The Golem of Montreal

In one of the most bizarre, yet deadly serious rulings (about the undead) in the vast literature of rabbinic responsa (She’elot u-Teshuvot), the renowned seventeenth-century sage of Amsterdam and London, Hakham Zvi Ashkenazi, was asked whether one may count a golemfor a minyan. Although himself wary of Kabbalah’s dangers—a relentless Sabbatean-heresy hunter and outspoken opponent of the messianic mysticism of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato—the Hakham Zvi(so named after the title of his collection of response) decided that, in this respect at least, golem lives do not matter:

I was unsure regarding the [status of] a human created using the Sefer Yetzirah, such as the one mentioned in [Tractate] Sanhedrin [65b], “Rava created gavra [a man],” as well as the later testimony that my grandfather, the Gaon Elijah of Chelm [Rabbi Eliyahu Baal Shem, 1550–1583] counted the Golem he created towards a minyan for those things requiring ten [men], for example Kaddish and Kedushah. . . . [However,] we find that Rav Zeira . . . later ordered [Rava’s Golem] to be killed. Now, if we assume that the Golem is counted towards the ten needed for matters of Kedusha, R. Zeira would certainly never have killed it . . . which proves that [the Golem] cannot be counted towards the ten needed for all holy matters. So, at least, it seems to me.

Given the almost innumerable popular tales about the Golem published in about a dozen languages, as well as the stage and film productions of the Yiddish play Der Goylem, the Hakham Zvi’s ruling might today appear to suffer from a glaring historical oversight. While he refers to his own grandfather’s golem of Chelm, he fails to mention the most notorious—indeed, the dark prince—of all golems: the one widely believed to have been fashioned by the Maharal of Prague, Rabbi Judah Loew, in the previous century. There is a simple reason for this omission. The sixteenth-century “Golem of Prague,” the giant human-shaped lump of clay who was mystically activated by the Maharal every week to defend the Jews and then deactivated every Shabbat, was not really created until the early twentieth century—and even then only on paper, in a book of tales culled from imaginary manuscripts by the most prolific rabbinic plagiarizer of the modern era.

Ira Robinson’s new biography paints a rich and extensively researched portrait of Yudel Rosenberg, the deeply learned but highly eccentric chief rabbi of Montreal, who moonlighted as a faith healer, magical amulet salesman, oracle, halakhic innovator, Hasidic storyteller, and the most aggressively enterprising kosher chicken slaughterhouse supervisor in Canadian Jewish history.

Yudel Rosenberg was born into a Hasidic family in the small Polish shtetl of Skaryszew and held varied rabbinic posts in Tarłów, Warsaw, Lublin, Lodz, and Toronto until he crowned himself as the chief rabbi of Montreal. This was much to the consternation of the communally appointed Litvak chief rabbi Zvi Hirsh Cohen, with whom Rosenberg fiercely feuded for dominance in certifying the city’s kosher slaughterhouses. The book’s biographical narrative is followed by insightful chapters focusing respectively on Rosenberg’s unique approach to rabbinical jurisprudence and inimitable skills as a storyteller, preacher, healer, and kabbalist.

Although he was an indefatigable entrepreneur, scholar, preacher, healer, kabbalist, and basement inventor, it was Rosenberg’s story of the Maharal’s golem, Sefer Nifla’ot Maharal mi-Prag ‘im ha-Golem (The Wonders of Rabbi Loewe of Prague and His Golem), that earned him worldwide fame. Rosenberg attributed the manuscript to Isaac Katz, the Maharal’s son-in-law, and claimed that it was discovered in the Imperial Library of Metz. The book was published inWarsaw in 1909 and has been reprinted at least ten times since, most recently in 2013. Less than two years later, Rosenberg also published the wondrous tales of Elijah the Prophet, which he composed in both Hebrew and Yiddish, followed by his healing manual, Sefer Rafa’el ha-Malach, along with its Yiddish version, Sefer Segules u-Refu’es. Only quite recently, long after having become a classic of Yiddish, Hebrew, English, German, and Czech literature, was the famous story of the golem of Prague revealed to be Rosenberg’s invention, perhaps loosely based on some nineteenth-century legends. The “Imperial Library of Metz,” which Rosenberg vaguely located in the European land of “Lotharingia” and that he claimed as the source of so many of his archival discoveries, never existed.

