As They Are

There are hardly any women in A Vanished World, Roman Vishniac’s classic postwar album of the ill-fated European Jews he photographed in the 1930s. With their nostalgic and elegiac quality, those pictures—more black than white, more religious than secular, and more masculine than feminine—established a way of seeing and photographing Orthodox Jews, especially Hasidim, as a pious, almost premodern, cadre of men and boys.

In the decades since, photographers have continued to draw a line between the peculiar world of Hasidic men and the modern people who view their images. A 2012 Israel Museum exhibit entitled “A World Apart Next Door: Glimpses into the Life of Hasidic Jews” highlighted the inaccessibility of even neighboring Hasidic communities and trained its focus largely on Hasidic men. When Hasidic women did appear in the exhibition, it was in ethnographic treatments of custom and couture. One recurring theme was the mitzvah tantz, a ritual dance in which a Hasidic bride, her face occluded by a thick napkin, holds one end of a long, decorated sash while a Hasidic Master, dancing deliberately, holds the other end. In such charged imagery (which replicates the perspective of the Hasidic men who intently watch the scene), the veiled woman is almost literally present and absent, more a symbol of the Shekhina—the cherished, feminine facet of God—than a flesh-and-blood human being.

To be fair, photographing Hasidim isn’t easy, and photographing Hasidic women is even harder. Vishniac claimed that Hasidim were so resistant to the medium that he was forced to deploy a hidden camera. He was exaggerating (Vishniac was a self-mythologizing fabulist), but many Hasidic groups are still camera shy. What is more, strict rules of modesty and an insistence that Hasidic women should be kept out of the public eye further complicate the task of taking their pictures.

Unlike their husbands, Hasidic women are not, in practice, followers of the rebbes who lead the courts. Thus, the word “Hasidos”—the feminine plural of Hasidim (“devotees”)—is never used within the community to describe its female members, perhaps leading to the misimpression that they are somehow less Hasidic. But Hasidic women are influential not merely in the performance of traditional domestic duties but in shaping the spiritual tone of the Hasidic home. Within that realm, and in women’s spaces like the women’s balcony, Hasidic women have carved out a distinctly feminine space, one that has, until recently, rarely been depicted in photography.

For almost two decades, Polish photographer Agnieszka Traczewska has been taking pictures of Hasidim around the world: in her native Poland, in neighboring Ukraine, and farther afield in Western Europe, Israel, and North and South America. Her commitment to geographic breadth mirrors a commitment to working across the gender divide. By patiently cultivating friendships with Hasidic families over the span of years, Traczewska has been able to photograph Hasidic men and women alike (her photo-essay of Hasidic men working in a tefillin factory in Poland appeared in these pages in Spring 2023). And her close relationships with her photographic subjects have helped Traczewska avoid exoticism, despite the barriers she has had to overcome as a non-Jew and a woman.

Traczewska aims to photograph Hasidic women as they are, beyond the ethnographic gaze of the outsiders who, curious about Hasidic life, will ultimately view these pictures. Some of the photographs published here return to older themes in Hasidic iconography, like weddings and Jewish holidays, but they do so with fresh eyes. Remarkably, women are foregrounded, while men, if they appear at all, are incidental. Thus, we are treated to scenes of sisterly celebration in dining rooms, city streets, and even on the beach.

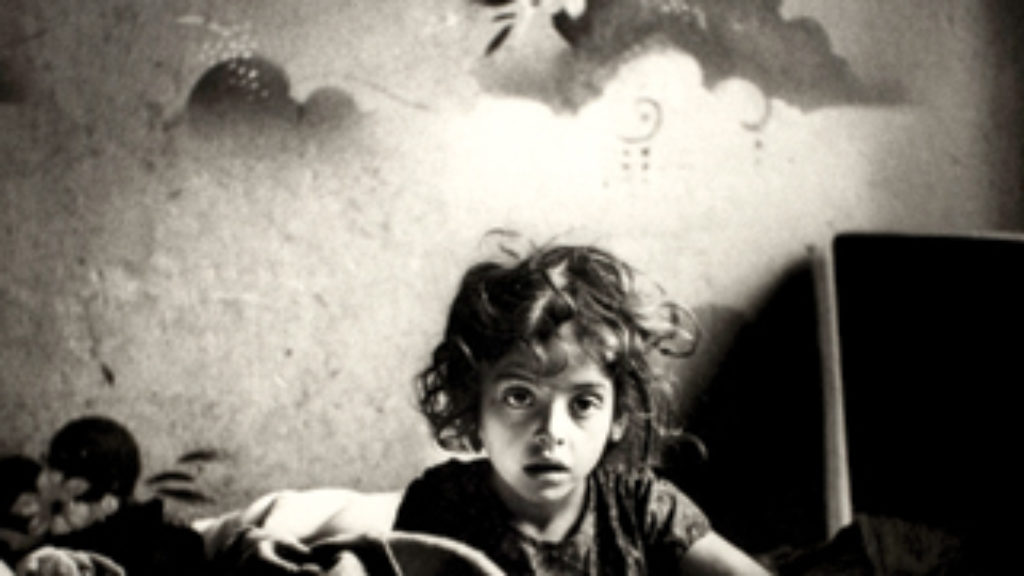

Traczewska’s unique portraits disregard the ultra-Orthodox reticence about depicting women’s faces and focus on the dignity, dedication, and tenderness of middle-aged Hasidic women. Another photograph, of a girl on Purim, uses the exaggeration of costume to depict the precision that governs Hasidic aesthetics.

Hasidic Jews generally separate men and women and insist that they have different, complementary roles in Jewish life. This antiegalitarianism creates distinct, gendered forms of religious expression, which Traczewska’s pictures make legible. Thus, in a photograph taken at Jerusalem’s Western Wall, a woman wearing a dramatic wig and stylish coat lifts her head heavenward, enraptured in intense prayer. In another picture, also taken in Jerusalem, an elderly woman displays an unusual record of her hospitality: an impossibly long sheet listing the names of the many guests she’s fed at her Shabbes table, unfurled like a scroll.

Notwithstanding the parallel spiritual lives of Hasidic women and men, Hasidic marriage is, in essense, a spiritual collaboration between husband and wife. In the final image, it is Avraham Yaakov Epstein who lights the Hanukkah lamp, but it is the smile of his wife, Sara, that really makes it glow.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Bind Them as a Sign: A Photo Essay

A Hasidic-owned, bicycle-powered tefillin factory in Krakow, Poland.

The Vanishing Point

A new exhibit explores the vanished world and unseen photographs of Roman Vishniac.

From Place to Place in Search of a Place: Reading Agnon in Berlin

Far from his family, and searching for a sukkah, Shai Secunda found himself following Shai Agnon’s footsteps through the city of Berlin.

Like a Pharaoh

I had attended many Yiddish classes before, but not one in which I was the only Jew in the room.

Howard S

One thing that is missed in articles about life among the Ultra-Orthodox, the "Frum" folk, and this is an excellent article to be sure, is that, like acolytes living within any cult environment, be it the Old Amish. the Latter Day Saints, the Jehovah's Witnesses, or any of the various Ultra-Orthodox groups, is the fact that most of the members of those cults are quite happy with the lives they are living, the demands being made on them, and their specific role in their own society. And the fact remains that so few of these people enmeshed in their particular cult environment end of leaving. Knowing what to wear, what to eat, what to think, how to organize your home and your day to the most minute detail - these are very protective and comforting to the cult member. We human beings are social animals, and finding our place in whatever society fate has put us is a satisfactory way to get thru the struggle of daily life for most people.