Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

In his response to Rabbi Shlomo Riskin’s review of his book, Not in God’s Name, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks invokes the religious failure of the Hasmonean dynasty:

[N]either will I defend the toxic mix of religion and politics that has been the downfall of every culture that embraced it: Judaism in the late Second Temple period, Christianity in the 16th and 17th centuries, and radical political Islam today.

The separation of church and state, he argues, derives from the Bible’s insistence upon divesting the monarchy of its sacred aura. When the Maccabees turned priests into kings, they ignored this central biblical teaching, thus courting spiritual disaster. Strikingly, in his rejoinder Rabbi Riskin also invoked the Maccabees, but for more or less the opposite reason:

[P]ower is religiously significant if and only if it is used to religiously significant ends. This is why . . . our sages added the al ha-nissim prayer to commemorate the victories of the Maccabees on Hanukkah.

Rabbi Riskin’s biblical ideal is “a constitutional nation-state . . . integrally related to the Abrahamic vision” of ethical monotheism. “Without power,” he argues, “how can the chosen people protect the powerless against their exploiters? And, of course, without power, how can the chosen people protect themselves?”

Rabbi Sacks is, of course, the former chief rabbi of Great Britain, and Rabbi Riskin is the founding chief rabbi of the Israeli settlement of Efrat, so it is tempting to map their debate over Jewish power and their attitudes toward the Hasmoneans onto their respective locations. This is not quite fair since Rabbi Sacks is a Religious Zionist—and Rabbi Riskin is very far from a zealot. Nonetheless, their exchange does echo an ancient debate over religion, power, the nature of the Maccabees’ victory, and the legitimacy of the Hasmonean dynasty that divided thinkers along Israel-diaspora lines.

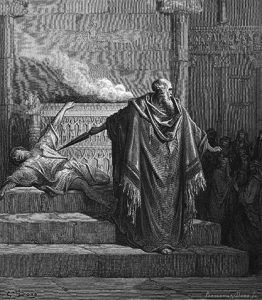

The earliest description of the Maccabean revolt is in 1 Maccabees, which was written in Hebrew only a few decades after the Maccabean victory in 164 B.C.E. Preserved by the Church in its Greek translation, 1 Maccabees describes the priest Mattathias’s first heroic act as the murder a fellow Jew who agreed to offer a pagan sacrifice under pressure from a decree by the Seleucid rulers. In narrating this story, the author makes a telling comparison:

Thus Mattathias burned with zeal for the law, as Phinehas did against Zimri the son of Salu. Then Mattathias cried out in the city with a loud voice, saying: “Let everyone who is zealous for the law and supports the covenant come out with me!”

Phinehas was the priest who killed an Israelite chieftain engaged in an idolatrous, carnal, public desecration, and Mattathias’s cry echoes that of Moses to the Levites to arm themselves to attack their fellow Israelites after their worship of the golden calf. Mattathias’s act is thus placed in line with these earlier, paradigmatic acts of Levitical violence that found their first expression in Shimon and Levi’s massacre of the Shechemites in retaliation for the rape of their sister Dinah.

The praise for Phinehas’s zeal, taken for granted in 1 Maccabees, is far from universal. Already in Numbers 25:12, God grants Phinehas a “covenant of peace,” which one can understand as condoning his act but also limiting it to a one-time event, never to be repeated. The Talmud states further that Phinehas deserved to have been put under a ban if God had not made such a covenant. Significantly, when the story is alluded to in Psalms, violence goes unmentioned: “Phinehas stood up and judged (vaye’fallel)” (Psalms 106:30). The Talmud takes this to mean that Phinehas argued with God on the justice of sending a plague upon the nation. All this stands in contrast to 4 Maccabees 18:12, which lists Phinehas’s violent zeal as part of the core curriculum a good father teaches his sons. Thus, at least some Second Temple writers in the Land of Israel saw Phinehas’s zealotry as a model, while the post-Temple talmudic rabbis, mostly in Babylonia, took advantage of biblical ambiguities to limit and transform his act toward peaceful diplomacy.

The Hasmoneans themselves had no shortage of detractors even in their own days and more so after their downfall in 63 B.C.E. Josephus reports that the Pharisees reviled John Hyrcanus, the grandson of Mattathias, and insisted that he should be content with the monarchy and leave the spiritual leadership to a descendent of the Zadokite family, the legitimate high priestly dynasty, thus restoring the biblical separation between political and priestly power. The Babylonian Talmud echoes a similar complaint against Hyrcanus’s son, Alexander Yannai. Both sources tell the story of Pharisees pelting Alexander Yannai with etrogim (citrons) one Sukkot, leading to a civil war that lefts tens of thousands dead. We should recall that at the time they told this story both Josephus and the rabbis sought peaceful relations with the Romans and wanted to discourage any zealous behavior by their co-religionists. It is not surprising that they did not look back in admiration or nostalgia to the Hasmonean kings.

