Who Accuses?

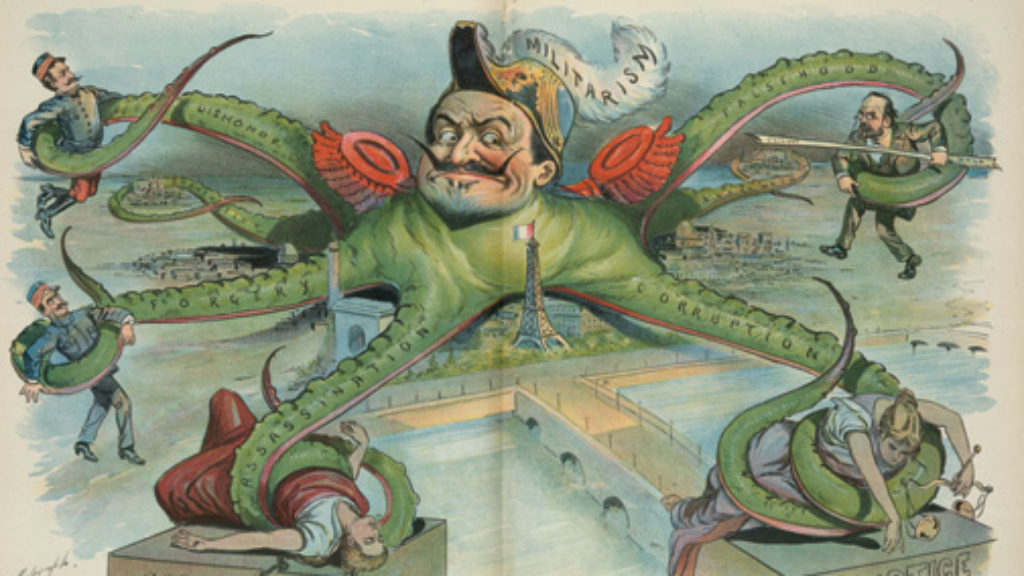

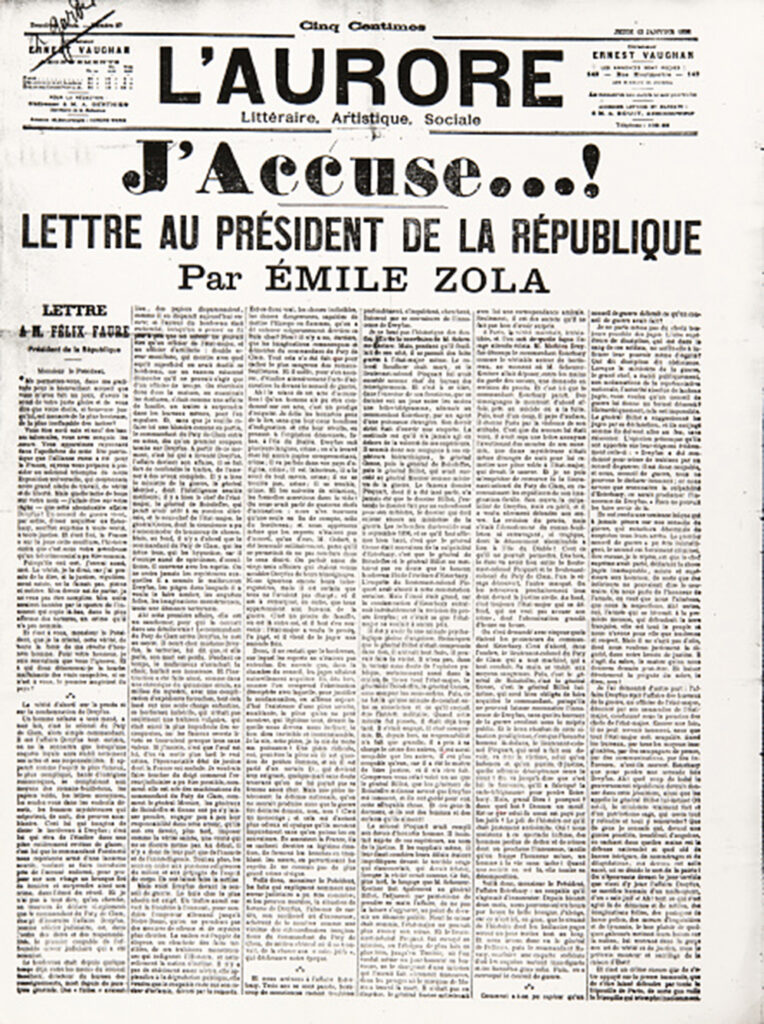

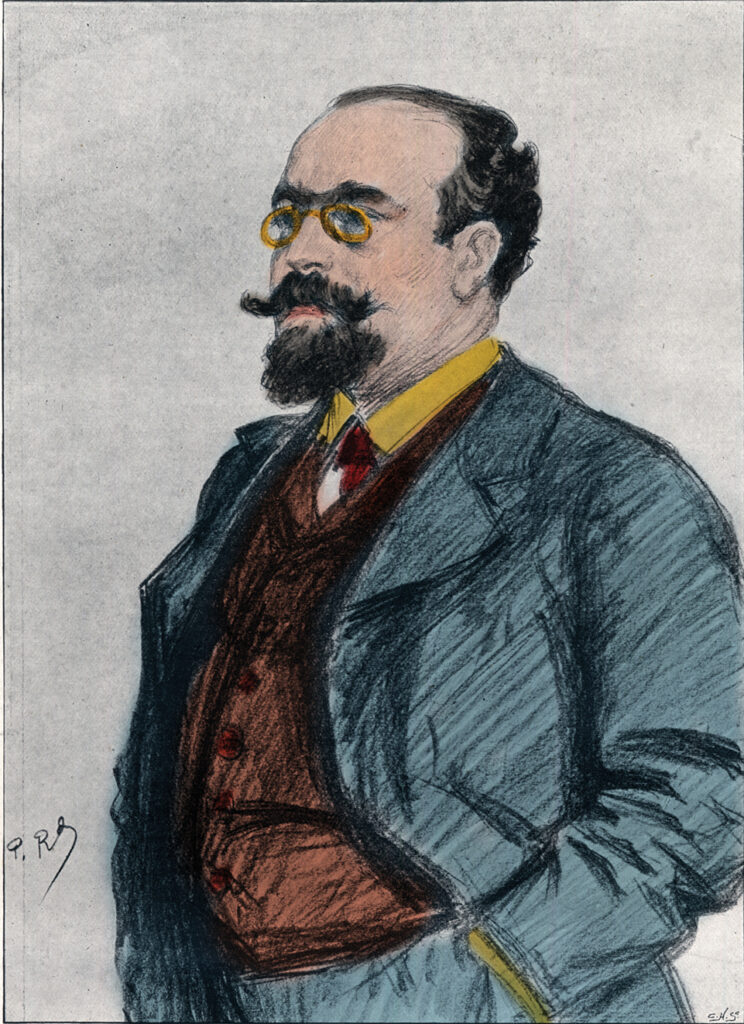

Émile Zola came late to the Dreyfus Affair. When his famous “J’accuse” appeared on the front page of the Paris newspaper L’Aurore in 1898, Alfred Dreyfus, the Jewish army officer wrongly convicted of treason, had already been imprisoned on Devil’s Island for three years. Nevertheless, with a single headline and in a single day, Zola managed to draw back the curtain on the years long spy scandal, uncovering motive and plot and naming names.

Though written as an open letter addressed directly to the French president, “J’accuse” reads more like the libretto of a tragic opera. It concludes with a series of accusations against the men who whipped an entire nation into antisemitic fury and conspired to sentence an innocent Jew to unspeakable suffering, all to protect themselves and the “honor” of the French Army:

What a nest of vile intrigues, gossip, and destruction that sacred sanctuary that decides the nation’s fate has become! We are horrified by the terrible light the Dreyfus affair has cast upon it all, this human sacrifice of an unfortunate man, a “dirty Jew.” Ah, what a cesspool of folly and foolishness, what preposterous fantasies, what corrupt police tactics, what inquisitorial, tyrannical practices! . . .

I accuse Lt. Col. du Paty de Clam of being the diabolical creator of this miscarriage of justice. . . . I accuse General Mercier of complicity, at least by mental weakness, in one of the greatest inequities of the century. I accuse General Billot of having held in his hands absolute proof of Dreyfus’s innocence and concealing it, thereby making himself guilty of crimes against mankind and justice.

The list of accusations went on.

Zola’s “J’accuse” is rightly considered to be one of the most influential newspaper articles in modern history. It generated a popular uprising that challenged the French government, galvanized French antisemites, and established a new role for prominent writers and intellectuals in European political life. Indeed, it is arguably this newspaper manifesto rather than his more than two dozen novels depicting French social life for which Zola is now remembered.

