Straightening Out the Menorah

Chabad’s campaign of public menorah lightings began in San Francisco, in 1975. Two local Lubavitcher rabbis, Chaim Drizin and Yosef Langer, met with the program director of the local public television station and Bill Graham, San Francisco’s famous Rock and Roll impresario (and Holocaust survivor, born Wulf Grajonca in Berlin), and came up with the idea of erecting a twenty-five-foot-tall mahogany menorah in Union Square on Hanukkah. Although the menorah has returned to Union Square every year since then (along with the eighty-three-foot-tall Macy’s Christmas tree), its shape—giant bent L-shaped arms emerging sideways and then upwards from a center column—is now unique in the vast landscape of Chabad menorahs. Just a few years later, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, established the now-iconic Chabad menorah: eight straight arms, pointing upward diagonally, four on each side, emerging from an unadorned central pole. This austere figure is now familiar from hundreds of public lightings around the globe. Like some other Chabad traditions, it seems to be a charming ritual idiosyncrasy until, beneath the surface, you discover a grave point of doctrine.

In truth, not everyone has been charmed by these straight-limbed Chabad menorahs. In 2007, when the Chabad lightings in Israel were getting into high gear, the Israeli critic Ariel Hirschfeld wrote in Ha’aretz that these menorahs:

Exude melancholy, carelessness, above all—ugliness . . . metal tubes tied haphazardly . . . [all this when] the menorah is the most significant visual image that Judaism gave the world, its famous form, carved on Titus’s arch being the most concrete picture we have of the early history of the Jewish nation.

Actually, the fact that the classic image of the Temple menorah, with its gracefully curved arms, comes from the famous triumphal arch in Rome (which depicts the ignominious defeat of the Jews and the sacking of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE) was a strike against considering it either authentic or beautiful in the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s opinion.

In a talk, or sicha, delivered in 1982, Schneerson drew upon the great Yemenite-Israeli scholar Rabbi Joseph Kafih’s edition of Moses Maimonides’s Commentary on the Mishna, which reproduced Maimonides’s own hand-drawn sketch, or diagram, of the menorah as described by the mishnah. As Kafih noted, this drawing was attested to in the best Yemenite manuscripts, as well as the famous autograph manuscript held in Oxford (Bodleian Ms. Poc. 295), and it contradicted the “fake” image on the Arch of Titus, which the founders of the State of Israel had ignorantly chosen as the seal of the new state.

In an extended digression to the mishnah’s remark that menorah’s limbs and lamps must all be intact for any of them to be valid (Menahot 3:7), Maimonides says that he has seen fit to draw the shape or form of the Temple menorah, the tradition for which “is in our hands,” in particular the relative placement of the cups, bulbs, and flowers that adorn the menorah. Here is Maimonides’s own drawing:

This is striking. Early Jewish oral traditions preserved dauntingly complex facts and customs, and nothing was more in need of preservation than the memory of the destroyed temple. If such a tradition surfaces in an author as knowledgeable and sober minded as Maimonides, surely that signifies something. And although Maimonides wrote, for instance, that “the intention in this drawing is not to show exactly how a cup looked in truth,” his own son Abraham took his drawing literally. In a passage of great importance to both the Rebbe and Rabbi Kafih, Abraham wrote that the branches of the menorah “extend from the central staff of the menorah to its height in a straight line, as depicted by my father, of blessed memory, and not rounded as depicted by others.”

So Schneerson and Kafih would appear to be correct about Maimonides’s opinion on the correct shape and construction of the menorah. And Maimonides may well have possessed a valid tradition regarding it. Perhaps the menorah depicted on the Arch of Titus was a conscious or unconscious romanization, as it were, of Judean ritual art.

