When Canines Were in the Land

“If a Jew has a dog, either the dog is no dog or the Jew is no Jew.” With the possible exception of ultra-Orthodox Jews, this old proverb no longer holds, but it’s worth remembering that the reconciliation between Jews and dogs is relatively recent. There is a story to be told here, and Rudolphina Menzel, who was a great “canine pioneer,” both as a scientist and as a Zionist, is a large part of it.

That a female scion of Vienna’s wealthy bourgeoisie would become either of these things in the years before World War I was not likely. It was only by accident, when she came across a discarded copy of Herzl’s newspaper Die Welt, that Rudolphina found her way, already in her childhood, to Zionism. Her unusual receptivity to the Zionist message may have had more to do with her sufferings as a stepdaughter than with the Jewish problem, but once she was in the movement, she never left it.

Menzel seems to have made a habit of reading whatever she could get her hands on. She once picked a brochure off her father’s desk about a new school established by Socialist reformers and persuaded her father to send her there. At the Freie Schule, Menzel became very close to her home economics teacher, Leopoldine Glockel, who was also, along with her husband, one of the leaders of the Austrian Social Democratic Party. The Glockels turned her into a socialist, but—hard as they tried—they could not uproot her Zionism.

Later, as a student at the University of Vienna, she overcame resistance to the participation of a woman “in the serious and exclusive Theodor Herzl Zionist College Students Club,” turning one of the members who opposed her, in fairly short order, into her husband. Rudolph Menzel became a physician; Rudolphina, for her part, earned a PhD with a dissertation on the sugar compounds in urine.

No direct path led Menzel from excretions to cynology (the scientific study of dogs). She and her husband were living in Linz after World War I when she first became a dog owner. This was not unusual for someone whose family was as far from the ghetto as hers was, but it was only the beginning. Soon she was entering her boxer named Mowgli in competitions. In 1921, Mowgli won sixth place in the Munich Dog Show, impressing the judges with his quick responses to commands in what was to them a strange language (Hebrew, in which he was exclusively trained). But Menzel, explains Susan Martha Kahn, the editor and main author of this consistently eye-opening volume, was not content with owning and showing dogs; “she wanted to . . . systematically breed and study them.” In May 1922 she and her husband moved into a house outside of Linz, surrounded by doghouses, where she started to do just that.

Menzel soon “collected an extraordinarily large amount of data that enabled her to make a series of bold conjectures about the differences between inherited and acquired individual traits.” And in later years, she deepened and broadened her research into canine heredity and behavior. But Menzel didn’t just study dogs; she bred and trained them to contribute actively to modern society. “Her ‘Linzer Boxers’ soon became known as an outstanding line of obedient, strong and courageous dogs with excellent aptitudes for tracking work, making them much sought after by Austrian, Swiss and German police and military units.” In short order, she became a cult figure in the German-speaking world of police-dog training.

Menzel received a royal welcome when she visited police and military headquarters as a consultant, and she presided, at home, over an unusual salon that was a magnet for dog enthusiasts from all over the world, who discussed “the ancient origins of dogs, the sociology of wolf packs . . . and the evolutionary processes of canine domestication . . . long into the night.” Needless to say, there weren’t many Jews among the Menzels’ guests, but the couple never hid their Jewishness or even tried to downplay it. For one thing, Rudolphina continued to train all her dogs to respond only to commands in Hebrew.

Although they were steadfast Zionists, the Menzels don’t seem to have contemplated aliyah until, with the Anschluss of Austria, it became necessary. Before that, however, they had done much to bridge the gap between dogs and Jews in the Land of Israel. In 1927, after years of cajoling, Rudolphina convinced the Jewish Agency to send two kibbutzniks to her to learn how to train guard dogs. They returned to Palestine with two of her boxers. Eventually, after other groups of incoming pioneers had done the same, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, one of the leaders of the Yishuv, invited her to Palestine to teach the Haganah to train and use dogs.

After arriving in Palestine in October 1934, her first stop was on Mount Scopus, where she met with Naphtali Herz Tur-Sinai, a Bible scholar and linguist from Germany who had recently joined the Hebrew University faculty. She needed his help to produce the first dog training manual in Hebrew, which necessitated the coinage of some new terms. The picture Kahn paints of two fastidiously dressed yekkes sitting in a rudimentary new building on a “hot rocky hilltop . . . on the edge of the Judean desert translating a German dog-training manual into Hebrew” is a good reminder of how down-to-earth even some of the most erudite Zionists had to be.

