How Jews Were Modern

In a 1902 essay on Jewish cultural revival, Ahad Ha’am reflected on the death earlier that year of the Russian Jewish sculptor Mark Antokolsky. He lamented not only the talented artist’s demise but the loss to Jewish culture that his career represented. If Antokolsky had wanted “to create the image of a temperamental and cruel ruler who committed murders every day and terrorized his surroundings,” complained Ahad Ha’am, “but who still had ‘God’ in his heart, and who sinned and repented, sinned and repented,” he could have picked Herod, one of his own people. Why did he have to sculpt a statue of Ivan the Terrible? Did art require him to desert the Jews?

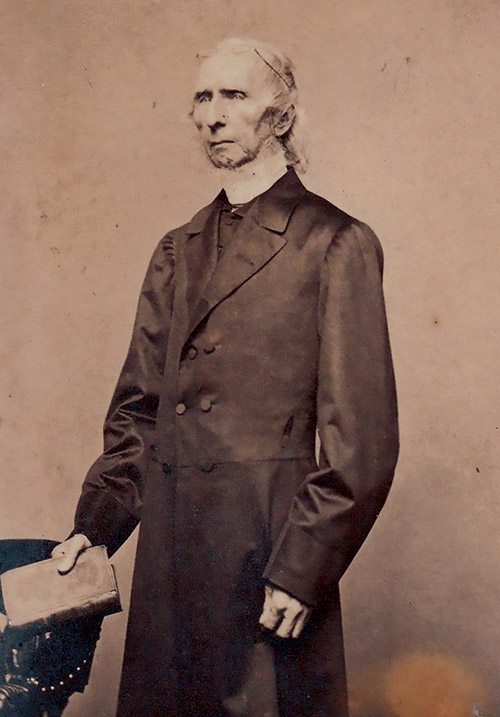

Far from regarding Antokolsky’s depiction of a sixteenth-century tsar as a marker of what Jewish culture has lost, the editor of volume 6 of The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization spotlights it with a full-page illustration. And this is by no means the only way in which Elisheva Carlebach defines Jewish culture far more expansively than Ahad Ha’am ever did. She selects numerous excerpts from the works of Jewish writers that have nothing to do with Jews or Judaism, as well as passages from the works of Jewish-born converts to Christianity, including antisemitic ones.

But Carlebach, the Salo Wittmayer Baron Professor of Jewish History, Culture, and Society at Columbia University, argues that converts merit inclusion “if their work could be seen as having been nourished in some way by their Jewish background.” This is certainly true of Heinrich Heine and Benjamin Disraeli and arguably true of Karl Marx (though Carlebach doesn’t make the argument), each of whom appears in this volume. For unconverted Jews, the bar is much lower. Whatever they produced qualifies as Jewish culture “regardless of whether such expressions contain identifiably Jewish content.”

This latitudinarianism is a guiding principle of this far-ranging anthology of Jewish culture and civilization during a key transitional period. It is, of course, only one part of Posen’s projected ten-volume series covering all of Jewish history, from the biblical era to the present, but it is a crucial one and perhaps the best place to sample the impressive work of an extensive team of outstanding scholars over a long period of time.

Confronting Modernity practically begs comparison with another classic anthology, one whose first (and subsequently revised) edition was published by Oxford more than forty years ago: Paul Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz’s The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History. True, Carlebach’s anthology spans only a bit more than half the years covered by Mendes-Flohr and Reinharz’s work, but the overlap is nonetheless quite extensive. Both books include sizable excerpts from the writings of the central figures in the Jewish Enlightenment and the struggle against it, the leaders in the quest for “emancipation,” and the originators of new denominations of Judaism. While The Jew in the Modern World focuses on programmatic articulations of new religious ideologies or new political goals, this sixth volume of the Posen Library series aims at fuller portrayals of the overall cultural orientations of the individuals it highlights.