The magnitude of Nifla’ot Maharal’s influence is such that the late scholar of both Kabbalah and Modern Hebrew literature Joseph Dan deemed it “the most important twentieth-century contribution of Hebrew literature to world literature.” Still, the work that has elicited the greatest interest among kabbalists and scholars of Jewish mysticism, from Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook to Gershom Scholem, was Rosenberg’s Hebrew translation of the Zohar, featuring his deeply learned commentary, Sefer Zohar Torah. This commentary was intended to make the esoteric core text of Kabbalah accessible to the widest possible Jewish readership in anticipation of the messianic age, which Rosenberg predicted, with characteristic brashness, would occur one year after the appearance of its introductory volume titled Sha’arei Zohar Torah (The Gates of the Splendor of Torah).

The literary form of Rosenberg’s Zohar Torah was also bold: He rearranged the classic order of the Zohar to render it as a running commentary to the Tanakh, from Genesis through to Ecclesiastes. In doing so, Rosenberg skipped over those sections of the Zohar that he deemed too esoteric for his intended mass audience, notably the deeply panentheistic Idrot that record the radical teachings of Shimon bar Yochai to his mystical circle during their meetings in Galilee, when some disciples are said to have perished in mystical ecstasy.

Rosenberg was far from the first kabbalist to endeavor spreading such dangerous Jewish mystical secrets to wider readerships. It was Rosenberg’s truly radical justification for revising a centuries-long revered sacred text that really got him into hot water. As Robinson writes:

Yudel Rosenberg’s confidence in his powers as editor was fortified because he did not view his reedition of the Zohar as the first the Zohar had undergone. On the contrary . . . it had evidently been edited in the thirteenth century by Spanish Rabbi Moses de Leon (1240–1305) . . . He was thus far from simply accepting the Zohar as it presents itself. He did not for a moment think that the text of the Zohar in the printed editions was in any way identical to the work that had supposedly left the hands of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who is credited by nearly all traditional Jews as the Zohar’s “author.” . . . In this he agreed with academic students of Kabbalah, who assert that Moses de Leon is the “author” of the Zohar in one or another sense.

Here Rosenberg was flagrantly violating a centuries-long consensus that condemned those who questioned the Zohar’s antiquity and authorship as heretics and banned them (like the Hakham Zvi’s golem) from inclusion in a minyan.

Rosenberg’s revised translation also dared to include corrections to the Aramaic original based on a surprisingly modern text-critical, historical approach. He argued that even if the scrolls inscribed by bar Yochai or his disciples had remained hidden in caves before being discovered more than a millennium later, they would surely have suffered severe deterioration and extensive erasures. Robinson sums up Rosenberg’s daring approach:

For Yudel Rosenberg, Rabbi Moses de Leon had in effect reedited the “original” Zohar. And if Rabbi Moses could do it, for good and sufficient reasons, so could he!

Rosenberg’s intrepid exercise in critical scholarship was however fatally undermined by the web of fabrications he wove regarding his source for Zohar Torah: that same fictional Imperial Library of Metz.

Rosenberg’s fabrications hardly ended there. For example, the front material to the work’s introductory volume features a posthumously released haskamah (endorsement letter) from one of the leading rabbinic scholars of the period, Hayyim Hezekiah Medini (1834–1904), the author of Sdei Hemed, the most thorough encyclopedia of halakhic literature of its time. But the letter—with its highly suspicious stipulation that Rosenberg only publish it after Medini’s death—is almost certainly a forgery. Which is hardly surprising, since Rosenberg’s entire literary oeuvre is marked by similar fabrications. Take, for example, his earlier edition of Sefer Goral ha-‘Assiriyot, a mystical recipe book for summoning oracular responses to every imaginable inquiry. Robinson dryly observes that Rosenberg made the same bogus claim about his sources for the Goral book as he did about the Golem tales.

In presenting so much of his own writings as transcriptions of ancient manuscripts and fabricating his archival sources, Rosenberg was perversely imitating the methods employed by modern Jewish scholars of the Wissenschaft des Judentums school, namely critically copy editing and publishing long-lost—but in their case real—manuscripts. As the list of treasures sent to him by fictional scholars and book dealers with access to treasures from that imagined Imperial Librarykept growing with the publication of each new pseudepigraphal work, Rosenberg’s forgeries took on a life of their own.

Rosenberg’s fake treasure trove of manuscript discoveries pales in comparison with his transcription of revelations from angels and oracles. A striking example is the publication of his 1924 Yiddish sermon, A Briveleh fun di [sic] Zisse Shabbes Malkesa zu Ihre Zin und Tekhter fun[em] [Y]Idishn Folk (A Letter from the Sweet Mother Sabbath-Queen to her Sons and Daughters from the Jewish People) whose every word Rosenberg claimed was disclosed to him by the divine royal chaperone who attends to Jews as they usher in the Sabbath. The Sabbath Queen’s passionate plea to the Jews of Canada to repent of their widespread neglect of the Sabbath laws was combined with a sustained polemic against the many other ills of modernity.

