Israel’s TikTok Problem

The House of Representatives just passed a bill, approved from committee with unanimous support, to ban TikTok in the United States unless its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, divests itself of the social media app. Representative Raja Krishnamoorthi of Illinois, the bill’s Democratic cosponsor, says that he and his colleagues are trying to protect Americans from “digital surveillance and influence operations” by the Chinese government, and President Joe Biden indicates he will support the bill. If the legislation musters sixty votes in the Democratic-led senate, then the social media app used by nearly half of Americans may disappear from their phones by the end of the year.

Protecting Americans from TikTok’s political influence would be a gain to Israel’s standing with its most important ally. One month after the October 7 Hamas attack, TikTok videos with hashtags like #freepalestine were watched by Americans about fifty times more than pro-Israel ones. Although the app’s users skew young and hence leftward, their politics probably don’t account for the ratio. Researchers at Rutgers and the Network Contagion Research Institute compared TikTok and Instagram (which has a similar demographic) and found that although Instagram has only twice the number of politically themed posts generally, it had six times more pro-Israel and anti-Hamas posts than TikTok.

Moreover, the company apparently rejected ads from the families of Israeli hostages as too political while accepting ones from pro-Palestinian groups. An internal memo written by Israeli employees complained that “American users are BOMBARDED with paid ads that present the misery of children in Gaza” but are kept from seeing anything similar about Israeli hostages taken by Hamas. Such policies led TikTok’s top lobbyist in Israel, Barak Herscowitz, to resign and prompted President Isaac Herzog to summon European and American TikTok executives for an inconclusive meeting in February.

The TikTok executives expressed concern and promised President Herzog that they had ameliorated the problem and would address it more in the future. But the fact that TikTok is under the influence of America’s main adversary, the Chinese Communist Party, suggests the problem is more than just a wartime burst of digital anti-Zionism. A Pew survey from just before the Gaza war found that a third of eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-old users regularly get news from the platform, and China is demonstrably interested in dividing America’s leaders from its young, whether it is about Israel or anything else.

I recently watched several dozen of the most-viewed TikTok videos related to the Gaza war with pro-Palestinian hashtags (half of which were made in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Pakistan). In one, a Gazan man sits with a large teddy bear next to a multistory wreck, while the melancholy song “Ava,” by the defunct European band FAMY, plays in the background. In another, a pretty woman holds back most of her tears as she makes up her face to look like a Palestinian flag surrounded by small, red hands. In a third, a burly American guy explains that sixty thousand Malaysian children, too young to protest, have “taken to Roblox,” a virtual gamerverse, to demonstrate against Israel’s war in Gaza. Many clips were more graphic, and the only context for any of them is whatever TikTok’s algorithm proffers next: dancing teens, guys putting rubber chickens in their wives’ exhaust pipes, cute toddlers, and, sooner rather than later, more misery from Gaza.

This is not a good way to get news. But in mid-November, there were more pro-Palestinian TikTok videos viewed by Americans than there were total visits to the ten most frequented American news sites. According to an experiment conducted by Generation Lab after the war began, American TikTok users younger than thirty who spent thirty minutes a day on the site were 17 percent more likely than those off the platform to espouse anti-Zionist, antisemitic opinions. TikTok videos about Gaza certainly did not begin young Americans’ disenchantment with Israel, but they almost certainly have exacerbated it.

In one sense, TikTok’s political interventions are less manipulative than the half-truths one finds in newscasts and op-eds. Writers and television personalities tell their audiences things; TikTok’s clips simply show them, but they do it through what may be the most stimulating digital medium there is. When a TikTok dance video appears, you feel tickled. And when you swipe, TikTok’s personal recommendation algorithm will tickle you again. When the clip shows children screaming for their mothers amid the pandemonium of war, any decent person will feel sympathetic grief and righteous solidarity, which are addicting in their own way—and then TikTok will show you more.

Of course, TikTok videos usually don’t mention the actions, reasons, and history preceding the misery and desolation displayed on screen. That is TikTok’s political superpower. The platform bypasses the whole debate about context, in which Israel’s critics and defenders claim that suffering on one side must be interpreted with reference to the plight on the other side. All the viewer sees is the suffering child. And all that many people will take away from that is the desire for whatever is causing the child’s suffering to stop right now.

When President Herzog met with European and American TikTok executives last month, the latter told him that they were “deeply disturbed” by the proliferation of Israel and Jew hatred. The executives claimed that TikTok has disabled more than 160 million fake accounts, many of which distributed anti-Israel and antisemitic videos, and they promised to do more. TikTok has also obscured whatever problem remains by disabling a search engine for popular hashtags like #freepalestine.

