The Jewess Mystique

In Blanche Bendahan’s 1930 award-winning novel, Mazaltob, the eponymous protagonist Mazaltob Macías is often referred to by members of the Jewish community in Tetouan, Morocco, as “the beautiful little girl” or “the beautiful Jewish girl.” Her Uncle Salomon gazes at her and thinks, “What a sweet child! Naïve and beautiful in equal measure!” (Her name might be translated as “Good Luck Messiah.”)

The belle juive (beautiful Jewess) is a stock figure in European literature with a long afterlife, often portrayed as a woman who has to be freed from her tradition and family, embodied in a despicable father or husband. Think of Jessica in The Merchant of Venice, who defies Shylock and elopes with penniless (but Christian) Lorenzo; Rebecca, who is tragically exiled in Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe; the doomed heroine of Halévy’s opera La Juive; but also Deborah Feldman’s semiautobiographical character Esty in the Netflix series Unorthodox, who escapes Satmar Williamsburg for Berlin, leaving her lecherous husband and oppressive tradition behind. Efraim Sicher and Noa Sophie Kohler trace the trope in their book, The Jew’s Daughter, in which they argue:

The pairing of the wicked Jewish father (who represents the Jews’ collective refusal to accept the Christian messiah) with his beautiful Jewish daughter (who rejects the Law of the father and can be converted to Christianity) repeatedly allegorizes the tension between Old and New Testaments, spirit and flesh, law and dispensation, obedience and rebellion, and, in a problematic way, morality and erotic desire.

The romantic desire of the belle juive is an indictment of the Jewish law under which the woman is trapped, yearning for love, fulfillment, and conversion (though when that is impossible, a tragic death looms). As coeditor and cotranslator Yaëlle Azagury recognizes in her afterword, Mazaltob conforms to this literary stereotype, though she insists that Bendahan rejected “the irksome Belle Juive portraits found in the ambiguously antisemitic descriptions of her contemporaries,” a point on which there is room for some doubt.

Perhaps with a non-Jewish and French public in mind, Mazaltob closely retells the charming customs of Jewish Tetouan. The protagonist’s life is punctuated by the traditions of her Sephardi North African community, known as the Judería, and their language Haketía(a form of Western Ladino) infuses the French prose of the novel. Mazaltob wears a long black dress called a touféra; we hear about the food she and her family eat, including adafina (a hamin or cholent, spiced with harissa) and albóndigas (a meatball soup). Before Shabbat, she chants a hymn:

This new trousseau

Before thou I shall display.

Mother and sister-in-law

Thou will have nothing to say.

This our bride

Kept a vigil doing embroidery by candlelight.

Life in the community of Tetouan is heavily determined by conventional gender roles and ancient Jewish tradition. Mazaltob’s mother and simpleminded sister are preoccupied only with looks and childbearing, while the men in the family are chiefly concerned with serving God and telling Mazaltob what to do. (“Whether you like it or not,” says her Uncle Solomon, “Mazaltob, the finest flower of Israel, will fulfill the destiny promised in her name one day.”)

As she prepares for her wedding at the tender age of thirteen, Mazaltob’s house is filled with noise and bustle. The women of the family crush almonds and prepare pastries for the party, humming old Castilian melodies. Her groom, the wealthy José Jalfon, is a millionaire who made his money in Argentina and often dreams about the tempting women of Buenos Aires (at the time, Argentina’s Zwi Migdal, the infamous prostitution ring of “blancas” created by Polish Jews and named after its founder, was on the rise). All of a sudden, the beautiful girl with the auspicious name finds herself trapped, not only by a man but by the patriarchal community of Tetouan, their invasive gossip, and strict outlook on life.

To escape, Mazaltob reads French novels and befriends the members of a small, Ashkenazi family, presided over by Dr. Bralakoff (“Born at the end of the world—in Russia”). She also takes singing lessons with the wife of the French consul, and while she sings, she seems to flee “far from the bleak bondages of her life”:

Mazaltob sings and the sky seems higher. Vast expanses of green materialize in place of the stifling Judería.

Through the foliage, young girls dressed in white suddenly appear dancing and holding hands. Mazaltob sings. She then joins the next round of dancers.

How light she feels . . .! What a sweet exhilaration . . .! The morning bursts with chattering birds and sparkles everywhere with myriad droplets of dew.

