From Place to Place in Search of a Place: Reading Agnon in Berlin

Last spring, I became inexplicably fixated on a distant, autumnal detail: whether I would be able to build a sukkah in Berlin. An unexpected invitation to spend a fellowship year working on my next book at a distinguished institute near the wooded edges of the city was almost too good to be true. Yes, it was far from my family in Israel, but it was closer than the Hudson Valley in upstate New York, where I normally teach. So, in the fall, I packed up to leave, still worrying about whether I would be able to build a temporary dwelling outside my new temporary dwelling. I squeezed into my suitcase two hefty dictionaries, a few critical editions of rabbinic texts, and a tattered copy of Agnon’s Berlin novel Ad Hena (To This Day).

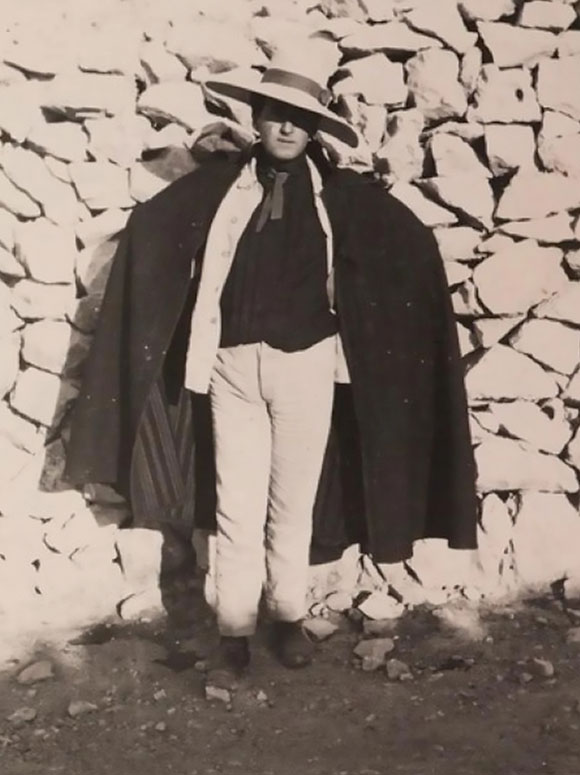

Shmuel Yosef—known as “Shai” after his initials—Agnon was the leading literary chronicler of the waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine in the early twentieth century, in which he took part. He was also an unparalleled teller of tales about the charmed but doomed world left behind, especially his native Buczacz, a small town in present-day Ukraine. Germany, on the other hand, where Agnon lived from 1912 until 1924 before returning to the Holy Land, was a space in between to which he turned only toward the end of his career. To This Day was the only novel set in Germany that Agnon published in his lifetime (In Mister Lublin’s Store, also set in Germany, was published posthumously).

To This Day is a winding tale relayed by a drifting narrator autofictitiously named Shmuel Yosef who struggles to secure a decent flat in wartime Berlin (all translations are mine, though I sometimes adapt Hillel Halkin’s fine translation):

In each and every land you’ll find cities and towns, houses and rooms. Sometimes, a single man will dwell in many houses, and sometimes many men will dwell in a single room. Our story is of a man who has neither house nor room, having left the place he had and let go of the place he found. And so, he went from place to place in search of a place.

To This Day is not one of Agnon’s best-known works, nor is it widely beloved, dividing critics—at times against themselves. Baruch Kurzweil, who received a copy from the author, initially complained in a letter to Agnon of the book’s fragmentation. Just a few months later, he would sing the novel’s praises from the critical heights of the Ha’aretz literary supplement. It is not hard to see why the Israeli critic, who wrote of many things but especially the desolations of the modern age, came to appreciate a novel whose modernist meanderings at first repelled him. Kurzweil had realized that the literary device of a Jew drifting spectrally through the chaos of World War I Berlin perfectly conveyed society’s sundering.

“It’s almost impossible to believe, but Europe is again on the brink of war!” my wife’s college roommate, now a rebbetzin in Berlin, shouts over the phone. “Our community is mobilizing for a massive influx of Ukrainian refugees, and you’re worried about Sukkos plans?!”

