The Big Schlep

Theodor Adorno said there could be no poetry after Auschwitz, but he didn’t say anything about buddy movies, which, I guess, is an argument in favor of A Real Pain. The film follows two cousins, anxious, fussy David (Jesse Eisenberg, who wrote and directed the film) and the appealing but erratic Benji (Kieran Culkin in a lucid, sincere performance), who go on a heritage tour of Jewish Poland after the death of their grandmother, a Holocaust survivor.

The cousins’ trip will take them to monuments to Jewish and Polish resistance, an old Jewish cemetery, a kitschy kosher-style restaurant, cities where Ashkenazi Jewish culture once thrived, and Majdanek, where it was brutally and systematically extinguished. As a coda to the organized trip, they will visit the house their grandmother grew up in.

David has a wife, Priya, and young child, Abe, in Brooklyn, while Benji, unemployed and uncoupled, smokes too much weed and cannot cope with the pain of everyday life. David swallows his with OCD medication, jogs, meditates, and has a real job, selling digital ad banners (which may account for his atheism). Although he presents as an affable stoner, Benji is a self-destructive mess. This trip, they both hope, will allow them to learn something about their grandmother’s life (over the film’s course, an image forms of someone tough and caustic—a survivor) and perhaps reconnect with one another.

David could be a grown-up version of the emotionally impacted character Eisenberg played in Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale or the son of one of Woody Allen’s more existentially resigned characters. He’s frustrated by Benji but envies his cousin’s ability to connect with others, and the film’s focus gradually cedes to the charismatic, unstable Benji, as the supporting characters, almost to a person, end up thanking him for his insights.

Eisenberg keeps the film short, fast moving, and in an insistently minor key, like the tasteful Chopin (played by pianist Tzvi Erez) that dominates the soundtrack. The characters are skeptical of religion, but the movie is devout about the beats of the buddy and road trip genres. It starts and ends at the airport and focuses on the Poland tour led by James (Will Sharpe, who is excellent), a bookish, non-Jewish, Oxford-educated British tour guide “obsessed with Jewish history,” along with four others looking for meaning.

Eisenberg is good at the stilted nature of tour groups. The other members include Jennifer Grey’s sparky LA divorcee, a retired suburban couple who don’t make much of an impression, and Eloge, a survivor of the Rwandan massacre. Eloge converted to Judaism after feeling a kinship with the Jewish community who helped him when he made it to Canada. This is admittedly flattering to a Jewish audience, but Kurt Egyiawan gives a still and affecting performance, and Eloge is the film’s only Jewish character who embraces or even seems conversant with Judaism. In one of the film’s funnier moments, he tells the fidgety David he would benefit from keeping Shabbat. (“Everyone would benefit, or specifically me?” “Specifically you.”)

David and Benji are a classic odd couple, a little bit like Steve Martin and John Candy in Planes, Trains and Automobiles, except this time the trains are Polish and the characters are Jewish, which admittedly gives it all a different valence. But Eisenberg likes to keep things moving; whenever the story threatens to branch out or go in a more anarchic direction, as when David oversleeps on a train and the cousins end up in Krasnik by mistake (two Jews lost in the Polish woods? That sounds interesting), the course is always corrected. If it’s Tuesday, this must be Lublin.

So the very American David and Benji walk through lush Polish parks and muse that, if not for the Holocaust, they might be from here. But this doesn’t strike them as a nightmare or make them wonder what might have taken place in places like that pretty green park earlier in Poland’s history. And this is the film’s real problem: It does not, or cannot, confront the actual, tortured history of Jews in Poland or the issue of Polish complicity in the Holocaust.

Lublin, James says over some pretty establishing shots, was like the “Jewish Oxford,” though that may say more about James than it does about the city. The actual movements that gripped Polish Jewry between the two world wars, like Zionism, Socialism, and Hasidism, are not ones you’d associate with a contented, unmolested population. The film’s best sequence has James telling the group that if you look closely enough in Lublin, you can see traces of its Jewish past—synagogues, yeshivas, cheders, and so on—but the visuals he’s narrating show us only the nondescript Polish buildings that have completely obscured that past. In an early set piece at a memorial to Polish heroism, the joke is only about the characters’ American gaucheness and David’s inability to let loose and follow Benji in posing goofily alongside statues of Polish soldiers—not about Poland erecting monuments to its own bravery.

In the Jewish cemetery, Benji tells the tour guide that he natters on too much about history at the expense of their connecting with “real Polish people.” He seems to think that before the Nazis arrived, his grandmother was herself such a person, though I have met very few survivors (including my own grandparents) who would agree—let alone most of the Poles they lived alongside. The film gives only the barest of hints that the social and historical reality was more complicated than that.

There is a moment when Benji rails against “antisemitic pricks” at the Jewish-themed restaurant because they can’t hear each other over the playing of “Hava Nagila,” but James quickly reassures him the owners are Jewish; it’s just that the music is a bit kitschy. In reality, Poles now dress up as “Jews” with fake payos to serve soup to tourists in Kazimierz, the old Jewish quarter of Krakow. You don’t need to be the Seer of Lublin to wonder if the film treats these matters so gingerly because it was partly financed by the Polish Film Institute. The institute is an arm of the Polish government, which in 2018 outlawed claims that Poles or Poland were in any way responsible for the Holocaust as defamation.

