Like Dreamers

The Russian pogroms of 1881 led Leon Pinsker to issue his pathbreaking 1882 work Auto-Emancipation, which became the manifesto of the Hibbat Zion (Love of Zion) movement. In Western Europe, persistent antisemitism, exemplified by the conviction for treason in 1894 of Alfred Dreyfus in France, inspired Theodor Herzl’s foundational text of “Political Zionism,” The Jewish State (1896), which was followed the next year by the First World Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. Although important work continues to be done on matters of detail and interpretation, the historical crises that gave rise to modern Zionism, the identity of its founding fathers, and its first texts have long been considered settled history among scholars.

Nonetheless, in recent decades Israel has seen the rise of a mythological counterhistory that has been given increasing credence. Large numbers of contemporary religious Zionists believe that the true seeds of the Zionist idea, as well as the real pioneers of the First Aliyah,are to be found a full century before Pinsker and Herzl, among followers of the great rabbinic scholar Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Kramer, the Vilna Gaon (1720–1797). The very first Zionist organization is alleged to have been secretly founded in 1780 with the creation in Shklov, Belarus, of a messianic movement for Jewish national renewal in the Land of Israel, called Hazon Zion(Vision of Zion). Among the many bizarre moments of 2020 was the fact that this historical fantasy was widely discussed and seriously debated in Israeli conferences, symposia, and publications that marked the 300th anniversary of the Gaon’s birth.

The origins of this fiction began in 1951 with a fantastic pseudohistory titled Hazon Zion by Shlomo Zalman Rivlin (1884–1962). In this book, which reads like rabbinic fan fiction, Rivlin audaciously misappropriated virtually every one of the actual initiatives and achievements of Pinsker’s Hibbat Zion movement—propagating the new Zionist idea to Jewish communities small and large across Eastern Europe, organizing Jewish self-defense groups, orchestrating mass aliyot, and even championing the renewal of Hebrew as the spoken language of the modern Jewish nation—and backdated them by a century. The members of Hazon Ziondid this, Rivlin claimed, at the behest of the Vilna Gaon, who was arguably the most reclusive and least political rabbi in history. According to Rivlin, the Gaon’s disciples regarded him as the “Messiah, son of Joseph,” the first, earthly messiah who would inaugurate the messianic era and usher in the “Messiah, son of David.” He would do so, so goes the story, not by miracles but through purely natural means, meaning, more or less, by instructing them in the ways of autoemancipation.

Four years earlier Rivlin had published a bizarre and cryptic text called Kol ha-tor (Voice of the Turtledove), which he claimed was a long-concealed mystical tract by his ancestor, Rabbi Hillel Rivlin of Shklov (1757–1838), whom, he insisted, the Vilna Gaon had sent to Israel as one of his proto-Zionist emissaries. The book elaborates upon the Vilna Gaon’s supposed messianic or pseudo-Zionist interpretations of the dreams of Rabbi Hillel’s father, Benjamin of Shklov, of a rebuilt city of Jerusalem. These dreams, so the story goes, prompted the Gaon to direct his students, including Benjamin and Hillel of Shklov, to emigrate to the Land of Israel and thereby hasten the redemption, which they purportedly did between 1808 and 1810. One inconvenient fact for this story is that there had been no mention of it in the Hebrew literature by and about the Gaon and his students over the previous century and a half.

In 1947, Kol ha-tor drew only minimal interest among a small circle of haredimwho were sympathetic to at least some form of religious Zionism, despite the Old Yishuv’s consistent vilification of Zionism as a heresy. However, over the last five decades, the book has become a key text in religious-Zionist circles, particularly in the study halls of a cluster of ultranationalist yeshivot. Even before the controversies of 2020, this had not gone unnoticed by historians. The first distinguished Israeli historian to take on what has by now been dubbed the “Rivlin Myth” was then dean of the faculty of the humanities at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel Bartal, who argued that Kol ha-tor was a shamelessly pseudepigraphic work whose clear agenda was to argue that the “original” Zionist idea was religious and messianic in nature and had nothing to do with the secular Zionism of Pinsker, Herzl, and their contemporaries.

