The Hebrew Teacher

I’ve lately returned to Israel from my fiftieth Harvard reunion, flush with memories. In my senior year, at the height of the Vietnam era, the university was roiled by tumultuous student protests, a formative experience for many of my classmates. I was living in Dunster House, named for Harvard’s first president, a Hebrew scholar and Puritan clergyman who was ousted in 1654 for his heretical stance on infant baptism.

My mother and father were both Hebrew teachers: She at a shul, he at Brooklyn College. My maternal grandfather, a shoe salesman, was born in 1896 in a Slovakian shtetl and fled to America at age 17 to avoid conscription by the losing side in the First World War. (He never saw his parents again: They were murdered at Auschwitz.) During graduation week in 1969, I took him to see my room, with its wood-burning fireplace and view of the Charles River. It meant climbing three flights of stairs, but each step was pure naches. That same week, members of the Fiftieth Reunion Class of 1919 were housed in Dunster, and, as my grandfather and I made our way downstairs, another old man was slowly walking up and not unreasonably mistook him for a classmate. “How are you?” the fellow shouted convivially. “I’m all right, how about you?” replied Grandpa. As we crossed paths, I glanced at the gentleman’s reunion badge. It was Malcolm Cowley ’19, the renowned literary critic, editor, and author, who during the Great War took a year off from Harvard to drive an ambulance in France.

In Exile’s Return, his luminous memoir of the “Lost Generation” of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Cowley reflected on our shared alma mater:

A Jewish boy from Brooklyn might win a scholarship by virtue of his literary talent. Behind him there would lie whole generations of rabbis versed in the Torah and the Talmud, representatives of the oldest Western culture now surviving. Behind him, too, lay the memories of an exciting childhood; street gangs in Brownsville, chants in a Chassidic synagogue, the struggle of his parents against poverty, his cousin’s struggle, perhaps, to build a labor union and his uncle’s fight against it—all the emotions, smells and noises of the ghetto. Before him lay contact with another great culture, and four years of leisure in which to study, write and form a picture of himself. But what he would write in those four years were Keatsian sonnets about English abbeys, which he had never seen, and nightingales he had never heard.

Cowley’s well-spun stereotype captures my own Harvard experience, mutatis mutandis. Abbeys I didn’t write about, but I warbled medieval motets and Christmas carols in the glee club under the baton of Elliot Forbes, a great-grandson of Ralph Waldo Emerson. I was a million miles from the Flatbush ghetto, drinking deep of the Harvard mystique. In retrospect, I morphed into a metaphorical Marrano, goyish-by-association on the outside, steeped on the inside in Jewish language and lore. I read the Greeks and New Testament, Milton and T. S. Eliot, and inhaled the heady humors of New England transcendentalism. Rubbing elbows with the elegant critic on the stairs was the perfect topper to my gentrification.

As a freshman in 1965, I worked 10 hours a week wheeling a wooden cart through the labyrinthine stacks of the mammoth Widener Library, pausing frequently to peruse the cornucopia of books that I was paid bupkis to reshelve. Musty and claustrophobic, the stacks were Shangri-La for a yeshiva boy on the run. During the fiftieth reunion, I played hooky from the marathon of cheerful reacquaintance (hello to Al Gore ’69, fellow denizen of Dunster) and earnest panel discussions (“Navigating Later Life,” “We Were Going to Change the World—What Happened?”), and retreated for an afternoon to Houghton Library, home to Harvard’s collection of rare books and manuscripts. Here, on a visit to Boston several years ago, I examined a kabbalistic text belonging to Judah Monis (1683-1764), the first Jew at Harvard.