Mazaltob sings. A blonde creature, beautiful as an angel, sits at her feet. A blonde creature, with crystal blue eyes. . . .

For her books have already opened up new horizons for Mazaltob beyond the narrow Judería. And yet, like her sisters, she remains bound by the strict law of Moses.

Bendahan’s mimicry of this community, at times, verges on parody. Sephardi culture is portrayed as God-fearing, provincial, and patriarchal, albeit beautiful; European society, like the one Mazaltob imagines as she sings in French, is refined, liberating, and a source of yearning for our doomed belle juive.

Blanche Bendahan (née Blanche Jeanne Benoliel) was born in 1893 in Oran, Algeria, a few hundred miles away from Tetouan. Although her biography is obscure, Azagury and her coeditor and cotranslator, Frances Malino, relay the known facts about her life dexterously, if perhaps credulously. Bendahan, they write, was a citizen of France and the daughter of a Moroccan Jewish man and a Catholic woman who died during childbirth at age nineteen. Her father later remarried another Catholic woman, Marie Hortense Ginoux, to whom the novel is dedicated.

Unlike Mazaltob, Bendahan seems to have spent her childhood in France, between Nice, Marseille, Paris, and Grenoble. After marrying a colonial goods merchant, she moved back to her hometown in Algeria. There, she had a prolific literary career and was lauded for her work as a poet, novelist, and journalist. In Oran, Bendahan founded her city’s chapter of La ligue française pour le droit des femmes, the French League for Women’s Rights, and organized a literary conference on the subject. Her life, indeed, seems to have been closer to that of her Ashkenazi characters than to the Tetouani Jews she lovingly describes but continuously criticizes. She neither lived in Tetouan nor had a full experience of the limitations of Oran’s traditional Jewish community.

Perhaps because it united two political trends of the time (feminism and a collective suspicion, if not hatred, of the Jews) Mazaltob collected prizes from the French Academy, the French Academy of Humor, and the City of Nice, among others, when it was published.

When her husband abandons Mazaltob, childless yet married, the stage is set for tragedy. We see her slowly becoming a woman while living in her parents’ house. She experiences the pains and nostalgia of adolescence and falls in love with Jean, the half-Christian and half-Ashkenazi nephew of Dr. Bralakoff.

The clash of desire and convention ensues. As a married woman, the impossibility of Mazaltob’s love for Jean is a fatal, romantic wound. Meanwhile, her mother dies, and she falls prey to an evil stepmother. Her sister—who, we are told continually, is her exact opposite, being ugly, dull, and eager to realize her biological destiny—gets married as well, struggles with fertility, and ends up having a girl, which is seen as a misfortune. Mazaltob is once again left behind as a singular creature, of extraordinary beauty and talents, of pristine virginity and virtuosity, but unable to fulfill her potential. The second half of the novel traces this arc from early womanhood to tragedy. One imagines Mazaltob singing, now in English, like Catherine in Wuthering Heights, “I wish I were a girl again, half savage and hardy, and free.”

In the end, a narrative that was ambivalent and sometimes joyous becomes an unambiguous tragedy. Mazaltob thinks about eloping with Jean, weighing the consequences for her community: “How could she face the wrath of the Rabbi who once married her? How could she face the hostility of the Judería, so strict on matters pertaining to the virtue of women?” Mazaltob yearns to leave the Law of Israel behind and instead live freely with Jean under French law instead. As she meets Jean and heads toward happiness, fleeing the Jewish Quarter, she’s overtaken by guilt and exclaims: “I cannot . . . I cannot . . . Leave without me.”

Pained with one of those mysterious, psychosomatic diseases of nineteenth-century fiction, the beautiful Mazaltob finally dies, consumed by her frustrated yearning. She hears the Shema in French as she is dying and longs to be buried next to Jean. In the end, Mazaltob’s tragedy is not exactly that of the belle juive whose father refuses to accept the Christian messiah but of a young woman struggling between the old world and the new.