And yet, despite this and many other jeremiads against modernity, Robinson argues that Rosenberg was himself a kind of modernist. In this connection, he adduces Rosenberg’s support of the labor unions demanding a five-day workweek as evidence of his modernizing—even socialist—tendencies. However,this stance was more tactical than ideological, as it would free Jews from having to work on Shabbat.

While exposing the extent of Rosenberg’s forgeries, Robinson also studiously avoids any unmitigated criticism of him as a habitual fabulist. And while never questioning his unwavering lifelong commitment to strict halakhic observance, Robinson portrays Rosenberg throughout the biography as an enlightened Hasid, a “Hasidic maskil,” based mostly on Rosenberg’s deep but anachronistic interest in some aspects of modern technology and the sciences, from physics and mathematics to the sewer systems of modern cities. He was also a kind of halakhic inventor, who built an almost comically elevated baby carriage designed to circumvent the prohibition against its public use on Shabbat and claimed to be able to turn home bathtubs into kosher mikvahs for ritual immersion with a little bathroom renovation.

However, such amateur ventures into the sciences were halakhically driven; as per the medieval formulation, science was viewed not as an autonomous discipline but as a “handmaiden of Torah.” Rosenberg was no more a maskil than Thomas Aquinas was a proponent of the Reformation or Maimonides was a harbinger of the Haskalah. In fact, Rosenberg’s scientific inquiries were generally in service of his most bizarre and controversial halakhic rulings, not as part of any broader agenda for the modernization of Jewish life and education. Most of those rulings are included in Rosenberg’s massive collection of sermons and responsa, recently republishedby his great-grandson in an annotated critical edition Sefer Omer va-Da’at, published by the distinguished Orthodox publishing house Mossad Harav Kook.

Rosenberg’s most controversial and widely debated ruling sanctioned the use of electricity on the biblical festivals, which he justified, in part, by claiming a superior scientific understanding of electricity to that of his rabbinic contemporaries. While his position was never endorsed by a consensus of authorities, those rabbis who did side with Rosenberg included Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein, author of the twentieth century’s most authoritative halakhic codex, Arukh ha-Shulchan, and Ben-Zion Uziel, the first Sephardi chief rabbi of Israel (who befriended Rosenberg during a 1927 visit to Montreal, after which he referred to Rosenberg as “he whom my soul loves”). Rosenberg’s brief for permitting the use of electricity on the Sabbath made him no more of a modernist or maskil than Rabbi Epstein.

It is true that Rosenberg’s eclectic interest in the sciences, homeopathy, and modern technology—already manifest while serving as the Hasidic Tarler Rebbe of Lodz—made him vulnerable to accusations that he was a modernizer by some of Poland’s other shtikl or vinkl (minor or corner) rebbes. But this was mostly a matter of market differentiation, since they all engaged in fierce competition for followers and income. Robinson himself cites a despairing letter that Rosenberg wrote to his son, in which he bitterly decries the accusations by a certain Reb Yekl of Opoczna:

That I am not a rebbe, but only a Maskil, an unbeliever [apikores], and a bit of a doctor, that I have an in-law in Warsaw who is a tailor and a bankrupt, that my son shaves his beard, and that I have explicitly commanded my daughter-in-law to go about with [uncovered] hair.

Rosenberg’s scientific and medical interests were never meant to replace the wisdom of the Torah or the Kabbalah; quite the contrary, they served only to reaffirm the most mysterious and irrational aspects of traditional Jewish belief.

In point of fact, Rosenberg’s fascination with electricity was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it emboldened him to issue his permissive ruling on its use during the Jewish festivals. On the other hand, he hailed the harnessing of electricity as a pre-messianic revelation, reinforcing the kabbalistic doctrine of the Ten Sefirot, which were believed to be something like electrolyzed heavenly orbs through which God’s ineffable attributes were made manifest in the physical universe.

Furthermore, Rosenberg aggressively promoted himself as a miracle-working faith healer whose brisk sale of talismanic amulets constituted a healthy portion of his income. Robinson remarks that Rosenberg’s Sefer Rafa’el ha-Malach was “a curious mixture of the old and the new, of modern medicine, folk remedies, charms, and incantations.” In fact, the book contains not an iota of usable modern medical advice, even by the standards of the day. Robinson’s summation of Rosenberg’s medical methods and pharmaceutical pretensions as “following a centuries-old tradition of collaboration between kabbalists and pharmacists in Poland” suggests as much. He might have added that the often toxic tradition of Polish physicians and pharmacists certifying the sham magical remedies of rebbes had all but ended by the mid-nineteenthcentury, a half-century before Rosenberg’s birth.

