Nothing but Blue Skies

In 1932, when an aesthete from Iowa named Carl Van Vechten was visiting Vienna, he reported back home that “they don’t play Johann here anymore; it’s all Gershwin and Berlin.” Such exaggeration was defensible. American popular music had already been circumnavigating the globe for about two decades. That same year Arthur Koestler was staying in a guesthouse in the Soviet republic of Turkmenistan, with Langston Hughes occupying the room next door. Through the wall, Koestler could hear a gramophone playing Sophie Tucker’s “My Yiddishe Mame” (words by Jack Yellen, music by Jack Yellen and Lew Pollack). This ballad, which Tucker made her signature, exemplified an explosion of talent—almost entirely Jewish—that was unprecedented in the history of the nation’s music. Who deserves the most credit for such ubiquity, for such enchantment? Who were the very greatest songwriters of the last century? The jury is still out. Jerome Kern, the Gershwins, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, Cole Porter, and Stephen Sondheim all have their champions among musicologists, as well as the devotees of Broadway. But which of these composers and lyricists happens to have led the most astonishing life? The answer to that question is inarguable: Irving Berlin, who was born in Tyumen in Siberia in 1888 and died in New York in 1989.

That he lived to a ripe 101 can be dismissed as an actuarial accident. But consider: Berlin was generating Tin Pan Alley hits before Ronald Reagan was born and was still writing lyrics when the elderly Reagan occupied the White House. He died after Reagan left office. In his 1917 novel The Rise of David Levinsky, Abraham Cahan already has his protagonist, a textile tycoon, muse that another Russian Jewish immigrant was creating the songs that all of America was singing. This was during the rage for ragtime. But the career of Irving Berlin also ran through jazz and swing before sputtering out in the era of rock and roll and country and western. He lived long enough to hear Willie Nelson sing “Blue Skies,” which reached the top spot on the country music charts. When introduced in a 1926 show called Betsy, the song had required two dozen curtain calls. A year later, when The Jazz Singer broke the sound barrier, “Blue Skies” was the first song that audiences around the world heard Al Jolson sing. Longevity enabled Berlin to write the words and music to a whopping 899 copyrighted songs. By his own admission, many of them were lousy. But an amazing 35 of his songs hit the top of the charts. Such rankings paid tribute not only to his extended and uncanny knack for satisfying popular taste but also to the mysterious gift that biographer James Kaplan proclaims in his subtitle. Best known for a biography of Sinatra, Kaplan fails to mention that even Stravinsky called Berlin a “genius.”

The 21-year-old Berlin needed only 18 minutes in 1911 to write what became the most popular song in American history up to that time, “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” It is actually a march, not ragtime—not that he cared about distinctions of genre or the fine points studied in conservatories. In fact, this “New York genius” never learned to read or write music. He played almost only the black keys on the piano, tuned to the key of F-sharp, and used a transposing instrument designed with a lever under the keyboard so that he could play tunes in the other keys. To transcribe what he heard in his head for purposes of notation and orchestration, Berlin was therefore obliged to hire secretaries (one of whom was a kid named George Gershwin).

Yet Berlin mastered the trick of achieving simplicity without descending into banality, of making topical songs seem timeless, and of concocting love songs as though no one else had thought of treating romance as a subject. He managed to work so fast that only two months were needed to provide the score for Annie Get Your Gun, which ran for 1,147 performances. Among its unparalleled eight “standards” was “Anything You Can Do,” which Berlin—stalled in a cab in Manhattan traffic—wrote in 15 minutes. Yet perspiration was far more common than inspiration; perhaps no one on Broadway ever worked harder so that the results would seem effortless. (An insomniac, Berlin often worked through the night.) So rapid was his ascent that only 14 years after “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” created an international sensation, Jerome Kern famously declared Berlin to be synonymous with American music itself. He was still just 36 years old when he acquired his first biographer: Alexander Woollcott, of the Algonquin Round Table. Kaplan is the latest in the queue, though he lacks the musicological insights to match Laurence Bergreen’s much fuller saga, As Thousands Cheer.