Usually, what TikTok shows is determined by an algorithm that feeds the viewer the sorts of videos they linger on and watch many of. But TikTok reserves the right to shape as well as to reflect its viewers’ desires. Last January, on the basis of interviews and company documents, Forbes reported that TikTok’s monitors can push videos they think merit more attention.

The evidence suggests TikTok imported foreign-manufactured anti-Zionism onto the screens of American youth. But why TikTok tried to form and intensify opposition to Israel may have less to do directly with Israel, Hamas, and Gaza than it does with how anti-Israel sentiment is useful to China’s competition with Israel’s American ally.

In 2016, Chinese leader Xi Jinping instructed a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) conference on media to “build flagship external propaganda media outlets with strong international influence.” Five years later, Chinese state media interpreted similar comments of Xi’s by naming TikTok as a means toward the general secretary’s goal of “telling the China story well.”

ByteDance’s chief content editor and his deputy lead the company’s internal CCP cell. In April 2019, ByteDance signed a cooperation agreement with the propaganda department of China’s Ministry of Public Security (the Chinese analogue of the KGB), and TikTok’s treatment of China-sensitive topics just doesn’t make sense independently of the CCP’s interests. The Rutgers study, mentioned above, found that the ratio of posts between Instagram and TikTok on the persecuted Uygher Muslims was 11 to 1; on Tibet, 38 to 1; on Tiananmen Square, 82 to 1; and on the Hong Kong democracy movement, 180 to 1.

China’s interests in the Gaza war are not simply those of Hamas’s patrons in Tehran, even if China is Iran’s most important trading partner and hopes to displace America as the regional power broker. China invests in hundreds of Israeli high-tech companies, does not generally promote Tehran’s view of the Palestinian conflict, and relies on Middle East oil shipments that a larger war could disrupt.

One way to approach China’s strategic interest in American opposition to Israel is through the works of Wang Huning, the fourth-highest ranking member of the ruling Politburo Standing Committee and China’s most powerful intellectual. Trained as a political scientist, Wang has helped direct the CCP’s propaganda and influence operations at least since his elevation by Xi to the committee in 2017 (he spent the previous fifteen years running a powerful party think tank, the Central Policy Research Office).

Wang and Xi embody a culturalist turn in Chinese strategy. A year after Xi became general secretary, the CCP identified “disseminating thought on the cultural front”––rather than improving China’s material strength––“as the most important political task.” Wang’s 1994 article “Cultural Sovereignty and Cultural Expansion” proposed that the end of the Cold War did not end the risk of serious conflict but simply relocated it, from armed to unarmed arenas.

In 1988, Wang spent several months in the United States. The final section of his remarkable philosophical travel memoir, America Against America, notes America’s difficulty cultivating faithful heirs of its traditions:

This generation was made by the past generation, and the next generation will be made by this one, and the end is conceivable. If the transmission of basic knowledge is problematic, how can the basic values and beliefs of society be transmitted? How can they be socialized? This is the greatest challenge . . . to American politics.

Wang identified the “management of knowledge” as the cause of all social conflict, and he identified America’s youth as very badly mismanaged. Graduates of America’s decentralized school system shunned civil society institutions and were left alienated and mistrustful by families far more individualistic than Chinese ones.

Countries sometimes try to divide one another across the political spectrum—Russia’s digital intervention in the 2016 election was such an attempt. Wang’s early tract and his seniority in the CCP suggest another kind of attempt—a hostile bid for the management of what young Americans believe and feel, to impede older Americans from passing on their way of life.

The US-Israel alliance is especially vulnerable to such a strategy. In Congress, and among older voters, support for Israel remains a point of unusual bipartisan agreement. But a Quinnipiac poll from October 17, 2023, found a thirty percentage point gap between voters older than fifty and voters younger than thirty-five on whether America should arm Israel against Hamas. It is difficult to think of another political topic with that degree of intergenerational fracture.

It’s possible that, had TikTok not existed or had been run more benignly, Israel’s position in America would be just marginally better. But margins can damage alliances that would otherwise be merely tense. According to Pew, the share of TikTok viewers who used the platform for news doubled between 2020 and 2023. TikTok’s antagonism toward the Jewish state may be only an instrument of Chinese antagonism toward the United States, but that instrument is getting more dangerous, to Israel and America alike.

