The Wry Comedy of A. B. Yehoshua

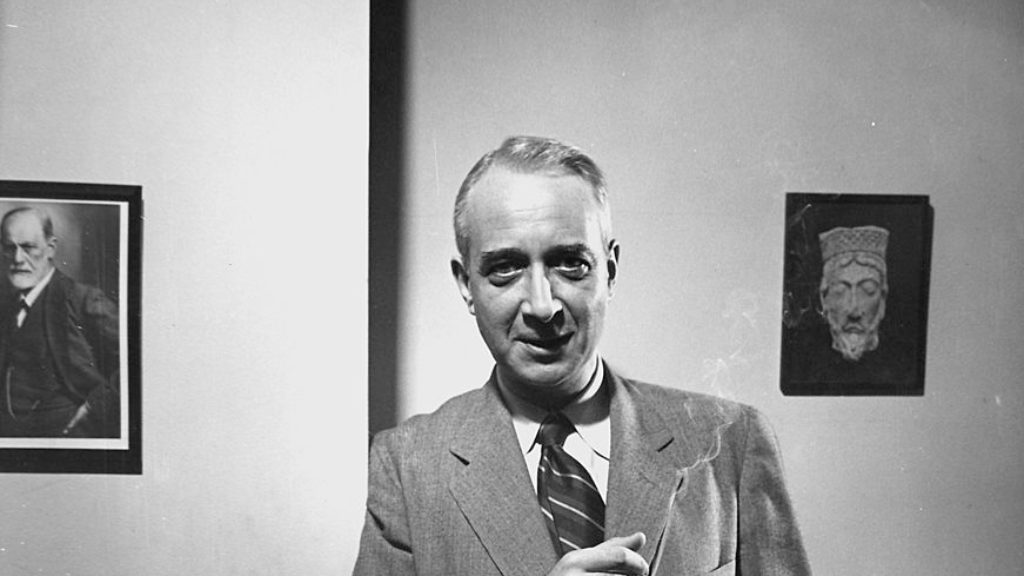

A. B. Yehoshua, who died June 14, 2022, at age eighty-five, was one of the most fascinating writers of the past several decades. To those of us who were his friends, he was an endearing man, always spontaneous, an eminent figure who never preened and never cultivated a public persona, passionate about the things that were important to him—sometimes exasperating but still endearing in his passions. My own friendship with Yehoshua began in 1969 after I had written an article in Commentary in which I celebrated him and Amos Oz as the two most promising talents in Hebrew fiction.

Buli, as all of us who were close to him invariably called him, was an unswerving advocate of the classic Zionist view called shelilat ha-golah, the categorical rejection of Jewish life in the diaspora. It was especially in this regard that he could be exasperating. Though he was a warm and generous person, he insulted American Jews for living in the wrong place and thus faking their Jewishness at more than one public forum. Some twenty years ago, for instance, I contrived to bring him to Berkeley as a Regents Lecturer. This lectureship is designed for writers and artists who are not conventional academics. The Regents Lecturer visits classes, meets with students, and delivers one public lecture. For the lecture, I tried to persuade Buli to speak on a literary topic, perhaps on writing historical novels or the stylistic challenges of writing fiction in Hebrew. However, he was adamant; he had a new theory of antisemitism that he wanted to present to the Berkeley audience. Predictably, few of those present bought the theory, and when a young woman, who happened to be my doctoral student, posed a question he didn’t like, he responded with a vehement ad feminam attack: I am ten times more of an authentic Jew than an American Jew like you, he told her. He could not have known that she was a fluent speaker of Hebrew, had dual American and Israeli citizenship, and had gone back to Israel to do her requisite two years of army service.

He could be just as truculent in private. In 1982, during a year’s stay in Israel, my wife, the translator Carol Cosman, and I had gone to Haifa to give talks at the university, she in French and I in Hebrew. Buli and his wife, Ika, together with Hillel Halkin and his wife, Marcia, had taken us out to dinner at a Chinese restaurant. During the course of a friendly conversation, Buli proclaimed that for an opinion setter in the American Jewish community to encourage followers to remain there was like a family living on a busy street that still allows their children to play outside after one of them has been hit by a car. My wife, never intimidated by eminence, was indignant and told him that this was a preposterous analogy. Buli, who was not someone inclined to yield to objection, insisted on the aptness of his comparison.