Berlin’s versatility was downright eerie. Paramount’s 1942 film Holiday Inn is set primarily in a New England inn open only on public holidays, including the one that celebrates the birth of the Savior. Only a weekend was needed to write the movie’s most famous song. No American Jew—no ACLU attorney, no jurist committed to a high wall of separation between church and state—ever did more to desacralize society than did Irving Berlin. For Americans dreaming of a white Christmas, the theological dimensions of that holiday could easily recede into a democratic ecumenism, and even Americans unable to accept the historical actuality of the Resurrection could blend into an “Easter Parade.” Berlin placed his own faith in the validity of popular taste; he could not imagine any artistic ideal independent of the marketplace. “The mob is always right” was the credo that Berlin honored without ambivalence (and even when the mob was no greater than a tryout audience in New Haven). But because mass taste fluctuates, he had to adapt to ever-changing trends.

Virtuosity was Berlin’s response to fickle popular judgments, and one consequence was the absence of a distinctive musical signature. That he had grown up in a Yiddish-speaking home on the Lower East Side accounts for the early, satiric melting-pot songs, replete with the stereotypes clinging to the Italian, Irish, and Jewish newcomers. But what, other than his genius, explains the shimmering urbanity and sophistication of, say, “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails,” and “Cheek to Cheek”? So sinuous a line from Berlin’s plebeian origins inspired one observer to marvel at “Park Avenue librettos / By children of the ghettos.”

In beginning the lyric for “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” with “Come on and hear! Come on and hear!” Berlin produced the secular equivalent of the Shema, the “Hear O Israel!” that he would have chanted with his father, a part-time cantor. On the Lower East Side, Moses Baline had to be versatile too. He was also a kosher poultry inspector and a house painter, but he died before his son Israel (Izzy) Baline reached adolescence. Berlin busked, ran away from home for a couple of years, then moved to the fringes of the music industry and eventually into the refuge of Tin Pan Alley. Berlin completely abandoned the practice of Judaism, and Kaplan unsurprisingly finds no significant liturgical influences on Berlin’s music. None of the artists and entertainers who started out in the tenements over a century ago propelled themselves further away from the old neighborhood. Twice married outside the faith, Berlin did not raise his three daughters as Jews.

Berlin is not thereby excluded from Yale’s Jewish Lives series. Along a spectrum of biographies with Rabbis Kook and Schneerson at one end and Benjamin Disraeli and Sarah Bernhardt at the other, Berlin is far closer to England’s Anglican prime minister and France’s convent-raised actress. But oddly enough, this biographer shows even less interest in the Jewish dimension of Berlin’s prodigious career than he himself did. (The endnotes cite no works in American Jewish history.) And yet for those who knew Berlin from the Lower East Side, he was still the homeboy Izzy; in 1959, a decade after his given name also became the designation of a new state in the Near East, Berlin celebrated with a song entitled “Israel.”

More central to his story, however, is “God Bless America,” which was written in 1918 but was then relegated to his trunk of unreleased songs. That was the same year that Berlin, who had landed in New York at the age of five, became a naturalized citizen. Twenty years later, in the fall of 1938, under the ominous shadow of a war that threatened Western civilization itself, he introduced a revised “God Bless America.” It soon became inescapable, despite arriving a little too late to serve as the national anthem, Congress having already picked “The Star-Spangled Banner” seven years earlier. Nevertheless, in the fall of 1954, when the American Jewish Tercentenary Dinner was held in New York, with President Eisenhower delivering the main address, Berlin highlighted the gala by singing “God Bless America.” For someone who claimed that his earliest memory of tsarist Russia was the shock of a pogrom, the composition of this song seems overdetermined. That a believer in the nation’s majority faith is unlikely to have written “God Bless America” is evident in the sort of deity that Berlin invokes. In asking that the nation be given divine guidance and protection, the song leaves no one out (except for atheists and agnostics) and certainly doesn’t exclude the Jews. Contrast Berlin’s lyrics with those of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” and “America the Beautiful,” both of which stem from Protestantism and mention the Pilgrims. “God Bless America” betrays no hint of the existence of any particular faith. Its blessings are nondenominational. At least by inference, everyone in Berlin’s America should feel at home; no one should feel an outsider.

