Emancipation Terminable and Interminable

On the eve of the French Revolution, the Jews of Avignon—then under the control of the Vatican—lived in an overcrowded and miserable ghetto that they were only allowed to leave during daytime; the gates were locked at night by a guard whose salary the Jewish community was required to pay. Similar conditions prevailed in Germany, Italy, and eastern France, although male Avignonnais Jews still suffered the then-unusual indignity of having to wear yellow hats. Strasbourg was one of many cities where Jews were not allowed to live at all, although Jewish merchants could come there to do business if they paid a special fee (and extra if they brought animals with them). In Austria, Jews were forbidden from leaving their houses before noon on Sundays and from shaving their beards, and, while Christian wholesale merchants and university graduates could carry daggers, Jewish ones could not. When Emperor Joseph II—one of Europe’s most enlightened rulers—issued his Edict of Toleration in 1782, he revoked those prohibitions but still forbade Viennese Jews from having a synagogue or printing press and required Jews to get a special permit before they could marry.

Since the 19th century, students of Jewish history have referred to the process by which these rules and regulations were repealed and eliminated as “emancipation”—a term somewhat confusing to Americans, who associate it with the freeing of the slaves. When and where this process started, how and why it took place, and what it wrought have long been some of the major questions underlying the study of modern Jewish history.

Twentieth-century historians, led by such towering figures as Jacob Katz and Arthur Hertzberg, who focused overwhelmingly on France and Germany, ascribed much significance to the European Enlightenment and its Jewish stepchild, the Haskalah, and tended to date emancipation between 1781 and 1870. More recent scholars have tried to overthrow, or at least refine, this version of modern Jewish history, arguing that the process of emancipation really began much earlier and had little to do initially with enlightened ideals of political equality. These scholars locate the beginning of Jewish emancipation in the economic changes of the 16th century that led some port cities—many of which had expelled their Jews during the previous 250 years—to grant rights to Jewish communities in the hope of fostering trade.

Yale historian David Sorkin’s Jewish Emancipation: A History Across Five Centuries is the first-ever comprehensive study of the subject. Beginning with these 16th-century port cities and continuing to the 20th century, encompassing all of Europe as well as North Africa, the Middle East, and the United States, Sorkin has effectively codified the newer approach.

But Sorkin’s goal is not merely to write an encyclopedia of emancipation. In the acknowledgments, which appear on the final pages, he writes that “this book’s basic conceptualization of emancipation, not to mention its conclusions, is highly controversial.” He lays out his conclusion in the form of “Ten Theses on Emancipation,” but the most controversial points can be boiled down to two. The first: Emancipation was ambiguous and interminable. It was neither a one-time, chronologically discrete event nor a linear one. It was recurring. Jews gained and lost and regained and re-lost rights. Since this process never comes to an end, he writes, “Jews everywhere continue to live in the age of emancipation.”

The second point involves Sorkin’s aim “to redirect the focus of modern Jewish history” from “the two colossal events of the mid-twentieth century, the Holocaust and the State of Israel’s foundation,” to the “neglected yet foundational event of the past four and a half centuries.” Recognizing that “the murder of six million Jews and the establishment of a Jewish state were events of monumental importance,” he nevertheless insists:

Those two events mark neither the consummation nor the culmination of modern Jewish history. In fact, both are part and parcel of the long history of Jewish emancipation. They were reactions to, indeed, developments from, emancipation. In philosophical parlance, they were epiphenomena. Emancipation was, and remains, the principal event.

The “turning point” in the unfolding of this centuries-long “principal event,” according to Sorkin, was the decision of the Italian city of Ancona, at the time controlled by the papacy, to allow Jews, Muslims, and Greek Orthodox Christians to do business there in 1514. Thanks to Jewish lobbying, a formal charter was issued 30 years later, giving them residency rights as well:

The charter granted Levantine Jews freedom of trade and movement; exemption from local jurisdiction and taxes; amnesty for crimes committed elsewhere (treating them “as if born into the world today”); and the right to build a synagogue. The charter set no limits on the period of residence, creating the basis for the permanent community that the Jewish . . . merchants sought.