Kol ha-tor is but the most widely read and influential work from a little library of less mystical but equally mythical works, almost all penned by Shlomo Zalman Rivlin, that spin an elaborately creative web of tales, constituting a fully developed counterhistory not only of Zionism but also of the Jewish settlement of the Land of Israel since the late Ottoman period. Take Yesod ha-mosad (Foundation of the Institute), which records the achievements of the leaders of the Jerusalem-based “Central Council” of the Old Yishuv, founded in 1866 by Rivlin’s father, Rabbi Yosef “Yoshe” Rivlin. The book mixes real history with laughable fantasy. Perhaps the most madcap invention found in Yesod ha-mosad regards the Old Yishuv’s “defense forces,” which Rivlin dubbed “the Gabardia,” consisting of long-bearded men wearing gabardine coats and black hats, sporting long guns and with machetes, going to battle with Arab and Druze enemies of the Jews.

Rivlin’s elaborate, imagined counterhistory of the origins, modern settlement, and earliest “Jewish national” institutions of Eretz Yisrael began to gain traction in religious-Zionist circles shortly after the Six-Day War. In 1968, Rabbi Menachem Kasher published a massive and widely influenztial book called Ha-tekufah ha-gedolah (The Great Era), which explained in excitedly messianic terms Israel’s recent victory and appended the text of Kol ha-tor as if it were an authentic 18th-century document by one of the Vilna Gaon’s disciples. Almost three decades later, another Rivlin family member, Bar-Ilan professor Yosef Rivlin, reissued an expanded version based on an alleged newly discovered “full manuscript” of the text.

Kasher’s publication of Kol ha-tor and the subsequent expanded edition marked a turning point in the Rivlinite myth. It became a key text in certain Zionist yeshivot at precisely the time when many religious Zionists were undergoing a dramatic ideological change of heart. Religious Zionism had originally begun as a pragmatic concession by Rabbi Reines’s Mizrachi Party that allowed religious Jews to join the main Zionist movement and ignore its secularist heresies, and this was still the dominant spirit among rank-and-file religious Zionists through the early decades of the State of Israel. After the Six-Day War, an entirely different, urgently messianic view of the Jewish state’s significance became much more prominent.

The original formulator and most revered theorist of a messianic form of religious Zionism was modern Palestine’s first chief rabbi, Abraham Isaac Kook, and its most effective and fervent proponent in Israeli politics was his son, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook. Needless to say, the first Rabbi Kook had never heard of the Rivlin Myth, since he died in 1935, 12 years before Shlomo Zalman Rivlin began publishing his fantasies. His son was utterly uninterested in them since he, like his father, held to the mystical quasi-Hegelian idea that real, secular pioneers of Zionism were the unknowing fulfillers of God’s final plan for the Jews. Although both of them revered the Vilna Gaon as a rabbinic authority, neither thought that he was any kind of a Zionist a century before Herzl’s First Zionist Congress.

And yet, it was Herzl who said “if you will it, it is not a myth,” which, in this case, was even more prescient than he could have guessed. In May of 1997, precisely a century after the First Zionist Congress, the Knesset devoted a full session to commemorate the 200th yahrzeit of the Vilna Gaon, during which the willed myth of Shlomo Zalman Rivlin’s messianic counterhistory of Zionism took center stage. The speakers, mostly Knesset members representing Israel’s religious-Zionist partyMafdal (the successor to Mizrachi), celebrated the Vilna Gaon’s late-life attempt to hasten the redemption by emigrating from Lithuania to the Land of Israel—of which there is no proof. Many added that, although he was unable to fulfill this “messianic-Zionist” goal, certain of his disciples succeeded in doing so, including Rabbi Hillel Rivlin of Shklov and his father Benjamin, thus beginning to “farm the land and reverse its desolation,” which they considered a necessary and natural precursor to the miraculous arrival of the heavenly Messiah, son of David.

In his address to this Knesset meeting, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu cited a powerful “Zionist” passage from Rivlin’s Kol ha-tor regarding the process of redemption, insisting that it can only begin in a “natural way” (be-derech ha-teva), that is to say, politically. Netanyahu’s speechwriter was clearly, perhaps deliberately, clueless about the deeply dubious authenticity of the work now being all but canonized by Israel’s head of state from its parliament’s podium.

Then-Knesset member and future president Reuven Rivlin, a direct descendent of the very same Benjamin Rivlin of Shklov and a generally admirable public figure, delivered the final address. After summarizing his ancestors’ yichus as Zionist visionaries, almost a century before Herzl’s First Zionist Congress, Rivlin concluded with this dramatic historical judgment:

One hundred years before the emergence of Zionism as a national-political movement, there arose a movement of mystical Zionism at whose helm stood our teacher and rabbi, the Gaon of Vilna.