But it was not the first time that clear evidence of Dreyfus’s innocence had been published and not even the first time the words “J’accuse” had appeared in connection with the case. The arguments and phrasing that made “J’accuse” a journalistic masterpiece had been written years earlier by someone else—a Jewish author named Bernard Lazare.

Lazare was a literary and social critic who wrote one of the first books on the history of antisemitism and worked closely with Captain Dreyfus’s family after his conviction in 1894. Lazare traveled abroad to consult with several handwriting experts to prove that the key piece of evidence, the bordereau (a handwritten memo offering to sell French military secrets to Germany), had not been written by Dreyfus. He met with leading intellectuals, parliamentarians, and Jewish and non-Jewish leaders across Paris to share his findings, and wrote a series of pamphlets between 1895 and 1898 demonstrating that Dreyfus had been framed and wrongly convicted.

“Why was Captain Dreyfus specifically chosen?” Lazare asked in the 1895 draft of his first pamphlet. “Because Captain Dreyfus was Jewish. . . . The calculation was accurate, the press leapt on the Jew and the call to justice was stifled.” The draft went on to place blame for the scandal on a cabal of antisemitic military officers, whom Lazare directly accuses in no uncertain terms. It is here, the archives reveal, that the famous “J’accuse” language originates:

As for me, I accuse General Mercier of failing in his duties, I accuse him of having misled public opinion, I accuse him of having carried out a campaign of inexplicable libel against Captain Dreyfus in the press, I accuse him of having lied. I accuse General Mercier’s colleagues of having failed to prevent this injustice, I accuse them of having helped the Minister of War to hinder the defense, I accuse them of having done nothing to save a man they knew was innocent.

Thus, Lazare anticipated Zola’s “J’accuse” refrain by nearly three years. The content of the accusations also closely approximated the real circumstances behind Dreyfus’s wrongful conviction, which it would take the French government another eleven years to acknowledge. Lazare wrote this draft in mid to late 1895, but the Dreyfus family and their lawyer thought it was too inflammatory to publish. They asked Lazare to edit out the “J’accuse” wording before allowing it to be published a full year later under a title that implied the French military’s mistake had been an honest one: A Judicial Error: The Truth about the Dreyfus Affair.

Still, the pamphlet successfully returned the Dreyfus Affair to the front pages of national newspapers and offered the first complete account of the events from a nongovernmental source. Even more importantly, it challenged the narrative and evidence given by the government, questioning every aspect of the case, including the procedures used to convict Dreyfus in the first place. It also contained one small echo of Lazare’s original draft, a single mention of Dreyfus’s Jewishness: “Let it not be said that, having a Jew before us, justice was forgotten.” The pamphlet was, in the words of historian Ruth Harris, “the first properly argued defense of Alfred Dreyfus in print.” And yet, it was quickly dismissed in many quarters of French society for the simple reason that it had been written by a Jew.

Despite Lazare’s best efforts to make sure the pamphlet was well received (he hand-delivered copies to newspaper editors and parliamentarians across Paris), it was widely condemned. The press almost universally focused on Lazare’s one mention of Dreyfus’s Jewishness—and the fact that the pamphlet’s author was Jewish. They suggested it was Lazare himself who was trying to foment an antisemitic scandal. “Mr. Bernard Lazare brings antisemitism into play in an affair which has nothing to do with it. In all the great treasons, since Judas Iscariot, there has always been a Jew, and sometimes several,” remarked the right-wing newspaper L’Intransigeant. An editorial in another paper read, “Mr. Bernard Lazare greatly flatters himself if he believes that between his opinion that flatters a coreligionist, and the opinion of the many officers who have had to endure the shame of condemning a colleague, public opinion will hesitate.”

Lazare became a public pariah. Undeterred, he continued agitating for Dreyfus’s case, publishing a second, revised edition of A Judicial Error in 1897 with even more evidence of Dreyfus’s innocence, and then a third pamphlet in January 1898 that laid out his most forceful argument yet. Titled How an Innocent Man Is Condemned, this pamphlet recovered some of the lines Lazare had discarded from his original 1895 draft, the lines that repeated with rhythmic emphasis his accusations against the military: “I accuse Commander Esterhazy of having fabricated [evidence], I accuse Colonel Paty du Clam of having been his accomplice and of having crafted this false case.” Zola’s “J’accuse” appeared the next day.

