Spanish Charity

In Israel A. B. Yehoshua is considered a national asset, and each new novel provokes the kind of intense public debate that is usually reserved for issues of national security. When The Retrospective first appeared in Hebrew in the winter of 2011, the veteran critic Avraham Balaban gave it a stinging review in Ha’aretz. In characterizing the novel as wooden, over-intellectualized, and self-indulgent, Balaban made it sound as if Yehoshua had let down the nation. By spring of that same year, the eminent literary scholar Dan Miron had already written and published a book in defense of the novel. Comparing it to Federico Fellini’s film 8 1/2, Miron argued that it represented a magisterial summing up of Yehoshua’s literary achievements.

The recent appearance of the novel in Stuart Schoffman’s fluid English translation provides a chance to consider it not only after the heat of the initial debate has cooled, but also within a different critical climate. Despite Yehoshua’s best efforts to provoke American Jews with dismissive remarks about the diaspora, his fiction is esteemed in the United States. Precisely because the reception of Yehoshua’s novels is not so fraught outside of Israel, there is a chance for more perspective.

The new novel completes what might be called Yehoshua’s Sephardic trilogy, which began with Mr. Mani and continued with A Journey to the End of the Millennium, each of which addresses the idea that the experience of Jews from Mediterranean lands whose ancestors were exiled from Spain provides a unique cultural contribution to Israeli society. The centrality of the Sephardic theme is made explicit in the original Hebrew title of the new novel: Chesed sefaradi, Spanish or Sephardic charity. (Chesed as a concept is itself not easy to translate.) Mr. Mani is, by all accounts, one of the great achievements of Israeli literature, but so subtle and reversible are its cultural dialects that you can read it over and over again without truly knowing what Yehoshua means by Sephardic identity or culture. Less ambitious and more narrowly focused, The Retrospective provides Yehoshua with a setting for a more coherent working out of his ideas on this subject, ideas which, after all, may have shifted since the appearance of his chef-d’oeuvre more than twenty years ago.

To approach the question of Sephardism from a new angle, in The Retrospective Yehoshua exploits a key difference between writing novels and making movies: The authorship of a novel is vested in one person, whereas a movie is made not only by the screenwriter, but by the director, the cinematographer, and even the actors. In this unapologetically autobiographical novel, Yehoshua casts himself as the director. The character, Yair Moses, hails from the elite Ashkenazi neighborhood of Rehavia, but the other members of his creative team are North African Jews who came to Israel as children and grew up in southern development towns. The “retrospective” of the novel’s English title is a screening, at a Spanish film festival, of a half-dozen films they made together in the 1960s before a disagreement between Moses and his screenwriter broke up the team. This is the stroke of genius: Yehoshua takes the cultural antinomies of his own soul and externalizes them as separate characters in the novel, the better to scrutinize them individually and understand their interdependence.

At the heart of these films is Moses’s partnership with his screenwriter, Shaul Trigano. As a boy, Trigano received a scholarship that allowed him to escape his backward desert town and enroll in the elite Ashkenazi high school in Jerusalem where Moses teaches. Trigano becomes smitten with the power of the cinematic image while working as an usher to make ends meet in Jerusalem. The student succeeds in inspiring his teacher with his artistic enthusiasm, so much so that when Trigano finishes his army service and puts together a small film crew from his hometown, Moses lets himself be talked into becoming the director. Thus Moses is rescued by his student from following a conventional career as a professor and is given the chance to find his calling as an artist. They go on to make six films together before a bitter separation. Although unpolished and made on a shoestring, those films possessed the severe beauty of artistic and existential extremity. Moses goes on to become a successful mainstream director, while Trigano leaves movie making for teaching.

Moses, the Ashkenazi, represents rationalism, education, the weight of the European cultural tradition, secularism, discipline, professional achievement, and the aspiration toward harmony and articulation. Trigano, the Sephardi, is identified with the raw pain of deprivation and abasement. At the same time, there is a greater openness to mystery and the kind of religiosity that comes from the soul in extremis; the power of the primitive enables an understanding of the human condition that penetrates social constructions. Trigano’s two friends from childhood add more traits to the Sephardi side of the ledger. The cinematographer Toledano brings a mystical strangeness to their shoots, and the beautiful actress Ruth brings a resourceful expressiveness that can be molded into many shapes by the writer and director. Admittedly, these are clichés from the culture wars that are wide open to the charge of essentialism. But Yehoshua has always been unapologetic about trafficking in big ideas, and he stakes his claim as a novelist on his ability to press ideas into the service of fiction.

The conceit of The Retrospective is that these artists, with their distinct cultural formations, are joined in a genuine creative process for the durations of the six films that they make together. The rupture between Moses and Trigano comes when, in the final symbolic scene of their last project together, the script calls for Ruth (who is Trigano’s lover) to offer her bare breast to a beggar to nurse. When she refuses and Moses comes to her defense to protect her from this grotesque abasement, Trigano is outraged that his creative vision has been betrayed and cuts off all ties with both Moses and Ruth.

