Raising the Asmonean Banner

We have all felt both the burden and the allure of competing cultures. We’ve perhaps thrilled to the joyous spectacle of sparkling and fantastically colorful Christmas lights on the way to kids’s Hanukkah parties; or maybe we’ve delighted over the deeply moving poetic cantos of the American poet Ezra Pound while turning away from the memory of his notorious wartime broadcasts and essays, for which the 1939 essay, “The Jew: Disease Incarnate,” serves as the most egregious example. And Hanukkah—which commemorates a time the Jewish population was forced to consider not only its political suffering under the yoke of the Seleucid empire, but the implications for their identity as Jews of their participation in Hellenistic culture—is a particularly apt moment for considering the multiple allegiances the Jewish people have historically maintained with other cultures. It’s a theme that echoes throughout different times and places in Jewish history.

One such location was mid-19th-century England. More than 500 years earlier, in 1290, the entire Jewish population had been expelled from the country. They were allowed limited re-entry in 1656 under Cromwell, but the Jews did not gain full civil and political emancipation in England until 1858; until then, they suffered under such official disabilities as an inability to vote or to trade in London and on the stock exchange, exclusion from membership in Parliament, and exclusion from standing for mayor of London.

In 1839, sisters Marion and Celia Moss published their first collection of poetry, Early Efforts: A Volume of Poems, by the Misses Moss, of the Hebrew Nation, Aged 18 and 16. It was one of the first volumes of poetry by Jewish authors in England, and it presents remarkably precocious work that takes the measure of their precarious identities as proud Englishwomen entirely committed to their Jewish heritage.

The boldest of the poems in the Moss sisters’s collection presents a narrative of the infamous York Massacre that had taken place some 650 years earlier. Following a wave of massacres that began at the 1189 coronation of King Richard I, on the Shabbat preceding Passover of 1190 an angry Christian mob drove 150 Jews—the entire Jewish population of York—to take refuge in York Castle. Seeing no hope of escape, they committed mass suicide rather than face the prospect of a choice between slaughter by the mob or forced conversion to Christianity. It was one of the worst moments in Anglo-Jewish history. In their poem, the Moss sisters imagine the rabbi of the York community holding forth to the besieged Jews who had barricaded themselves in the castle, offering comfort:

THERE is an old and stately hall,

Hung round with many a spear and shield,

And sword and buckler on the wall

Won from the foe in tented field:

Yet there no warrior bands are seen,

With martial step and lofty mien;

But men with care, not age, grown white,

Meet in York Castle hall to-night,

And groups of maids and matrons too,

With hair and eyes, whose jetty hue

Belong to Judea’s sunny land,

And mingling with that sorrowing band:

What does the Jew—the wandering race

Of Israel, in such dwelling place?

From persecution’s deadly rage

A refuge in those walls they sought,

The zealots of a barb’rous age,

Ruin upon their tribes had brought.

One of the striking aspects of this poem is that the Moss sisters represent the Jews as embodying England’s most authentic values. What we have in this passage is a description of the English “stately hall” decorated with the proud reminders of English military might, “the sword and buckler on the wall / Won from the foe in tented field.” But in the hall there are no warriors; the image of the brave English of famed and just valor has given way to the blood-thirsty English swarm, and it is the courageous Jews who are sheltering in the halls of the castle—the very symbol of English stability. With their “jetty” (black) hair and eyes, they don’t look like Englishmen—but they embody genuine English fortitude.

Toward the end of the poem, as the moment of mass suicide approaches, the rabbi rallies their courage by invoking the memory of the Maccabees:

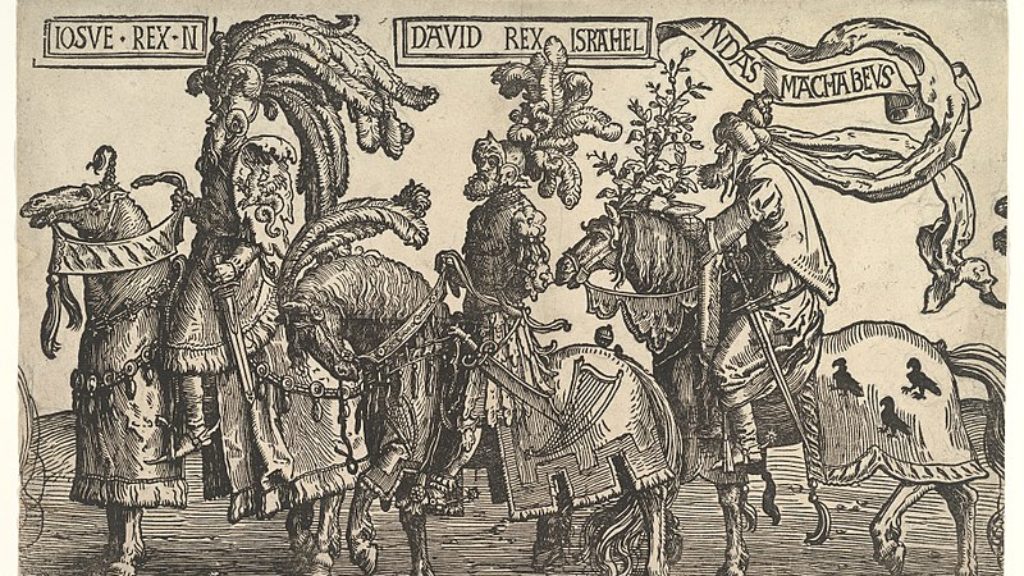

When the Israelites echoed the Maccabees’ cry

As they raised the Asmonean banner on high,

They stayed not to think upon danger or death,

But glorified God with their last fainting breath,

And left in their country’s annals a name

That will ne’er be erased from the records of fame.

