A Brand Rescued from the Fire

As the skies began to darken over Nazi Germany, Martin Buber, who remained in the country to teach and support his community until 1938, was one of the first to give voice to the suffering of Jewish children. Writing in the main Jewish paper, the Jüdische Rundschau, in 1933, Buber appealed to parents and educators to address the special needs of the child:

The children see what is happening and are silent, but at night they groan in their dreams, awake, stare into darkness. The world has become unsafe . . . the soul no longer finds its way into the world. It becomes hardened and callous . . . Parents, teachers, how can this be avoided?

Buber called upon parents and teachers to do all in their power to preserve some semblance of stability in the lives of the children under their care. But what is the responsibility of adults when this sacred task is no longer possible, when the world has become unsafe for children and parents alike? While most Jewish parents under the Nazis had no control over the ultimate fate of their children, some were confronted with the painful choice of whether to entrust their children’s lives to Gentile neighbors (those few souls, relatively speaking, willing to risk their own lives to save others), with the real likelihood that they would never see them again. The trauma of the child was inextricably linked with that of the parents, at times forced to choose between one form of unspeakable sacrifice and another.

On the Edge of the Abyss: A Polish Rabbi Speaks to His Community on the Eve of the Shoah is the product of two men, a father and son, working independently of each other and separated by some 80 years. The father, Rabbi Kalman Chameides, did not survive the war. Had he not had the foresight and courage to hide his two sons in a monastery, his children would almost certainly have shared his fate. Eight decades later, the younger son, Leon, is still haunted by memories of the day his father surreptitiously brought him, at the age of seven, to the monastery and left him there, without a word of explanation, in the care of the metropolitan of the Uniate church, Andrey Sheptytsky. The silence of his father’s agony will never be filled, but Leon Chameides has now painstakingly collected his father’s writings from the fateful years of 1930s Polish Jewry, before the break-up of his family and the collapse of Jewish life in Nazi Europe.

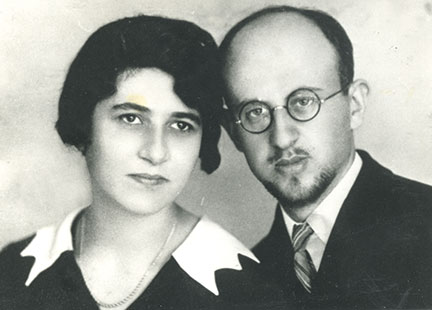

On the Edge of the Abyss consists of 75 essays in German and Polish written by Kalman Chameides between 1932 and 1936 for his community of Katowice, Poland. The essays were cut short when Kalman was tapped to serve as a Jewish chaplain in the Polish army and was forced to divide his rabbinical duties between Katowice and Będzin prior to the German invasion of September 1939. Fleeing German forces, the Chameides family took refuge in eastern Poland (then under Russian control) before it, too, was conquered by the Germans in the summer of 1941. Shortly after Kalman and his wife, Gertrude, successfully hid their two sons along with other Jewish children disguised as Christian orphans, they were transferred to the Lwów Ghetto, where they and nearly all of those who were not evacuated to concentration camps perished.

Leon Chameides, who was brought to England and then the United States after the war, went on to become founding director of pediatric cardiology at Hartford Hospital and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Connecticut. In his later years, he began to reconstruct his family’s story, which resulted in his earlier book Strangers in Many Lands: The Story of a Jewish Family in Turbulent Times. This, in turn, led to On the Edge of the Abyss. (As with many family histories and memoirs from these years, both books are self-published.)

These essays, written in a soaring and often prophetic pitch, are a rare testimony of Orthodox rabbinic leadership during these critical years and, not surprisingly, have much to say on the state of Europe, the future of its Jews, and (especially poignantly) the prospects of its children. In an essay from August 1935, entitled “Jewish Children as Martyrs,” Rabbi Chameides urged his community to prepare their children for the deep-seated hatred that soon awaited them and for which they would have to pay a heavy price in their own lives.

Today, a Jewish child sees a world of enemies confronting him like once little David faced the giant, Goliath. His martyrdom begins in his earliest school days, where the first principles of racial prejudice are taught. He knows nothing of golden childish dreams since the childhood of a Jewish child is filled with great anxiety about the future. Jewish children have hardly become conscious of life and joy, when they realize that they are surrounded by enemies; encircled by hatred and distrust . . . Today, the Caesar is no longer trying to win over Jewish children’s hearts. He no longer tries to convert them to his own faith. He wants to annihilate them. He knows no pity… And because of this, Jewish children must once again become heroes . . . Teach them to bear humiliation with pride; to accept denigration in peace; and teach them, in suffering, never to deny; in an assault from hostile forces, never to lose hope . . .

The Jewish children of 1930s Europe were indeed to bear a heavy burden for the hatred propagated by inveterate enemies of the Jewish people. If Israel’s foes in a former age sought their souls for conversion, the Caesar of the day wanted nothing less than their physical destruction. Yet still the child is taught to never lose hope, to never give up. As we know, Chameides himself, some seven years later, responded to the very real threat of physical destruction with the determination to save as many children as possible from this fate. But this, too, came with the terrible sacrifice of separation.

