At the Edge of What?

Visitors to Warsaw’s splendid POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews pass through a section of the core exhibition titled On the Jewish Street. Devoted to the years between 1918 and 1939, a brief interval of Polish independence between two eras of foreign rule, it depicts, according to an accompanying catalog essay, “a modern Jewish world . . . rooted in Poland,” born of the same heady atmosphere of freedom that made “jazz, radio, and movies” mainstays of Jewish cultural life no less than “Mishna or Eyn Yaakov”:

In the two short decades between the rebirth of the Polish Republic in 1918 and the brutal Nazi invasion of 1939, the Jews of interwar Poland created a diverse and lively world of political parties, newspapers, theaters, and schools. This community of 3.3 million Jews faced many challenges. It was torn by political infighting, beset by economic difficulties, and challenged by growing antisemitism. Yet despite these problems, or perhaps because of them, Polish Jewry showed a vitality and resourcefulness unmatched anywhere else in the Jewish world.

“Some historians,” the text proclaims, consider the interval a “golden age.”

Kenneth B. Moss is evidently not among them. Readers of his An Unchosen People, an insightful, incisive, thoroughly documented study of how interwar Polish Jews understood their situation in real time, are likely to see the age as gold-plated at best. He shows that although their “diverse and lively world” may have glittered, Polish Jews saw themselves as overwhelmingly poor, fundamentally unsafe, and deeply uncertain about their future. Their lives were shaped by political currents that were “pervasive, profound, and above all indifferent to what Jews wanted or hoped for.”

Moss focuses on “a growing multitude of [Jewish] skeptics” who, beginning in the late 1920s, cast doubt on the ability of any Jewish political party, ideological movement, cultural organization, or communal agency to generate effective “practical responses . . . to danger and bad fate.” In a tour de force of investigation and erudition, he has uncovered troves of unpublished private correspondence, journals, notes, and memoranda that, taken together with a substantial body of published works, constitute an ongoing conversation in Yiddish, Polish, and Hebrew among some two dozen guiding figures who tried to predict where the increasingly treacherous currents might lead and what Jews might do in response.

A few of Moss’s chosen subjects—social psychologist Max Weinreich; sociologist Jacob Lestschinsky; writers Jakob Appenszlak, Michał Bursztyn, and Chaim Grade—were prominent at the time. Others had more limited public profiles or none at all, like a headmaster of a Yiddish-language school in a provincial town, some local social workers and communal employees, and entrants in competitions for autobiographies by young people held in 1932 and 1934. Although some of them were affiliated with a Jewish ideological movement—Zionist, diaspora nationalist, socialist, or assimilationist—they wrote as individuals with their own idiosyncratic perspectives but came to similar conclusions, and they were far from golden.

Yitzhak Gura, from a Hasidic family in Czyżew, near Białystok, moved from Orthodoxy to Zionism, then to Communism, then to Zionism again, driven, in Moss’s view, “less by ideological attraction and more by darkening assessments about Jewish prospects in Poland.” Avrom Golomb, a widely read Yiddishist educator from Wilno, not only noticed but affirmed such assessments: Polish Jews, he observed, were confronting “a stable, permanent, and chronic uprooting-politics.” Although Golomb remained a committed diaspora nationalist, he spent most of the 1930s in Palestine. This is an example of what Moss calls “vernacular Zionism”—one that looked to that country not so much as a place for living an ideologically correct Jewish life but simply as a safer alternative to an increasingly grim Polish reality.

Palestine was not the sole escape. Gershn Urinsky, the provincial Yiddish-school headmaster, noted in 1934 that many of his students were looking to leave Poland for any open destination. Moss confirms his claim with records showing that between 1932 and 1936, thirty-one of his town’s 183 Jewish high school graduates left the country: thirteen for Palestine, eight each for the United States and Argentina, and two for Cuba.

After analyzing his subjects’ observations in seven detailed, closely interlocking chapters, Moss concludes that a “consuming certainty that worse was coming, [a] sense that Jewish life in the Diaspora might now for the first time truly be mortally threatened, and [a] grim conviction of Jews’ incapacity to do much about either, were by 1933 mainstream outlooks” among Polish Jews. “Mainstream” may require qualification. None of Moss’s guiding figures came from the large segment of Polish Jewry customarily labeled “Orthodox.” Only two were female. The perceptions of the 25 percent or more of Polish Jews unable to make ends meet without charitable assistance appear in the book only as refracted through the eyes of more fortunate observers.

Nevertheless, Moss has amassed and presented more than enough evidence to sustain his primary point: the present-day historical common wisdom reflected, among many other places, in POLIN’s evocation of “vitality and resourcefulness” as hallmarks of a “golden age” for Jews in interwar Poland, “should not lead us to overlook an entire universe of twentieth-century Jewish historical experience and thought.”

