Getting Along with the Gentiles

One of my favorite used bookstores ever was the Brandeis Book Stall that used to be on Sewall Avenue in Brookline, Massachusetts, not far from the heart of Coolidge Corner. As a graduate student at Brandeis, and for years afterward, I visited it periodically expecting to find unusual bargains. Of all the books I ever picked up there, my favorite was a work on modern liberalism that had been owned by a celebrity. The inscription on the flyleaf, handwritten by the author, a professor at an Ivy League university, read, “To William Safire—a small thing but my own.” It was dated September 4, 1997, the year of the book’s publication. By May 1998, the store had put the volume on sale for a quarter of its list price, and that’s what I paid for it (even though I already owned a copy). I cherish this acquisition as a sharp reminder of the low value that a former Nixon speechwriter and prominent journalist put on the modest work of an academic political theorist.

This wasn’t the kind of book I went looking for, though. I thought of the Brandeis Book Stall mostly as a treasure trove of what seemed to be the remnants of the libraries of aged Jewish scholars, books that were usually available for next to nothing. For the most part, I don’t know whether their former owners had lived in the neighborhood or far away, but I know who had previously owned my copy of Jacob Katz’s The “Shabbes Goy”: Rabbi Roland B. Gittelsohn, the former leader of a nearby Reform congregation. There’s no notation in the book of the date the store acquired it, nor do I remember exactly when I purchased it, but I know that the book was published in 1989, and Gittelsohn died in 1995 at age 85, so he couldn’t have owned it for very long.

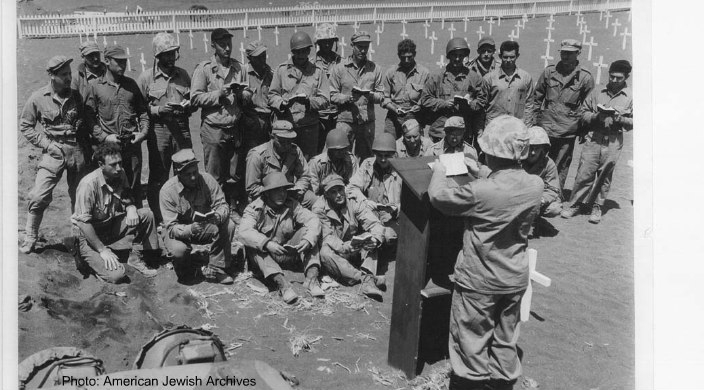

I had heard Rabbi Gittelsohn speak once or twice, but it wasn’t until I read Deborah Dash Moore’s GI Jews that I learned that he had been a chaplain in the U.S. Marines and had been on the scene through the 36-day Battle of Iwo Jima. After the fighting had ended, the division chaplain, a Protestant, invited him to preach at the dedication on the island of the Fifth Marine Division Cemetery. But then two other Protestant clerics protested “the idea of a Jewish chaplain ‘preaching over the graves which were predominantly those of Christians.’” The division chaplain retorted that “the right of the Jewish chaplain to preach such a sermon was precisely one of the things for which we were fighting the war.” But the dissidents were then joined by six Catholic chaplains who strenuously objected, among other things, to a sermon preached by a Jew. Gittelsohn felt that he had no choice but to yield to “the objection of an entire church.” He delivered his eloquent sermon not at the ecumenical memorial service for which it was intended but “at our own little Jewish service.”

Here no man prefers another because of his faith or despises him because of his color. Here there are no quotas of how many from each group are admitted or allowed. Among these men there is no discrimination, no prejudice, no hatred.

The presence of three Protestant chaplains who “were so incensed at what had happened that they boycotted their own service and came to the Jewish one instead” prevented these words from having an entirely hollow ring to them.