Both anthologies include, for instance, passages from Moses Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem (albeit in different translations), in which he spells out his basic understanding of Judaism, but where Mendes-Flohr and Reinharz augment these passages mainly with excerpts from Mendelssohn’s various interventions in the debate over Jewish emancipation, Carlebach focuses on his philosophical writings, both early and late, on the immortality of the soul and G. E. Lessing’s alleged Spinozism. Salomon Maimon, the late eighteenth-century Lithuanian talmudic prodigy turned German philosopher, appears in The Jew in the Modern World as a caustic satirist of the backward Eastern European world from which he emerged. Carlebach shows us this side of Maimon too, but she also gives us a taste of his philosophical writing.

A more deep-seated difference between Confronting Modernity and The Jew in the Modern World lies in their fundamental intentions, which can be seen in their respective treatments of Hasidism. As they note in the introduction to their second edition, Mendes-Flohr and Reinharz sought to elucidate a Jewish modernity that “derives its primary energy . . . from sources other than the sacred authority of Jewish tradition.” Consequently, their anthology does not spend much time with what they call a “movement of popular mysticism.” Despite its title, Confronting Modernity is less concerned with the ideological underpinnings of the modern world than with documenting the Jewish experience from 1750 to 1880. That necessitates, among many other things, a wider sampling of Hasidic sources, from the Ba’al Shem Tov onward.

In the introduction to the first edition of The Jew in the Modern World,Mendes-Flohr and Reinharz justified what might seem to be its “inordinate emphasis on the German and Central European Jewish experience” by stressing that “the dynamic of Jewish modernization” can be seen most clearly if one concentrates on the area where it first occurred. Although they shifted the balance in later editions, their documentary history can still be read as making a strong argument about the fundamental dynamic of Jewish modernity. Carlebach, lacking such an agenda, pays plenty of attention to German and Central European Jewish experience but decenters it. The first selection in her book consists of excerpts from the last will and testament of an early eighteenth-century Sephardi resident of Curaçao, and the last one is from the pen of a late nineteenth-century Egyptian Jewish journalist.

In her introduction, Carlebach assures her readers that when they follow the paths she has traced, they are all bound, no matter how much they already know, “to find new treasures, unexpected juxtapositions, previously unknown texts, and objects that will enrich their understanding of the role Jews played in world culture of the period.” This is no exaggeration.

I was not surprised to find excerpts from both the

notorious defense of slavery published by New York traditionalist rabbi Morris

Jacob Raphall in January 1861 and the immediate, strong denunciation of it by

Baltimore Reform rabbi David Einhorn. But what I had never read before, or even

imagined, was the response to this dispute in an editorial published in Warsaw,

in a Polish Jewish weekly journal in August 1861. David Neufeld (who, among

other things, wrote poetry in both Hebrew and Polish) preferred Einhorn to

Raphall. As embarrassed as Neufeld was, however, by the presence of Jews, whose

“conduct deviates from the religion that binds them to act against bondage,” he

found, rather startlingly, an unexpected silver lining in this cloud: at least

the disagreement between the two rabbis proved that Jews were not united in a

misanthropic

conspiracy.

For us, unbiased judges of the American cause, the events—although we are indignant to the quick at the sight of the downtrodden prestige of sanctity of the Divine Law, which is used and abused by a rabble of impudent empty-hearted people as a pretense to oppress their fellow-creatures—what I am saying is that for us, these sorrowful events are consoling in that, at least, they offer us new proof that confutes the old charge that Jews, dispersed all around the world, form a homogeneous force of personal views that are inimical to all nationalities.

Another unexpected juxtaposition in this volume results from the way Carlebach treats Karl Marx. Her first selection from Marx is a passage from his notorious On the Jewish Question, in which Marx, as she observes, “writes of Jewish ‘hucksterism’ as emblematic of humanity’s universal need to be emancipated from greed and self-interest.” Before turning to a selection from The Communist Manifesto, however, she leaps from Germany to the Ottoman Empire to let us hear “The Cry of the Poor Jews of Izmir,” a protest against the wealthy of their community “who treat the poor as slaves, taking no pity on them and abusing them much more than [we were abused during] our enslavement in Egypt.” Precisely what Carlebach is trying to suggest here isn’t entirely clear, but she certainly provides food for thought.

