Famous Jews

Barbra Streisand’s face makes a surreal cameo in Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. In the pristine suite of a luxury hotel, Thompson introduces us to Lucy, a runaway obsessed with painting Barbra.

Lucy . . . was lying on the patio, doing a charcoal sketch of Barbra Streisand. From memory this time. It was a full-fledged rendering, with teeth like baseballs and eyes like jellied fire. The sheer intensity of the thing made me nervous.

Lucy has come to Vegas on pilgrimage to offer Barbra the portraits. The trip is, at the very least, misguided, but Thompson goes further and reminds us of the possible violence inherent in obsession. “What was she going to do when [she read] that Streisand wasn’t due at the Americana for another three weeks?”

I kept waiting for Lucy to appear during the Barbra Streisand chapter of David E. Kaufman’s new and entertaining Jewhooing the Sixties: American Celebrity and Jewish Identity. Kaufman’s book is a packed study of Jewish identity, Jewish celebrity, celebrity in general, celebrity and homosexuality, Jews and homosexuality, and “the challenge of balancing universalist tendencies and particular concerns.” It’s all told through and around profiles of four exemplary Jewish celebrities of the 1960s: Sandy Koufax, Lenny Bruce, Bob Dylan, and Streisand—and the fans who loved them. Remarkably, Kaufman’s book does not collapse under the weight of all these topics, though some are more expertly handled than others. Jewhooing succeeds as a study of Jewish identity and sheds new light on the lives of his four subjects by contextualizing them within the broader contours of American Jewish social history. But it stumbles as an inquiry into celebrity. There is a darkness to ’60s celebrity that touched each of Kaufman’s subjects, which he largely ignores.

I kept waiting for Lucy to appear during the Barbra Streisand chapter of David E. Kaufman’s new and entertaining Jewhooing the Sixties: American Celebrity and Jewish Identity. Kaufman’s book is a packed study of Jewish identity, Jewish celebrity, celebrity in general, celebrity and homosexuality, Jews and homosexuality, and “the challenge of balancing universalist tendencies and particular concerns.” It’s all told through and around profiles of four exemplary Jewish celebrities of the 1960s: Sandy Koufax, Lenny Bruce, Bob Dylan, and Streisand—and the fans who loved them. Remarkably, Kaufman’s book does not collapse under the weight of all these topics, though some are more expertly handled than others. Jewhooing succeeds as a study of Jewish identity and sheds new light on the lives of his four subjects by contextualizing them within the broader contours of American Jewish social history. But it stumbles as an inquiry into celebrity. There is a darkness to ’60s celebrity that touched each of Kaufman’s subjects, which he largely ignores.

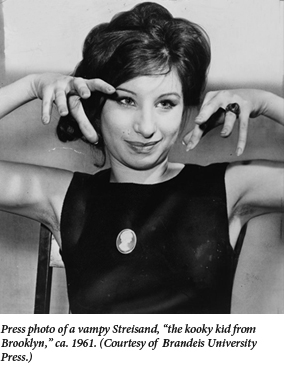

Kaufman’s themes of celebrity and Jewish identity intersect at the point of “Jewhooing,” the game of publicly identifying (or “outing”) celebrities as Jews and then viewing them through that prism. Discussion of a celebrity’s physical appearance is the most obvious form of “Jewhooing.” Streisand’s nose, for instance, was a topic of great interest in the ’60s (“a Brooklyn girl with small, sad eyes and an absurd nose,” reported Newsweek). Kaufman even calls her decision not to have it “fixed” “the equivalent of Koufax’s decision not to pitch on Yom Kippur, the touchstone of her reputation for ethnic loyalty.” But Jewhooing was not just a matter of looks. Take the activity of uncovering Jewish themes in Dylan’s music, a special subdiscipline of “Dylanology.” Thus, in a book entitled Bob Dylan Approximately: A Portrait of the Jewish Poet in Search of God—A Midrash, Stephen Pickering argued that Dylan, embraced a “Martin Buber—like Hasidism,” despite the lack of any explicit evidence.

Yet the core story of Kaufman’s book is not any specific Jewhooing but the complex relationship between celebrities and their public. Jewish celebrity simultaneously represents persistent Jewish difference and “making it” in the wider American society. The Jewish celebrity has succeeded as a Jew, but then again, since he, or she, has made it as a Jew, he or she is at least partly unassimilated. The Jewish celebrity represents what it means to be Jewish to the wider American public, and, in doing so, often helps validate choices about Jewish life and practice.

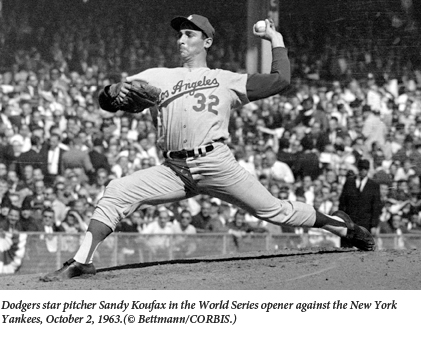

In perhaps the best individual reading in this book of vivid readings, Kaufman deflates the hagiography surrounding Sandy Koufax’s decision not to pitch on Yom Kippur when it coincided with the first game of the 1965 World Series. Hank Greenberg’s earlier decision not to play on Yom Kippur was, Kaufman says, “a harbinger of the turn from ethnicity to religion.” Koufax, on the other hand, played at a time when American Judaism was redefining itself along minimalist religious lines, when being Jewish was widely defined as going to services on High Holidays. Koufax’s decision not to pitch wasn’t an act of religious devotion, but “an affirmation of the status quo.” Koufax later wrote, “There was never any possibility that I would pitch. Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the Jewish religion. The club knows that I don’t work that day.” Tellingly, Koufax wrote “work” instead of “pitch.” He could as easily have been an accountant asking to spend the day with his family. For Kaufman, Koufax’s legendary status among Jews comes not from his personal piety, but for fulfilling the desire to be the insider-outsider: at the pinnacle of American society, but assertively Jewish.

