). Esty’s vaginismus, perhaps, is cured by Robert’s soft gaze and hard chest, by the ethereal glory of classical music or the pounding techno-rock at the club, or by the same Lake Wannsee current that carried off her wig. Or maybe not. She gets out of bed, wearing a bra and the skirt she was wearing the night before.

There is nothing remarkable about this modestly averted gaze, the cutaway from the tousled bed; we’ve seen those camera angles, heard that music before. In contrast, there is nothing usual, or normal, about all the earlier sex scenes in episode 3, which devote excruciating attention to Esty and Yanky’s year of failed marital sex: Nothing is left to the imagination. A kallah teacher mimes intercourse with her fingers and demonstrates the use of menstrual cloths, we have ample opportunity to witness what Hasidim wear to bed, Esty is handed a tube of lubricant (by her mother-in-law!), and the kallah teacher measures her anxiety with some sort of medical device and hands her a kit of something called “dilators” (look it up, or use your imagination). Esty and Yanky try again and again, and each time is more awful to watch. If these are sex scenes, they are of an entirely different species than the tender Berlin lovemaking. Name another reference to vaginismus in popular culture.

It’s worth pointing out that this shockingly direct depiction of sex—with its odd fusion of the clinical, the ethnographic, and the pornographic—is trained on what surely must be one of the most sexually modest communities in the world. I say “odd” because the prurience of Unorthodox is not Netflix’s familiar pop culture prurience. It’s a pornography not of sex but of sexlessness, of sex denuded of the glamor of what we might as well call Berlin sex, a sex hedged by Jewish law and the imperative to procreate. But this sexless sex is also, apparently, the most exciting sex, because it is so hidden.

Unorthodox’s quasi-ethnographic depiction of what is often described as “an insular community” is also odd, also distorted, insofar as it is driven by sexual curiosity and shaped by the conventions of an escape narrative. Only someone who was on the inside but is now on the outside could ever truly know, and would ever dream of describing, what Feldman’s autobiography and the show attempt to describe. This is an ethnography of horror, which plays and replays the backwardness of its subjects, confirming at the same time the sublimity and joy and freedom and light of modern secular lives, at least as “aspirationally” imagined. It’s a gaze that sees everything except its own hungry eye at the keyhole.