But Menzel didn’t stay in the less than half-built ivory tower for long. She didn’t need the new manual to begin training Haganah members to use dogs to identify, frighten, and pursue intruders and spent some time doing so at various kibbutzim. She also met with high-ranking Jewish Agency leaders, including Ben-Zvi and Moshe Shertok (later Sharett), lectured to general audiences about service dogs, performed dog tricks for children, and evaluated the Palestinian dog population, which Kahn calls a “sickly hodgepodge,” for breeding purposes. Proud of the small cadre of dog trainers that she had left behind to continue her work, she returned to Europe, deeply impressed by what she had seen in Palestine. “I found a free people,” she wrote, “free despite limits on immigration and the like. . . . I had regained my faith in humanity.”

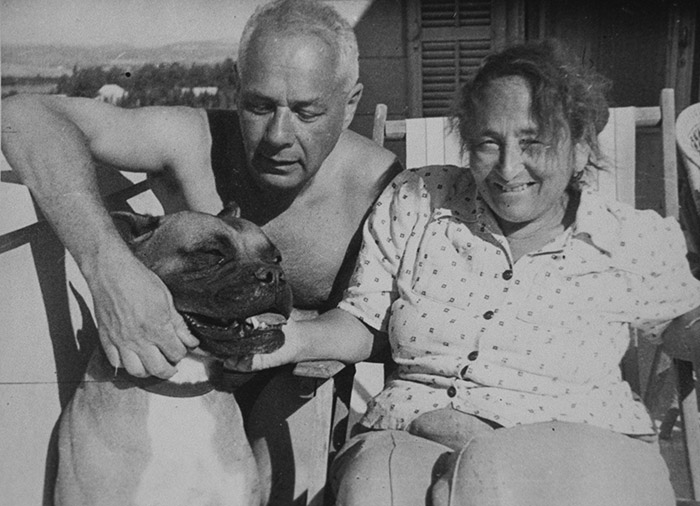

What she witnessed back in Europe in the mid-1930s couldn’t leave that faith intact. But even though Nazism was making inroads everywhere, the Austrian Cynology Association insisted, as late as 1935, that she and her husband represent Austria at a big international cynological congress in Germany. Even more surprisingly, Der Hund, the official German publication for dog sports, published a picture of the Menzels bearing the caption “The German researcher couple from Austria” next to a picture of Hitler and Göring.

The Menzels visited Palestine again in 1937, this time for two months. When they returned home they quickly felt a distinct worsening of the atmosphere. Nevertheless, Rudolphina remained “on very good terms with the local Boxer club, which in January 1938 presented her with a polished crystal trophy bearing an inscription in her honor written by one of Linz’s most well-known Nazis.” Nothing like that would happen again after Germany annexed Austria in March. “On May 25, 1938, the provincial government ordered the cessation of dog keeping on the Menzels’ property and the ‘immediate removal of the Jewish kennel.’” By the fall, Rudolph and Rudolphina were in Palestine for good.

The Menzels weren’t the only Zionists from their part of the world to escape just in the nick of time. Among the other refugees who came to Palestine the very same year was Martin Buber, who had been Rudolphina’s Zionist mentor, as Kahn observes—though not quite in the way she suggests. While Menzel imbibed the heady nationalism Buber propounded before World War I, there is no reason to think that she also adopted his later utopian vision of—as Kahn puts it—“a multicultural Jewish homeland in which Jews lived in harmony with Muslims and Christians in Palestine.” After settling in the Middle East, she worked with the militants, not Buberian binationalists. As Kahn herself tells us, “Like most Zionists of her day, she did not give much thought to the consequences of Zionist settlement for the native Arab populations.”

The Menzels quickly established the Palestine Research Institute for Canine Psychology and Training at their home in Kiryat Motzkin, near Haifa. Among other things, Rudolphina devoted a lot of time to capturing and training feral dogs to compensate for the shortage of trainable dogs in Palestine. She also helped make ends meet by composing a memoir for a Harvard University essay contest on “My Life in Germany Before and After January 30, 1933.” Kahn notes that the “$125 second place prize she received in February 1941 must have been very welcome ($125 is the equivalent of about $2500 today).”

Menzel did everything she could to teach the skeptical and wary Jews throughout Palestine to enjoy dogs and to appreciate their usefulness, even “inviting curious neighborhood children to hold and play with her assorted litters of puppies in Kiryat Motzkin.” By 1944, she was publishing her own typewritten, mimeographed newspaper, called Hakalban (The Dog Handler). She did a lot to dispel both “the traditional Jewish ambivalence towards dogs as well as the Zionist resistance to them as bourgeois affectations.”

