Trashing Dictatorship in Cairo

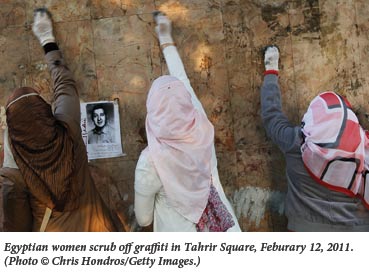

Hussein Ibish of the American Task Force on Palestine and Daniel Pipes of the Middle East Forum—two observers each inhabiting distant points on the political spectrum—reported being struck by the same item that hit me from the uprising in Egypt. Following the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak and the subsequent decision of the protest movement to vacate Tahrir Square, leaders called on participants to return the next day to clean up after themselves. And they did.

I’ve visited Egypt a handful of times and was surprised to discover how much I liked it, above all for the unparalleled warmth of the people. But one thing that has shocked me is the seemingly universal disdain for public places.

On a train from Alexandria to Cairo, I watched a large man, clothed in a threadbare dishdasha and sandals, consume a bag of sunflower seeds. As he chewed the seeds, he tossed the husks on the floor, creating a mound in the aisle. I’ve seen comparable behavior among the well-off. In 2005, I interviewed reform-minded presidential candidate Ayman Nour at his home, a large luxurious flat, filled with high-end technology and elegant Egyptian antiques. A broad, landscaped patio led to a swimming pool. But to get to his apartment, I had to make my way through unlighted corridors and an elevator that reeked of neglect. Puzzled, I was told that Egyptians lavish care only on their private spaces.

On a train from Alexandria to Cairo, I watched a large man, clothed in a threadbare dishdasha and sandals, consume a bag of sunflower seeds. As he chewed the seeds, he tossed the husks on the floor, creating a mound in the aisle. I’ve seen comparable behavior among the well-off. In 2005, I interviewed reform-minded presidential candidate Ayman Nour at his home, a large luxurious flat, filled with high-end technology and elegant Egyptian antiques. A broad, landscaped patio led to a swimming pool. But to get to his apartment, I had to make my way through unlighted corridors and an elevator that reeked of neglect. Puzzled, I was told that Egyptians lavish care only on their private spaces.

What the Tahrir cleanup signified to me was that the protesters want to open a new chapter in their history. The larger evidence of this was, of course, the general peacefulness of the protests.

When I blogged about the burning of the National Democratic Party headquarters as an exception to the non-violence, a young Egyptian activist I know wrote me plaintively that he and his colleagues believed that government agents had done this as a provocation. I’m not so sure, but I noted how pained he was by the allegation, which he took as a stain on the honor of his movement.

Although Egypt was in the forefront in this respect, the idea of non-violence was evident elsewhere in the region. The New York Times reported from Oman that “Protestors at [a] vigil in Sohar . . . said they regretted the burning of a supermarket . . . and other acts of violence, which they said were carried out by a small band of excited young people.” No doubt, non-violence wherever possible has been a wise tactic, but perhaps this choice and the Tahrir cleanup also signal the birth of a new sense of civic honor in the region.

One source of this change might be that Arabs remember being burned by revolution before. Starting with Egypt in 1952, revolutions swept across the Arab world. The outcomes could scarcely have been worse: Each of the new Arab “republics” proved more tyrannical than the regime it supplanted. In fact, in recent times the most liberal of the Arab states—Morocco, Kuwait, Jordan—have been the surviving monarchies. To add insult to injury, every one of the revolutionary rulers tried to engineer a dynastic succession, although only Hafez al-Assad succeeded. Indeed, Mubarak’s wish to pass the presidency to his widely reviled son, Gamal, may have been the straw that broke the back of public acquiescence in Egypt.

A Syrian activist tells me that the conspicuous absence of revolutionary leaders is no accident, but “reflect[s] an innate suspicion . . . born out of our past experiences where our revolutionary leaders turned into corrupt and corrupting dictators. I think adopting the right revolutionary means will pave the way [to] the right revolutionary results.”

To say that these are all encouraging signs is not to say that all signs are encouraging. One cannot praise the revolt without recalling the vicious assault on CBS reporter Lara Logan by an estimated 200 men who beat and molested her while screaming, “Jew! Jew!” Apart from the raw ugliness of this crime, it points to issues that stand between Egypt and democracy, or at least liberal democracy.

The virulent anti-Semitism is well known. Less so is the pathology of relations between the sexes in the Arab world. An Egyptian feminist group recently issued statistics saying that 83 percent of Egyptian women and 98 percent of female visitors to the country had experienced some kind of molestation. The survey was not rigorous, but whatever the true numbers, the practice is shockingly common. In Najib Mahfuz’s great novel Palace Walk, the protagonist, Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad, spends every evening carousing while his wife waits for his late-night return so that she may bathe his feet. Listening to his (sanitized) accounts of his day’s activities is the high point of her day. Mahfuz’s novel was set in the 1920s, but the intervening century has brought little progress. In her 1992 novel, the celebrated Egyptian novelist, Ahdaf Soueif, portrays a young woman who defies her parents to marry the love of her life. He whisks her off to London, installs her in a fine apartment, and, after she behaves shyly on their first night together, never pays attention to her again. A leading Egyptian female blogger and activist told me that she did not know of a single Egyptian man who was faithful to his wife. And a male of the same generation told me he knew of only one happy marriage.