Venice, Livorno, and other Italian cities, as well as Bordeaux and Hamburg, followed in granting similar charters. Around the same time, England and the Netherlands—where medieval social structures were weakening and the seeds of religious toleration were starting to sprout—began allowing Jews to settle in their respective capitals without the benefit of a charter.

None of these regimes, as Sorkin acknowledges, went so far as to erase all distinctions between Jews and Gentiles. But he argues that these steps constitute something different from the privileges and charters of the medieval period, which treated Jews as a distinct “corporation”—like townsfolk, nobles, clergymen, or guilds—that received its legal status collectively rather than as individual citizens:

Whereas privileges in corporate society are conceptually distinct from rights in civil society, historically they were not. Citizenship in civil society emerged from citizenship in corporate society; parity of privileges in corporate society could lead to equality in civil society.

As Sorkin emphasizes throughout the book, emancipation was a fuzzy matter. But, he argues, the changes in Jews’ status during this period were extensive enough to constitute a break with the past—if not an entirely clean one; there were no clean breaks. Take, for instance, the case of Livorno, then in the Duchy of Tuscany, where the 1593 charter went beyond the one in Venice to introduce “parity of privileges in multiple realms while also recognizing Jews as Tuscan ‘subjects.’” The duke granted Jews “all of the privileges, rights and favors which Our merchants, Florentine and Pisan citizens and Christians, enjoy.” It allowed them to engage in all trades, including retail, exempted them from any special clothing or sign, and permitted them to purchase real estate.

In other words, it went much further than perhaps any previous Jewish charter while at the same time preserving Jews’ corporate status. Moreover, it included privileges more extensive than those Livorno granted to Armenian, Genovese, and Dutch merchants or to any other similar groups. Theoretically, it was an extension of the corporate, pre-emancipatory model, but, substantively, it almost put an end to separate Jewish status. More radical still was what occurred in Bordeaux, Amsterdam, and London, where Jews possessed even greater rights and, in the 17th and 18th centuries, would “make virtually seamless transitions from corporate or civic parity to equal citizenship.”

To Jacob Katz, the doyen and most vigorous defender of the old-school understanding of Jewish emancipation, what occurred in Italy, France, and the Netherlands were only half measures, not principled systematic reform. Part of Sorkin’s rebuttal comes from his insistence that emancipation almost never happened overnight and always consisted of half measures; it was moreover a “one step forward, two steps back” process, as much so in the 18th and 19th centuries as in the 16th and 17th.

The German lands display most fully the complexity of the situation in the 19th century. Until then, Germany’s fractured, byzantine political structure meant that the status of the Jews varied among hundreds of differing jurisdictions, ranging from outright exclusion to burdensome regulations. To live in Berlin, the center of the Haskalah, Jews needed special permits, granted on a case-by-case basis. The philosopher Salomon Maimon, whom Kant praised for understanding his work better than any other, was at first rejected at the city gates. Of course, Jews could also use these rules to their advantage; when Maimon’s overindulgence at beer halls and brothels became an embarrassment, his erstwhile patron Moses Mendelssohn had him thrown out.

All this changed when Napoleon’s armies conquered much of Germany, imposing emancipation wherever they went. After his defeat in 1815, the various German states reinstated most but not all discriminatory regulations and then began re-emancipating their Jews incrementally—thus, the poet Heinrich Heine’s wry lament that he might not have converted to Christianity had Bonaparte’s schoolmaster remembered to teach him that Russian winters are very severe.

Given just how much has been published to date on German Jewry, it’s both surprising and illustrative that this is where Sorkin appears to have done the most original research, simply because the details are so tangled. Each of the dozens of small independent statelets that comprised Germany vacillated over what to do with its Jews, and some were inconsistent from one portion of their territory to another.

A particularly telling example is Prussia’s 1833 edict regarding the Jews of the province of Posen (now northwestern Poland), which expelled some Jews, “tolerated” others, and “naturalized” others. Naturalized Jews, according to the statutory language, were granted “equality with Christians” but still couldn’t hold public office. As for the tolerated Jews, Sorkin notes ironically that, “Aside from the lengthy list of onerous restrictions,” they were “equal to Christians,” per article 27 of the edict. And should a Jew live in Silesia, Berlin, Cologne, Königsberg, or any other Prussian territory, the laws would be entirely different—not to mention if he lived in neighboring Saxony.

