The First Maggid—How Memory Made the Jews

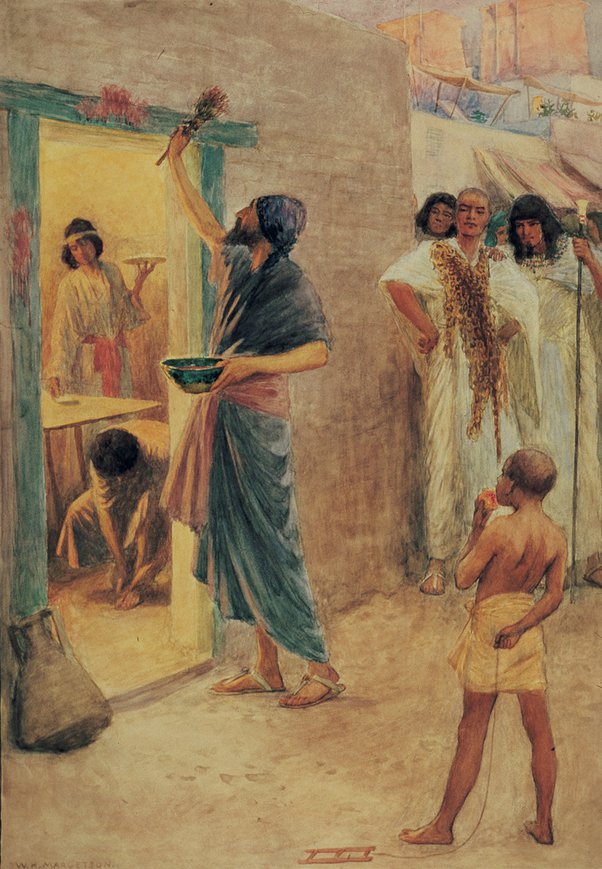

Imagine you’re an Israelite adult 3,500 years ago. The kingdom that has enslaved you, your parents, and your parents’ parents has been ravaged by plagues. You’ve watched (and been spared) the carnage, but now, you’re told, you need to do more than look on. Your family will publicly pledge allegiance to the deity supposedly responsible for the plagues or the tenth one will afflict you together with your oppressors. You kill a lamb and paint your doorpost with its blood to signal that your firstborn has faithful parents. Your children see these things and they ask. . . well, they ask why tonight is different from all other nights.

You don’t tell the children they were once slaves in Egypt, because that’s all they know. But it wasn’t always so, you tell them––long ago, their ancestors enjoyed over a century of freedom under God. God chose to raise the patriarchs up from the idolatry of their native culture and to give them a covenantal life. A famine some generations later compelled the chosen family to live in Egypt, first as guests and then––until now––as slaves. Tonight, God will keep his promise to the patriarchs and restore the Israelites to his service.

What the parents of the Exodus told their children was the very first maggid––the first telling of Passover night. But the story as originally told didn’t commemorate the founding of the Jewish nation. Telling the story founded the Jewish nation.

Until the Exodus, the before-time of the patriarchs was a rumor whispered by strangers subjugated in a strange land. On the Exodus night, teaching the children about God’s choice of Abraham converted his descendants into his self-conscious heirs. A free nation was created by restoring a memory of itself. The pageantry of the Seder is often and correctly said to recreate the Exodus night in order to tell a story. The reverse is also true. Jews recreate the Exodus night in part by telling a story that the Exodus parents must have told their own children 3,500 years ago, and with the same function––initiating youngsters into the chosen people of God.

If the Haggadah’s discussion of Abraham’s idolatrous origins is meant to recreate the original maggid on the eve of the Exodus, it helps explain its otherwise puzzling location in the text of our Haggadah. Abraham’s origins appear, not at the beginning of maggid where they chronologically belong, but towards the middle. That placement is a compromise between two talmudic interpretations of the mishnaic ruling that we must begin maggid by mentioning the Israelites’ ignominy (genut) and end with their honor (shevach). One school said the initial low point was Abraham’s pagan lineage; the other school said it was our enslavement to Pharoah in Egypt. The final text of maggid includes both ideas––albeit with our slavery (Avadim Hayinu) mentioned before our patriarchal origins. This means that the official proceedings of the Seder night unfold out of chronological order. The four questions are asked, then answered with Avadim Hayinu. Next come the nocturnal rabbis in Bnei Brak and the four sons and other vignettes. Only after all that do we go back to Abraham.

Why not just answer the four questions with the idolatry of the patriarchs’ native land and tell the story straight through, from covenant to slavery to redemption, noting in passing the talmudic dispute about where maggid ought to start?

Avadim Hayinu, the famous response to the four questions, doesn’t really tell a story. Rather it tells about telling a story:

We were slaves to Pharoah in Egypt, and the Lord our God brought us out with a strong hand and an outstretched arm. If the Holy One had not brought our ancestors out of Egypt, then we and our children and our children’s children would still be enslaved to Pharoah in Egypt. And even though we are all wise, and understanding, and old, and learned in Torah, we are obligated to tell the story of the Exodus from Egypt.

Nothing like this could have been uttered by the first generation that left Egypt. Avadim Hayinu is the justification expressed by a people living long after slavery for revisiting a sorrowful period of national history. We’re collectively remembering why we’re collectively remembering.