It seems to me that there was a fundamental discrepancy between the positions Buli embraced on historical and political matters and his literary practice as a novelist. In his fiction, he was alive to ambiguity, ambivalence, contradiction. In his thinking about history and national conflict, he aspired to the role of heavy-duty intellectual and drew pictures in black and white. In this regard, he was quite different from David Grossman (another of his close friends), who, when he writes about Palestinians and Israelis, thinks—usually to great advantage—like a novelist. In Buli’s last few years, for example, having despaired of the feasibility of a two-state solution, he espoused the notion of a single state in which Israelis and Palestinians would learn to live together in amity. His friend Amos Oz, much more of a political realist, argued till his final days that this was impossible, given demography, ideology, and a hundred years of mutual bloodshed and hatred. A single state would inevitably become a Palestinian state from the Jordan to the Mediterranean, with the Jewish minority either persecuted or driven to flee. For Oz, the option of two states, however unlikely at the present moment, had to be clung to because the alternative was too dire. Yehoshua, it seems to me, did not look very hard at the likely consequences of his position.

Let me hasten to add that as a person Buli was a much more affectionate, engaging, loyal friend, and a man with a good-humored sense of self-irony. The last time I saw him, not long before the pandemic curtailed international travel, I was in Jerusalem with my youngest son. Buli asked him what he did for a living, and my son explained that he designed men’s clothing. Buli’s quick response was: “Maybe you can design something to hide my stomach!”

There is a prevailing notion in the Hebrew criticism of Yehoshua’s novels that they are all about Jewish history, Zionism, and the future of the nation. To this end, critics have dutifully unearthed national and historical motifs, freighted allusions to the Bible, and interrogations of the Zionist project. Some Hebrew critics have come close to turning his stories and novels into national allegories. None of this is altogether off the mark. What such readings miss, however, is the charm of his novels. They also forgo any explanation of how his work has kindled enthusiasm among Americans, Europeans, and others who could scarcely be expected to be much interested in Zionism, the Jewish people, and Jewish history. It’s worth remembering that Buli was also a comic novelist. Granted, the comedy of his fiction is offbeat, deadpan, and often concerned with the grimmest realities of life, from obsession to dementia. Still, reading Buli’s wry descriptions and bizarre scenarios, one often cannot help but smile.

The template for this weird strain of comedy was set in his second book of fiction, Facing the Forests, a volume of four novellas. What these novellas share are protagonists who are drawn to the brink of destruction. The protagonist of the title story, who has been assigned to be the watchman of an Israeli forest, actually goes beyond the brink by becoming the passive accomplice of a maimed, mute Arab who sets fire to the forest. There is nothing funny about this story, which seemed to express a kind of suicidal impulse in the Israeli psyche, but the other stories consistently find the humor in dark subjects.

The most striking example among these stories is the novella “A Long Hot Day, His Despair, His Wife and His Daughter.” The protagonist, an Israeli engineer, has been stationed for an extended period in Africa to oversee the building of a dam. While there, he is invited to witness a tribal ritual that involves feverish dancing. An African teenage girl, naked from the waist up, emerges from the dance and abruptly sits down in the engineer’s lap. In the moment, he freezes. Afterward, he finds himself emotionally paralyzed. When he returns to his home in Israel, he cannot work and hangs around the house, dazed, in his pajamas. He becomes obsessed with his teenage daughter and her emergent sexuality, which he finds he cannot comfortably accept.

Early in the story, the daughter’s boyfriend goes off to perform his military service, and he writes her a series of love letters from his army base. The father intercepts the letters at the mailbox and reads them without giving them to his daughter. Later, when the boyfriend shows up for a visit, he and the engineer have a strained conversation, the odd tenor of which puzzles the young man. At the end of the story, the father tries to jump-start his recalcitrant car by rolling it downhill and inadvertently bumps into the boyfriend, breaking his glasses without seriously hurting him. Feeling a wave of guilt, he kneels by the car and awaits his wife, thinking, “This time she will really run him over.”

All this, of course, is crazy. The spectacle of the engineer’s obsessive behavior, puttering around the house barefoot, even lying down in his daughter’s bed when she is out of the house, makes him a bizarre figure of fun. Characteristic of the way the protagonist’s obsessions in these stories play out in the plots, the protagonist’s direst impulses are never realized: nothing untoward happens between the engineer and his daughter; he does not actually run over the boyfriend; his wife will not fulfill his self-punishing fantasy. It was part of Buli’s bleakly comic genius to find the humor in such situations.