Six years older than Gittelsohn, the Hungarian-born Jacob Katz was teaching and doing historical research in Palestine during World War II, but his real academic career didn’t begin until 1945, when he was 41. He more than made up for the late start to his academic career by publishing abundantly in a large variety of fields until he was well into his nineties. Katz was over 80 when he finished the original Hebrew version of The “Shabbes Goy,” one of the last of his major publications in the area of Jewish law. I had my first private and lengthy meeting with him around that time. We sat for several hours (in the home of Alexander Altmann, about whom I promise a future column) going over the first draft of my translation of his short book on the anti-Semitism of Richard Wagner, a volume that he had written, on account of the subject matter and despite strong reservations, in German. Halfway into our session, I tried to clarify a certain point by referring to a Hebrew parallel to one of the English idioms I had employed in my translation. “Ah, you speak Hebrew,” he purred delightedly in Hebrew. From then on, that was the only language in which he would speak to me.

When we were done with the translation, Katz asked me whether I had a solid background in rabbinic literature. I had to confess that I didn’t—not in his terms anyhow. “Too bad,” he said. He was looking for a translator for the book that I ultimately picked up at the Brandeis Book Stall a few years later and very much enjoyed reading.

Why, one might wonder, should there be a book about something like the shabbes goy?Isn’t the whole concept just a silly piece of rabbinic hypocrisy, nothing but a legal ruse to get around problems posed by the divine prohibitions of labor on the Sabbath by having a Gentile do the work for you? How much can there possibly be to say on the subject?

Well, it is a fairly short book—but it is rich in content and should disabuse any of its readers of the idea that the shabbes goy is a bit of a disgrace to Judaism. It is not a wink-wink subversion of God’s law. The main problem the rabbis faced, according to Katz, was one that they believed to be of their own—not God’s—making. “In the original terminology (Shabbat150a), telling a Gentile [to perform creative labor for a Jew on the Sabbath] is a rabbinic prohibition.” It “is not included in the Sabbath observance as laid down in the Torah,” which pertains only to the people of Israel. What they struggled to get out of, when it was necessary, was a trap of their own making.

The subtitle of Katz’s book is A Study in Halakhic Flexibility. His subject is the way in which leading rabbis over the centuries, from ancient Babylonia to 19th-century Russia and Hungary, endeavored both to maintain as much of the traditional law as possible and to accommodate themselves to changing economic, technological, and social circumstances. The main issues they faced concerned not household management but business. When was it permissible and when was it forbidden to derive profit from the Sabbath labor of non-Jewish employees or partners? One of the most interesting chapters in the book describes the predicament of mid-century Hungarian rabbis who sought to govern Jewish behavior in a society in which Sabbath observance was eroding in increasingly large sectors of the Jewish population.

They were faced with a dilemma: Should they aim their decisions at the undecided, making it easier for them to bear the burden of religion under the new conditions? Or should they rule strictly, lest the defection reach those Jews who still remained halakhically observant even at the expense of economic advantage?

Katz, who had obtained his training in rabbinics in traditional yeshivas in Hungary and his PhD in sociology in Germany, had an unsurpassed ability to elucidate rabbinic deliberations of this sort for the layman and to situate them in their specific social contexts. The “Shabbes Goy” is by no means a page-turner, but it offers, like all of Katz’s works, great insight into Jewish history, illuminating often overlooked aspects of the Jews’ relationship with their Gentile neighbors. I wonder what the previous owner of my copy of the book thought of it, after having had his own unique experiences of life as a Reform rabbi dealing with Gentiles under particularly demanding conditions. But I don’t imagine that I will ever know.

Suggested Reading

Leon’s Roar

A new book explores Leon Modena's crusade against Kabbalah in 17th-century Italy.

A Plague on the Shores of the Sea of Galilee

The death of the Great Maggid in December 1772, a week before Hanukkah, was a crucial moment in the early history of Hasidic movement.

Mansions, Museums, and Magen Davids

In building (or rebuilding) grand houses in France and England Jewish immigrants created, brick by brick, edifices within their countries’ histories. Not all would survive World War II.

“In Order that They Didn’t Die Alone”: Remembering Claude Lanzmann

The iconic director of the most critically acclaimed movie about the Holocaust, Shoah, died last week.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In