In his polemical introduction to the collection of his sermons, Yabia Omer, Rosenberg rails against materialist science for rejecting that nature is God’s handiwork, and denying divine providence, as well as the healing efficacy of prayers, incantations, and consultations with oracles. The same text includes Rosenberg’s angrily satirical depiction of “haskalah-friendly” rabbis:

There is much to complain about those congregations which, when it comes to hiring a rabbi, will only choose a maskil but never a God-fearing haredi. And they derive so much nakhes when this “spiritual leader” preaches so haughtily from the pulpit, and the more jokes he tells to cause laughter, the more praiseworthy he is considered, and the more he kowtows to the community leaders, the more he is admired. Most egregiously, if he manages to weave into his sermons something in the name of one of the Hellenistic philosophers, say Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, or Darwin, Spinoza and Kant, and their like, despite these being heretical utterances . . . the masses in their pews will applaud them, and one will whisper to the other, “You see, our rabbi is a great maskil, not a loser like those haredi rebbes with their beards and payos.”

Rosenberg’s inclusion of Darwin, Spinoza, and Kant in his hit list of heretical “Hellenistic philosophers” is hardly indicative of any serious engagement with Modern Western thought.

Robinson depicts Rosenberg’s jurisprudential approach as one that aimed to find ways to render the observance of halakha possible in the face of modernity’s many challenges, preferring to permit when prohibiting would cause unsustainable financial burdens or unreasonable social hardships for the masses of European Jewish immigrants to the Americas. But this hardly makes Rosenberg radical or unique. The rulings of a distinguished line of early- and mid-twentieth-century halakhic authorities—from the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel, Isser Yehuda Unterman, to the towering American posek, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein—were rooted in a commitment to make the halakha livable in modern times. These lenient adjudicators were wont to cite talmudic principles advising lenience, such as “let Israel be; better they should sin innocently than deliberately” and “we don’t impose stringencies on the community that it cannot withstand.” As has been well documented in scholarship, the inclination to lean toward permissiveness rather than cause hardship has deep roots in both seventeenth-century Polish Jewish jurisprudence and the traditions of Sephardi hakhamim coming out of the Western Maghrebi school of Jewish law.

Nonetheless, Rosenberg’s passion to preserve halakhic observance by constantly devising controversially daring new leniencies and loopholes was particularly striking. Indeed, the apt title of Robinson’s fascinating chapter dealing with Rosenberg’s many madcap inventions and halakhic innovations, “Better to Be in Gehinnom,” is taken from Rosenberg’s heated correspondence with the far younger but already more illustrious authority Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach of Jerusalem. At the end of a skillfully detailed summation of their decade-spanning debate about the permissibility of using electricity on the major Jewish festivals, Robinson quotes from the draft of the fullest version of the letter, which he found in the Rosenberg Family Archives in Savannah, Georgia:

There is a great obligation on the part of the great rabbis of the generation to be on the side of permission as much as possible . . . for just as it is an obligation [mitzvah] to say something that will be obeyed [nishma’], so it is an obligation notto say something that will not be obeyed. For this [prohibiting turning electric lights on and off on Jewish holidays] is a decree that the majority of the community is unable to uphold. . . . If they decree upon me the punishment of Hell [Gehinom] for this [responsum] it would be better for me to be in Hell along with the myriads of Israel who light and extinguish electricity on holidays, rather than be in Paradise [Gan Eden] with the elite [yehidei segulah] who instead of loving righteousness have chosen love of wickedness.

One interesting feature of this dispute is the light it sheds on the widely divergent needs of the respective constituencies rabbis Rosenberg and Auerbach served. Rabbi Auerbach was responding to haredi yeshiva students and scholars of British Mandatory Palestine to whom it would never have occurred to use electricity on, say, Passover. Rosenberg’s Montreal congregants were an altogether different story. It is hard to imagine a halakhic dispute that more vividly illustrates the very different perspectives and obligations of communal rabbis and yeshiva scholars at a time when the former had not yet yielded to the latter, as has happened throughout the Orthodox Jewish world over the past half-century.

The real biographical mystery regarding Rosenberg has to do with his recklessness with reality, which extended beyond his literary forgeries. On this, Robinson is, perhaps rightfully, reticent to engage in armchair analysis. I appreciate and, to some extent, share his methodological reservations, but there seems to me to always have been a self-aggrandizing method to Rosenberg’s

meshugas.