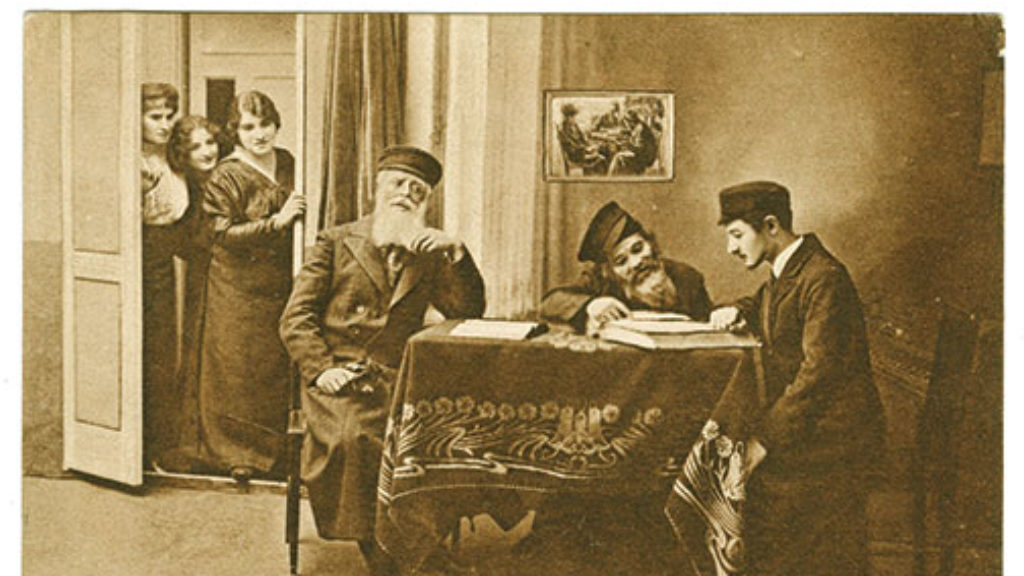

While odd, it’s not entirely unprecedented. Modern Jewish literature began with something like OTD memoirs, which right from the start performed a similar strip show for an enlightened audience. Salomon Maimon’s 1793 Autobiography contains both the earliest literary record of the nascent Hasidic movement and a deep dive into the autobiographer’s years of unconsummated marital sex. (To be fair, he was still a young teenager.) A few decades later, Mordecai Aaron Günzburg’s Aviezer provided even more graphic detail not only about his impotence as a newlywed but also about his mother-in-law’s attempts to “cure” him with near-lethal concoctions. Were the Jewish Enlightenment autobiography not an entirely male phenomenon, we might have seen some vaginismus. In these memoirs, something of Jewish law, its minute attention to the body, was brought to bear on the very different literary genre of the autobiography. These, too, were translations, shaped by the expectations of their readers as much as by their subjects. It’s worth noting that Maimon escaped Poland for the same city Esty chose two and a half centuries later and that he published his autobiography in German, not Hebrew. Even then, exotic Jews were a hot commodity.

There is a passage toward the end of Deborah Feldman’s memoir where she first figures this out. She’s working on an application to an adult education program at Sarah Lawrence as part of a much more gradual defection from the Satmar community than portrayed in the series (but try selling that story to Netflix). “I prepare the essays in advance, handwriting them before typing them up. The first two are autobiographical. I think to myself, This is my shtick. I gotta use whatever I got.” I got into a doctoral program at Berkeley at least partly on the strength of my own OTD story. A lot of us use whatever we got.

In Making Unorthodox, actress Shira Haas grasps for words to describe the power of the story in which she stars, finally settling on the insight, which she delivers with glistening eyes, that it is about “the right to have your own voice.” She was probably thinking of the audition scene: Esty begins by singing a Schubert lied but closes more powerfully by singing a Hasidic wedding song, the very one sung at her wedding, “Mi ban si’ach.” Unorthodox, Haas seems to be saying, is a story of empowerment and individuality, of discovering one’s own voice. Does it matter that this ideal of “finding one’s own voice” has the ring to my ear of the Sarah Lawrence classroom, the Berlin (or Tel Aviv) coffeehouse? It’s in phrases like this one that the OTD story finds an accessible narrative frame that translates (Hasidic) treason into (secular) bravery, (family) abandonment into (individual) empowerment, the mess of human relationships into an epic tale of universal appeal.

And what does Esty sing in this voice that is her own? A Hasidic song from the community left behind. This Hasidic music is also her deepest truth, despite the powerful attraction she thinks she feels to classical music, despite the desperate escape she has made from the community where such songs are sung. Or maybe Esty saw something as clearly as Deborah Feldman did: As a pianist, she didn’t have a chance; even as a singer, the main thing she had going was the story that explained her choice of “An die musik” as her grandmother’s secret favorite. “Why secret?” the judge asks, and her chances for admission skyrocket.

Maybe, just maybe, Esty heard that question and saw her shot. The only way forward was through the one thing she had that everyone wanted, the story of the “insular community” she had left behind. Even the Hasidic song was only what it was because it came with this story of a woman finally allowed to sing, a secret finally “scandalously” shared. Do you believe Esty is too naïve for such calculations? That’s only because she has to be, because only an Esty above calculation lets the secular viewer off the hook. Only an utterly naïve Esty—which is to say a truly authentic Esty—can obscure the nature of the queasy transaction that is the OTD narrative.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?

For the whole history of Jewish society, until less than two hundred years ago, love and attraction played little or no role in the making of marriages, which were arranged and contracted according to the interests—commercial, religious, and social—of the families involved.