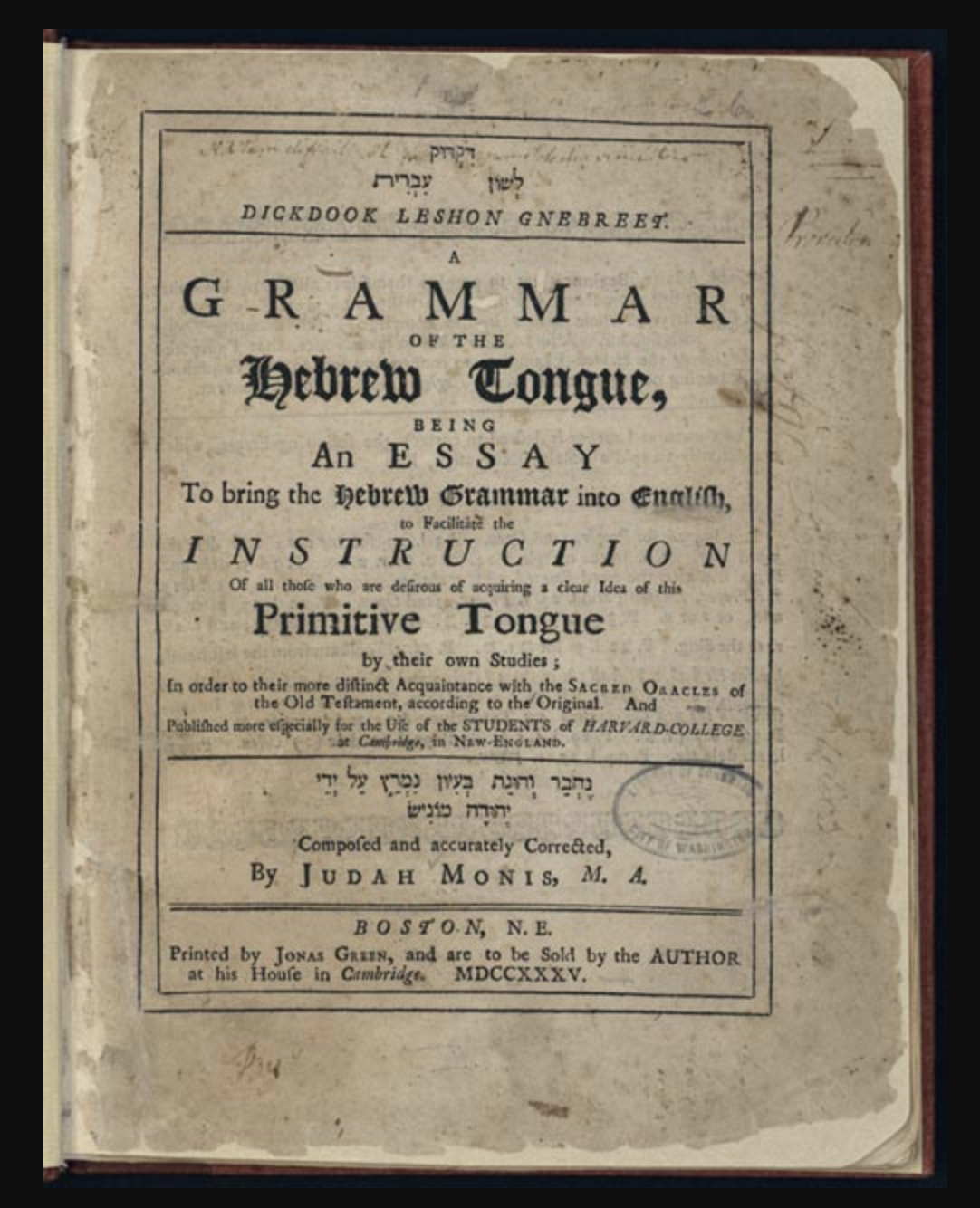

Back in 1964, the Carolina Jewish wit Harry Golden, regarding the Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, famously quipped that he “always knew the first Jewish President would be an Episcopalian.” So too Harvard’s first Jew. The author of a Hebrew grammar, Monis was publicly baptized at the College Hall in 1722, and promptly joined the faculty. He observed the Christian Sabbath on Saturdays, giving rise to suspicion, and for 38 years taught mandatory Hebrew to rebellious students. In the spring of 1966, I quit my job at Widener for a better-paying gig teaching Hebrew to balky bar mitzvah kids in suburban synagogues.

Now, in the Houghton reading room, I had a look at the biographical sketch of Judah Monis (MA, 1723) in Volume VII of Sibley’s Harvard Graduates (1945). It was mostly familiar stuff: born in Italy or maybe Algiers, might or might not have been a rabbi, had lived in Jamaica, New York, or possibly Jamaica as in Bob Marley. I’d read a fair bit over the years about this intriguing, enigmatic forerunner but had forgotten that the Hebrew teacher ran a small business on the side:

As soon as Monis was established in Cambridge, he undertook “a Mighty Stroke at trading” in the form of a general store. Far from regarding this as below the dignity of a member of the Harvard faculty, the Cambridge townspeople admired his enterprise and came to be very fond of him. The College authorities found the store useful and patronized it for pipes, tobacco, nails and the like. Sharp as they were, the Yankees were no match for the former rabbi. In 1736, the Brattles, Trowbridges, and Gookins had to combine to get the Cambridge innkeeper out of his economic clutches, and in the next year, he had the Sudbury innkeeper, whose friends were less influential, jailed for debt.

My goodness! Was Clifford K. Shipton, the longtime Harvard archivist and author of Sibley’s profiles, casting Judah Monis as Shylock? But if so, which one: the lucre-loving Olivier of Britain’s National Theatre or Al Pacino in the revisionist film of 2004, taking no guff from goyim, a kickass Shylock even the ADL could love? More research was called for. Shipton’s New York Times obituary of 1973: “In an address delivered here at the 1966 meeting of the American Historical Association, Dr. Shipton linked ‘the Puritan version of the Hebraic contribution and that of the modern Jewish immigrants’ as the two most significant factors in determining the character of American culture today.” A JSTOR search turned up a 1958 article by Clifford Shipton from the American Jewish Historical Quarterly entitled “The Hebraic Background of Puritanism.” Here he tweaks his friend and Harvard colleague Perry Miller, doyen of American intellectual historians:

[I]n his great book on the New England Mind, [Miller] remarks that the Puritans were first and foremost heirs of St. Augustine. That is true in the sense that we are all heirs of the great minds of the past. But it is also true that not one Puritan in a hundred had ever heard of St. Augustine, whereas he was as familiar with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as he was with the members of his own family.

