Of Were-Owls and Wandering Jews

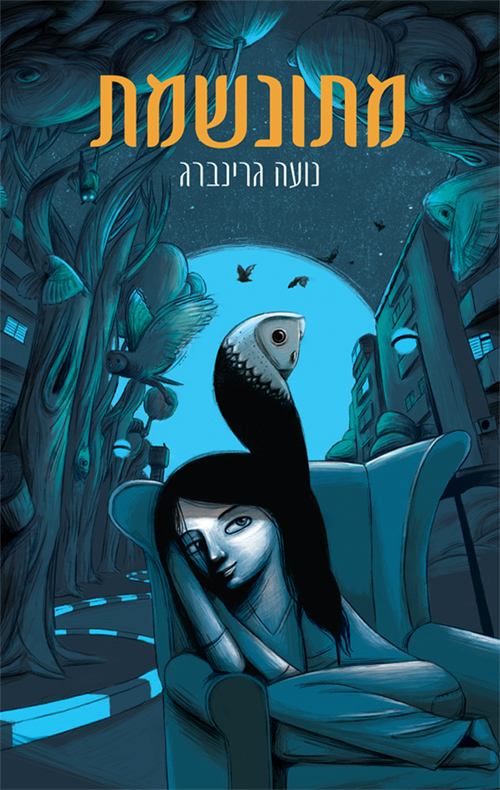

There were two Jewish shape-shifters in my Faerie and Zion reading this month. The first is the protagonist of Metunshemet (Owled), an Israeli novel for younger readers. Noga is a sixth grader in Kfar Sava. But she also has a second, secret identity: each night she turns into an owl. She has an owl friend named Vermeer and some acquaintances among the neighborhood fruit bats, but finds all of her nocturnal relationships far less challenging than the ones with her parents, her younger brother, and the other kids at school.

The notion of a were-owl may seem peculiar, but it has a history. Owls, after all, are unsettling creatures. Parsing the names of the unkosher birds in Leviticus, Rashi explains which Hebrew terms correspond to the French hibou and chouette (owls both): “They cry out at night and have the facial structure of a man”—that is, their eyes are in front, like humans, not on the sides like most birds. In some medieval Christian bestiaries, owls represent Jews, since both love darkness and inhabit ruins. During the same period, the Sefer hasidim warned Jews about strias—the term derives from the Latin for “owl”—women who drink human blood and can fly when they unloose their hair.

Not that Noa Greenberg had medieval tomes and commentaries on her mind. Metunshemet is a tender dramatization through fantasy of the isolation, secrecy, and conflicted desire for independence and reassurance that are the lot of many a tween girl. Now that I think about it, it joins a couple of other imaginative owl books for young readers by authors of Jewish background: Kathryn Lasky’s Guardians of Ga’Hoole series, and Arnold Lobel’s melancholy classic Owl at Home.

On the adult side, Peter Beagle’s zesty parable, which I just picked up in a 1974 chapbook edition, begins: “Lila Braun had been living with Farrell for three weeks before he found out she was a werewolf.” As you might expect, the relationship doesn’t last, but it’s not because of Lila’s night feeding, or a silver bullet, or even what happens when she goes into heat. No, the reason is somewhat more common to American Jewish fiction of the 1970s:

“Just a minute,” he said. He covered the receiver with his palm. “It’s for you,” he said to the wolf. “It’s your mother.”

The wolf made a pitiful sound, almost inaudible, and scuffed at the floor.

Lila the Werewolf isn’t on the level of Beagle’s brilliant, earlier novels A Fine & Private Place and The Last Unicorn, the latter being both a fantasy classic and a profound work of American Jewish post-Holocaust theology, but it has its moments.

I spent much of junior high reading Michael Moorcock’s dozens of sword-and-sorcery yarns, but I’ve only recently gotten to his Byzantium Endures, a monumental if morally ambiguous achievement and very much this-worldly. (I read it along with an excellent critical overview of Moorcock’s career by the poet and biographer Mark Scroggins.) Byzantium Endures shuttles between Kiev, Odessa, and Saint Petersburg during the first two decades of our own 20th century, the rail-crossed, blood-soaked landscape of modern Jewish literature. Yet to an extent more extreme than any character one encounters in the works of Sholem Aleichem, Isaac Babel, I. J. Singer, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, and others who seem (especially Babel) to haunt the novel, Moorcock’s protagonist is a self-hating Jew. In fact, the phrase may not quite be applicable since it is not clear how much of a self Colonel Maxim Pyatnitsky really possesses. Though “Pyat” is utterly convinced that he is of noble Cossack stock, and despite the near-constant stream of anti-Semitic and racist jeremiads delivered by this profoundly unreliable narrator, it is clear to everyone he meets that he is a Jew. Buoyed by his scientific utopianism (as a boy in Kiev he builds a personal flying machine and nearly dies when he crashes, ominously, into the Babi Yar ravine) as well as an extensive cocaine habit, Pyat wanders from one revolutionary and counter-revolutionary faction to the next, largely indifferent to the fate of his victims along the way.

The relationship of this character to his creator’s own Jewish background may be impossible to know—the endlessly inventive and self-parodic Moorcock has more recently turned to a fusion of autobiography and fantasy, which I hope to get to soon—but the book stands as a kind of limiting case for modern Jewish literature, even as it gives off a nihilistic stink. I continue on to the sequel (it is the first of a quartet) with eagerness and trepidation.