Spinoza in Shtreimels: An Underground Seminar

A professor and three Hasidim walk into a bar—to study philosophy. True story.

Nuclear Family

Part of the artistry of Shtisel derives from an almost ritualistic obsession with the details that ultra-Orthodox Jews themselves obsess over.

Ba’al Teshuvah Poetics

Part of being a ba’al teshuvah is the yearning to stop being one—to finally blend with those who never had to return because they never left.

Phil Cohen

By the decision of moving from memoir to fiction, the creators of Unorthodox clearly chose to move away from the contours of the memoir into the world of Netflix art. The show provides, for me at least, precisely what Shira Haas (who, of course, had no role in writing the screenplay) identifies as a moment when a vulnerable young woman comes into her own. The delicious irony of that moment coming through Esty singing a traditional wedding song perhaps connects her back to that world, perhaps in a way similar to that of the generation of Yiddish speaking American comedians who held onto their past even as they moved squarely into America.

As for the harsh characterization of the Satmar community, I've read a couple of OTD types criticizing the extent to which these folks are unfairly portrayed as narrow-minded and humorless. As a total outsider to the Satmar community, I'm willing to give them the benefit of the doubt on that score. But, nevertheless, these are OTD types, having left that world behind for reasons of their own, have their own gripes, else why leave? Perhaps the world awaits the most authentic representation of that world that will elicit the fewest complaints from the OTD types.

Meanwhile, on the other hand, I note that we non-Orthodox types do experience more than a bit of Schadenfruede over our opportunity to watch what we are led to believe are authentic Hasidic tropes unfolding before our eyes, especially joyless sex. This show has been recommended to me so often, that whenever someone even opens their mouth to recommend a Nextflix show, I know the next word will be "Unorthodox," followed by "Shtisl."

Luftmentsch

Far from being "invented out of thin air," wishing mourners a long life is a standard custom in British Jewry. Which, I suppose, shows the tightrope one walks in translating one culture, or sub-culture of a sub-culture, to another.

Diane Gottheil

Thank you for your excellent discussion, both for spelling out what so bothered me about Unorthodox as a theatrical production (perhaps more suited to Lifetime than Netflix) and for describing——based on knowledge that comes from personal experience and scholarship——what they got wrong .

John

You would need a real tin ear for Jewish history to portray Germany as any sort of promised land for any Jew, much less one whose civilization was grotesquely destroyed almost in its entirety by this country. So whether the series gets this or that ritual right should be besides the point.

Mark Roller

Wendell Berry explains his admiration for the Amish by saying that they have rejected the blandishments of Modernity in order to preserve values which they prize as central to a life well-lived. They have, so to speak, chosen to chose what serves their way of life and what doesn't. This in contrast to the majority society in which an ethos of "creative destruction" and constant innovation--in which anything which can be done will be done, if it be at all profitable--relentlessly revolutionizes values, often degrading and eroding them in the process. The Ultra-orthodox have also chosen to chose, although their choices, in respect of details, have been different than the Amish--attitudes towards modern technology, for example. Regardless, these dissenters from modern life deserve our respect. They are traveling a tough road in order to preserve a spiritual vision of life's possibilities that the rest of us have thrown, willy-nilly, to the wind.

In that sense, the Ultra-orthodox help to keep "less observant" and secular Jewry grounded. Although the range of Jewish spirituality is broad, we need somebody to live out the full Judaic religious/cultural synthesis--Judaism as a total way of life. Without that to refer to, so to speak, we risk dissolving in the soup of multi-culti America , our candle lighting, our renewal movements, our Torah study groups just added ingredients spicing things up a little bit. I'm not advocating that we all become Ultra-orthodox. They don't have all the answers. But, we should acknowledge a debt of gratitude to them and the key role they play in the on-goingness of Jewish life in America.