Avraham Avinu? Some might call it cultural appropriation, but Christian Americans have long imagined themselves to be the Chosen People:

The Puritans regarded the post-Biblical Jews as a misguided splinter-group which differed from themselves, the true sons of Abraham . . . Living Jews were regarded with great interest because they were the custodians of Hebraic culture . . . One frequently detects a note of envy of the fact that Jews could speak Hebrew, the difficult language which the Yankee must learn before he could in Heaven converse with his Biblical fathers.

“Living Jews” like Judah Monis, melamed to the Yankees, and a representative man in the Emersonian sense: an immigrant to American shores who did what it took to fit in and make ends meet.

Flashback to June 5, 1967. I was hurrying to the Dunster dining hall for a quick breakfast before my final exam in solid-state physics (“for poets”). I ran into a fellow sophomore, a Gentile from California who broke the news: “Grab your gun, Schoffman, your country is at war.” Today that would smack of anti-Semitism, an accusation of dual loyalty. Then, it meant nothing of the kind, or so I assumed. I bolted to my room and caught a snatch of radio coverage, then raced through the exam, leaving an hour early. Luckily, I was taking the course pass-fail. I used to say that if the Six-Day War had lasted for six weeks, I might well have gone over to volunteer, grab a gun, maybe drive an ambulance, and never returned to Harvard. Had I settled in Zion at 19 and not 41, today I’d be a full-blown Israeli, mutatis mutandis.

Instead, half a century later, 5,500 miles from my home in Jerusalem, I found myself marching, together with hundreds of fellow septuagenarians of ’69, to plum seats in historic Harvard Yard, to witness the commencement speech delivered by Angela Merkel. The tactful European leader made no direct mention of American politics. “If we break down the walls that hem us in, if we step out into the open and have the courage to embrace new beginnings, everything is possible,” said Merkel, a PhD in physics, recalling her earlier life in East Berlin, in the shadow of the Wall. The huge throng of graduates, alumni, and guests rose to their feet and cheered her message of hope in a darkening world. I was moved to the marrow at the sight of a German chancellor, a friend of Israel, alongside Lawrence Bacow, Harvard’s haimish Jewish president, the son of an Auschwitz survivor. When he took office in 2018, Bacow affixed a mezuzah to the doorpost of the president’s official residence and kashered the kitchen. I’d like to imagine that Judah Monis, the Massachusetts Marrano, was somewhere upstairs, wiping a tear.

Suggested Reading

Walking the Green Line

New books about the settlers and the settlements and depth and nuance to the discussions about their existence.

Cognitive Dissonance

Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future. His proposal may surprise you.

Blocked Desire

The Tunnel, A. B. Yehoshua’s most recent novel, written as he moved into his eighties, does not exhibit any traits of what some literary critics have called “the style of old age,” but its unusual subject, incipient dementia, is patently a concern of old age.

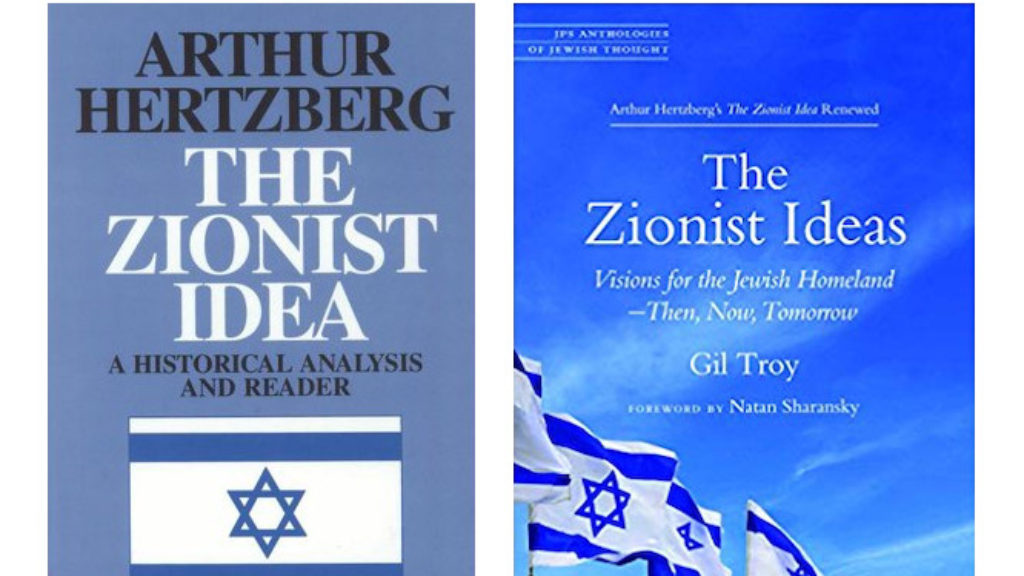

Zionisms Abound

Gil Troy and Allan Arkush on Troy’s new book, The Zionist Ideas.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In