Then think on the glorious dead

Of ages long gone by;

Think on the cause for which they bled,

And like them dare to die;

For the laws which our God to his prophet reveal’d,

Yes! Our faith in their truth, with our blood must be seal’d.

Depart! All ye who would be slaves,

Nor dare disturb our latest breath:

Depart! And leave the glorious graves

For those who prefer to apostasy—Death.

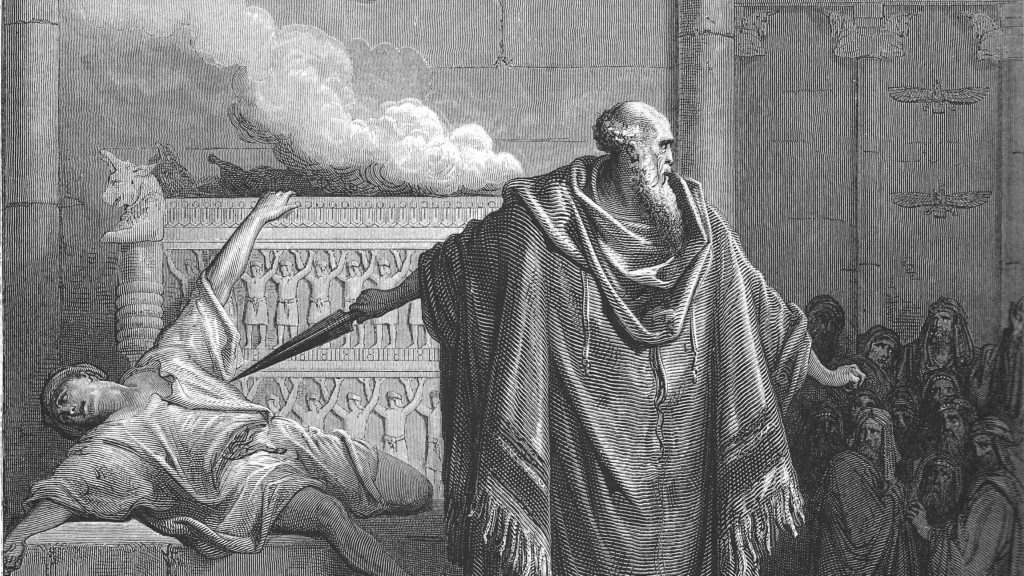

The Maccabees are celebrated for having pushed back against the imposition of Hellenistic values, and especially for forging a rebellion in the name of religious freedom when Antiochus IV proscribed Jewish ritual practice. Their memory is appropriated in this poem to establish the premise of a resolute Jewish identity that can rise to heroism in the face of adversity.

The Jews who die at York Castle will be leaving “in their country’s annals a name / That will ne’er be erased from the records of fame.” And their country is England. This is a rather remarkable turning of the tables, and a splendid irony: this poem about the moment when Jews were victimized as outcasts implicitly becomes a poem about their rightful belonging to a nation whose glorious history they presume to define.

To this ironic reversal we may add one further example of historical context. On the occasion of the defeat of the 1830 Jewish Relief Bill, The Spectator magazine published an indictment of English hypocrisy in their relation to the Jews: “A Jew may be born in England—he may be bred there—he may speak the language, obey the laws, conform to the customs of an Englishman; he may cigar it, drink it, game it, race it, box it, as naturally as the most genuine bit of John Bull extant—and be an alien to all intents and purposes notwithstanding.” For the Moss sisters, though, the Jews are no aliens: they are the proud inheritors of the most authentic understanding of both English and Jewish culture.

Suggested Reading

Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

The exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks on Jewish power and politics is illuminated by the history of Hanukkah.

“When Orchards Burn Their Lamps of Fiery Gold”

Emma Lazarus’s 1882 poem for Rosh Hashanah responded to the crises of her day, foreshadowed “The New Colossus,” and resonates today.

In Memory of Judah Maccabee

That Judah, the great victor of the Hanukkah story, ultimately died fighting the Seleucids is something that surprisingly few Jews know. And were the Maccabees actually underdogs?

EUGENE NADELMAN: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse

"Our tale's debut / Takes place in 1982 / When I, for one, if not exactly / A double of our leading guy / Was like him, bookish, awkward, shy." - Coming of age in iambic tetrameter.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In