All-American Esther

I always loved Purim and not simply because of the racket we were permitted to make in services (on all other nights, we were shushed) every time the cantor chanted Haman’s name. Nor was it the synagogue carnival that held the holiday’s appeal (when I asked my siblings what they remember of these festivities, two of my sisters immediately said, “Dead goldfish in plastic bags”). For me, it was the story itself: the sumptuous setting of the Persian Empire, the suspenseful plot, the timely reversals, and the happy ending. Most intriguing of all, thanks to the creative reading of the rabbis, the story featured the idea of a grown woman dancing without her clothes. It was the late 1960s, and the fact that Vashti boldly refused to do it made me appreciate the story all the more.

My fondness for the story never faded, but before reading Esther in America, a new anthology edited by Stuart Halpern and out just in time for Purim, I had no idea just how many American historical figures shared my enthusiasm. Composed of 28 short but still substantive essays by writers, rabbis, and scholars, Esther in America is an exegetical page-turner. There is real excitement in learning where the story has turned up and who has used it to do what.

In early America, crypto-Jews living in New Spain under the Inquisition prayed for Saint Esther’s intercession. They figured that she, having kept her own Jewish identity secret in King Achashverosh’s court, would understand their predicament. Esther also appears in the etiquette guide of New England’s Cotton Mather. In the 1690s, the New England Puritan urged women to behave like the beautiful and brainy queen, obedient and independent, even furtively assertive (particularly, Mather hoped, when their husbands strayed from godliness and prayer). Three-quarters of a century later, colonists petitioning King George feared that he, their Achashverosh, had fallen under the spell of his Hamanite ministers, intent on depriving them of their liberty. In antebellum America, abolitionists and feminists, including the Grimké sisters, Frances Harper, and Sojourner Truth, emulated and evoked both Vashti and Esther. When a mob of men tried to disrupt the Women’s Rights Convention in New York City in 1853, Truth stood up to them, speaking of the time, in Persia, when a woman could be killed for approaching the king unbidden. “But Queen Esther come forth, for she was oppressed, and felt there was a great wrong, and she said I will die or I will bring my complaint before the king.”

Abolitionist ministers ensured that Mordechai was not forgotten. They imagined themselves following his example as they appealed to their Esther, Abraham Lincoln, who in the early years of the Civil War they believed moved too slowly to abolish slavery. The superintendent of New York City’s first Jewish orphanage, which opened in 1863, also took inspiration from Mordechai, Esther’s foster father. Toward the end of the century, new immigrants found solace in the story of trials and ultimate triumph of all the Jews in Persia, while Jewish revivalists found allies in their fight against antisemitism on the one hand and assimilation on the other. In the years since, artists, filmmakers, authors of children’s books, historians studying White House intrigue (and politics more generally, especially at the precarious moment of Israel’s founding) all made use of the stories characters, plot, and themes.

When it comes to the story’s appeal, there is nothing exceptional about America. Still, some things stand out. One is the paucity of conflict among interpreters. I come to Esther in America from a deep dive into the interpretation of Genesis 22, the story of Abraham’s binding of Isaac known as the Akedah. Enter that ever-expanding universe at virtually any point, and you find yourself in a brawl. There’s name-calling, book burning, even accusations of child abuse. It is not that the contributors to this volume are not angry. They are: at the Inquisition, slavery, the subordination of women, sexual harassment, racism, antisemitism, Hitler and the Holocaust, even political correctness. They simply are not angry at one another, at least not here.

It is not that there is nothing to argue about. For starters, neither the story’s narrator nor any of its characters mention God, which might mean he is missing, leaving human beings to fend for themselves, or might mean, as we learned in Hebrew school, he is everywhere, pulling all the strings. If he is everywhere, he does not seem to mind that his people do not appear to be observing his commandments (though Mordechai may have been thinking of the second when he refuses to bow down to Haman). Nor does he mind that Esther saves the day by hooking up with a man who is not Jewish, the ex-husband of the woman, also not Jewish, who started all the (good) trouble. There is much more, all culminating in the eye-popping collective punishment, which includes the execution of Haman’s 10 sons at the end.

There are nearly as many different ways of understanding the story as there are rabbis, lay readers, and scholars. Comedy is one of them. The characters are caricatures, the setting over the top, the plot fantastical. The closeted Jewish orphan becomes the queen of Persia. Her father, an iconoclastic enemy of the king’s main minister, foils a plot against the king. Then the queen foils a plot against the Jews. Haman gets his comeuppance, hung on the scaffold he built for Mordechai. The numbers are a clue: 127 provinces, a 180-day feast, 10 banquets, a scaffold 50 cubits high, and especially 75,000 dead Persians. With all due sympathy and respect for the many readers who have rent their garments over the thought of such wildly disproportionate punishment for a foiled conspiracy, those numbers suggest that we should enjoy the drama and the bawdy humor but avoid taking the story too seriously or only seriously.

The comic elements of the story, together with the frivolity of the Purim holiday, may well contribute to the relative peace among interpreters. They also make it all the more striking that, on the evidence of Esther in America, there has been so little humor in the American response to the story, not even in the children’s books, the movies, or the arts.

Dara Horn begins her essay by noting that Esther is supposed to be a funny story. “Despite its near-miss genocide—let’s be real, because of its near-miss genocide—it manages to be the most lighthearted and entertaining story in the entire Hebrew Bible.” And to Americans, it is also the most familiar. Not just the sex and the booze, the nice Jewish girl, and the cartoon villain, but also the overwhelming sense of comfort: “Our lives here, in the land of the free, are supposed to be exactly this: a delightfully frivolous, elaborately decisive refutation of the dour history of diaspora Jewish life.”