Readers may well ask why that universe was ever overlooked to begin with. After all, Poland defined itself from the start as the nation-state of the ethnic Polish community, to which Jews by definition did not belong. Its proclamation of independence in 1918 was accompanied by murderous anti-Jewish violence. When Poland’s first president was elected in 1922, with Jewish support, he was tagged “president for the Jews” and promptly assassinated. The following month the prime minister declared that all political decisions would be made by the “Aryan Christian majority.” The Polish political arena was split largely between parties prepared to bear the presence of Jews as long as they remained in their proper place (as second-class citizens who owed the Polish nation gratitude for its historic tolerance and whose needs and interests must always be subordinate to those of ethnic Poles) and parties who saw no legitimate place for Jews in Poland at all. Few Polish leaders saw any benefit to Poland from the presence of a large Jewish minority, no matter how vital or resourceful.

How could the glitter of “a diverse and lively world of political parties, newspapers, theaters, and schools”—whose impressive dimensions Moss does not question—blind a generation of historians to the fact that by the late 1920s, many Jews were actively seeking to move elsewhere? Indeed, four hundred thousand Jews actually left Poland between 1921 and 1938. Many more would have left if they could. Surely a “golden age” would not have driven masses away. Why, then, has Moss had to remind his peers of something they should have held in mind all along?

The answer has many strands. Moss concentrates on one in particular—how evolving views of the Nazi era intersect with contemporary academic and Jewish politics:

In the decades following the Holocaust, the question of which Jewish movements had understood the situation in Europe and which had not seemed to many to have been answered with terrible clarity [in favor of Zionism]. Even in scholarly circles, few were prepared to take seriously pre-war diasporist, integrationist, or traditionalist convictions that it had been reasonable to hope for a safe and healthy Jewish future in post-imperial Central and Eastern Europe. Today, in the Jewish scholarly world at least, the ground is shifting rapidly in the other direction: a glance at the contents of Jewish studies [courses], journals, and conferences leaves little doubt that scholarship on twentieth-century diaspora Jewry . . . is now dominated . . . by passionate revisionist engagement with pro-diasporic ideologies. . . . It seems obvious that present-day concerns are the driving force behind this quickening shift in common wisdom, and that changing attitudes not only toward nationalism in general but toward the . . . situation in Israel and Palestine . . . are decisive factors.

The introduction to POLIN’s core exhibition fits Moss’s portrayal in part. Although it eschews ideological judgment, it reveals a pronounced determination to avoid foreshadowing impending catastrophe:

We ask visitors to bracket what they know about what happened later. . . . [This] principle

. . . is especially important for the place of the Holocaust in the thousand-year story [of Polish Jewry]. . . . The history of Polish Jews does not start with hate and does not end with genocide. The telling of the story in the exhibition does not drive to the Holocaust as the inevitable endpoint of this thousand-year history. From this perspective, Jews in the Second Polish Republic were not “on the brink of destruction.” . . . It would be a disservice to previous generations to reduce their lives to a prefiguration of genocide.

Moss argues, in effect, that representing those generations as living in “a diverse and lively world of political parties, newspapers, theaters, and schools” without revealing what they actually discussed and debated—namely that they were on the brink of something bad—serves them no better.

After the war, one of Moss’s guides, the sociologist Jacob Lestschinsky, published a collection of articles written between 1927 and 1933, to which he gave the title On the Edge of the Abyss. The articles described various political, economic, and social maladies that Lestschinsky observed among Jews in Poland at the time, including high suicide rates, widespread poverty and malnutrition, scarcity of credit, and a government that heartlessly turned a deaf ear to Jewish pleas for help.

In his introduction, Lestschinsky explained that his title alluded to a piece by the same name that he had published forty-one years earlier, during the wave of pogroms that followed Russia’s 1905 revolution. Russian Jews then, like Polish Jews in the 1920s, lived “on the edge of the abyss,” in his view, because Europe could no longer sustain their large numbers; only mass emigration could save them. The main difference was that Jews who had wanted to leave the Russian Empire to escape impending economic ruin had by and large been able to do so, whereas Jews who wished to leave independent Poland for the same reason found escape exponentially more difficult. That realization, Lestschinsky thought, accounted for a “constant, indwelling panic” he observed among interwar Polish Jews, one that “leads to disbelief in the effectiveness of one’s own ability, through effort and enterprise . . . [to create] a better future.”

His observation involved no foreshadowing. Nor did his volume’s title. The abyss to which it referred was not the Nazi Holocaust but the destruction of livelihood for the East European Jewish masses. Lestschinsky did not believe destruction was inescapable, nor did he share entirely the panic he described. Jews in Poland themselves may not have had the power to alter their situation by themselves, he thought, but they were part of a larger Jewish world that could help them leave the abyss behind. If only Western Jewish organizations would devote greater resources to the task, he suggested, then the pervasive misery engulfing Polish Jewry would abate. Knowing what befell those Jews during a later war (one that neither he nor anyone else foresaw at the time) had not changed his evaluation: his original articles from the 1920s and 1930s reflected “the rhythm of the Jewish struggle” that would later be fought against “the most powerful enemy of all.”

