Letters, Winter 2023

From the Editor:

As we were closing this issue, I was, like you, talking with friends about the recent Israeli election—the usual conversations, half potted punditry (at least on my part), half worried banter. When I spoke with JRB editorial board member Hillel Halkin, he surprised, even shocked me. It wasn’t his erudite eloquence that surprised me—Hillel is, after all, one of our great essayists, and the author of brilliant books on, among other things, the necessity of aliyah, the legend (reality?) of the lost tribes, and biographies of Yehuda Halevi and Ze’ev Jabotinsky, not to speak of his neo-Platonic novel and incomparable translations of everyone from Agnon to A.B. Yehoshua. It wasn’t even his anger. It was the way in which he challenged me to rethink not only the current Israeli government but something much more fundamental.

By now you will have read and argued over many critiques and defenses of the Netanyahu coalition. But Hillel does not write op-ed pieces, and we do not publish them. He has done something much harder, more important, and more personal. He has returned to the fundamental goal of Zionism—at least of secular Zionism—the goal of turning Jews into a normal people. And he asks whether the Jewish state, the state to which he has, in many ways, committed his life, has failed to achieve that goal—and, in Halkin’s metaphor, fallen off a cliff.

What provoked me most about Hillel’s argument was not his criticism of the current Israeli government, certainly not its more disreputable members. Nor was it his political analysis, which turns on contingencies of demography, culture, and politics of which no one can be sure. It was rather his certainty that to become a normal people, Jews must give up on being the chosen people. That is, we must give up not merely the Otzma Yehudit party’s notion of choseness or (lehavdil) Yehuda Halevi’s but also on the rationalist versions of Maimonides or Mendelssohn, because inevitably any notion of being chosen by God will eventually lead back to the crudest version—and take Israel over a political cliff.

There is much more to Halkin’s essay and much more to say in response to it (and we will publish some of those responses), not to speak of all the other great pieces in this issue, but I’ll close by reiterating something about the Jewish Review of Books: We are a forum, not a platform; a conversation, not a polemic.

Abraham Socher

Editor, Jewish Review of Books

Harsh Criticism

As a physician, when I scanned the contents of the Fall 2022 issue of the JRB, I was drawn to “No Balm” by Shai Secunda, a review of Jason Sion Mokhtarian’s book, Medicine in the Talmud: Natural and Supernatural Therapies between Magic and Science (Fall 2022). Secunda details several deficiencies in the material and flaws in the analysis. But the over-the-top attack on Mokhtarian’s scholarship— “sloppy,” “obtuse,” and “lazy” in a single sentence—and the vituperative tone give me pause about the overall validity of the critique. Medical research manuscripts are generally reviewed by at least two referees. Can a single reviewer be so confident in his or her assessment? One is left thinking that Secunda had written the penultimate paragraph of the review and was waiting for an opportunity to unleash it in print. It brought to mind the violent review by Haym Soloveitchik of Talya Fishman’s book Becoming the People of the Talmud: Oral Torah as Written Tradition in Medieval Jewish Cultures (Winter 2013). Scholarship should be held accountable to the highest standards. But the Jewish Review of Books would be wise to remember that even if derekh eretz does not precede Torah, the two should at least go hand in hand.

Chaim Trachtman

New Rochelle, NY

Shai Secunda responds:

What Dr. Trachtman knows from medicine is also true in the humanities, including academic Jewish studies. Books published in university presses are assessed and approved by at least two reviewers and then subsequently reviewed by an editorial board. Yet the process only works when readers, press editors, and boards alike are willing to engage, when necessary, in the unpleasant task of rejecting a submission. Unfortunately, the ecosystem of American academic book publishing has become one in which positivity and pleasantness are prized above all, and criticism and rejections are vanishingly rare.

After reading Medicine in the Talmud and confirming my critical impressions of the book with a number of colleagues, I realized that a critical review was in order. I did not relish this task and do not intend to make a habit of it. Nevertheless, for the health of the field, I maintain that it was necessary. Collegiality is an important value. But expertise, rigor, and critical discernment are the pillars on which intellectual life rests.

Mussar and Bitania

David E. Fishman’s portrayal of life of the students in the mussar yeshiva of Novaredok, in his article “Chaim Grade: Portrait of the Artist as a Bareheaded Rosh Yeshiva” (Fall 2022), raised, in my mind, some possible similarities with an effort by a group of ideological Zionists to uproot their own personal egotistical drives. I have in mind the short-lived kibbutz of Bitania near the Sea of Galilee, created in the 1920s and numbering some fifty members, mostly from Galicia.

Fishman describes the atmosphere and teachings at Novaredok as aiming “to defeat the sinful urges that control human behavior: lust, greed, pride, laziness, anger, and so forth.” This took place in “a state of extreme emotional excitement.” It also included “impassioned motivational sermons on self-transformation” and “introspection while in seclusion,” as well as meetings to examine each other’s progress. Relations between students were intimate and intense: “they knew virtually everything about each other and constantly judged each other.”