A dozen years later, Reuven Rivlin introduced a conference at Jerusalem’s Binyanei ha-Umah commemorating the 200th anniversary of the allegedly true First Aliyah (1808–1809), consisting of the migration of some 40 “followers of the Gaon of Vilna” and their families from Lithuania to the Land of Israel at their master’s command, with these words:

Our family [the Rivlins] has the right to be proud to have established itself and planted deep roots in this land over the past two centuries, being among her very first immigrants, one hundred years before the [creation of] the [secular] Zionist movement. Some in our family had the great merit of having spearheaded the aliyah to the Land [of Israel] that had been commanded by the GRA [acronym for Gaon Rabbi Elijah] of Vilna and his students. Herzl and his friends may have sufficient Zionist merits, but the first rights belong to our ancestors, who altered the reality in this land and planted the subsoil of Zionism. Theirs was in fact the First Aliyah.

The problem is that this is nothing more or less than a pure myth, and neither the family pride of Israel’s distinguished president nor the will of political and academic hacks can change that.

What was noticeably ignored—all but censored, really—during both of the 2020 conferences commemorating the Vilna Gaon’s tercentenary at Bar-Ilan University and Ariel University, in which I participated, were two new books which, taken together, thoroughly demolished every detail of the Rivlin family’s alternate history. The first, The Messianic Zionism of the Gaon of Vilna: The Invention of Tradition (2019), is by the distinguished Israeli historian Immanuel Etkes. Etkes, whose work I have drawn on above, presents the most complete narrative history of the Rivlin mythology. I have never read a more thorough demolition of any revisionist history; then again, I can’t think of another historical narrative widely accepted by a significant demographic that rests on so flimsy a basis. Etkes works through its core texts, exposing their every detail as nothing more than pure fiction backed up by pseudepigraphic sources and junk history.

One might wonder why a scholar of Etkes’s stature, the author of definitive biographies of not only the Gaon, but also the Ba’al Shem Tov, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, and Rabbi Israel Salanter, would devote his time to abolishing such spurious fantasies. It is an important act of intellectual hygiene, a service to his country’s intellectual culture, but it also seems to have been fueled by outrage at the transformation of the religious Zionism in which he himself was brought up to which the truths of history no longer seem to matter. One can hear his indignation at Rivlin’s historical inventions in this passage from the very beginning of the book:

The Hovevei Zion were awakened to act on the heels of the waves of pogroms in Russia and the domination of modern Europe by nationalism. By contrast, the students of the Vilna Gaon had supposedly established the Hazon Zion movement under the spell of scriptural and rabbinic esoterica in Benjamin of Shklov’s dreams, for which the Gaon suggested interpretations.

The appearance of Etkes’s meticulous and stunning work was quickly followed by a less conventional work of scholarship by the independent scholar Yosef Avivi, who is widely regarded as the world’s leading authority on the kabbalistic writings of the Vilna Gaon. Avivi gave his work the somewhat playful rhyming title Kol ha-tor: Dor achar dor (Voice of the Turtledove: Generation after Generation). It is, essentially, an incredibly exhaustive annotated casebook of the Rivlin Myth.

As Avivi shows, the myth actually began before Shlomo Zalman Rivlin published Kol ha-tor—but only by a few years. In 1939, Shlomo Zalman’s cousin Yosef Rivlin seems to have invented the alleged messianic role of the Gaon’s students in rebuilding Zion in order to claim the precedence of the Rivlin family in building Jewish settlements outside of Jerusalem’s Old City. Of such historical claims and the many that would follow, Avivi writes there is no evidence from any authentic historical source, and “there is not even so much as a hint, in anything ever written by the Gaon himself, or in anything ever written about him [by his actual disciples].”

Etkes, for his part, has critically assessed the impact of the Rivlins’ pseudohistory, making a passionate case regarding the political dangers of its wide acceptance in the religious-Zionist world, in which he himself was raised but that he now finds all but unrecognizable. He has no patience with a just-so story of the origins of Zionism that completely erases the actual circumstances that led to the origins of modern Jewish nationalism. At times, he cannot resist sarcasm:

So, it turns out that Zionism has connection with neither the Russian pogroms, nor with the rise of modern antisemitism in Eastern, Central, and Western Europe. Nor was Zionism at all influenced by the [emergence of] modern European national movements. What connection do we have with such figures as Pinsker, Lilienblum, Ahad Ha’am, and Herzl, to say nothing of Weizmann and Ben-Gurion? It all really began with the disciples of the Besht (some of whose luminaries began a wave of Hasidic aliyot in the last decades of the 18th century) and then the students of the Gaon of Vilna who went up to the land at the turn of the 19th century, from which there emerged a direct and gradual process of redemption right to the establishment of the State of Israel.