Since Buli had a lifelong involvement in psychoanalytic thought, surely in part influenced by his wife, who was an analyst, critics have been quick to identify the odd behavior of his protagonists as an eruption of the unconscious, dark urgings of the suppressed pushing toward the surface. It is quite likely that Buli often had such a Freudian dynamic explicitly in mind. But the psychoanalytic model, which scarcely allows for comedy, in part misrepresents what goes on in his fiction. The subject that powerfully engages Yehoshua as a writer is how a perfectly ordinary person can find himself edging by degrees into behaviors that are altogether unreasonable, on occasion grotesque, and, often, bizarrely comic.

I should add that not all of Buli’s comic touches were connected with dark obsessions. My favorite such moment is in The Lover, when an Arab teenage boy is invited by his Jewish boss to Friday night dinner. The appetizer is, of course, gefilte fish. The boy takes a first mouthful of the unfamiliar dish and his palate is outraged by the unwelcome sweetness, a physical experience of his finding himself in cultural terra incognita: what do these weird Jews eat?

Elsewhere, the comedy is in Yehoshua’s droll descriptions. His last novel, The Tunnel, vividly illustrates this. Though about the decline into senility of a character named Zvi Luria (yet another engineer), written when Buli himself was aging, it abounds in amusing formulations. Thus, Herod is referred to as “the admirable King Herod, who ruled our nation for almost forty years, and was like the Office for Public Works and Israeli Roads rolled into one.” The young civil engineer with whom the failing Luria comes to work as a senior consultant is described as the man “to whom Dina [Luria’s solicitous wife] ingeniously appended her husband as an unpaid assistant, so that he could, on the advice of the neurologist, fight better, with the help of roads, interchanges, and tunnels, against the atrophy gnawing away at his brain.” The beguiling touches here are in the use of the verb “appended” and in the literalization of the neurologist’s counsel. At the beginning of the book, when Luria starts his Japanese car, “he thought he heard . . . a brief soft murmur amid the gargle of gears and pistons, the voice of a Japanese or Korean girl, possibly planted in the electrical system to wish the discriminating driver a safe trip in his new car.” Elsewhere, she is referred to as “the whispering geisha.” Everywhere, drollness abounds.

Buli did not always admit to the fancifulness in his fiction. After reading A Journey to the End of the Millennium when it came out in Hebrew in 1997, I called and tried to tell him what a delightful fantasy it was. He immediately objected: the book was historically authentic, as he had been assured by medieval historians he knew.

Let me sketch the outlines of the plot, which should show the degree to which it is obviously a playful fantasy. It is the end of the tenth Christian century, shortly after Rabbeinu Gershom had banned polygamy among what we would now call Ashkenazi Jews, at least in part in response to the fact that they lived among Christians, for whom polygamy was anathema. (Yehoshua antedated the prohibition a little for narrative convenience.) Rabbeinu Gershom’s ban did not apply to Sephardi Jews, many of whom continued to have multiple wives. The novel’s main character, Ben Attar, a resident of Tangier, has a prosperous business exporting North African goods to his widowed nephew, who is living in France, and the two meet annually in Spain to divide the profits.

The marital fly in this mercantile ointment is that the nephew has recently married an extremely pious Ashkenazi woman, a blonde and blue-eyed Jew from the Rhineland, who regards with horror the fact that Ben Attar has two wives. Despite the success of the family business, she wants her husband to break off all relations with his polygamous uncle. The uncle’s solution to this problem is to pack up both wives, one older and the other young, hire an Arab sea captain, and sail up along the Atlantic coast, into the English Channel, and then up the River Seine, to the then-provincial village of Paris to demonstrate to his nephew’s new wife how well polygamy actually works.

This whole idea is surely an entertaining fantasy, as is the middle-aged Ben Attar’s sprinting from one end of the ship to the other en route to provide conjugal gratification, first to one wife and then to the other. Once the Sephardi entourage has arrived in France, Ben Attar convenes a rabbinical court to adjudicate this dispute with a set of jurors composed of women. It’s a delightful conceit in a genuinely funny novel, but its anchorage in history is, let’s say, tenuous.

Buli was constantly trying out new modes of fiction, and his playfulness was on display in a different way in his 2013 novel, The Retrospective. The Hebrew title, Hesed Sefaradi, means Spanish, or Sephardi, charity. The title alludes to a painting by the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Matthias Meyvogel, Caritas Romana, which depicts an odd Roman tale about an aged father who is imprisoned by the state and deprived of all food so that he will die by starvation. His daughter, having recently given birth, visits him daily and, in the privacy of his cell, sustains him by breastfeeding him. When the authorities discover what she has been doing, they are so moved by her devotion to her father that they release him.