German unification officially brought emancipation, but Jews were still effectively barred from advancement in the officer corps, the civil service, and other areas. Moreover, as Sorkin notes, emancipation wasn’t quite complete and was very tenuous: Judaism retained an “inferior status” vis-à-vis Christianity, some legal discrimination persisted at the local level, and Jewish communal politics continued to focus on the preservation of newly acquired rights. The events of the 1930s, to which I will shortly return, would show just how fragile these rights really were.

But it wasn’t in Germany alone that emancipation was ambiguous. Take the very different case of the Ottoman Empire, which Sorkin describes ably. During the 16th and 17th centuries, despite their status as dhimmi—tolerated non-Muslims—Ottoman Jews constituted the world’s most numerous and wealthiest Jewish community. They, along with Ottoman Christians, were officially granted legal equality in 1839—a reform that was applied partially in some parts of the empire and not at all in others. Subsequent edicts, in 1856 and 1865, affirmed Jews’ equality with Christians and Muslims while simultaneously solidifying their separate status as members of the organized Jewish community.

But the true paradox of Ottoman emancipation, which Sorkin notes only in passing, is that it didn’t necessarily benefit Jews. The reforms of which emancipation was a small part combined with other factors to deprive Ottoman Jews of the economic niche responsible for their former prosperity. In Germany, France, and elsewhere, the removal of legal disabilities led to, or at least coincided with, Jewish embourgeoisement. By contrast, the sultans’ reforms did nothing to slow Ottoman Jewry’s declining economic fortunes and may even have hastened them.

Little of this should be surprising to experts in the field—even if it adds much new detail in certain places—but, by putting all this information in one place, Sorkinsucceeds in showing just how complex, hesitant, and piecemeal the process by which Jews achieved legal equality really was and that this was so throughout and beyond Europe. The result is an exceptionally impressive work that required much original research, the synthesis of many decades of previous scholarship, intervention in several burning historiographic controversies, and the organization of this mass of historical material in a way that is analytically perspicacious.

As for Sorkin’s argument that emancipation ought to remain one of the crucial issues of modern Jewish history, I doubt many of his fellow scholars would disagree. But it does not follow that everything else, including the murder of a third of the Jewish people and the creation of a Jewish state after nearly two millennia of exile, are “epiphenomena”—mere side effects of the big story—even if they are, at the same time, “colossal.” Simply put, the Holocaust, Israel, and emancipation are all historic big deals in their own right.

Setting Sorkin’s hyperbole aside, it’s worth pausing for a moment on the argument that the Shoah ought to be understood in terms of emancipation. Sorkin puts it thus:

The Nazis put the revocation of emancipation front and center. Careful to maintain a semblance of legality, the Nazis abrogated citizenship as the requisite first step to exclusion from the economy, confiscation of property, expropriation of labor, and, finally, with war, deportation and murder. . . . When the Nazis came to power in 1933 the sole document that outlined Jewish policy focused squarely on emancipation. . . . The Nazis peeled away the Jews’ rights layer after layer in an almost exact reversal of the emancipation process. Dis-emancipation inverted emancipation’s structure.

All this is true and worth consideration in light of the striking fact that the emancipation of German Jewry had concluded less than 70 years before. But in the next few pages, Sorkin endeavors to describe the Holocaust solely in terms of emancipation, which simply won’t work.

If the Third Reich had collapsed in 1938, any discussion of Hitler and the Jews could indeed be subsumed into a conversation about emancipation and its ambiguity. But “dis-emancipation” in no way explains the unprecedented wholesale murder of Jews that began in 1941. It can’t even explain Nazi policy from 1938 to 1941 when Germany prevented Jews from emigrating, began deporting them eastward (as Sorkin notes), and (as Sorkin neglects to note) began unsystematically starving to death or murdering them in significant numbers.

Of course, Sorkin mentions the more systematic slaughter that began in 1941, but he concludes this section bizarrely:

In the end, the Nazis deprived Jews of the right of residence they had gained during the protracted emancipation process or even earlier as a privilege in corporate society.

In the end, the Nazis killed them. Despite Sorkin’s best efforts to show otherwise, the Shoah is more than just another episode in the back and forth of Jewish legal rights in Germany.