Part of doing that is resisting narratives, even ones generating by other Jews, in which the Ultra-orthodox are seen as only oppressive, enforcing a rigid conformism in which individuals have no voices of their own. We can argue endlessly about how true that is, or is not. The testimony of people within these groups as well as OTDs is vital in this. But let's not forget that in the final analysis, Ultra-orthodox communities were formed originally to pursue transcendental goals. Only their members can tell us if attaining states of transcendence--of spiritual flight--are still a living possibility, or if it has been ossified by Weberian "routinization". It's interesting, in that light, that the truly transcendent moment in Unorthodox is not when Esty finally gets herself free at the end, but when, during her audition, she switches from the classical repertory to a Hasidic song, full of longing and a kind of melancholy joy. Her performance is heart-rending. Might we infer that that song, so expressive of the world she comes from, is her true voice?

Tammy Socher

Ever since Potok's books came out, I have been struck by the lack of depiction of joy and socializing, in popular fiction about the Orthodox world. In "The Chosen," an eligible, employed widower and son are alone, week after week, shabbat after shabbat, looking out the window at the rain, drinking tea. No one invites them, and they have no company. Even in "Shtisel," which is much more realistic, we don't see the constant visiting and bringing people home from shul that are such a part of Orthodox life in all communities. Where are the guests, the people in the community who are always guests (older singles) and passed from house to house, the friends of the children and the friends of friends?

Susanne Klingenstein

Excellent analysis. Brava, Naomi! Hasidism is being trotted out for public display because it's one of the last worlds that is truly closed off. And in the process of being "ethnographically" explored, the series confirms all the stereotypes and dark suspicions the 'enlightened' world already held about the backward Jews and their hellish world. Because that is what sells. The comparison with Salomon Maimon's autobiography is spot on!

yehudah cohn

Luftmentsch beat me to it with the comment above. The wish that a mourner have a long life, so prevalent in Britain, is now often Hebraized as "hayim arukim", although I can remember when it was only said in English. I suspect that the original Hebrew equivalent, from which the expression derived, was the Sephardic blessing "tizkeh leshanim rabot"

Edward Abrahams

There is the added and uncomfortable issue that UNORTHODOX posits that cosmopolitan Berlin represents a viable future for Jews longing to be free, rather than Israel. The German director Maria Schrader indicates that the music conservatory represents her aspirational vision of post-war Germany with people coming together from all over the world to create beautiful music, including a musician of course from Israel, who turns out to lack any social skills as she cuts the heroine Esty to the quick with her cruel critique of her musical talent. I found the implicit anti-Zionist and anti-national bias coming from a German director, no matter how liberal, to be rather rich. The real truth is that without the Israeli actress, Shira Haas, there would have been no UNORTHODOX.

David Henkin

Awesome article. "Name another reference to vaginismus in popular culture." Sex Education, Season 2, Episode 8.

David Lobron

Echoing Edward Abrahams's comment above, I also felt very uncomfortable with the a-historical nature of this series. It has echoes of "White Man's Burden"-style white saviorism. Compare it, for example, to NPR reporter Sarah Vowell in "This American Life" episode, in which she traces her Cherokee ancestors' expulsion from Georgia by Andrew Jackson (https://www.thisamericanlife.org/107/trail-of-tears). The reporter is not shy about criticizing her community's flaws, but she constantly and rightly points out that many of those blemishes were caused or exacerbated by unrelenting persecution. She also tries to show the human dimension of her ancestors, and tell their story in their own terms. Unorthodox does not attempt any of this. The history of why some Hasidics sects mistrust the outside world and modern culture is never explored. The photo above, of Esty standing beatifically in the Wannsee, is particularly ridiculous, considering that it's only feet away from the villa where Hitler and his henchmen planned the Final Solution (the "Wannsee Conference"). It would be like filming Sarah Vowell joyfully casting off tribal regalia, and diving into a swimming pool at the Andrew Jackson Estate.