When I saw the name Sasportas, my first thought was of Jacob Sasportas, the outspoken opponent of Shabbtai Zevi (whose biography by Yaacob Dweck was recently published), but Sasportas died at the end of the seventeenth century, too early to appear in this volume. This volume’s Sasportas was not a Sephardi rabbinic scholar operating in Europe but a Haitian-born Jew of Portuguese descent who divided his time between South Carolina and the Caribbean islands. The selection is from his 1799 “Plan for the Invasion of Jamaica to Emancipate Slaves” and his subsequent interrogation by British colonial authorities. The plan did not come off, and the British quickly put him to death.

The multifarious collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Jewish voices in this Posen volume will be unsettling to those who view the stretch of Jewish history it covers as somehow proceeding from Moses Mendelssohn to Tevye the Milkman with nothing in between but assimilationists and stubborn traditionalists pursuing their separate paths. Volume 6 enables us to see, instead, a vast number of Jews on the move, from one place to another or one ideological stance to another, producing a dazzling array of cultural artifacts in a surprising variety of contexts. They’re not just Ashkenazi, and they’re not just in Europe and North America; they come in vastly different stripes, and they’re all over the place. But how does one put all of this together?

Carlebach doesn’t see it as her task to assist readers in answering this question. In her advice as to “How to Read This Book,” she stresses that the whole collection “focuses on presenting the original works to the English-language reader in the most straightforward manner. Notes and other scholarly apparatus have been kept to a minimum.”

I can understand this decision, but I think that it was perhaps taken a little too far. It would have been better, to begin with, to identify not just the translator of the excerpts but the language from which they were translated. This is rarely stated and not always evident and is something one would like to know, especially in a period of Jewish history when the choice of the language in which an author wrote was fraught with significance.

Sometimes the notes are just too terse. The section on rabbinic and religious thought includes, for instance, an excerpt from an 1840 piece on “Rational Judaism” by an East Prussian preacher and religious teacher who enthusiastically describes a newfangled confirmation ceremony. At a certain point, he tells us, one of the confirmands “makes a simple profession of faith regarding the four articles quoted above,” but that section of the essay is not included. A longer introductory note than the one in the printed version of the volume could tell us what the four articles of faith were (I can guess at three of them).

The introductory notes to selections from the early American Jewish leader Mordecai Manuel Noah and the Sarajevo rabbi Judah Alkalai describe them as Zionists without clearly indicating the very limited sense in which they could be considered to be part of a movement that would not acquire its name while either of them was still alive. A couple of sentences more could have clarified this.

I know that a revision of the text along such lines isn’t likely, but I’m not making these suggestions idly. The whole Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization will be online (though only a few of the ten projected volumes are already there). This is a great boon, both to teachers of Jewish history, trying to keep their required texts inexpensive, and to curious readers of all sorts. And it presents many opportunities for innovative use of the library’s resources (usefully described at www.posenlibrary.com/frontend). While there may have been good reason to scale down the scholarly apparatus in the printed version of volume 6 (and other volumes), I don’t see any reason why changes of the sort I am recommending couldn’t be added to the digital version. They would improve an already invaluable work.