Azagury and Malino have translated Bendahan’s text beautifully, and their footnotes, introductions, and explanations supply necessary context. However, they make a confusing and arguably unnecessary case for Bendahan’s importance as a novelist. The beauty of the prose and the fascination of the Jewish Tetouani community (notwithstanding Bendahan’s own ambivalence) should have been enough, but they seem to want the novel to fit into categories that aren’t really suitable. They argue that Mazaltob has been neglected because of the lack of interest in Jewish communities from Algeria and Morocco, on the one hand, and the marginalization of Sephardi literature and female authors by Jewish readers and critics, on the other. And yet Bendahan seems to have been addressing a largely secular, feminist, and non-Jewish public—and was richly rewarded by the French literary establishment for doing so. This emphasis on alleged victimhood and marginalization does her novel a disservice. Her heroine is not an expression of our contemporary ideals but rather a twentieth-century Jewish woman caught between two possible lives, between her desires for freedom and her appreciation for tradition.

Azagury and Malino also insist on calling the novel part of the canon of “Sephardi modernist literature,” a field they do not describe further but that perhaps suggests the experiments of later Sephardi writers such as Elias Canetti and Ammiel Alcalay. At the same time, they insist on pointing out the novel’s “ethnographic” value, “realism,” and scrupulous attention to geography. They describe this scholarly accuracy as “gleaned from [Bendahan’s] childhood visits and those she made as an adult” to Algeria but also as informed by “scholarly or auto-ethnographic accounts.” Did Bendahan write a modernist novel attempting to “make it new” or an ethnographic portrait of the beauty and oppression of Tetouani Sephardi life? Or did she, perhaps, write a brilliant and ambivalent piece of feminist fiction about a Jewish woman repurposing the old (antisemitic and antifeminist) trope of the beautiful Jewess?

Suggested Reading

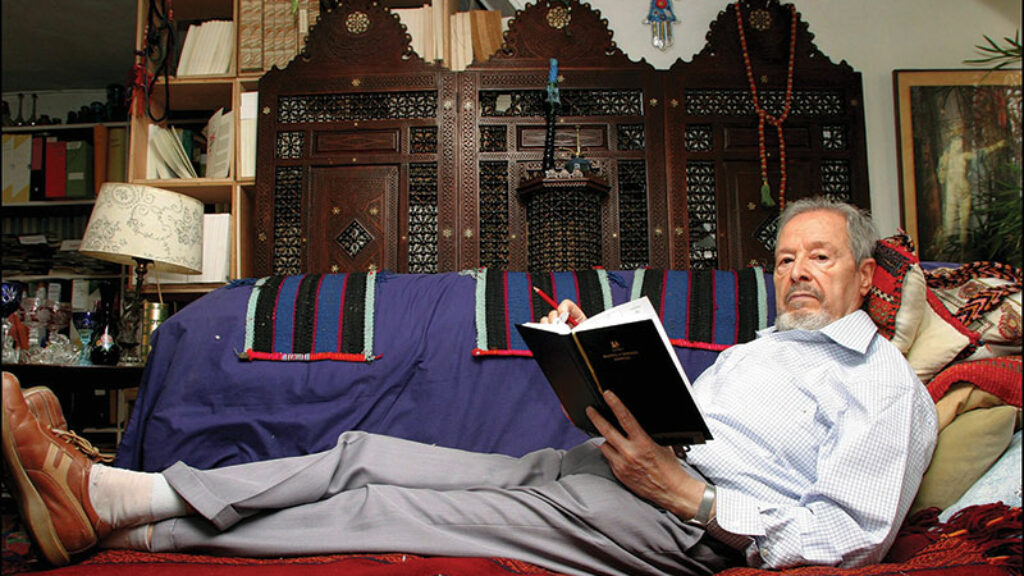

Telling the Whole Truth: Albert Memmi

Albert Memmi began his career as a writer of fiction, but, with the appearance of The Colonizer and the Colonized in 1957, the novelist who wrote like a sociologist became a sociologist who wrote like a novelist.

“I am an Object Loved by God”: Rereading Clarice Lispector

The great Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector rarely acknowledged her own Jewishness but when the Jornal do Brasil fired her a few days after the Yom Kippur War broke out, something changed.

Chaim Grade: Portrait of the Artist as a Bareheaded Rosh Yeshiva

Grade attempted to perform the impossible: to undo in literature what had occurred in history and revive the dead of Jewish Vilna.

Memories of Morocco

In the 1940s Moroccan Jews were still sacrificing a bull on the Sultan’s doorstep. There was a deep cultural symbiosis of Jews and Muslims in North Africa.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In