When Chameides wrote of Jewish martyrdom in 1935, it is tempting to read this as a prescient vision of the fate of European Jewry. There was, of course, no way for anyone to know what lay ahead, and certainly no one could have dreamed of the scale of mass murder that was in store. The historian David Engel has pointed out to me that the word for physical destruction (Vernichtung) used by Chameides took on the connotation of “annihilation” as a direct outcome of the Holocaust. Nonetheless, Chameides’ vision of the future of European Jewry in 1935—framed in terms of the future martyrdom of Jewish children—was indeed prescient and exceedingly dark. That same year, he wrote of the “scientifically embellished” anti-Semitism prevalent in Germany: “First, they proclaim a sentence of death for our spirit in order then, with a clear conscience, to bury our physical existence.”

Chameides had sounded a similar note of foreboding two years earlier, in September of 1933, when he issued a lament over the current crisis facing German Jewry and its inevitable decline. The exile (or golus, as he put it) of German Jewry had already begun:

Discharged from employment, deprived of all legal rights, their dignity humiliated and disgraced, thousands of our brothers in Germany have had to flee their native country, to which they pledged their loyalty and dedicated their lives, and to wander like vagabonds seeking refuge in neighboring hospitable lands or in our new national home. . . . ‘They, that were brought up in scarlet, embrace dunghills’ (Lamentations 4:5)—not long ago German Jews were the leaders of world Jewry, enriching the treasure of their nation with their material and spiritual wealth. Today they stand on the edge of a precipice, holding a wanderer’s staff. That is the golus of our times!

Chameides’ assessment of German Jewry eerily echoes that voiced by Rabbi Leo Baeck, the one-time believer in German-Jewish symbiosis and the beloved pastor of Theresienstadt, who famously declared in September 1933, that “the thousand-year history of German Jewry is at an end.” It bears repeating that neither Baeck nor Chameides could have imagined the extent of the nightmare that was soon to unfold in Germany and Poland. Yet both (and, we must imagine, they were not alone) were seemingly convinced that the end of a viable Jewish life on German soil was drawing inexorably closer.

If German Jews were reduced to vagabonds and refugees, there was still a bright spot, as Chameides saw it. Many found the refuge they sought in “our new national home,” the envisioned Jewish state in the Land of Israel, of which Chameides wrote with profound optimism. The contrast between this optimism and his prognosis for European Jewry is on full view in several of these essays. In one, Chameides writes of the twin plagues of anti-Semitism and poverty afflicting the Jews of Europe. “Our youth is wasting away. Hope for a better future is melting away. Our only joy is blooming in the East . . . Let us believe and work for it!” In another, entitled “Hero and Martyr,” Chameides writes that the only heroic activity for which Jews may aspire is “in areas of Jewish productivity connected with the restoration of the Jewish national home,” whereas in Europe, “we have been and, unfortunately, continue for the time being to be martyrs. Here, we must be prepared to suffer for our Judaism.”

There is, surprisingly, one prominent exception to Chameides’ bleak assessment of a Jewish future in Europe: his native Poland. His relative optimism for the future of Poland was evident in an essay from September 1933, when he expressed his gratitude for Polish support of Jews in international affairs. This was probably a nod to official Polish approval of the Bernheim Petition in the League of Nations during the spring and summer of 1933, a petition challenging Germany to reverse its discriminatory policies toward Jews in German Upper Silesia in accordance with the Geneva Convention of 1922. Chameides did not let even such modest support go without proper recognition. Next to England and France, he wrote, “Poland deserves the highest praise among civilized nations for defending our rights in the international arena . . . The only relief and joy amidst the sadness is the fact that we are not alone; that in our misery we have friends…”

His outspoken defense of the Polish state won Chameides admirers within the Polish establishment. Sought out by government officials to lend his support for the strengthening of national defense, Chameides spoke forcefully in the name of all Polish citizens. “Who among us,” he asked in May of 1934, “does not sense that peace in Europe rests on a flimsy foundation? That any day now, we may be facing a new world catastrophe…? Our efforts are directed solely at fortifying and consolidating our State.” Chameides warned that, in the event that peace is unattainable, “we cannot imagine the magnitude of the devastation and destruction; of the suffering and catastrophes, which such a war would cause with today’s technical development in modern warfare . . . We must prepare ourselves, become educated, and adapt ourselves for this terrible battle.” The uncanny realism of these predictions echoes Chameides’ appeal—on the 15th anniversary of the founding of the Second Polish Republic—for Jews and Poles to work together against “a common enemy who lies in wait for our destruction,” the Nazi racist venom that contains “the spark of a new, bloody world war.”

Yet it is entirely possible that Chameides’ plea for common cause in defense of the Polish homeland was intended more to convince Polish authorities of the loyalty of the Jews than the other way around. The Jews of Poland had reason to be concerned. On January 26, 1934, war minister Jósef Piłsudski led Poland to sign a non-aggression pact with Germany. At the same time, sporadic physical assaults against Jews on the street and targeted attacks on Jewish shops and homes that had occurred since the rise of the student-led Green League in 1931 intensified with increased frequency by the summer of 1934. On June 7, four prominent Polish rabbis made a formal appeal to Cardinal Kakowski in Warsaw, “in the name of the Rabbis and Jews of this illustrious Republic,” to exert his moral authority in suppression of violence against innocent Jews. The cardinal viewed the violence as “regrettable” but inevitable given the role of Jews in the corruption of religion and morals in the country.