Suggested Reading

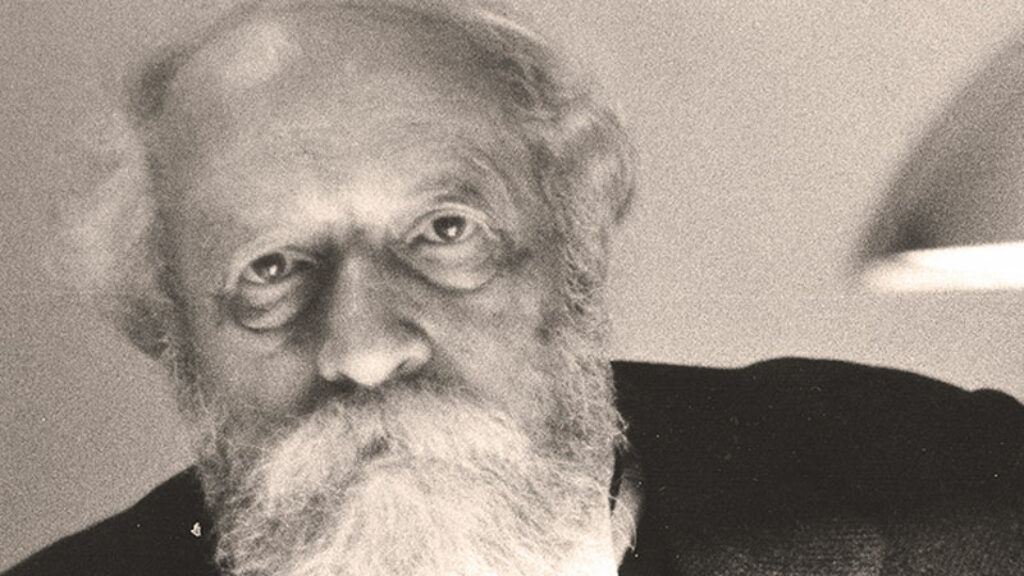

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Tradition and Invention

If Jews were included in early 20th-century discussions of political communities, it was generally concerning their right to preserve their language and culture, along with other minorities, at a time when empires were being dismantled.

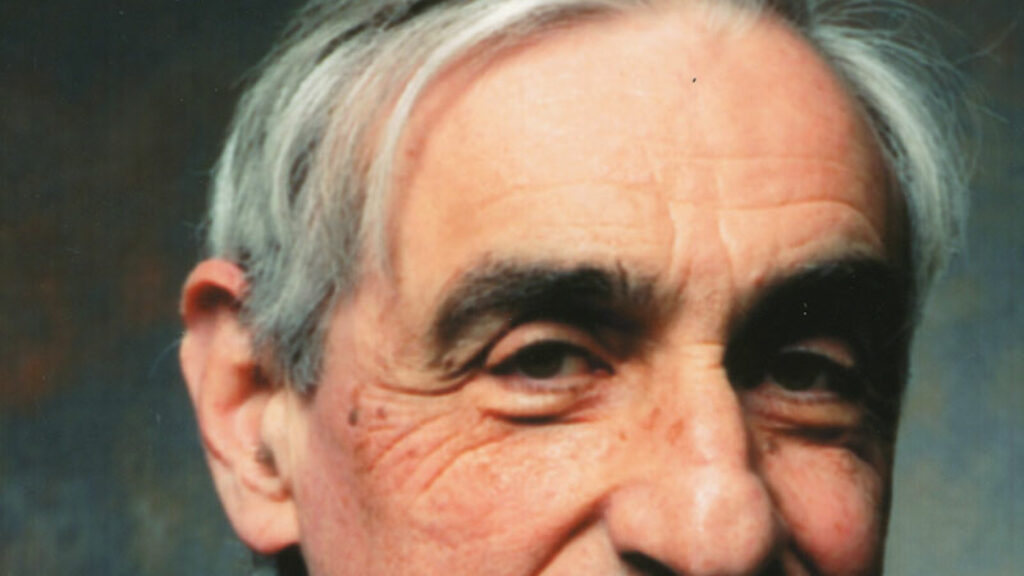

The Gaon of Modernity

Was the Vilna Gaon a great defender of tradition or a radical modernizer?

Confusion and Illusions: 1939

In their new book, Jehuda Reinharz and Yaacov Shavit focus on the efforts of the leaders of a diverse and disunited Jewish people in Europe, the United States, and Palestine to cope with this crisis in the years leading up to World War II.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In