Does this have anything to do with democracy? After all, democracy began in the West when women had few rights. True enough, but there were traditions of courtliness missing in the Arab world where, rather than “ladies first,” women have been expected to walk behind their men to display subordination. Democracy presupposes a recognition of our common humanity. A failure to see this in Jews might not be fatal—if there are no Jews around. But failure to see it in women is incompatible with the virtues on which democracy depends.

A more immediate worry is the Muslim Brotherhood. A week after the conclusion of the Cairo protests, the spiritual leader of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, returned to Cairo and held forth at a Friday celebration in Tahrir Square. Despite efforts of various apologists to whitewash him, Qaradawi is a bloodthirsty racist who has urged the killing of Americans in Iraq and Jews everywhere. He writes that a climactic battle “between . . . all Muslims and all Jews” is a “precondition [to] the day of judgment.” On this particular Friday, in response to Qaradawi’s sermon, listeners chanted: “to Jerusalem we go; martyrs in the millions” and “Today Egypt; tomorrow Palestine.” When Wael Ghonim, the Egyptian Google chief who was the hero of the revolution, sought to address the crowd, Qaradawi’s entourage blocked him from the podium.

If there is scant reason for equanimity about how the Brotherhood would behave if it gained control of Egypt, there is however considerable hope that this will not happen. As has already been widely noted, one of the most remarkable things about the upheavals in Egypt and elsewhere has been how marginal the Islamists have been. Opportunistic politicians like Mohammed ElBaradei or Ayman Nour may pander to the Brotherhood, but the secular youth in the forefront of the protest movement dislike and fear it as much as we do.

Will democracy issue from the current miraculous moment? In many of these lands the odds are steeply against it. But in Egypt it might take hold, and that would be momentous. Egypt has been the political, cultural, and intellectual heart of the Arab world, though its influence has waned in these decades of stagnation. An Egypt with a lively democratic process and a free press would quickly regain that preeminence and serve as a model others would likely follow sooner or later.

Suggested Reading

Write a Modern Letter, Live a Modern Life

Imagine that you’re a woman living in a shtetl in 1900: what do you say in a letter to your husband in America if you think he’s cheating on you?

Unfinished Rock

Why is the last stanza of Ma'oz Tzur unlike all other stanzas?

From Venice to Harlem

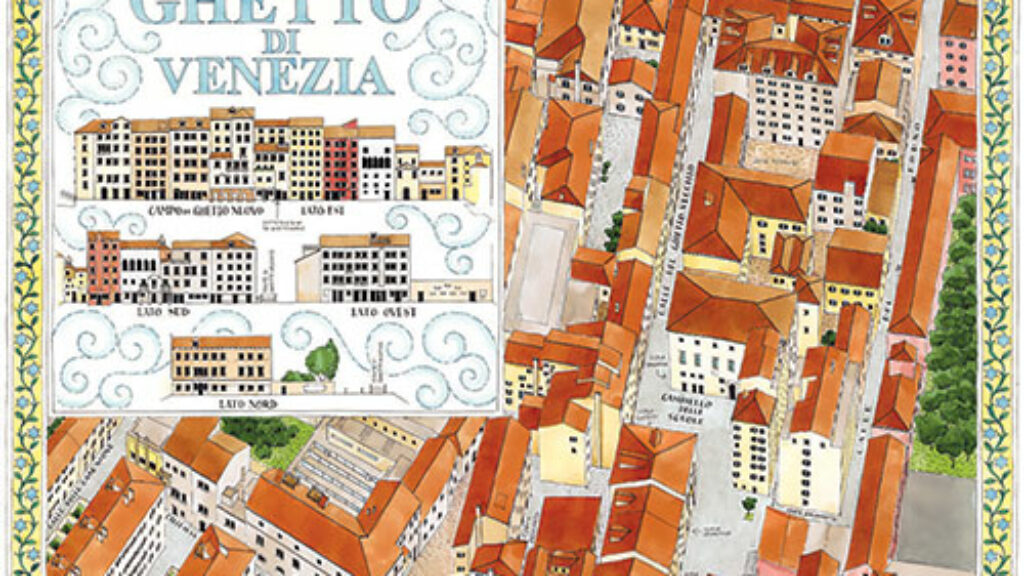

Faced with a bewildering variety of uses for the word “ghetto,” Daniel B. Schwartz performs marvels of clarification in steering the reader through the labyrinthian twists, turns, and hidden alleyways that mark this terminological odyssey.

Kidnapped!

When Ruth Blau met with Khomeini to secure the safety of Iranian Jews, it was only the latest extraordinary meeting for the fifty-seven year old Resistance spy turned convert turned kidnapper turned anti-Zionist turned Israeli agent.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In