So much for the first epiphenomenon. What of the second, the establishment of Israel? Historians have long agreed that the rise of Zionism can’t be disentangled from the real and perceived failures of emancipation. Indeed, Leon Pinsker, author of the first clear Zionist manifesto, titled his work Auto-Emancipation to signal just that. But Sorkin also wants to convince us that emancipation is everywhere incomplete, even in the Jewish state. Yet all he can muster on this score are feeble gestures: the State of Israel doesn’t recognize non-Orthodox denominations on an equal footing with Orthodoxy. Mizrachim and Israeli Arabs (or, as Sorkin calls them, “Palestinian Israelis”) have suffered discrimination. And then there is the situation of the Palestinians themselves.

In a similar fashion, Sorkin asserts that, even in liberal and tolerant America, emancipation is only partial. The chapter on the subject makes much of attitudes toward the Holocaust, Jews’ migration to the suburbs, and even the “demonstrable retreat from the New Deal’s ambitions of . . . social welfare” after the “Cold War ‘anti-Communist’ attack on the New Deal traduced such programs as ‘communism.’” All of this culminates in a critique of American Jews for their readiness to sit back and enjoy their emancipation in a country where others supposedly lack it. It’s hard not to see where Sorkin’s sympathy lies when he sums up American Jewry’s “fundamental dilemma” of the post–World War II era:

Now counted “among the primary beneficiaries of the American promise,” Jews had to resolve the fundamental dilemma of their relationship to the status quo: Should they defend that privileged position at whatever the cost to other groups or advocate a capacious and inclusive America that could bring those privileges to all its members? How would organized American Jewry and especially their leaders construe the perennial question, “is it good for the Jews?” Would they understand it as a parochial question exclusively about Jews and their favorable position in society? Or would they understand it broadly as a query about promoting a society concerned with the welfare of all its members, Jews included?

Sorkin does not tell us why a defense of Jewish equality should impose any cost on other groups.

While some of Sorkin’s complaints about Israel are exaggerated or miss the mark, the real problem with his argument runs deeper. Even if Israel were both a repressive theocracy and an apartheid regime, that wouldn’t have anything to do with Jewish emancipation. Once Jews have a state of their own, the question of emancipation becomes irrelevant. Would we speak of Catholics in old-regime France as unemancipated because of the status of Jews? Of course not. Nor would we say that Louis XV’s suppression of the Jesuits was a setback for Catholic emancipation in France. A Jewish state, just as a Catholic state or a Danish state, must wrestle with the questions that have faced every majority people throughout history: What should the status of minority peoples be? How much equality should there be among the majority? What is the relationship between religion and state? How should the state handle intrareligious squabbles? Israeli Jews face them not because their emancipation is incomplete but precisely because they live in a post-emancipatory situation.

Sorkin’s arguments about American Jewry are even more tendentious. While he seems to be under the impression that Commentary magazine represents the mainstream of Jewish public opinion, the fact is that Jews, as they did in FDR’s day, overwhelmingly vote Democratic (as the last election has yet again demonstrated), support a robust social safety net, and even tend to favor affirmative-action policies that amount to a de facto quota on Jews in the universities. Migration to the suburbs, meanwhile, is a sign of the integration that follows emancipation: freed from residency and occupational restrictions, Jews left ethnically homogenous working-class neighborhoods and moved into more mixed middle-class ones. The place of the Holocaust in the American Jewish imagination certainly reveals much and probably deserves criticism, but so what? Even if all of these complaints rested on solid empirical grounds, they merely show that American Jews, like their Israeli cousins, have earned Sorkin’s disapproval, not that their emancipation is only partial.

Aside from serving as a cudgel with which to beat those Jews who don’t live up to his lofty moral ideals, these arguments support the last two theses of Sorkin’s emancipation: that emancipation is “ambiguous and interminable” and, thus, that “Jews everywhere continue to live in the age of emancipation.” But are Jews anywhere in danger of being deprived of their rights? In lieu of presenting any concrete evidence that this is so, Sorkin simply tells us that emancipation will never be complete so long as Jews everywhere haven’t taken on his own political preferences.