Suggested Reading

The Professor and the Con Man

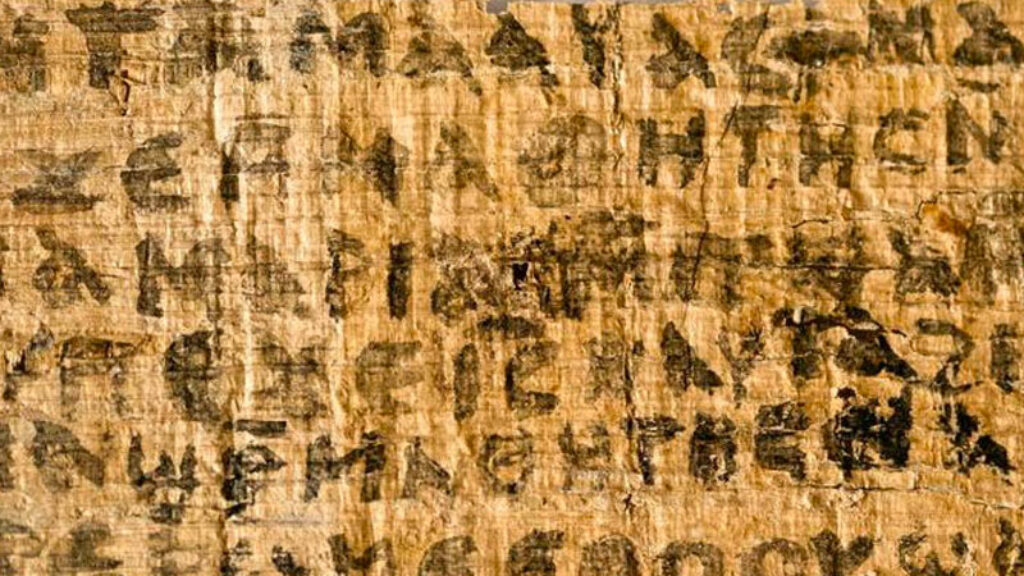

The saga of the papyrus that became famous as the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife began with an email sent to Karen King, a distinguished Harvard professor, in July 2010. The subject line read, simply, “Coptic gnostic gospels in my collection.”

Fleishman Is a Series

Fleishman's real problem is not an acrimonious divorce, but an uninspired adaptation.

Getting Along with the Gentiles

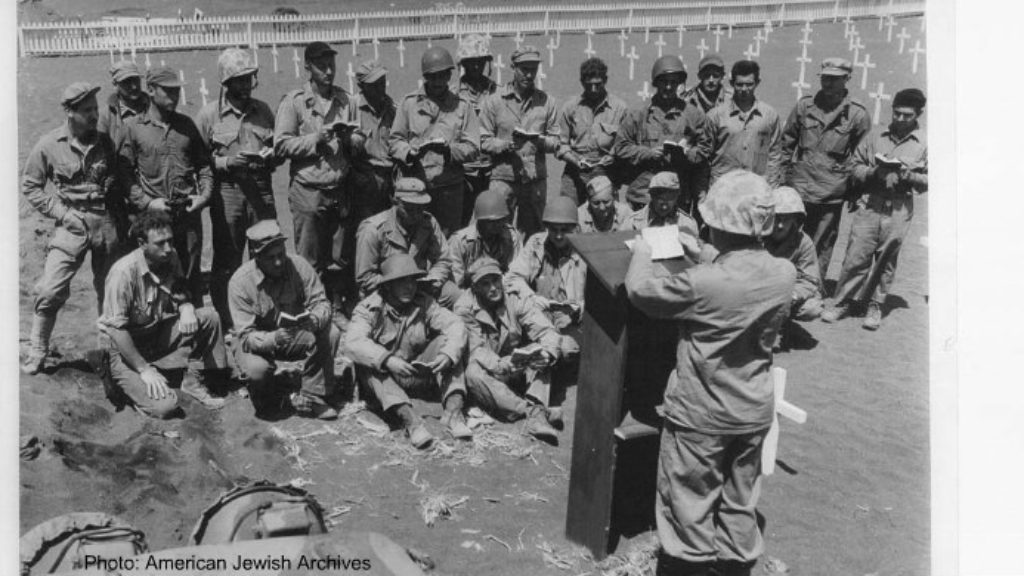

From the Brandeis Book Stall to the sands of Iwo Jima (and halakhic flexibility).

A Lone Soldier

Every year, when Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s memorial day, rolls around, the author thinks of an idealistic college student named Alex Singer who became a lone soldier in the IDF.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In