The protagonist of the novel, Yair Moses, is a prominent Israeli filmmaker now in his seventies. He has come to Spain to attend a celebratory retrospective of his early films. Teasing the Hebrew reader, Buli offers plot summaries of these films, which turn out to be the plots of stories from his Kafkaesque first book, The Death of the Old Man. The scriptwriter with whom Moses worked early in his career, a certain Toledano (a Sephardi name), has for many years been bitterly estranged from him because the director suppressed a scene he wrote that, unbeknowest to him, reinvented the story of “Caritas Romana.” When Moses returns to Israel after the retrospective, the director and the screenwriter have a tense meeting in which Toledano tells Moses that he will only agree to a reconciliation if Moses returns to Spain and actually reenacts the tale of the old man and the nursing daughter.

In Spain a strong young peasant woman is hired to take part in this act. As she exposes her ample breasts, Moses oddly imagines her as Don Quixote’s beloved Dulcinea. The novel ends with the act consummated, the reconciliation between the one-time collaborators effected. All this, of course, is very peculiar and, by the standards of realism, scarcely credible, but transposing the Roman story and the Dutch painting into novelistic space is a quintessential expression of Buli’s propensity to place his protagonists in situations that lay bare the potential for grotesque comedy of the human condition. We are not exactly expected to laugh, but there is nevertheless something quite laughable about Moses becoming the old man at his daughter’s breast of the Roman story and at the same time Don Quixote. Like A Journey to the End of the Millennium, this is a book that pushes against the envelope of novelistic realism.

The Tunnel’s protagonist, Zvi Luria, is suffering from progressive dementia, hardly a laughing matter. In the opening scene, at a visit to his neurologist, he is informed that a recent brain scan shows a dark spot that will inevitably grow. Luria, a retired road engineer, is understandably terrified by the prospect of his inevitable decline. All that the neurologist can suggest is that he keep active and perhaps try to do some work. His memory loss accelerates as the novel develops, and Luria’s anxiety about it is scarcely allayed by his wife’s sympathetic devotion. Yet there are comic aspects to his plight. He has the code he needs for starting his car tattooed on his arm, but what will he do if he has to replace the car or for some reason has to use a new code? At another point, on a work trip, he loses his cell phone, and to play it safe, he replaces it with two phones. How he will remember two different numbers remains to be seen. Perhaps another tattoo?

Though already in retirement, Luria has been enlisted as a consultant to plan a road in the Negev desert, probably for military use. The new road will require the demolition of a hilltop where a Palestinian family, a schoolteacher, his son, and his beautiful daughter, have taken shelter after having illegally entered Israel from the West Bank. These Palestinians speak fluent Hebrew, the son and the daughter almost without an Arab accent. When Luria asks about their origins, they refuse to identify themselves ethnically. On top of that, the hill turns out to be the site of an ancient Nabataean settlement, a people who were neither Arab nor Jewish. Perhaps, one of the squatters suggests, they are actually Nabateans—and Buli’s characteristic fancifulness seeps into the dialogue. So, of course, does the idea of an ambiguous or fluid identity in Israel-Palestine with which Buli had repeatedly toyed over the years.

The configuration of an older man drawn to a young woman or girl that we have observed elsewhere recurs here as well. Luria is attracted to the beautiful young illegal immigrant, but he is a loyal husband and resists any impulse to act on the attraction. In another book, Return from India, Buli reverses this pattern, having a young physician become smitten with his boss’s wife, who is old enough to be his mother. All these instances lead one to suspect that Buli’s fiction is less a map of the Jewish condition, as some of his critics have contended, than a map of his own psyche. I don’t mean to say that all these instances are either programmatic or inadvertent representations of a Freudian Electra complex. Rather, Buli was fascinated by the comic, wandering ways of sexual desire.

The Tunnel concludes on a note of somewhat ominous hilarity. Luria’s dementia has progressed to the point where he has forgotten his own name. Returning to the hilltop alone, he meets the Palestinian schoolteacher, who addresses him, saying, “Zvi, Zvi, aren’t you Zvi? So here’s another zvi,” as he points to a deer (in Hebrew, zvi) that has appeared nearby. Luria “accepts the return of his name with excitement and gratitude,” as though his lost name were a set of keys or an identity card that has been misplaced. The Palestinian then lifts the rifle he has been carrying and shoots the deer. Is this some kind of sacrificial substitute for Zvi Luria? Yehoshua’s last novel is amusing, even beguiling, but also dead serious.