The emails coming in from my educational hosts that spring had their own gloomy glow. COVID-19 protocols would remain in place, with stricter regulations planned for the upcoming flu season. Thanks to ill-advised energy deals cut with the Russians before the invasion of Ukraine, a German heating crisis loomed. I was heartened, however, that a remarkable group of Ukrainian scholars and dissidents from Belarus and Turkey had found refuge at my institute, even if they should have been free to continue their work at home.

Despite the portents, when I fly out of Israel, land in Berlin, and start unpacking in my furnished flat in West Berlin, a sense of expectation washes over me. I put up a pot of coffee, sit down on the living room couch, and read the opening lines of To This Day:

During the Great War I lived in the west of Berlin in a small pension on Fasanenstrasse, in a room with a balcony. The room was small, as was the balcony. But for a man like me, who knows how to contract himself, it was a place to live.

Thinking again about the upcoming holiday, I get up from the couch and walk onto the porch to inspect its sukkah viability. Alas, the balcony is covered, and one of the sukkah’s halakhic requirements is to sit squarely, vulnerably under the open sky. But it looks over a lazy canal, placid lake, and a patch of grass near verdant trees, which would be a good place for a sukkah. I sit back down, turn the page, and continue to read:

There’s a saying that even the sun dislikes living in darkness, and I suppose that’s what kept it from my room. And I, who had emigrated from the Land of Israel and had tasted its sun, craved real sunshine. Yet each time I stepped out on the balcony to warm up in the sun I had to retreat inside at once, since there was a legion of trees covered in dust that the breeze blew everywhere, as there were no street sweepers because of the war. Trees planted to make life better were only making it worse. Man is as a tree of the field. Man makes war, increasing pain and suffering, and the trees join in.

Coming across these melancholy lines in the comfort of a bright Berlin apartment breaks the conceit of reading Agnon’s Berlin novel while living there. My neighborhood is, in fact, sparklingly clean.

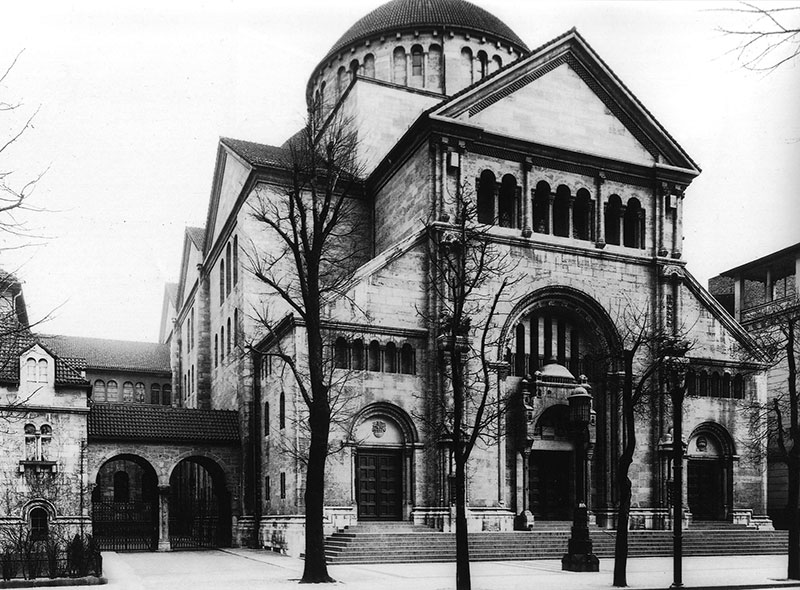

More important,the novel’s wartime city, and my contemporary one, is separated by the passage of time and untold evil and suffering, survival and renewal.Jewish Berlin today is more vibrant than it has been in almost a century. A kosher food festival I attend on my first Sunday in town is thronged by hundreds of community members. A gleaming Jewish school is in the final stages of construction. And the synagogue in which I pray echoes with vitality.

Although Agnon wrote To This Day in the immediate aftermath of the Shoah, his choice of a first-person narrator living in World War I Germany meant that there is hardly a whisper of the coming catastrophe. And yet, the book’s peculiar energy is supplied both by the spectacular violence of the First World War taking place just off site (it never reached Berlin) and the coming cataclysm of the second.