How Zola came to appropriate the language of “J’accuse” from Lazare remains one of the unanswered questions surrounding the chaotic events of early January 1898. Archival documents, including a detailed account offered by the trusted “Dreyfusard” publisher P. V. Stock, suggest that several people, including Lazare, helped facilitate both Zola’s writing and L’Aurore’s printing of the piece. We know that it was L’Aurore editor Georges Clemenceau who made the crucial decision to print the article under the huge headline: “J’accuse . . . !”

Lazare never sought any acknowledgment for his contribution, while Zola was happy to take full credit for his rhetorical tour de force. “Zola believed himself to be the man of the moment and elected himself to the role,” Harris writes. “He cast himself as . . . the lone individual fighting against the forces of corruption and decay.” Few noticed or cared that Zola had been utterly disinterested in the affair just months earlier, becoming attracted to the drama of it only in late 1897, once Dreyfus’s innocence and the army’s guilt had been all but proven.

Historians have been reluctant to question the near-mythical status of Zola’s triumph. In her 1978 biography of Bernard Lazare, British scholar Nelly Wilson notes that Lazare’s influence over Zola was “more considerable than has been recognized,” even describing Lazare’s third pamphlet as “an earlier version” of Zola’s article. But she rejects the claim by Zola’s friend Urbain Gohier that “‘J’accuse’ was dictated to Zola by Bernard Lazare.” In addition to Gohier being an unreliable source (he was subsequently the French publisher of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion), the notion of Lazare dictating to the great novelist is absurd, Wilson argues, simply because “Zola was not a man to whom one dictated.”

Was Zola, however, a man who borrowed? French historian Alain Pagès affirms that Zola drew heavily from Lazare’s pamphlets:

It is from this work, both modest and precise, that Zola drew support for his convictions. He read and re-read Bernard Lazare, he shared his outrage on the role played by du Paty de Clam in particular.

But Pagès also refuses to say that Zola copied Lazare, noting that “the expression ‘J’accuse’ is repeated only twice in this thin brochure, which hardly any newspaper mentions.” Of course, that was the pamphlet as published, not the 1895 draft quoted above in which “J’accuse” is repeated seven times in the course of a paragraph. Historian Philippe Oriol goes a bit further. He suggests that Lazare may have given Zola a number of background papers, among them the pages of his first pamphlet draft, which would have been “a happy find” for Zola as he prepared the fateful text.

Under Zola’s byline, “J’accuse” took on fresh power and meaning. It forced the French to confront the fact that their modern republic was riddled with an ancient hatred. The same could never have been achieved by Lazare, and by 1898 he must have known that. As he later recalled, “I remained silent until the day after the [second] condemnation of Dreyfus, when I published, before Zola’s ‘J’accuse,’ my own brochure: How an Innocent Man Is Condemned.” Lazare certainly knew that a famous Gentile novelist would be a more effective spokesman for Dreyfus in fin de siècle France than a relatively obscure Jewish intellectual. But with his preemptive third pamphlet, it would seem that he wanted history to record those words under his own name, as well.

It was not easy, even for Zola. After he published “J’accuse,” he was tried and convicted of libeling the French state and fled to England—in the company of Bernard Lazare. The two remained there together as the affair raged on. Though Dreyfus received a pardon in 1899, he would not be completely exonerated until 1906. (Dreyfus, who, it has been said, understood the Dreyfus Affair the least, returned to the army and fought for France as a reserve officer in World War I.)

The Dreyfus Affair is one of the most studied events in the history of modern antisemitism, and yet at least one of its lessons still escapes us. We read Zola saying “I accuse . . .” and focus our attention on the accusations. But the success of the article crucially depended on the “I” that was doing the accusing. It was Zola’s literary celebrity, his reputation as a man of the people, and, perhaps most importantly, his non-Jewishness that made the accusations of antisemitism stick. Then as now, whose voice is heard and believed may reveal more about a society than the words that follow.

Suggested Reading

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

Melting Pot

Joan Nathan's search for Jewish cooking in France yields some surprising results.

Emancipation Terminable and Interminable

The modern "emancipation of the Jews" can be said to have begun a lot earlier than historians used to think, but has it really not come to its end?

The Jewess Mystique

An early feminist novel about a North African Jewish damsel in (Jewish) distress.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In