Etkes makes no effort to hide his particular disdain for the work of the popular scholar Arie Morgenstern, who has done the most to propagate and argue for the authenticity of the Rivlin Myth, both in academic circles, where he has mostly failed, and among the religious-Zionist public, where he has largely succeeded. Etkes devotes a long chapter to a withering criticism of Morgenstern’s many books and articles, whose influence in the world of Zionist yeshivot is inversely proportional to its reception among scholars of Jewish history. But it is Morgenstern’s most recent work, both doubling down on his denigration of secular Zionism and alleging new “revelations” regarding the Gaon of Vilna’s own attempt to immigrate to the Land of Israel (via Amsterdam and the Hague, of all places), that truly infuriates Etkes. Here he sees Morgenstern not merely accepting and spreading the inventions of Shlomo Zalman Rivlin but going into the business of fake history himself.

Etkes has more scholarly respect for Professor Raphael Shuchat, of Bar-Ilan University. Shuchat has closely but credulously read the Rivlin documents alongside genuine works of the Gaon and his circle and sketched a picture of the circle’s ideology on that basis, to which Etkes asks an unanswerable question:

If it is indeed the case that the Gaon’s ideas served as the ideational basis for his disciples’ [political] actions, how is it that not one of them ever so much as attempted to arrange these ideas, which appear [in the Gaon’s] works only in the most cryptic, scattered and foggy form, in some systematic way? How is it that not a single student [of the Gaon] ever managed to do what Raphael Shuchat has done in his book?

On several occasions, Morgenstern has offered a brazen answer to such questions that gives the historical game away: “I believe that the Gaon’s position was so well known to all his followers that there was no need to mention it,” he said in an interview. With such “arguments from silence,” one could prove almost anything.

Immanuel Etkes is a cautious historian of ideas, not a psychoanalyst. Still, he cannot help but speculate about two questions that lie at the heart of understanding the life and works of Shlomo Zalman Rivlin: what inspired his fictional counterhistory of Zionism’s origins, and did he actually come to believe it?

Etkes suggests that Rivlin was caught between fidelity to the world in which he was raised, along with love for his father, Yosef Yoshe Rivlin, a towering leader of the Old Yishuv, and his own personal attraction to many aspects of Jewish modernity (he was a cantor and teacher of hazzanut with a deep interest in musicology, among other things). In creating an alternate universe without the sharp oppositions between the staunchly anti-Zionist Old Yishuvof his father and the general secularism of the original, actual Zionists of the First Aliyah, Etkes suggests that Rivlin succeeded in creating the “best possible Yishuv,” in which fidelity to haredi Judaism and Zionism no longer needed to be in conflict. As for the more difficult psychological question, Etkes remains agnostic, although he does suggest that it is possible Rivlin became so steeped in his creative writings that he lost his grip not only on historical reality but on a healthy degree of self-awareness.

As for explaining the remarkably broad appeal in contemporary Israel of the Rivlin Myth, it seems to me that a key enabler of its spread has been the increased blurring, if not quite total disappearance, of the intellectual and cultural lines that once separated the worlds of a significant portion of Israel’s religious Zionists and the haredi sector of Israeli society. For religious Zionists who have, since the steady displacement of classical religious Zionism by its Kookian-messianic incarnation, drifted farther and farther away from the pragmatic Zionism of their parents and grandparents, the Rivlin Myth enables them to claim ownership of the first form of Zionism and fidelity to the “Torah-true” Judaism of the Gaon of Vilna and the yeshiva world spawned by his followers. Better, in fact—they can point to the anti-Zionist rabbis and yeshiva heads in Jerusalem and Bnei Brak, who rule the “Lithuanian haredi” sector in Israel, as having betrayed the Gaon, insofar as they remain opposed to Zionism. This emboldens them to proclaim that the true and only viable version of the Zionist dream is not the secular, pragmatic, and political ideology of its actual historical founders from Pinsker, Herzl, and Nordau, to Ben-Gurion and Weizmann.