“If I wrote fiction,” one of the book’s colorful characters, Dr. Mittel, says:

I’d write a story set in the future. I’ll tell you how it would end. Germany has been vanquished and divided up by the victors. . . . All their books and works of art are burned for heating and cooking. In the end, not a page survives from all of German literature and philosophy. You say one war couldn’t do that to a great nation? One war draws another war.

It is deeply disconcerting to admit that the dynamism of Berlin—that electricity you sometimes feel when walking its streets and staring out into its darkness—is charged by the seething atrocities that lie underfoot and around the bend. Rushing to catch a train during my first week in town, I mistakenly end up instead standing at Gleis 17, a set of memorial tracks inscribed with the dates, destinations, and numbers of Jews who were transported from my neighborhood—the most beautiful in the city—to the camps.

Grey Day, by George Grosz, 1921. (Photo © Andrea Jemolo/Bridgeman Images; © 2023 Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.)

And antisemitism in the city is not a thing of the past. I come to learn this on the Saturday afternoon before Sukkot, walking back from shul with my family, who has come to spend the holiday in Berlin. When we’re just a few minutes from the apartment, a couple of young teenagers on scooters approach us from behind, yelling “Juden” as they roll by.

This, of course, is a statement of fact: we are Jews. But it is uttered with menace, which they follow with the iconic Nazi salute, performed twice, slowly, arms deliberately extended as they loudly snigger.

The execution of that symbol in this place dislodges something primal within me. It is not fear I feel but burning rage and righteous indignation. I curse them with the saltiest string of expletives that has ever passed my lips and bluff that I’m going to call the cops (I don’t carry a phone on Shabbat). My kids have never seen me this angry and uncontrolled. To them, the Sieg Heil is something that only happens in the black-and-white movies played back home on Holocaust Remembrance Day. Until I reacted, the salute hadn’t even registered with them.

Early in the novel, Shmuel Yosef is cursed when visiting the town of Grimma, where he has gone to help a widow with her late husband’s bookcollection:

A man passed me in the street and growled, “Russ!” As you know, I am a Galitzianer and not a Russian. Although Russ is not a dirty word in my book, that lout intended to curse me. Then and there I decided not to spend the summer in Grimma after all. I’d be better off in Berlin, a big city that is used to Jews.

Berlin is again used to its Jews. The phone rings in my study. There’s a compassionate voice on the line owned by a Detective Sievers, who works in the hate-crime unit at the Berlin police department. “Hallo, Herr Secunda. We’ve received the report you filled out online about that antisemitic incident and we’d like you to come down to the station in Tempelhof. . . . No, it really can’t be done over the phone.”

I wonder what my grandparents would think about being summoned to a German police station. I also recall Shmuel Yosef’s regular appearances at the Tempelhof police headquarters, to check in with the draft authorities:

One day, I traveled to Tempelhof with the other cases. Some were disfigured, some covered with sores, some were blind, some lame, and others were afflicted with every illness imaginable. I looked at all those broken people who brought their brokenness to the war officials. I thought, I may have kept out of the war so far, but from now on, even the accursed Jews won’t be spared.

To This Day, a great novel of the Great War, contains some of the most unforgettable images of injured veterans in world literature—a Hebrew echo of the disquieting, antiwar paintings made by the brilliant caricaturist George Grosz (one such painting is reproduced on the front cover of the English translation of To This Day). There are no longer such awful sights to be seen at the Tempelhof Police Station, though in Berlin one once again meets those who have been broken by a

European war.

At the police station, Detective Sievers apologizes for Berlin’s antisemitism problem, which he acknowledges is considerable (“Let’s just say that I am a busy man”). As he interviews me, he explains the difference between the crime of antisemitic hate speech, which requires intent, and the unconstitutional symbol of the Hitler salute, which is outlawed even if it is performed mindlessly. As a talmudist, I am fascinated by the legal distinction, and as a visitor, I am encouraged by the seriousness with which the police treat a nonphysical assault.

Yet my family and I are still shaken. The assault hovers over the upcoming holiday like a stubborn rain cloud. And although I cannot figure out how to get the materials needed to make a sukkah, and my apartment’s proximity to an embassy means that there may be security issues in erecting one, I know that the only thing that will boost our spirits is to find a way to build the holiday booth.