As the sole source for almost all the reference entries about himself, Rosenberg succeeded in establishing many highly dubious and unverifiable autobiographical claims, including that he was the descendant of the famed medieval pietist Rabbi Judah the Hasid, author of Sefer Hasidim, which would in turn make him a direct descendent of the great Rabbi Judah the Prince, redactor of the Mishnah. Alas, Rosenberg does not specify which of his parents was “from the stock of R. Judah the Hasid of Blessed Memory.” This omission freed Rosenberg up to make other fantastic claims about his ancestry. For instance, that his father was a direct descendant of the great eighteenth-century kabbalist and forerunner of Hasidism Jacob Koppel Lipschitz (who, as Gershom Scholem later proved, was a fervent adherent of the Sabbatean messianic heresy). Rosenberg also claimed direct descent, through his mother, from Abraham Joshua Heschel of Apt, the ancestor and namesake of the great twentieth-century Polish American Jewish scholar and mystic. Rosenberg boasted that he was crowned the “Iluy [prodigy] of Skaryzcew” for his brilliance at the tender age of six. By sixteen he was answering halakhic queries for the village’s rabbi, who deferred to his greater wisdom. And so on. That Rosenberg was a learned talmudist, halakhic innovator, impressively prolific author, and passionate defender of Jewish religious observance in Canada at a time of its rapid abandonment are not at issue. What’s most fascinating, and not untroubling, about him was his wildly unfettered imagination that led him all too often to cross the lines between truth and fiction. As it happens, Rosenberg’s own most famous descendant was his maternal grandson, Montreal author Mordecai Richler. Thus did Rabbi Judah the Prince, naturally if weirdly, beget Duddy Kravitz.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Brave New Golems

As monsters go, golems are pretty boring. Mute, crudely fashioned household servants and protectors, in essence they’re not much different from the brooms in the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” story.

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

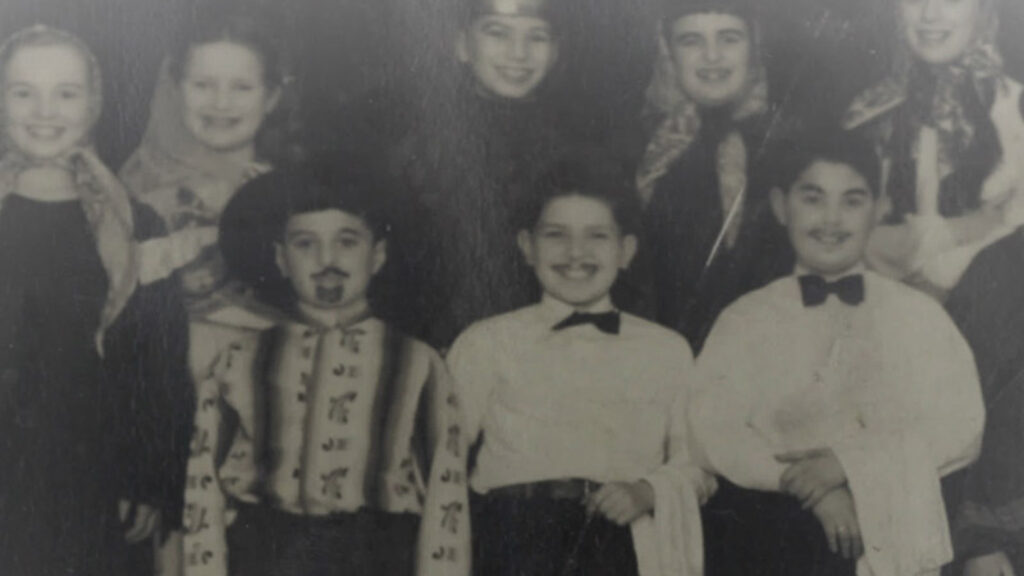

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

Romancing the Haskalah

Should the Haskalah be rebranded as "Jewish Romanticism?” Olga Litvak seeks to bring about a radical change in the definition of Haskalah.

Like Dreamers

How did a large number of religious Zionists come to believe a historical fantasy about the Vilna Gaon’s secret 18th-century Zionist plan?

Lawrence Kaplan

A characteristically insightful review by Nadler, appreciative where deserved, but critical where warranted. The reviews’s last line is a scream. Perhaps Rosenberg should be compared to other noted forgers of his day, the forge of the Palestinian Talmud or the notorious forger, r. Chaim Bloch. With reference to the story of the Maharal in 18th century English novels, just at the beginning of the development of the genre , we have many novels posing as truth with prefaces by editors and publishers.