Bitania belonged to the Marxist Hashomer Hatza’ir, but included a mixture of ideas derived from Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Martin Buber, as well as some of the Wandervogel movement, with its romantic worship of nature and its disdain for bourgeois values. As recalled by David Horowitz, one of its early members: “Perhaps we shall be the first torrent of youth to remain young forever . . . to live in simplicity, beauty and truth. Perhaps our new edda will be the nucleus of a new culture of new relationships between humans leading communal lives.” Bitania was led by Meir Yaari, the future leader of the Marxist Mapam political movement. A man of extraordinary intellect, personal magnetism, and suggestive power, he is portrayed as the unchallenged guru of the group.

Horowitz likened Bitania to a “monastic order,” a “religious sect” without God. Candidates passed a trial period, a kind of novitiate, that included a ritual of confessions in public. After spending ten to fourteen hours a day working hard in the fields, real life began in the evening. Members engaged in the sicha, literally “conversation,” but in reality, a prolonged session of monologues and near-hysteric public confessions where members bared their innermost secrets, sexual anxieties and dreams, doubts, yearnings, and perplexities. A catharsis was achieved by this obsessive sharing. “We confessed to each other,” writes Horowitz, and they called it their “night of atonement.” The land they tilled was their bride; they were its “bridegroom who abandons himself in his bride’s bosom.” Speakers sometimes fainted from excitement at the rostrum. “There were times when I feared that collective madness would seize this lonely congregation,” shares Horowitz.

Some of its members later assumed important political and economic posts when Israel came into being. I wonder how many of the mussar yeshiva members equally assumed important rabbinical posts in the haredi community, such as Avrohom Karelitz, better known as the Chazon Ish.

Mordecai Paldiel

New York, NY

Abraham’s Test

Roslyn Weiss’s reading in her article “‘The One You Love’? A Case of Divine Disappointment” (Fall 2022) that God was testing whether Abraham loved Isaac as much as God did, makes much more sense than the idea that God was testing Abraham’s faith. I love the fact that, after generations of other readings, Dr. Weiss had the imagination and courage to develop a new understanding.

Mike Abram

via email

Suggested Reading

God and Idolatry

Saving God may look Maimonidean on the surface, but Rambam would never agree with Johnston's basic conclusions.

WeShtick

Neumann’s kibbutz identity was part of his personal brand to such an extent that when puzzled onlookers spotted him walking barefoot on a Manhattan street, raising questions about his mental health, one of his publicists explained, “He is a kibbutznik.”

Prospects for American Judaism

A new book traces the path of American Jews from participation to affiliation.

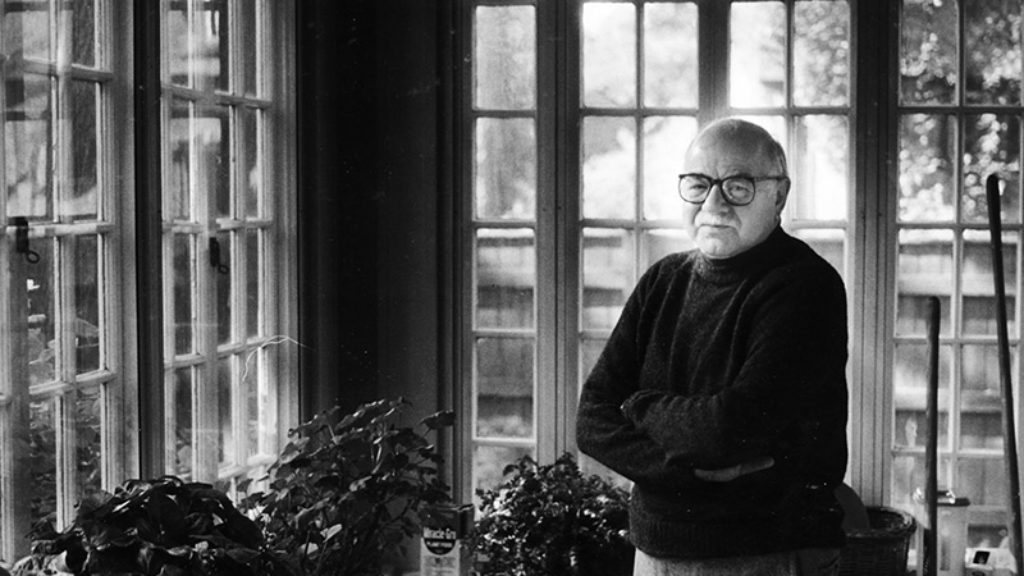

Daniel Bell (1919-2011)

In memoriam.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In