Jacob in the Bosom of Abraham

The book of Jubilees, which very few Jews have read over the past two thousand years, is a gonzo retelling of Genesis and parts of Exodus. Composed by an anonymous author (or possibly authors) during the Second Temple period, before the Maccabean revolt, it purports to be the words of an angel who spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai. And it reads like the world’s first fan fiction.

The book is full of time-jumps and wild narrative connections. In Jubilees’s whimsical imagination, Noah founds the holiday of Shavuot, Moses’s staff first belonged to Adam, and the king of Nineveh is really Pharaoh in disguise! Hundreds of years before rabbis sought to connect diverse storylines in midrash, Jubilees’s narrative presents a whopper of a “what if?” But, like the later midrash, it also speaks to the deep anxieties and poignant wishes of the Bible’s early readers.

In the Torah, Abraham passes away in ripe old age, and is buried by his reunited sons Isaac and Ishmael. After the patriarch’s death, readers follow the storyline of Isaac, whose dueling sons Jacob and Esau haggle, trick, and (in the form of an angelic stand-in) wrestle over the birthright that had passed from Abraham to Isaac. But in Jubilees, Abraham himself not only lives long enough to meet his grandson Jacob, he blesses him twice and dies in his arms.

Abraham’s first benediction affirms that Jacob is his true heir and successor:

May the Lord give you righteous seed and may He sanctify some of your sons in the midst of all the earth. May the nations serve you, and all the nations bow down before your seed… May He cleanse you from all sin and defilement.

The scene of the second blessing, on Abraham’s deathbed, is heartbreaking. In the translation of the Jewish Annotated Apocrypha it reads:

And both of them lay down together on one bed. And Jacob slept on the bosom of Abraham, his father’s father. And he kissed him seven [times], and his compassionate heart rejoiced over him, and he blessed him with all his heart, and he said “God Most High [is] the God of all, and Creator of all who brought me out from Ur of the Chaldees so that he might give me this land to inherit it forever.”

As his young grandson “lay on his bosom,” Abraham ensures that Jacob and his descendants will inherit the covenant:

And he blessed Jacob, saying, “My son [is] one in whom I rejoice with all my heart and all my emotion. And may Your favor and Your mercy rest upon him and upon his seed always. And do not forsake him and neglect him henceforth and for the eternal days. And may Your eyes be upon him and upon his seed so that You might protect him and bless him and sanctify him for a people who belong to your heritage. And bless him with all of your blessings henceforth and for all of the eternal days. And renew Your Covenant and Your mercy with him and with his seed with all of Your will in all of the earth’s generations.”

Abraham then places two of Jacob’s fingers on his eyes, blesses God one last time, and is “gathered to his fathers.”

Jubilees tells us that little Jacob awoke, “and, behold, Abraham was cold as ice, and he said, ‘O father, father!’ and none spoke. And he knew that he was dead.” Jacob, Isaac, Ishmael, and the sons of Keturah then mourn Abraham for forty days. Esau is noticeably absent.

The Torah itself, of course, has no such scene between Abraham and Jacob because the two never meet. But an unyielding canon can often be unsatisfying—both to readers and to its characters. Moses does not make it into the Promised Land. David commits adultery and murder, bringing punishment to himself and his kingdom. We never know how the rest of Esther and Ahasuerus’s marriage played out. Jacob, no doubt, would have loved to meet his grandfather, and Jacob’s descendants, the Children of Israel, would have loved it if his claim to the birthright was less complicated.

The rabbis felt the same urge as Jubilees to fill in the blanks, redeem immoral acts, and edit plotlines. David never sinned with Bathsheba (certain legal loopholes made his actions permissible). The royal couple of Shushan produced a son, Cyrus, who allowed the Jews to rebuild the Temple, and so on. (Moses, alas, still never makes it into Israel.) Rabbinic midrash also implies that Abraham and Jacob met, albeit offstage. The Talmud in Bava Batra quotes an earlier tradition that the red soup that Jacob traded for Esau’s birthright was lentil soup, which Jacob cooked to comfort Isaac as he mourned Abraham. And yet the rabbis do not play out the narrative conceit; they do not show us Jacob at his grandfather’s deathbed while his twin brother was out in the field.

But in Jubilees, Jacob got to hug his Zayde.

Suggested Reading

All-American Esther

Stuart Halpern’s anthology Esther in America tells the story of the surprising uses to which the story of Purim has been put in American history.

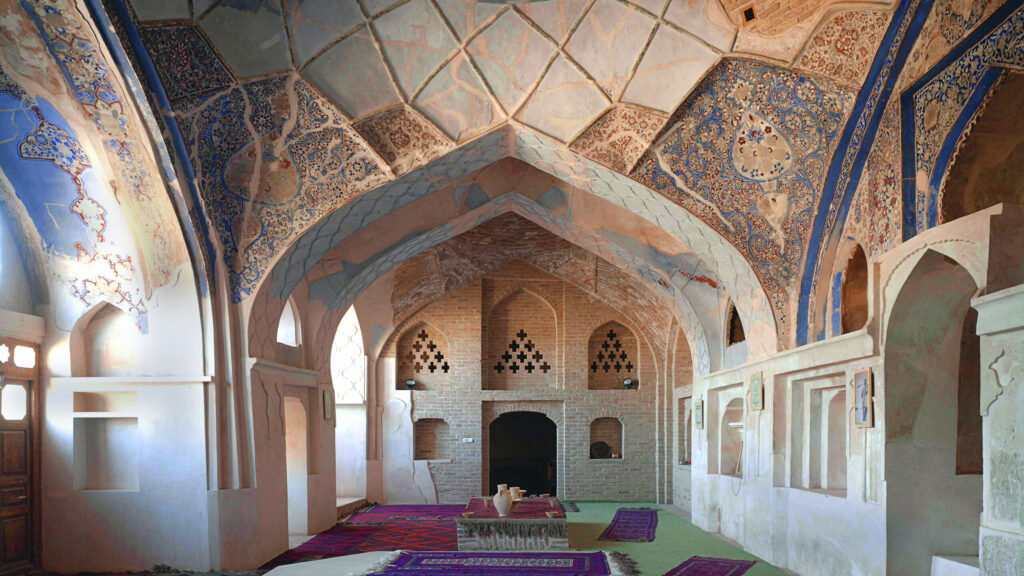

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Inside-Out

The boundaries between the biblical canon and the Apocrypha have seemed firm for a long time. But what if the walls aren’t that solid?

Haman, Builder of Towers, Brother of Abraham?

A new book raises the possibility that interpretive motifs from within both Jewish and Islamic traditions might have led to the uniquely Islamic tradition that Abraham and Haman were brothers.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In