It is not until decades later, during the present time of the novel, that Moses finally owns up to the fact that it was in fact he who provoked the break-up to free himself from Trigano’s allegorical obsessions and make movies that represent everyday life and the material world. He went on to make mainstream but critically well-received films and didn’t look back until forced to do so by the Spanish retrospective.

When Moses arrives in the cathedral town of Santiago de Compostela to receive his prize and serve as the guest of honor at the film festival, he is surprised to discover that it is only his early surreal films, made with Trigano, that are scheduled to be screened; the rest of his career has been ignored. How is it, after all, that a film school in a remote pilgrimage city in Spain should single out the obscure early works of an Israeli filmmaker? Toward the end of the three-day festival Moses discovers Trigano’s fingerprints behind the scenes. The sponsoring institution is not only a film school but a film archive, and, in order to make sure there is a permanent record of his achievement, Trigano had deposited the films there and come to Santiago to oversee their dubbing into Spanish.

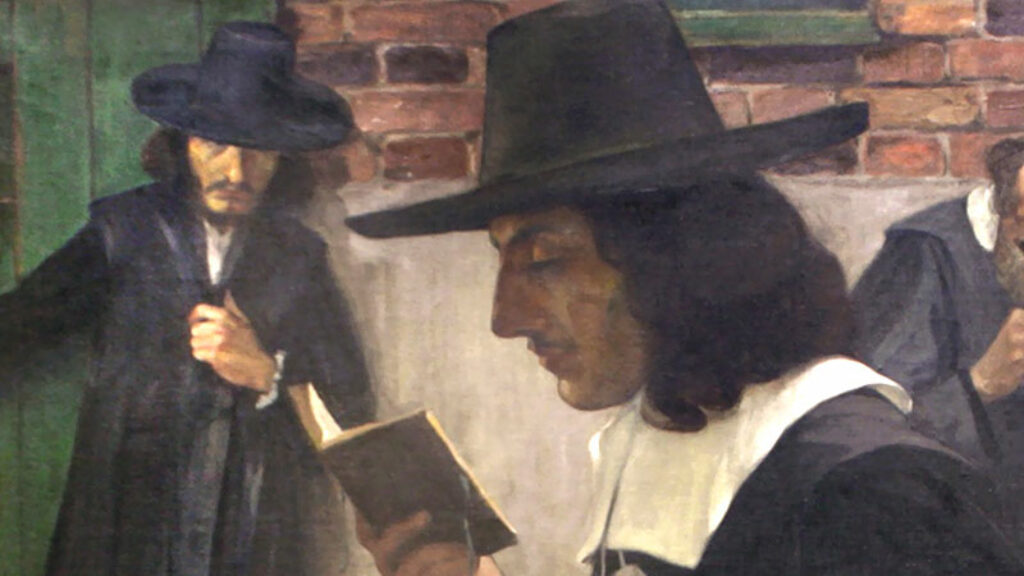

While in Santiago, Trigano came across a 17th-century painting that depicts a woman offering her breast to an older man. The scene, it turns out, is based on a famous story recounted by the Roman historian Valerius Maximus about a man named Cimon who is condemned to death by starvation and his daughter Pero, who, having recently given birth, relieves his suffering by offering him milk from her breast. The title of the painting—and the name of the motif, which was depicted by dozens of European artists—is Caritas Romana (Roman Charity), which Yehoshua adapted for the Hebrew title of the novel: Chesed sefaradi.

Moses has brought Ruth to the festival as his companion, and Trigano sees to it that a copy of the painting is hung above their bed. During the three days of the festival, the film director and his leading actress are obliged to systematically re-experience the period of their tense but creative partnership with the alienated cinematographer. The exposure to the painting works its own magic; Moses comes to acknowledge that the scene that broke up their collaboration, the one in which Ruth was called upon to offer her breast to a beggar, could well have expressed empathy rather than abasement. Moses’ complacency is breached, and he comes to terms with the fact that he is stuck in an artistic impasse from which he can emerge only if he can reconnect with the wild imagination of his former collaborator. In the second half of the novel, which begins when Moses returns to Israel from Spain, the director continues his spiritual retrospective by revisiting the sites where the early films were shot and by seeking out Trigano, who loathes him but also reluctantly realizes that his own fate as an artist has gravely suffered because of the severed relationship.

The first half of the novel takes place entirely in Spain, and the choice proves fascinating on several counts. Spain is not only the land of the Inquisition, which remained virtually judenrein for six centuries, but also the land of the Judeo-Arabic Golden Age and the ur-Sepharad—the Hebrew name for Spain—that gave birth to the original mystique of Sephardism. Santiago de Compostela, moreover, bears an uncanny resemblance to Jerusalem, the city of Moses’s birth. Both cities are vaunted destinations for pilgrims; the parador in which Moses and Ruth stay is a former hospital for pilgrims. Both are modern cities that contain within them old cities swarming with tourists who wander between stalls of trinkets and majestic houses of worship. Moses experiences in Santiago precisely what he as a liberal, secular Israeli cannot allow himself to experience in his own land: the pull and the poetry of religion. Moses is struck not only by the throngs of the simple faithful but also by the way in which religion and modern art are wrapped around one another. The head of the film school happens to be a priest whose mother is a famous actress. He has a warm affinity with Moses and Trigano’s early films because their symbolic and surreal style, after the manner of Buñuel, touches on the mysteries of existence.