In 1942, when the Germans were still threatening Palestine, Menzel wrote to the British authorities proposing “a mobilization of the dog-material, similar to that which is being arranged in England now.” The British took her up on this offer, and she soon supplied them with hundreds of mine-sniffing dogs, which were put to good use in defending Egypt, and thus the Yishuv, from the Nazis. But she did this only conditionally: The British had to agree never to use these animals against the Jews in Palestine. They agreed—and kept their word. After 1945, when British forces were tracking down Haganah and Irgun arms caches, they used only dogs trained in Europe and South Africa. And, when the time came, Menzel helped the members of the underground to thwart these foreign dogs.

On occasion, she used her professional knowledge of the dogs’ capacities to assist in some highly dubious operations. In 1945, some Haganah members took revenge on a Jordan Valley Arab who had sexually molested a number of Jewish women. Dismayed by what they perceived to be the British failure to bring him to justice in a timely fashion, they decided to kidnap and castrate him. Menzel didn’t participate in this grisly operation, but she did advise the team how to evade the British police dogs that would inevitably be sent to track them down.

When Moshe Dayan urged her to focus on “utilizing dogs as weapons of war,” she trained dogs to carry messages and ammunition, to sniff out mines, and to perform “kamikaze missions to destroy enemy tanks using a tactic she borrowed from the Russians.” In the final months of 1947, when full-scale war was on the horizon, Menzel was driven around Palestine to find pets and stray dogs that could be usefully pressed into service. Naturally, she expected to be placed in charge of the IDF’s canine unit when it was established in 1948, but to her great dismay, the position was assigned to one of her earliest protégés. “Now that they were at war,” Kahn speculates, “the young Jewish soldiers weren’t going to take military orders from an eccentric, fifty-seven-year-old woman with a heavy German accent, no matter how much of an expert she was.”

While the magnitude of the role played by the hundreds of “four-legged soldiers” serving in the IDF in the War of Independence has never been properly assessed, there was at the time “widespread understanding that dogs had contributed to the Jewish victory.” The Arabs, hampered by traditional Muslim beliefs about the uncleanliness of dogs and lacking a Rudolphina Menzel of their own, had no dogs of their own in the fight.

The army absorbed the Menzels’ research institute, but at fifty-seven, Rudolphina wasn’t ready to retire, so she founded the Israel Institute for Orientation and Mobility of the Blind. The institute concentrated on training guide dogs for the many people—both Arabs and Jews—who needed them but were deeply wary of them. She also resumed her purely scientific work and, among many other things, developed Israel’s national breed, the Canaan dog. At age seventy-one, Menzel was appointed associate professor of animal psychology and director of the Institute for Ethology at Tel Aviv University in 1962. She remained active until her death eleven years later.

The final essay in this volume, by Tammy Bar-Joseph, addresses the question that many people who know a lot about the Yishuv and Israel will ask themselves long before they reach it: Why have I never heard of this amazing person before? If you haven’t (and nobody I know has), Bar-Joseph suggests that it has less to do with what she was—a woman, a scientist, and a yekke—than with what she was not: “She was not a mother, she was not a farmer, she was not a politician, she was not a soldier, and she was not a war hero.” She just didn’t fit into any of the most familiar boxes of collective memory. In the history of cynology, her pioneering work has also failed to receive the recognition it deserves—in part, Kahn suspects, because it wasn’t translated into English and in part because other researchers have somewhat discreditably obscured their indebtedness to it. I don’t know how much even an outstanding academic book like Canine Pioneer can do to alter this state of affairs—but if its contributors could find the right Israeli TV producer, Rudolphina Menzel’s story could be the basis for a series that would make her a household name around the world.

Suggested Reading

Radical Kindness and Heroic Dogs: A New Anthology of Yiddish Children’s Literature

Honey on the Page, like the best anthologies, is an eye-opening work of literary history, gleefully introducing a sea of lightly known authors through both their work and through meticulously crafted biographical sketches.

How Jews Were Modern

What’s a nice Jewish boy doing making bronze statues of tsars? And does it count as Jewish culture? Ahad Ha’am wanted to know and the Posen Foundation’s ambitious new survey raises the question afresh.

An Al Schwimmer Production

When the ancient Spartans sought to aid a friendly state in distress, they did not send troops or arms or money.

Let the People of Israel Remember

The earliest literary commemoration of Zionism’s fallen heroes was a book entitled Yizkor, published in Palestine in 1911 by members of Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion).

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In