To cite what is perhaps a more typical proportion between the beguiling and the serious, let me turn, finally, to the conclusion of Mr. Mani. That book, as some readers will recall, begins in 1982 and moves backward in time from chapter to chapter, ending in 1848, and it is made up of dialogues in which the words of only one of the two interlocutors are given. (This second technique was employed by the Argentine writer Manuel Puig and only a few other writers; there may be no precedent in literary history for the first technique.) The last of the Mr. Manis, then, in the order of presentation is the earliest one in historical time.

This last Mr. Mani, like so many Yehoshua protagonists, is in the grip of an obsession—that the Arab inhabitants of Palestine are actually Jews whose ancestors converted to Islam in the wake of the Arab conquest more than a thousand years earlier, an idea that was entertained by a few figures in early Zionist circles. As we have seen, the notion of a fluid national identity had considerable appeal for Buli, whose own ancestry can be traced back to “Arab” Jews. This earliest Mr. Mani decides to act on the idea, and so he goes roaming through the narrow streets of the Old City trying to persuade its inhabitants that they are really Jews and must return to their original Jewish identity. This is, of course, crazy. The absurdity of Yosef Mani’s quest is funny, but he ends up getting killed by Arabs, which is no joke.

In its closing pages, this novel effects a last turn of the screw of absurdity. Yosef Mani has left behind a childless young widow, Doña Flora. His aged father proceeds to enter her bed and beget a son with her, thus becoming the father of his own grandchild. This perplexing act is probably intended by the novelist as a variation of the biblical obligation of yibbum, levirate marriage. In the classical case of yibbum, the brother-in-law of a childless widow must take her in marriage with the responsibility of fathering a male descendant who will count as the offspring of his deceased brother. In this case, as with the biblical story of Judah and Tamar, it is the father-in-law rather than the brother-in-law who takes the deceased’s place.

All these quirky conjunctions and couplings, or at least intimations of potential couplings, are the strongest evidence that A. B. Yehoshua was not an altogether realistic writer. On the contrary, his fiction often proves to be a vehicle for the play of fantasy. In this, I would suggest, lies the secret of his appeal for readers across the globe.

At the very end of his life, Buli wrote a brief novella in the form of a play titled “The Third Temple.” It centers on a woman who has come to an influential rabbi in Tel Aviv to request that he denounce a Parisian rabbi who, enamored of her, contrived a legal device years earlier that made it impossible for her to marry the love of her life. At the end of her presentation to the rabbi, she tells him of her passionate belief in the importance of rebuilding the temple. It proves, however, to be a whimsically utopian fantasy of a Third Temple. She wants it put up as a modest structure in a neighborhood of west Jerusalem well outside the Temple Mount, so as not to impinge on the sacred spaces of Islam and Christianity. Also, there are to be no animal sacrifices, only celebratory song. Yehoshua’s final text is not comic, but it is a comedy in the sense that it has a happy ending in the woman’s fantastic vision of a rebuilt temple that will avoid conflict and bloodshed.

Buli, needless to say, was urgently concerned with sounding the depths of his people’s bewildering and often murky history and trying to make out how Zionism might provide a viable response to the challenging ambiguities of the Jewish condition. This urgency led him, as I observed at the outset, to propose “solutions” for the persistence of antisemitism, the quandaries of diaspora existence, and the dilemmas of living in a land ardently claimed by two conflicting peoples, which were implausible or unworkable. As a novelist, however, he often used the vehicle of fiction to indulge playfully in whimsical ideas and situations rather than polemics. His work reminds us that fiction can be entertaining, and perhaps should be, even when it is serious.

Delight is by no means the whole of Buli’s legacy as a writer, but it is one of his work’s prominent features. Now that he is, alas, gone, it is something for which we as readers should continue to be grateful.

Suggested Reading

Man of Letters

Adam Kirsch’s judicious selection of Lionel Trilling’s letters throws instructive light on both Trilling’s life and American intellectual culture from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Spanish Charity

The sight of a secular Israeli artist in a cathedral confessional in Spain is one of the more interesting moments in recent Israeli fiction. A new novel by A.B. Yehoshua.

Judaism’s Feminist Future

For Judith Hauptman, the Conservative push for women’s rights holds the key to its future--and the future of Judaism as a whole.

Coming with a Lampoon

Jacobson is a world master of the art of disturbing comedy and each new work of his advances the genre—his latest one by a giant step.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In