At the climax of the Spanish half of the novel, Moses enters a confession booth in the Santiago cathedral and confesses his artistic sins. He has prevailed upon the brother of the film school head, who is a Franciscan brother and also a cinephile, to hear his confession, although he insists that he does not want absolution. On one level, this is all jokey and provocative play-acting. Moses claims he has always been curious about the mysteries of the confessional but had never entered one in Israel because all the priests are Arabs with mixed motives. But on another level, he genuinely seeks the chance to articulate and take responsibility for his part in breaking with Trigano, driving him away and thereby losing a piece of the integrity of his own artistic conscience.

The sight of a secular Israeli artist in a cathedral confessional in Spain is one of the more interesting moments in recent Israeli fiction. An American Jewish reader with a modicum of Jewish knowledge might well be forgiven for looking up from the text and wondering aloud, “This is curious. Don’t we have our own mechanism for confessing and remitting sin?” The answer is yes, of course, and it’s called teshuvah. The process of teshuvah, which was given its classic formulation by the greatest Sephardi of all times, Moses Maimonides, lays out a series of steps that move from regret to acknowledgement of sin to confession (directly to God, unmediated by a priest) and to changed behavior. Indeed, this is precisely the script Moses’ follows when he returns to Israel from Spain and conducts a “retrospective” of his life. He seeks out Trigano, tries to make things right, and even accepts the perverse penance demanded of him, which requires him to return to Spain to reenact the scene of Caritas Romana with he himself playing the role of the bound, nursing father.

As a secular Ashkenazi, Moses is constitutionally incapable of understanding his experience in terms of any Jewish spiritual concept because the fruits of religious culture have been thoroughly poisoned by a century of Zionist ideology and the moral dissipation of ultra-Orthodox. A confession booth in Catholic Spain turns out to be the only way Moses is capable of having a religious experience of contrition. The recognition of this sad state of affairs, one would like to be able to report, is one of the achievements of this novel. But it is not the case, alas, and if the reader comes to this awareness, it is without Yehoshua’s help. The inability to appreciate the resources of his own religious tradition has been an issue for Yehoshua throughout his career.

Still, Yehoshua is too astute a novelist to disregard the religious dimension of human experience even if he is allergic to the traditions of his own culture. What Trigano had brought to their partnership was not religion in the formal sense but a kind of penetrating longing for meaning that transcended the here and now and verged on mania. It was Moses’ role to keep it in check, or as Ruth describes it to him:

[Y]our creative partnership with him was thanks to your normalcy, your sense of proportion, on the assumption that you, as director, would impose credibility and restraint on his wild imagination, that you would calm the disquiet ranging inside him, clarify the symbols that raced around in his soul.

Now, normalcy is a freighted term in the world of Yehoshua’s discourse. As a Zionist thinker and critic of the diaspora, he has often spoken out “in praise of normalcy,” a condition that he argues diaspora Jews are incapable of achieving. Moses in fact sounds very much like Yehoshua the thinker-critic once he no longer has to restrain Trigano’s wildness and is free to express his “normalcy” in films that are this-worldly and realistic and take delight in the material world. The problem is that these films are also tinged with artistic mediocrity. Whereas the novel presents detailed description of each of the early movies, we are told nothing about his later endeavors, except, that is, for the title of one commercial success tellingly titled Potatoes.

The self-knowing strength of The Retrospective is that Moses is brought to the humbling recognition that the way of normalcy is insufficient. Moses may resemble Yehoshua the essayist, but Yehoshua the novelist is closer to the difficult but essential matrix of Moses plus Trigano, Ashkenazi and Sephardi, normalcy and religious feeling. Longtime readers of Yehoshua will surely recognize in this dialectic the shape of the master’s career, which began with severe allegorical tales and moved toward the finely observed psychological realism of A Late Divorce and The Liberated Bride. Yet despite this move away from allegory, what strengthens the claim for A.B. Yehoshua’s being the greatest Hebrew novelist is the rustle of higher meanings that attends his every incarnation.

Suggested Reading

State, Power, Religious Control: How COVID-19 Raises New Political Questions: An Exchange

Between rabbinic rulings and public policy: a response from Daniel Goldman and Yossi Shain and a rejoinder from Yehoshua Pfeffer.

Strategic Imperatives

In his new book, Charles Freilich examines the question of how future governments ought to cope with Israel's fundamental defense predicaments.

Exit, Loyalty … Crowdsource?

It is a bit of a surprise to open a big-think policy book on the fate of the Jewish people and read a Jason Bourne scene with a prep-school payoff, but Tal Keinan is entitled to it.

Radically Enlightened Jews

Jonathan Israel is a minyan of modern revolutionaries.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In