It would be wrong to say that, in 2020, Jews in either Israel or the diaspora are without flaws or face no risks. But, even if the nightmare of a Corbyn victory in the UK’s most recent election had come about, it’s hard to imagine Jews would have been restricted from holding office, or been confined to particular neighborhoods, or have to pay special taxes. (Tellingly, Sorkin never mentions the rise of Corbyn in Britain or other similar phenomena.) Nor could France’s National Front, in the unlikely case that it won an electoral victory, be expected to go so far. Nor have the far-right governments that have come to power in Central and Eastern Europe made any such steps.

Likewise, the physical and rhetorical assaults on American Jews, whether on college campuses or in the streets of Crown Heights and Jersey City or the synagogues of Pittsburgh and Poway, haven’t been coupled with proposals to restrict Jews’ civil rights. By comparison, the Hep-Hep riots, which swept through Germany in 1819, were a pointed response to emancipation. Today, the status of Jews as citizens seems entirely irrelevant to all but the craziest fringe of antisemites. This is not to say that it is preferable to be murdered in a synagogue than to have to listen to a debate about whether Jews should be allowed to purchase real estate, only that the battle over legal emancipation has ended, and the war against the Jews has taken on new forms.

While Sorkin is correct to say that, for much of the 19th century, “organized political anti-Semitism’s primary goal was to restrict or abrogate emancipation,” one might better see contemporary antisemitism as a post-emancipation phenomenon whose aim is no longer to withdraw legal privileges or impose restrictions.

One can argue at length about

the transformations of Jew-hatred since 1815 (or since 2015), the wisdom of

various remedies, and where the greatest present threats to Jews come from. But

I think it’s safe to say that any questions today about Jews’ legal status

are, well, epiphenomena compared

to the graver issues facing the Jewish people. In that sense, contra Sorkin,

the age of emancipation has indeed ended.

Suggested Reading

Emancipation and Its Discontents

How a small, marginal community of Moravian Jews grappled with the challenges modernization and secularization brought to European Jewry.

Montefiore and the Politics of Emancipation

More than a shtadlan.

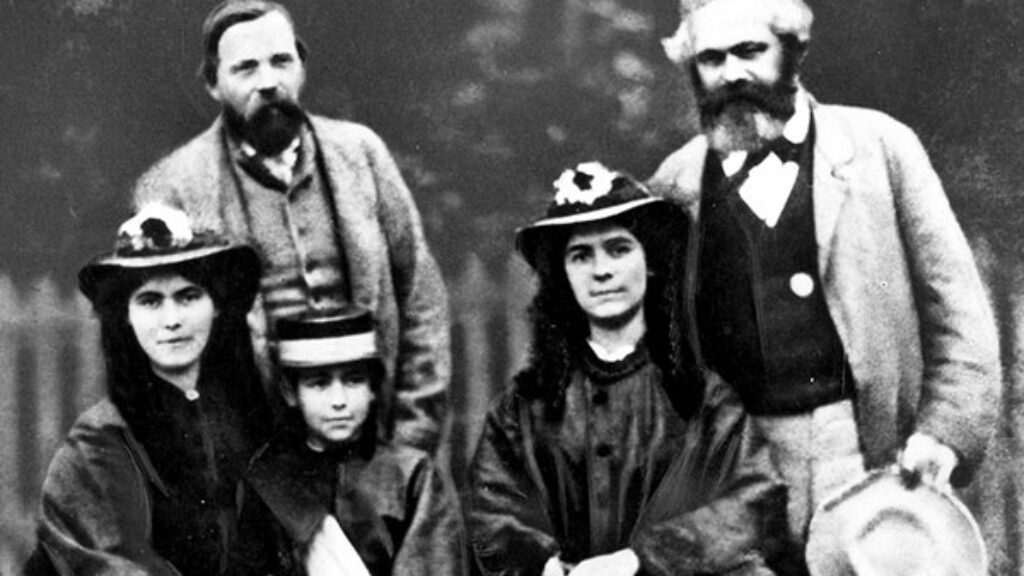

Marx and the Jewish Fingerprint Question

Are there hints about Marx’s thoughts on Judaism in his writing, and if so, what do they say?

The Joy of Being Delivered from Jewish Schools Results in a Stiff Foot

Before he became a brilliant, radical, and disreputable Enlightenment philosopher, Solomon Maimon was a miserable cheder student.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In