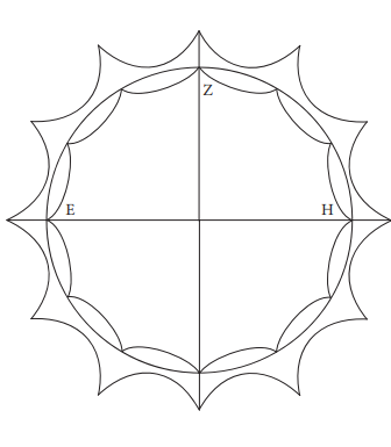

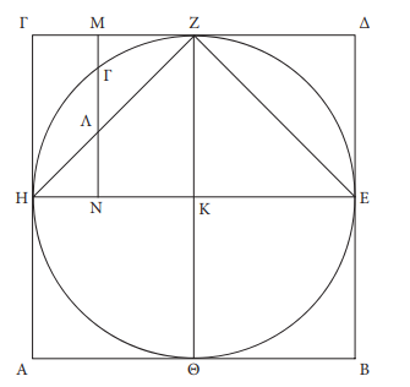

But what does Maimonides’s drawing really signify? Until recently, scientific illustrations were neglected by historians but, when we started paying attention to them, it turned out that they had their own surprising stories to tell. Let us look, for instance, at the Archimedes Palimpsest, a Byzantine copy of some ancient Greek mathematicians’ works, which was copied in Constantinople, around 975. Here is a diagram of a circle with polygons circumscribed and inscribed around and inside it:

Surprisingly—to us, at least—the edges of the polygons are each represented by the arc of a circle.

Conversely, in another diagram we see a square enclosing a circle, both of them enclosing a parabola. But this last parabola is represented by a triangle:

Medieval diagrams were simply different than ours. They were not expected to represent relative size—“this is twice that”—or angles—“this is a 60-degree angle.” (Indeed, how could you expect to represent such facts correctly, copy after copy, before print?) They were often suggestive of such relations, but the only thing they definitely represented was the topology—what intersects with what, in which order things are located.

When it was convenient to an ancient or medieval scribe, he was free to represent a straight line by an arc and vice versa. For instance, each side of the above inscribed polygon should meet the circle exactly twice: this can be represented by arcs. The parabola meets the circle at three points, which the triangle does just as well.

Jewish intellectuals, including Maimonides, fully participated in the scientific exchanges of the Mediterranean. In the French National Library today, one may consult about fifteen hundred Hebrew manuscripts, mostly from the Middle Ages. About a hundred are dedicated to mathematics and astronomy. There are probably more medieval Hebrew astronomical manuscripts than there are medieval Jewish copies of the Talmud (of course, Hebrew astronomy texts were never burned by the Church). As for Maimonides, in mathematics as in all else, he was much more than a novice. Y. Tzvi Langermann was the first to recognize that Maimonides made original contributions to the study of conic sections (that is, figures such as the parabola), in a commentary he wrote on Ibn al-Haytham’s Completion of the Conics of the ancient Greek Apollonius. It doesn’t get any more advanced than that. Maimonides was immersed in the scientific culture of his time and his diagrams, almost certainly, would have been similar to those of other medieval scholars.

In modern scientific illustration, the goal is usually pictorial. It would therefore be valid to read off Maimonides’s illustration as representing a menorah of diagonals, had it been drawn in, say, the twentieth century (it is worth noting here that Schneerson was, among other things, a twentieth-century engineer). But it was drawn in the twelfth century. Illustrations back then, especially as drawn by mathematically trained authors, tended to be schematic and therefore did not carry detailed, pictorial meaning. Thus, the straight lines in Maimonides’s diagram need not represent straight lines.

The principal purpose of the drawing, Maimonides emphasized, was the relative position of the ornaments on the branches—the menorah’s topology, as it were. The lines in Maimonides’s drawing were literally just the pegs—a coat-hanger, so to speak—on which he drew schematic representations of ornaments, which themselves were abstract (decorative cups become inverted triangles, and so on).

And what of the testimony of Maimonides’s son Abraham? It is certainly counter evidence to my interpretation of Maimonides’s drawing, but how strong is it? Three bits of biographical context suggest that it is less strong than one might think. First, Abraham was the son of his father’s old age. Second, although he did follow his father in becoming a rabbinic scholar and religious thinker, an accomplished physician, and a community leader, Abraham was not a part of the medieval scientific world in the way his father was. Finally, Abraham frequently insisted upon the literal truth of his father’s texts, a tendency which is not uncommon among the children of distinguished parents. In this case, I would guess that his laudable filial piety resulted in overinterpretation. Here I would appear to be in agreement with Steven Fine, author of the definitive history of the menorah, who writes that “it is not at all clear to me that straight branches were Maimonides intention,” Abraham’s testimony notwithstanding.