This month I also went back to the great Poul Anderson’s 1961 Three Hearts and Three Lions. I hadn’t realized how many fantasy tropes have their roots in that book, from the cosmic battle between Law and Chaos (rather than Good and Evil) that defines Moorcock’s sword-and-sorcery novels, to the notion that fantasy dwarves have Scottish accents. The Jewish connection? Well, not much, but Anderson has his characters follow a quirk of Sussex dialect—the repetition of the plural ending—that resulted in “faeries” being called “Pharisees.” So we are told that “Pharisees canna endure broad daylight” and “Pharisees canna endure the touch o’ cold iron.”

The same quirk comes up in Rudyard Kipling’s 1906 children’s classic Puck of Pook’s Hill, but Kipling was considerably more interested in Jews. The Jungle Book was a much-treasured part of my childhood bookshelf, but no one ever suggested that I read Puck, and now I can see why. Kipling’s fairy spirit introduces a proper English boy and girl to the history of England, conjuring up medieval knights and Roman soldiers to tell their stories. The first chapter, in which Puck recalls how the old pagan deities emigrated and declined, must have influenced Neil Gaiman when he wrote American Gods. Yet the only unsympathetic figure in the whole pageant is the final speaker, a baleful and wild-eyed wandering Jew named Kadmiel.

Kadmiel tells Puck how he was indirectly responsible for the signing of the Magna Carta. Rather than crediting the Jews with the birth of English liberty, however, Kipling’s story has Kadmiel acting out of greed, stealing a treasure coveted by a Jewish rival that might otherwise have filled out King John’s coffers so that he wouldn’t have had to share power with the nobility. Kipling appends his poem, “Song of the Fifth River,” to the tale. It tells how “dark Israel” since time immemorial was granted power to know the mysterious meanderings of the “Secret River of Gold” and its “thousand springs / That comfort the market-place, / Or sap the power of King.” As Kadmiel confirms, “we Jews know how the earth’s gold moves.”

On the one hand, neither Puck nor the English children have a bad word for Kadmiel, and they even suggest that anti-Jewish persecution isn’t quite sporting. But the baleful, suspicious Jew is more alien than any other character in the book, human or fairy. And he is decidedly not of England. Which we are evidently to keep in mind when Kipling has a current-day Jewish interloper named Meyer come through, pheasant hunting on his estate. The river of gold flows on.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Unspun

I reserve the right to chat with you about all of my reading, whether there be dragons or not.

Brave New Golems

As monsters go, golems are pretty boring. Mute, crudely fashioned household servants and protectors, in essence they’re not much different from the brooms in the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” story.

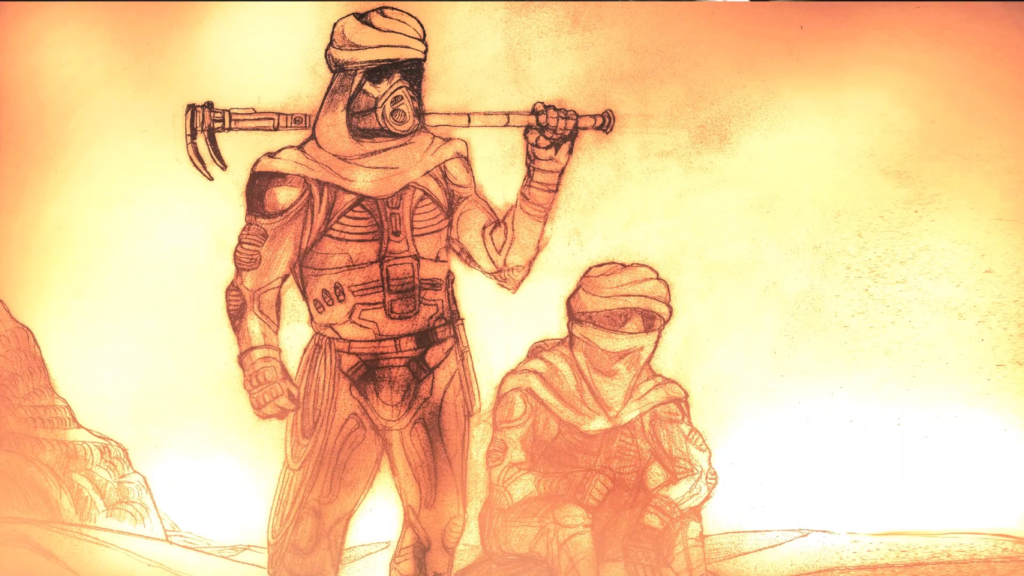

Jews of Dune

In Chapterhouse: Dune, the sixth book in the Dune series and the last Herbert wrote before his death, the Jews show up.

Riding Leviathan: A New Wave of Israeli Genre Fiction

A new batch of Israeli fantasy books may not contain Narnias, but they pound on the wardrobe, rattling the scrolls inside.

Sheldon Posen

I have always wondered if Tolkien’s dwarves—hairy dwellers in darkness, craftsmen builders of underground realms, obsessed with gold, the very opposite of the fair haired, sylvan Elves—were meant (or taken by his readers) to represent Jews.