Salvation comes in the form of a tiny pop-up sukkah, lent by a kind local rabbi. It is all of one square meter, far too small to seat the family, and is too flimsy to last more than a few hours. But we manage to put it up for a holiday party we host in the garden. Friends arrive for pumpkin soup, beer, and German pretzels, some of them ducking into the sukkah to shake our lulav and etrog. Of course, a sukkah is a temporary structure, and this one is quickly dismantled and stored on my porch. Within a few days, my family returns to Israel, the bright foliage disappears, and I struggle to find direction in my research as Berlin’s gray winter descends.

Critics have noted that To This Day tells at least three stories of wandering and return. The first is that of Shmuel Yosef himself. Another is of his landlady’s son, who is feared dead in battle yet turns up, shell shocked, in a convalescence home for soldiers, from where he is accidentally returned—by Shmuel Yosef—to his home on Fasanenstrasse. Finally, there is the widow from Grimma’s library. Her late husband’s books had seemed like they would disappear into oblivion, but on the last page of the novel it is abruptly revealed that they are being shipped to Shmuel Yosef in his new home in Jerusalem.

Narrative endings should satisfy readers, yet these conclusions have an unsettling effect. The landlady’s son is alive but not well. And when this “golem” is restored to his childhood room, he displaces Shmuel Yosef, who is made homeless again. The library is merely scheduled to arrive in Jerusalem, but we are not told if it ever does. And the inexplicable abruptness of Shmuel Yosef’s return to Zion, and his laconic explanation—“since I could not find a room abroad I was forced to return to the Land of Israel”—makes one wonder. Has Shmuel Yosef reached his destination, or is this just another stop along the way?

It is perhaps relevant to note that the author of To This Day—that is, the historical Shmuel Yosef Agnon—did not, in fact, return to Palestine from Germany during or soon after the war. He married and had children. The letters Agnon wrote during his time in Germany occasionally remember Zion, but mostly, they record the efforts of a man to live a civilized life in a decent apartment. In one, Agnon complains of a flat on Krumme Street in Charlottenburg with a whining flourish that could have been plucked from the pages of To This Day. “The room is so gloomy even Satan’s grandmother could not weave in its darkness a noose for the most wretched felon!” Tellingly, a letter from April 1917 sent to Agnon’s patron, Salman Schocken, is signed “the eternal wanderer.” With his decision to write To This Day late in his career, one wonders whether despite his decades in the Promised Land, Agnon still saw himself as a wandering Jew.

Indeed, the novel contains some of the most cosmopolitan reveries and non-Zionist musings ever penned by Agnon, who is sometimes misunderstood as a parochial Zionist, though he had a hand in this. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he described himself as a member of “the Tribe of Levi; my forebears and I are of the minstrels that were in the Temple, and there is a tradition in my father’s family that we are of the lineage of the Prophet Samuel, whose name I bear.” Knowing Agnon’s later Orthodox identity, it is also remarkable that Shmuel Yosef’s love interests in To This Day are almost all non-Jewish.

And yet Agnon is not some kind of smug diasporist. His wandering narrators are often wracked by guilt, bemoaning their poor decisions. On the fast of Tisha b’Av, Shmuel Yosef is accosted in front of the Fasanenstrasse Synagogue for his relationship with a non-Jewish actress. Elsewhere, he reflects on his inexplicable decision to leave Palestine and come to Berlin: “A Jew dwells in the Land of Israel and lacks nothing; the Evil Inclination comes and tempts him to descend to the Diaspora.” In another novel, a narrator writes autobiographically:

[It is] the habit of young men to run away from what is right for them and to run after what is not right for them. But it is not only young men who do this; every man does so, and even the inanimate. Perhaps you will say: But is it possible for the inanimate to run away—it is fixed in place! But I tell you: I myself have seen it, for when I was a lad in the Study Hall, the Study Hall ran away from me, and when I went up to the Land of Israel, the Land ran away from me.

The word “place”—maqom, in Hebrew—is a key term for Agnon in his reflections about Jews, their wanderings, their complex relationship with God—who is also called maqom (Presence)—and their longing for the Promised Land.