We can see this hatred of Hasmonean power on coins as well as in texts. A bronze peruta coin struck during the reign of Alexander Yannai includes his Hebrew name and reads “Yehonatan the High Priest and the Council of the Jews,” indicating that the Hasmonean high priest worked with some kind of a representative body.

A slightly later coin reflects Alexander Yannai’s self-promotion. It reads “King Alexander” in Greek around an anchor on the obverse and on the reverse “Yehonatan the king” in Hebrew within the spokes of a star diadem. The “Council of the Jews” has disappeared.

A third coin shows how controversial this was. This peruta originally read “King Yannai,” as in the second coin, but was then overstruck to read “Yehonatan the High Priest.” Apparently, popular pressure forced this reversal.

The groups attacking the Hasmoneans, mostly Pharisees, did not object to Jewish sovereignty, but they did object to the Hasmonean consolidation of political and religious power. The former was to be the domain of the Levites and priests, while kingship was the exclusive inheritance of the tribe of Judah. (More than a thousand years later, Nachmanides would attribute the rapid fall of the Hasmonean dynasty to their illegitimate consolidation of priestly and monarchical power).

The books of Maccabees (there are four of them) inspired many generations of religious zealots, including the Bar Kokhba rebels and Christian martyrs. The early rabbis rejected these books from the canon not only because of the late date of their composition but likely also because they wanted to suppress their revolutionary message. When it came to the celebration of Hanukkah, however, the rabbis found themselves in a quandary. On the one hand, they too yearned for Jewish national sovereignty; the success of the Hasmoneans, even if short-lived and imperfect, could not be denied. On the other hand, their antipathy to the combination of kingship and the priesthood and the subsequent Hasmonean corruption forced them to reject the history presented in the books of Maccabees.

The rabbis promoted the celebration of Hanukkah but not as a glorification of a military victory. Instead, it commemorated the miracle of the small cruse of still-pure Temple oil that lasted eight days, an event that had not been mentioned in any earlier source. It is true that the al ha-nissim prayer recited on the holiday includes a reference to battle, but God is the only fighter mentioned in the text. This prayer, first attested in geonic works, includes these memorable words of gratitude: “You delivered the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the few, the wicked into the hands of the righteous.” Here again, the human strength of massive armies is equated with evil, and it is only within the feeble minority that one finds righteousness and ultimate victory. The classic rabbinic Hanukkah was an apolitical and demilitarized celebration of hope and trust in divine providence and protection, not priestly violence and national sovereignty.

Does the argument between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks recapitulate the ancient disagreement between the early rabbis and the defenders of the Hasmoneans? Certainly there are echoes of these historical positions in Rabbi Sacks’s rejection of any mixing of religion and politics as “toxic” and Riskin’s insistence upon the inescapable necessity of political power wielded by a sovereign Jewish state. But Riskin is certainly not an advocate of any modern version of priestly violence. In fact, in 2011 he wrote a brilliantly angry “Hanukkah Letter to the Hilltop Youth”:

You consider yourselves the new Hasmoneans, the Maccabees who do not bow their heads before the Hellenizing priestly establishment, which today, you believe, wears the uniform of the Israel Defense Forces. Because you are convinced that all your deeds are for the sake of heaven, you will never admit that you have sinned.

Riskin may be more likely than Sacks to look to the Maccabees or other biblical and Second Temple models as models of Jewish power, but he is certainly not an advocate of Mattathias-like violence in the modern world.

Theodor Herzl concluded the The Jewish State with the prediction “the Maccabees shall rise again.” As we light the Hanukkah candles and recite al ha-nissim, perhaps we can appreciate the rabbinic strategies of powerlessness and submission to a divine plan while, at the same time, remembering the Maccabees as models of political initiative and how (and how not) to confront the transition to Jewish statehood.

Suggested Reading

Hanukkah’s Confounding Miracle

How Hanukkah became a holiday of many miracles and none.

Israel at 70: The Bonus Book List

Last week we asked 70 leading Israeli and American thinkers to recommend the best books about Israel. Here are some fascinating and quirky outtakes.

The Angel and the Covenant

Hurwitz’s ideal Jew is the rabbinic scholar who is also knowledgeable about, and open to, modern science.

Camp Mountain Lake, 1977

The picture-taking began when he was still a little kid, at Camp Mountain Lake in North Carolina. The owners of the camp remember a chubby kid, not very athletic, and the camera was a way of making friends.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In