The praise this series has garnered seems to me a symptom of the fact that oppression of Jews is often invisible to the progressive left. For whatever reason, Jews aren't allowed in the intersectional tent.

Jay D. Homnick

I confess that I stopped reading OTD literature very shortly after I started. The pain was too searing, my powerlessness too abasing. But the threshold each such work must overcome is: why should I believe the community - or the Torah itself - is the problem, rather than your own family or yourself?

Thus the need to establish a narrative of congregational villainy as a backdrop to the courageous escape artist making a run for it "towards the light".

This story comes with an added irony: the early struggles of lovers to overcome technical or psychological barriers to sex can add up to a poignant moment in their journey. I know many couples who believe they bonded more deeply because they lovingly carried each other through the desert, on the way to the Promised Land...

Back in 1980-81, I was paired with a Satmar study partner for several months and I got a sense of how his marriage functioned. There was definitely a charm there, a kind of innocence. I wouldn't romanticize it nor would I demonize it, but it was certainly not oppressive.

Dina Hollander

The whole genre of OTD literature is a real insight, not into the Orthodox community, but to the public desire to see that last isolated stronghold breached. Needless to say, I never recognize the world I live in in these book. We are a community in a world that sorely lacks community (look up loneliness epidemic). We are a community that focuses of family, on relationships, on study, on joy, on collective sorrow and most of all the struggle to make the grind of life meaningful. We are far from perfect (if we were that would by definition be the messianic times) but we are human. We deserve the right to be depicted as deeply human, not as dark fantasies of the secular mind.

OTD people are by deffiniton those who suffered, sometimes from the community writ large but in the vast majority of cases through their own issues or at the hand of loved ones. Instead of treating their writings as facts about the whole community, we need to read them as a highly colored account which seeks to reframe their own struggles as one of overcoming and eventually becoming "free." We all create such narratives of our lives but OTD people unfortunately use the rest of us as their grind stone.

There is also something else that is unspoken when OTD people try to explain their journey--temptation. By temptation I mean simple human temptation in all its many forms. It's like the classic story with the Orthodox kid who went to college and met a beautiful non-Jewish girl. All of the sudden he finds himself filled with doubts about his lifestyle, filled with sorry memories of his "repressed" youth. What comes first in many cases--the doubts or the girl? Why must we believe all these accounts of "personal liberation" when they could simply be a complete surrender to what they want?

Likewise the OTD genre is by definition very self selecting. It usually shows the ones that made it far enough to write a book. It doesn't show the many that go OTD but find their way back or those who simply self destruct. I only know a handful of OTD people--yet ALL of them hit rock bottom, suffered severe substance abuse, some tempted suicide (one succeeded) and had terrible relationships. I remember hearing my father often lament that in the past kids went OTD for the GREAT idea--be it Zionism, revolutionary communism or be a great artist or even to make LOTS of money. But today, he would say, they go OTD beast of "whatever", to do drugs or the like. Where are the philosophers like Miamon or the poets like Bialik to name two famous OTDs. It sometimes looks like the last successful generation of OTD kids was in the 1970s. Even the few examples of relative success seem like bundles of emotional mess when interviewed.

To say that all to often OTDs complete breakdown is is because of lack of training in the Orthodox community about drugs and the like is silly. We are trained day and night that we cannot eat this or that, cannot do this or that. We have build masses of muscle memory and true grit regarding refraining from this or that. All that should carry over but it doesn't. To say it was because the community at large rejected them, that parents threw them from home is nonsense. OTD kids in 2020 get super sensitive treatment. The OTD kids I knew were living at home, their parents lovingly making space for a kid that break every rule and broke their hearts in the process. As I only knew a few cases, these are not exactly a fair projection about all cases but in these cases it was simply because too often the OTD path is one of going after the unallowable and then just wallowing in it. The greatest joy to a parent of an OTD kid is simply to see that child successful because all too often they see them simply self destructing.