But the story is not just that, and for Horn, the first hint is the name change. Why, she asks, if life was so good for Jews in Persia before Haman’s edict, did Mordechai and Esther (born Hadassah) give up their Hebrew names? That question gets her thinking about all the American Jews who in the first half of the last century changed their names. It also gets her thinking about another “funny” story, the common explanation for all those American Jewish name changes: It was said that immigration agents changed people’s names at Ellis Island. Horn thought everyone knew that the Ellis Island story is not true, but when she mentioned the “myth” in passing in a lecture, she was nearly chased off the stage. Her contribution to this volume is bittersweet and wise in its appreciation of the way we often substitute wildly creative and also palatable fictions for painful experiences. We tell an Ellis Island fairy tale instead of remembering the prejudice, discrimination, and exclusion that led so many people to try to disguise their religion and ethnicity. We tell of Esther’s triumph instead of exile and precarious lives as a minority community in Persia. “Other ancient Jewish stories, like those of Passover and Hanukka, tell a similar story of a triumph over evil, but those stories do not bury their trauma under laughter and joy.”

Liel Leibovitz also begins his chapter humorously, recalling how when he was 10 he dressed up for Purim as Rambo, shoe polish under his eyes, toy gun in his hand. The fun ended—the taste of his poppy-seed pastry spoiled—when he realized that the Megillah ends with the “joyous massacre” of Persians. In his righteous youthful distress, he found lots of company. As the decades passed, he returned to the text and what he found was a particular kind of retribution for a particular kind of enemy and crime: not revenge for the sake of revenge, not for spoils, not to eliminate a race or class, but a terrible swift sword against people intent upon injustice, oppression, and murder. It is a reading that transforms “a gritty tale of revenge” into “a benevolent if bloody expression of morality.”

Leibovitz’s Hamans today are thought police, speech codes, tribalism, social justice warriors, and “Cancel Culture.” He is an agile writer, and I can imagine him going after them with parody and wit. His targets give us tzuris but also a lot to mock. Purim is a good moment for mockery. Instead, he again grabbed a gun.

What Esther in America suggests to me is that great as the temptation is to make light of the story, other opportunities it provides are too precious to pass up. One is the opportunity to write about the experience of Jews as a small minority, which has been the experience for most Jews for most of Jewish history and remains the experience of roughly half of the Jews in the world today.

Another is the experience of Jews in situations where God, whether everywhere or nowhere, is not weighing in. I am not thinking about religious observance. There he left instructions. I am thinking about those dimensions of our lives that lie beyond specific commands and laws. Esther in America allows us to think about community responsibility and personal responsibility, leadership and followership, speaking out and going along, direct action and subterfuge, injustice and reparations, self-care and self-endangerment, vigilance in the face of tyranny, and hope and faith in the dark.

I like to laugh as much as anyone, and I will, yet again, when I reread Esther this year. But I cannot ask for more from a Bible story or from the congregation of gifted readers and writers Halpern has brought together to shed light on its long and protean life.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

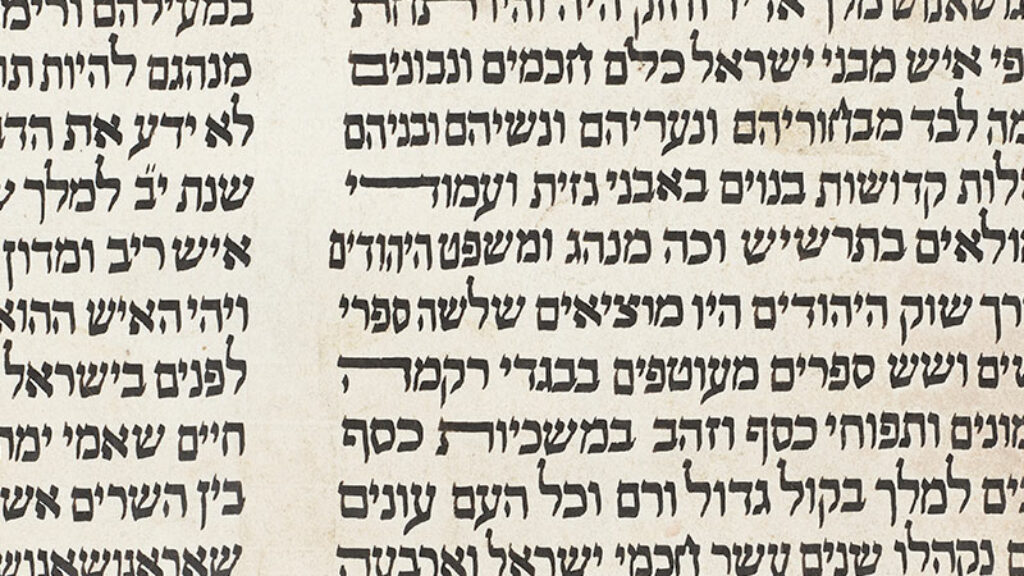

Empty Torah Cases and “Little Purims”

There are more than a hundred known examples of Little Purims commemorating miraculous deliverances of Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Hidden Faces and Dark Corners: Megillat Esther and Measure for Measure

What happens when the hidden is revealed? Reading Megillat Esther alongside one of Shakespeare’s “problem plays” shows that question to be at the heart of Purim’s paradox.

Suspecting Esther

For Seymour Epstein, the Megillah depicts the cycle of passivity and overreaction that is endemic to the diaspora.

Haman, Builder of Towers, Brother of Abraham?

A new book raises the possibility that interpretive motifs from within both Jewish and Islamic traditions might have led to the uniquely Islamic tradition that Abraham and Haman were brothers.

Marcus Moseley

Jan 6 was a Jacqerie.