Thus, fanciful counterhistory created out of some obscure personal spiritual crisis on the part of Shlomo Zalman Rivlin and a desire to aggrandize the Rivlin family has become the vehicle for something far more serious: a distortion of the country’s founding in the service of an extreme and profoundly unrealistic political ideology.

Recently, I landed on Hillel Rivlin of Shklov’s English Wikipedia page. It describes him as “a close disciple of the Vilna Gaon.” It continues:

Along with some other pupils of the Vilna Gaon, he is credited with having revitalized the Ashkenazi community in what is now Israel (then the Ottoman province of Damascus Eyalet) by immigrating to Jerusalem in 1809.

He was also the author of the esoteric text known as Kol HaTor, that describes the 999 footsteps of the Messiah’s arrival. He is considered one of the patriarchs of the Rivlin family.

The only problem with this brief entry is that, aside from the correct spelling of his name and the accuracy of the year of his death, it contains not a single truth. Hillel’s father, but certainly not he, might only very generously be described as a “close disciple” of the Gaon, nor could he possibly have moved to Jerusalem before 1828, as even Morgenstern has conceded. Finally, as Etkes and Avivi have proved beyond any doubt, “reasonable” or not, Hillel most certainly was not the author of Kol ha-tor,let alone a “revitalizer” of any Jewish community in Ottoman-ruled Palestine. All this is a lesson in how easily mythology can attain the status of reality and in the vital importance of real history as practiced by scholars such as Immanuel Etkes and Yosef Avivi. As my teacher, the late Isadore Twersky, once warned me almost a half-century ago, “the good historian need imagine what is possible far less than know what is impossible.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Gaon of Modernity

Was the Vilna Gaon a great defender of tradition or a radical modernizer?

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

To Spy Out the Land

A palm tree over one grave and a fence around another—two new books explore the history and legacy of the Nili spy ring.

Zionism’s Forgotten Father

Nathan Birnbaum, one of Zionism's early leaders, looked like Herzl and wrote like Herzl (albeit not as successfully). But his unusual trajectory has reduced the space that might have been assigned to him in the history of Zionism.

David Eisenberg

My mother is a first cousin to Ruvy Rivlin. I would like to know on what basis the comment about Hillel Rivlin was made: that he couldn't have come to Palestine/Jerusalem before 1828. A family genealogy says he came in 1809 and died in Jerusalem in 1838. The YIVO Encyclopedia entry for Shklov says Hillel Rivlin's father, Binyamin Rivlin founded a Yeshiva in Shklov and was a disciple and close associate of the Gaon of Vilna. That entry also cites the founding of a club (not by Hillel Rivlin) that wanted to immigrate to Palestine and that hundreds did so in 1808-1809. Could Dr. Nadler please comment.

Thank you from Skokie, Illinois

David Eisenberg

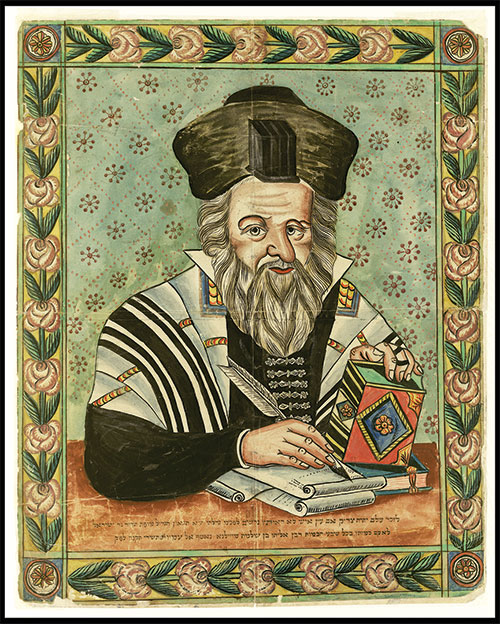

The article has at least two inaccuracies: Yosef "Yoshe" Rivlin was born in 1836, accoarding to Wikipedia, so the picture of him in the artiicle with the date "1838" cannot possibly be correct. Also according to a Rivlin genealogy, Binyamin Rivlin, the father of Hillel Rivlin, did not go to Palestine. He died in 1812 at the age of 84. And if Hillel Rivlin went to Palestine in 1828, he would have been 71 years old.