In other words, it is quite possible to portray the situation of interwar Polish Jewry as abysmal without suggesting that it entailed eventual deliberate physical annihilation. Nor is it necessary to posit a golden age to explain creativity, which is sometimes born of desperation. But latter-day fears of Holocaust foreshadowing seem to have made it difficult to imagine any ground between the extremes. Kenneth Moss’s study offers a vital first step toward restoring awareness of a broad range of historical possibilities.

Moss’s analysis misses the mark in one important respect. Where he ascribes the foreboding of Lestschinsky and others to perceptions of anti-Jewish antagonism, their position was more complex. These Polish Jews took for granted that they were under attack, but part of what alarmed them was that they had become less sure of their various means of defense, including international Jewish philanthropy and alliances with other non-Polish ethnic groups within Poland. Lestschinsky wrote that Polish Jews took such aid into account in predicting their prospects and in calculating their risks no less than they did the words of Polish politicians, priests, or peasants. By the time Moss begins his account, after a 1926 coup d’état that installed a centrist authoritarian regime led by Marshal Józef Piłsudski, many Polish Jews already saw themselves in a weaker position than they had been when independent Poland was proclaimed, not because hostile forces were stronger but because their defenses against them had proved ineffective.

As Moss demonstrates convincingly, Jewish fears only deepened on Piłsudski’s watch. The reason, though, may be less that hostility toward Jews increased during his nine-year rule (which it did) than that, as Lestschinsky argued, his regime chose not to expend the political capital required to check that hostility. In any event, much Polish Jewish political thinking before, during, and after the Piłsudski years was concerned not only with assessing the risks posed by possible anti-Jewish offensives but with developing new defenses against them.

Moss gives the defensive side of the equation short shrift, placing nearly the full burden of Polish Jewry’s predicament on the increasingly vociferous “antisemitic ethnonationalism of the Right.” That omission is unfortunate, for Jewish safety always depends on much more than the hatred or benevolence of others. The history of interwar Polish Jewry offers fertile ground for exploring the full range of factors that have governed Jewish security past and present.

Suggested Reading

Law, Justice, and Memory in Poland

Under the Law and Justice Party, Poland has just criminalized the life stories of its Jewish survivors. Here’s why.

A Brand Rescued from the Fire

Leon Chameides has painstakingly collected his father’s writings from the fateful years of 1930s Polish Jewry, before the break-up of his family and the collapse of Jewish life in Nazi Europe.

Bind Them as a Sign: A Photo Essay

A Hasidic-owned, bicycle-powered tefillin factory in Krakow, Poland.

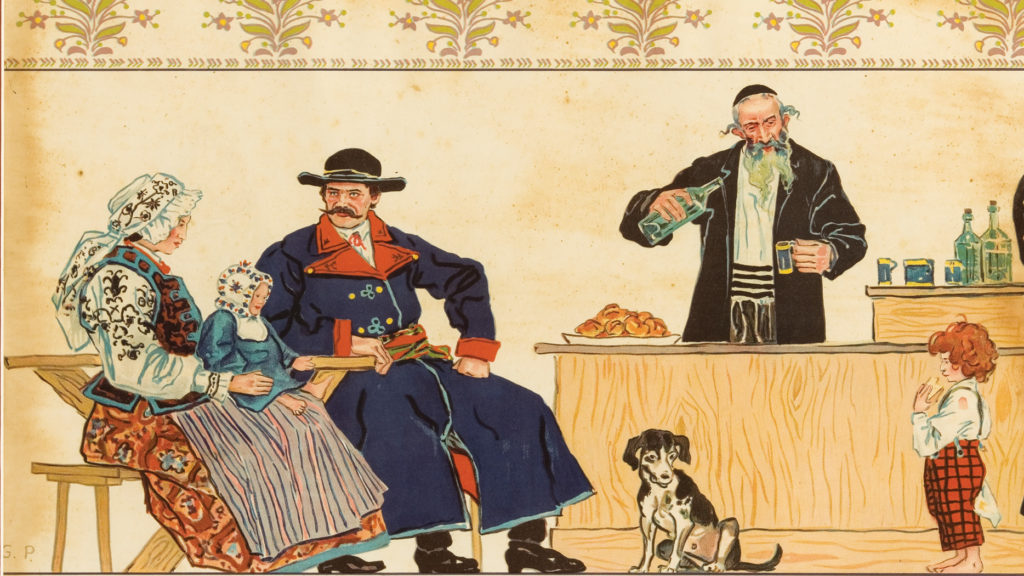

Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

Jewish-run taverns—rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes—served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews, as a new book by Glenn Dynner shows.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In