Independent filmmaking is hard and full of such compromises. And there are advantages to the verisimilitude of filming in Poland: The Majdanek sequence is austere and moving, the music finally dropping out of the soundtrack as trees wave in the wind while the group’s bus drives off. Afterward, when David and Benji smoke pot together on the hotel rooftop, they see the lights of the camp in the (not too far) distance and feel the uncanniness of being in a European city so close to the site of so much industrial murder. Is Eisenberg deliberately subverting the idea that the Holocaust merely happened to Poland rather than also because of so many of its citizens’ active collaboration in this scene? It’s hard to say, but the film generally depicts Poland as a very nice place with some difficult history that happened to it. Indeed, the film’s one-liners take more shots at Jewish culture than Polish. “Whenever I see a Hasidic guy on the street, I always just think there but for the grace of no God go I,” David quips. The nightmare isn’t a Polish pitchfork but having to wear a kapote.

At the film’s climax, David and Benji place stones on the doorstep of their grandmother’s nondescript house, as they had on the graves in the Jewish cemetery earlier in the film. An old Polish man across the way (crotchety but unthreatening) and his son (halting and respectful) explain to them that they must not do this, because the old woman who lives there now could trip and fall.

Neither Benji nor David wonders how this particular old lady came to be living in their grandmother’s house. My grandmother, who made it back to her family’s house as one of its few survivors, knocked on its door and found it opened by a former neighbor who had taken possession of it. She sensed that if she pressed her case the neighbor would kill her. Such stories were common after the war, and the restitution of Jewish property in Poland remains a live legal and diplomatic issue. But now we are given two affably clueless Americans who are taught a lesson about civility from their grandmother’s would-be Polish neighbors.

While it was nice to see David and Benji hug at the end, by this point the Chopin on the soundtrack had come to feel like Pole-washing. For a film about emotional inheritance and the gap between personal and ancestral pain, A Real Pain seems determined not to dig too deeply. It feels warmly toward its solipsistic characters, but the film’s warmth and self-effacement come at the expense of any larger point. It doesn’t just depict its characters who have a limited understanding of the past; it endorses it.

Eisenberg, in interviews, has described the film as a “love letter to Poland.” Well, as Woody Allen might say, the heart wants what the heart wants. I understand how many Jewish customs and attitudes come from the Jewish people’s time in Ashkenaz. And I myself loved my time (and even felt at home) in Munich, where my mother was born after the war—but I also felt the obvious historical complication of that affection, an ambivalence the film might have expressed or explored. My grandparents talked about the beauty of Polish forests, but this did not negate the brutality of much of the local population or what sometimes happened in those forests.

For real pain (and humor), one could do worse than spending time with the survivors who are still with us. A friend’s grandmother who was served cold soup at a family Seder asked, “For this I survived Auschwitz?”

Suggested Reading

A Serious Comedy

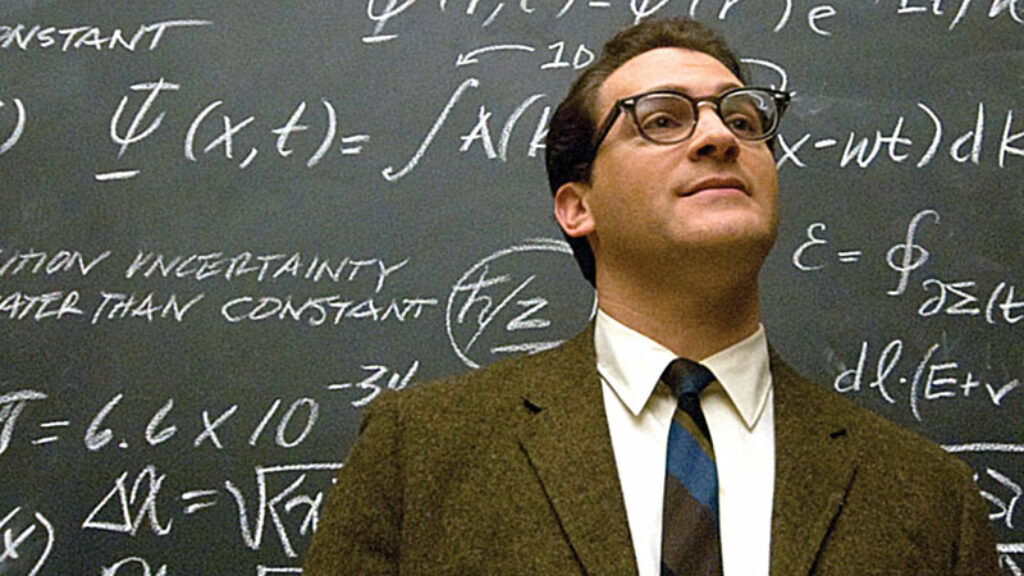

In A Serious Man, the Coen Brothers found a way to address the realest of subjects—their own childhood, their own sense of Judaism—without sacrificing their style; they “grew up” without losing their humor.

Fleishman Is a Series

Fleishman's real problem is not an acrimonious divorce, but an uninspired adaptation.

Include Me Out

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures seems to have had one goal for its exhibit about the Jews who created Hollywood: make the angry letters stop.

The Body in Verse

Examining the lost art of the poetic physician. "Know that it is not in your ability to fulfill them / To God alone belongs this power."

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In