So, the Chabad menorah is likely based on a misinterpretation of Maimonides’s drawing. But this is not the end of the story. What Schneerson understood perfectly well was that pictures are never neutral and always depend on a visual code. Why do we have so many images of the round-branched menorahs? Because—to quote Ariel Hirschfeld once more—“the menorah is the most significant visual image that Judaism gave the world, its famous form carved on Titus’s arch.” There are other sources for the round-branched menorah as well but, ultimately, it all goes back to that Roman carving. This made Schneerson rightly suspicious. Indeed, the representation on the Arch of Titus is too elegant, and in a very Greco-Roman way.

The curves of the menorah fit within the overall dynamic swerve of the procession depicted on the arch; the most damning detail, as Kafih and others noted, is in the base of the menorah, which carries pictures of some weird Roman myth, sea-dragons and all—what a pagan would expect to see on a sacred monument and surely an impossibility in the Jewish temple. The artist in charge of Titus’s Arch transformed the menorah through his own visual language.

The original light of the menorah is refracted, so to speak, through two separate Greek prisms: the prism of Greek relief art, in Titus’s Arch and the prism of Classical mathematics, in Maimonides’s manuscript.

As it happens, abstract expressionism was largely created by Jewish peers of the Rebbe. They moved in very different circles of post-war New York than the Rebbe and his hasidim, but, as any Chabadnik will tell you, they were equally Jewish. And all were heirs to a tradition deeply suspicious of the graven image. At that time and place, they also shared a fascination with science, technology, the American promise, and a dread of the infernal evil so recently visited upon the Jews. The monumental shapes of Mark Rothko, for instance, simultaneously celebrate the modern—austere, magnificently geometrical—and recoil from representing it.

The Chabad menorah does something similar. It cancels all ornamentation—those pleasing Jewish alternatives to Christmas tree decorations—and replaces them with an austere geometric form, breathing the scientific-philosophical purity of Maimonides. Geometrical plainness, perhaps, is the point. When we look at eight straight lines, we can imagine an abstract network of relations in space, where the very categories of “straight” or “curved” lose meaning.

The point of the medieval diagrams was to allow an imperfect image to be the precise representation of a mathematician’s original thought. At this level of representation, all shapes are brought together: the Chabad contraption of metal tubes; the image carved on Titus’s Arch; the ornamental chanukiyot in Jewish homes; finally, that lost monument of ancient Jerusalem—recoverable only in this realm of pure abstraction.

Read Eli Rubin’s thoughtful response about the Rebbe and art here.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

The exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks on Jewish power and politics is illuminated by the history of Hanukkah.

Hanukkah’s Confounding Miracle

How Hanukkah became a holiday of many miracles and none.

As the Story Goes: Hanukkah Spears, Cheese, and Goblins

Where did all the Hanukkah stories go?

In Memory of Judah Maccabee

That Judah, the great victor of the Hanukkah story, ultimately died fighting the Seleucids is something that surprisingly few Jews know. And were the Maccabees actually underdogs?

Joseph

An important ally to Maimonides on the nature of the branches of the Menorah is Rashi himself.

See Rashi (Exodus 25: 32): "Extending from its sides: 'From its two sides, diagonally...'"

Rashi conrinues to descrie the length of the branches, each shorter than the other.

This is a powerful ally to the Rebbe and is in accordnace with Maimonides.

gershon hepner

THE CURVES THAT ARE STRAIGHTENED

When we’re are at home and are not thinking about buying

gifts for our family and friends, we celebrate the best of all

our memories, how we miraculously still survive, relying

on God. helped by the heroes who made possible this festival,

that’s celebrated in some public places with an imitation

of the menorah that has not got seven branches but has eight,

unlike the curved ones on the arch of Titus. Following the illustration

made by Maimonides, Chabad’s menorah’s branches are not curved but straight.