In the short story “Tehilla,” a narrator encounters in Jerusalem “the new immigrants which the Presence (ha-maqom)brought to their place (meqomam) and yet had still not found their place (meqomam).” This, ultimately, is what To This Day is about too: “Our story is of a man who has neither house nor room, having left the place he had and let go of the place he found. And so, he went from place to place in search of a place.”

As the year progresses, my roving intensifies. In my writing, I jump from chapter to chapter, intimidated by the outlandish size of my research project, which has the working title “Sea of Babylon.” The Talmud is a great bewildering sea, encompassing within its distant shores long chains of tradition, infamously winding discussions, and no steady surface in sight.

I am always on the move, among meetings, between thoughts, and frequently on flights to and from Israel. On weekends when I stay in Berlin, I find myself pounding the pavement, in awe of the city’s urbane multiplicity while still missing my provincial Israeli suburb. As winter melts into spring and I can again sit on my balcony, I free up some space by finally returning the portable sukkah. With just a few months left in Berlin and contemplating a resumption of my transatlantic life, I start to come to terms with the fact that I will remain—at least partially, at least for now—a wanderer in the diaspora.

Meanwhile, I continue to run into Shmuel Yosef on the streets of Berlin. It turns out that my local kosher store is a few steps from Dahlmannstrasse, where the narrator chances upon a room he hopes will be amenable (alas, it’s a mess). One of my regular coffee haunts is close to the former site of the Fasanenstrasse Synagogue. And coming back one Friday night, I realize that I have forgotten the key to my building. I panic and then discover that luckily—and curiously—someone had left the door slightly ajar. Gratefully sprawled on my couch later that evening, I pick up another Agnon novel, A Guest for the Night. Within minutes, I come across the following lines:

I returned to my hotel and found it locked. I was sorry that I had not taken a key, as I had promised the hoteliers that I would not trouble them much and now I would need to rouse them from their sleep. . . . I stretched out my hand and tried the door, like one who stretches out their hand and does not expect to find it open. As soon as I touched it, it opens.

Ultimately, no matter how much we are forced to wander, we all need some place to stand. Reading and rereading To This Day in Berlin, I begin to wonder, almost desperately, what exactly Agnon is proposing.

The solution, I think, is to pay attention to Shmuel Yosef’s narrative voice rather than the real estate he occupies. For he turns out to be a remarkably grounded narrator who perceives the rushing, modern world from the perch of a rich, old, and impressively erudite language. It is trite (and almost insufferable) to point out that Agnon is diminished, indeed fundamentally different, when read in even the best translations. And yet, the fact remains that only in Hebrew does Agnon turn the trick of seeing the exciting and disorienting sites of Berlin through the old, enduring eyes of Hebrew learning.

On almost every line, Agnon’s Hebrew reaches back to, retrieves, and refashions the language of the Bible (“Man is as a tree of the field”—ha-adam eitz ha-sadeh), rabbinic literature (“One war draws another war”—milhamah goreret milhamah), kabbalistic texts (“a man like me, who knows how to contract—le-tzamtzem—himself”), medieval Jewish philosophy (“is it possible for the inanimate—domem—to run away?”), and more. The strange people Shmuel Yosef meets, the unusual experiences he has, and the wandering, wondering thoughts that he thinks are all filtered through that distinct Agnonian argot, in which the peculiar vocabulary and distinct phrases of the classic Jewish bookshelf inform and form a way of being in the world.

This register is an obvious choice for telling tales of the Jewish Old World. It is also well suited for chronicling the Zionist undertakings of early-twentieth-century Palestine, which included, of course, the revival of Hebrew. But the use of Agnon’s enchanted Hebrew to describe the tumultuous world of wartime Berlin, its crowded streets and speeding streetcars, wounded soldiers and weeping widows, rowdy taverns, and avant-garde cabarets, is a revelation—one in which a life can be lived.

Suggested Reading

At Professor Bachlam’s

A lost chapter from Agnon's final, classic novel Shira, translated here for the first time.

On Agnonizing in English

For the Hebrew reader, S. Y. Agnon is not merely canonical, he stands almost outside of time.

Wandering Jews

Jews have been travelers since God told Abraham to get up and go. How deeply has this constant motion been imprinted on the Jewish psyche?

Temporary Measures: Sukkah City

The reimagining of an ancient architectural ritual.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In