In the midst of this period of Jewish anxiety, a representative acting on behalf of the British Joint Foreign Committee, the American Jewish Committee, and the Joint Distribution Committee visited Warsaw to meet with local Jews and to beseech the Polish government to protect its Jewish minority, as required by the Minorities Protection Treaty it had signed in 1919. Instead, Poland formally repudiated the treaty, leaving Polish Jewry in a precarious position. Rabbi Chameides’ essays reflect the growing apprehension on the Jewish street while maintaining a determined optimism in the ultimate triumph of humanity (and Poland). In November 1933, he could still give voice to the centuries-old Jewish belief in historic Polish tolerance: “Poland remembers its old traditions. Poland, the noble and chivalrous, has remained faithful to the principles of its men of vision, to the ideals of its tolerant kings.” By September of 1934, however, he found himself looking back on the events of the previous year with deep concern:

Ein rega bli pega—there is not a moment without another misfortune. Our destiny is spinning like a vortex, and the earth is shaking under our feet . . . But even more painful and tormenting than the constant blows and wounds, which Providence has not denied us, is the uncertainty and instability of our circumstances; our concern and feelings of insecurity about the future . . . Who could possibly recount all the incidents of humiliation of Jewish honor, of disgrace and slander of the Jewish name, or of denigration of the Jewish faith?

Yet in the midst of the mob violence, the racist propaganda, the religious vilification, now compounded by political instability—Chameides reminded his congregants of the Jewish duty to see God’s goodness even in misfortune, as when we hear “of individuals who, with heroic generosity, endangered their own lives in order to help and save others; of feelings of partnership and brotherhood, which enveloped everyone; of instances when Christians were saved by Jews and Jews by Christians. Tragically, this misfortune has destroyed human life and property. But it has saved our faith in man.” In Chameides’ abiding faith in a common humanity among fellow Poles that rises above “artificial divisions” and religious creed, one hears echoes of Emanuel Ringelblum, who, as late as June 1942, viewed the frequent occasions when Poles and Jews continued to interact in spite of the Warsaw Ghetto barrier as “a symbol of the unbreakable commonality of the Polish-Jewish fate.”

To those who are quick to forget the loyalty of Jewish citizens to their adopted countries, Chameides recalled the magnanimity of the biblical patriarchs toward their neighbors. “May we, despite this ingratitude, always feel the blissful feeling which permeated Joseph’s whole being . . . May the words, which God spoke to our patriarch, Abraham, always light our way and, despite disappointments, always keep human goodness and a willingness to help alive in us: ‘Be a blessing—and all the family of man shall be blessed because of you.’” The commitment to human decency in the face of indignity was, for Chameides, the enduring message of Judaism in all places and in all times. In the broken tablets of the law that the Israelites carried with them in the wilderness, Chameides saw the shards of human ideals crushed under the weight of barbarism yet continuing to shine in their brokenness. “We have never undermined our ideals when, abandoned and alone, they have been smashed against the cliffs of life. On the contrary, we have collected the remnants and carried them with us.” The smallest act of decency, surrounded by so much pain, could be imbued with heroic dignity. “In such a difficult time,” he wrote in July 1935, “we turn our gaze into the past. We remember our holy ones, our heroes and martyrs . . . Let their lives be a model for us!” In describing the suffering of his community within the context of its national destiny, Chameides constructed a fragile but real spiritual barrier against the madness raging outside.

Kalman Chameides died of typhus in the Lwów Ghetto on December 25, 1942. According to the testimony of a survivor, Gertrude carried her husband’s body to the cemetery on her back and marked the grave to ensure the plot could be identified after the war. Despite her heroic efforts, his family has not been able to locate it.

According to a tradition recorded in the Jerusalem Talmud, one need not construct a monument at the grave of the righteous, for “their words are their remembrance.” In restoring his father’s testimony and teachings to their rightful place, Leon Chameides has more than fulfilled his duty as a son. His father’s words are a powerful repudiation of despair in favor of a magnanimous affirmation of life and human dignity. In the words of the prophet Zechariah, they are a precious brand rescued from the fire.

Suggested Reading

Getting Out from Under: The Philip Roth Story

“I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting,” Philip Roth told his biographer. Has he?

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

The Mocker and the Makhers

Herman Mankiewicz's life wasn't all drunken bets and witty repartee. After all, he wrote Citizen Kane. Life in 1930s "Eretz Demille."

A Rejoinder

I didn’t know that there was anyone left in the academic world who held as simplistic view of history as the one that Eric Alterman espouses in his response to my review (“Context and Content,” Winter 2023). The historian’s job, he says, “is not to voice disapproval or approval” of anything. Consequently, he endorses “nothing and no one in this…

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In