Within the historical limits of Berlin’s long life, he could be considered liberal on the race question too; perhaps his Jewish roots have something to do with that sensitivity. To be sure, his early catalog included what were then called “coon songs,” and he waited too long to detach himself from the vaudeville tradition of minstrelsy. But news reports of the violence inflicted upon black southerners impelled him to write a poignant indictment of lynching called “Supper Time,” which Ethel Waters sang in the 1933 Broadway revue As Thousands Cheer. That was six years before Billie Holiday made famous Abel Meeropol’s more searing “Strange Fruit.” In As Thousands Cheer, Waters was stuck with a lesser billing because she was black, but the four songs that she sang in that revue buttressed her later claim that no one ever gave her better material than Irving Berlin. A decade after that revue wowed Broadway audiences, a segregated military fought the Axis powers. Minor breaches of Jim Crow were permitted only at the very end of the war, but in This Is the Army, Berlin’s 1943 wartime revue, he made sure that the touring company of the show was fully integrated. It was the army’s only such unit until President Truman ordered the desegregation of the armed forces in 1948. But as Berlin would later write, “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

And it was a business, which Berlin conducted with considerable shrewdness. He proved to be a zealous guardian of the rights to his oeuvre, carefully monitoring how his genius could be converted into a revenue stream. Yet he was capable of remarkable gestures of generosity, such as assigning the royalties of “God Bless America” to the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts, and sending the proceeds from This Is the Army to the Emergency Relief Fund. But Berlin also operated in an environment notable for its competitiveness. Even the figure responsible for more hit songs than any other American had ever written could sense the fragility of success, the danger of missing the next sudden shift in the popular mood. Berlin found revues, which are star-driven, more congenial than what he called “situation shows,” the seamless integration of plot, character, music, and dance. With Annie Get Your Gun, he finally achieved that ideal, which is what Broadway audiences had come to expect. By the 1950s the creative juices were drying up, and two decades later, he had turned into a cranky recluse at Beekman Place, conducting his business by telephone. George Gershwin, Berlin’s one-time assistant, was fated to live little more than a third as long, but his capacity to write orchestral pieces and even an opera made Berlin look, by comparison, like no more than a spectacular tunesmith. His final decades bring to mind Frost’s “Provide, Provide”: “No memory of having starred / Atones for later disregard / Or keeps the end from being hard.”

Suggested Reading

Valhalla in Flames

To give their "Thousand Year Reich" a patina of tradition, the Nazis co-opted the German and Western European cultural canon.

The Language of Tradition

On tradition as a first language.

Words, Words, Words

The super sad truth about Gary Shteyngart's new novel.

Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

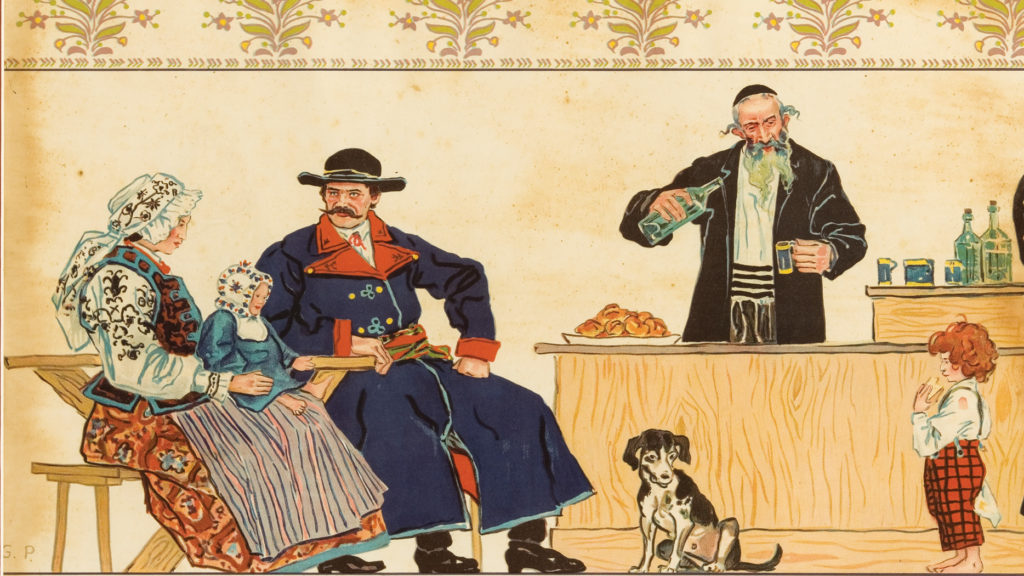

Jewish-run taverns—rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes—served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews, as a new book by Glenn Dynner shows.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In