Avadim Hayinu summarizes a story about God’s gift of freedom. That gift is sustained precisely by the act of its beneficiaries recognizing it as a gift. The adults at the Seder know the story of freedom. But just as this night’s adults had to succeed their parents, they’ll need successors of their own. The Seder’s purpose is for adults to help those listening to the story to learn how to tell it themselves. With the four questions, the children at the Sedertable have asked why tonight is different. They are ready to be students. The parents reply that to be a student is not enough! The students of freedom should listen with an eye to becoming teachers of freedom––old and wise and learned in Torah.

After summarizing the story and the purpose of the night, parents invite their children to think about different aspects of our duty to remember the Exodus. The tale of the rabbis in Bnei Brak is about the fervor with which the story should be told. And about the limits of that fervor––a captivating Seder doesn’t get you out of morning prayers. Next vignette: Rav Elazar ben Azarya, as wise as a man of seventy, credits his colleague ben Zoma for explaining the obligation to remember the Exodus all the nights as well as all the days of one’s life. And though it’s often an occasion for silliness, the story of the four sons is the most serious of all. Passover is the one night of the year parents must include their children in deliberations about how to parent, which of course compels children to think about how they themselves might parent someday.

The paragraphs immediately following Avadim Hayinu don’t recall the Exodus, they recall the act of recollection. They aren’t maggid, they’re meta-maggid. This self-referential aspect of the whole evening strikes some people as bizarre. But the Haggadah is paying the children a serious compliment. The vignettes and the rules introducing the story of the night raise the children who ask the four questions to the self-consciousness of Jewish adulthood. It is an honor, though it is also highly necessary. By contrast, the children who asked their parents about the lamb’s blood on their doorposts 3,500 years ago did not need to be told why they should ask for answers. The wonders around those children simply demanded an explanation. They asked for one and the answer made them young members of the nation. But in the absence of those miraculous initial conditions, children not only have to ask, they have to be taught why they have to ask.

Once the act of telling the story is interpreted and the children know what listening properly involves, the story itself can begin much as it would have begun 3,500 years ago––“our ancestors began as idolators, and now the Lord has taken us into His service.” Abraham was the son of Terach, who served other gods. God took Abraham from beyond the river to a new land and a new way of life. Abraham sired Isaac, who sired Jacob, who went with his sons in Egypt, and whose descendants were enslaved but are now to be freed.

The Exodus parents would have ended their maggid with the events their children lived through. But the story at our Seder tables continues through the parting of the Red Sea, the destruction of Pharoah’s army, receiving the Torah, the forty years in the desert, the conquest of the land of Israel. . . the whole roll call of miracles listed in every child’s favorite song of the night––Dayenu. Telling the story of the patriarchs recreates the very first Seder night, and recalling the events that followed the Exodus recreates successive Seder nights. Each of those nights extends the first Passover night’s purpose, to make a nation remember itself into existence.

Suggested Reading

I, Terrorist

Whither the great anti-American novel?

History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

On-screen, Mel Brooks was hysterically funny. Off-screen, he could quickly shift to morose or mean.

Ordinary Memory

“I wanted to write an integrated history,” Saul Friedländer told a magazine in 2007, in an interview marking the long-awaited concluding installment of his Holocaust study Nazi Germany and the Jews. By “integrated history,” Friedländer meant one in which the designs of genocidal perpetrators were fused with the personal testimony of the victims. “Business-as-usual history flattens the interpretation of mass…

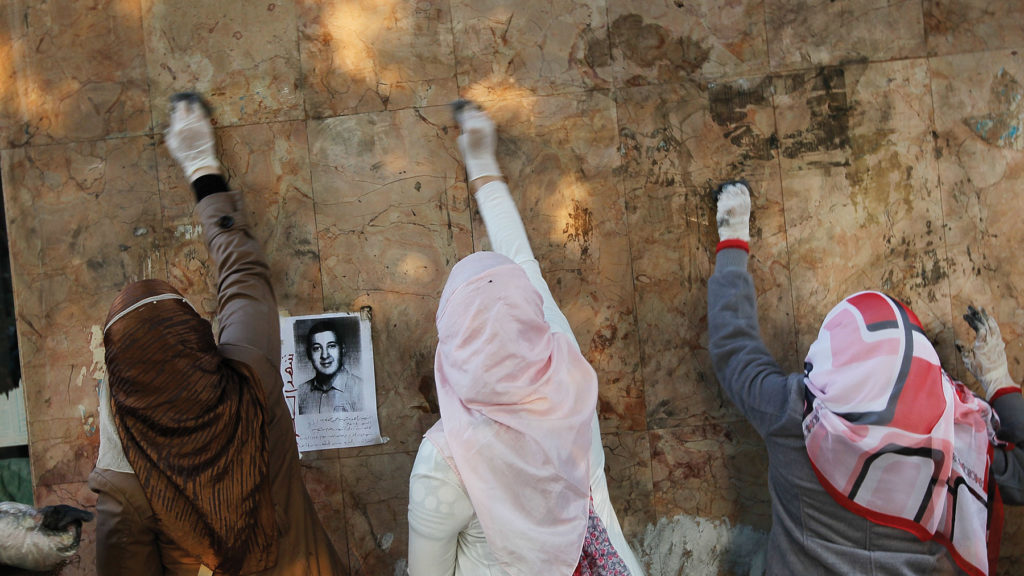

Trashing Dictatorship in Cairo

Tahrir Square isn't the only thing Egypt's democrats need to clean up before democracy takes hold in their country.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In