In perhaps the best individual reading in this book of vivid readings, Kaufman deflates the hagiography surrounding Sandy Koufax’s decision not to pitch on Yom Kippur when it coincided with the first game of the 1965 World Series. Hank Greenberg’s earlier decision not to play on Yom Kippur was, Kaufman says, “a harbinger of the turn from ethnicity to religion.” Koufax, on the other hand, played at a time when American Judaism was redefining itself along minimalist religious lines, when being Jewish was widely defined as going to services on High Holidays. Koufax’s decision not to pitch wasn’t an act of religious devotion, but “an affirmation of the status quo.” Koufax later wrote, “There was never any possibility that I would pitch. Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the Jewish religion. The club knows that I don’t work that day.” Tellingly, Koufax wrote “work” instead of “pitch.” He could as easily have been an accountant asking to spend the day with his family. For Kaufman, Koufax’s legendary status among Jews comes not from his personal piety, but for fulfilling the desire to be the insider-outsider: at the pinnacle of American society, but assertively Jewish.

This is interesting, even brilliant, but the argument slips when Kaufman tries to put Koufax back together again. The insider-who-is-also-an-outsider duality becomes his key to viewing all things Koufax. Kaufman writes that Koufax was Jewhooed as the intellectual anti-athlete, but instead of challenging the premise, Kaufman describes Koufax as the missing link between the egghead nebbish who seduces the girl with brainpower and overcompensating, macho Jews like Norman Mailer. Koufax, Kaufman writes, “projected an image of Jewish masculinity that was as much the mild-mannered Clark Kent as it was the muscle-bound Superman.” But this requires a substantial revision of the historical record. Unlike Norman Mailer and Woody Allen, Koufax did not make sex part of his public persona. In fact, its absence fed the 2002 rumor, published by the New York Post, that Koufax was gay. Kaufman skims over the Post story, seeing it as a continued “othering” of Koufax, but neglects to note that such rumors are typical of the dark side of celebrity.

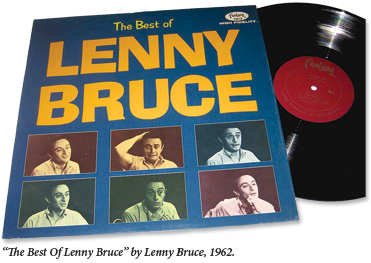

The Koufax chapter is emblematic of the book as a whole. Kaufman is not a biographer. He doesn’t conduct new interviews with his subjects or perform new archival research, instead he reinterprets the existing record. In a nod to the haggadah, Kaufman sees our celebrities through the prism of the four children. Koufax and Streisand are the “good” children. Where Koufax was the insider-outsider, Streisand was the figure who used Jewishness to become famous. Lenny Bruce points to an irreverent Jewishness that calls on lingering marks of ethnic difference, while Dylan represents the “extraordinary urge to escape from Jewishness . . . and the extraordinary urge of others to see him as a Jew.” Kaufman even calls both Bruce and Dylan “‘the wicked son,’ as it were.” This doesn’t tell us much about the actual lives of Kaufman’s subjects, but it does illuminate their public personae and shows how their attempts to manage their lives clashed with their fan’s desires. No matter how interesting Koufax, Bruce, Dylan, and Streisand may be, the interpretations and analysis they’ve received are equally fascinating, if not more so. Kaufman goes on for pages (yes, pages) on whether calling Barbra Streisand “kooky” is code for “Jewish.”

irreverent Jewishness that calls on lingering marks of ethnic difference, while Dylan represents the “extraordinary urge to escape from Jewishness . . . and the extraordinary urge of others to see him as a Jew.” Kaufman even calls both Bruce and Dylan “‘the wicked son,’ as it were.” This doesn’t tell us much about the actual lives of Kaufman’s subjects, but it does illuminate their public personae and shows how their attempts to manage their lives clashed with their fan’s desires. No matter how interesting Koufax, Bruce, Dylan, and Streisand may be, the interpretations and analysis they’ve received are equally fascinating, if not more so. Kaufman goes on for pages (yes, pages) on whether calling Barbra Streisand “kooky” is code for “Jewish.”

But if Kaufman is right that celebrity is best understood as a relationship between the famous and the rest of us, can we really ignore the darker aspects of that relationship, the way that public celebration leads to public denunciation, and the threat, even the reality, of physical violence?

In January 1971, A. J. Weberman, a Yippie, and possibly the inventor of Dylanology, led a group of students to Bob Dylan’s home in Greenwich Village to protest Dylan “and all [he’d] come to represent in rock music.” A year later, Dylan shoved Weberman on the streets of the Village. Weberman had promised to stop going through Dylan’s trash but had not. “I deserved it,” Weberman told The New York Times in 2006. In a final, bizarre turn, Weberman convinced Folkways Records to release an LP of a phone conversation with Dylan that he illicitly recorded: Bob Dylan vs. A.J. Weberman: The Historic Confrontation. Kaufman acknowledges that some have questioned Weberman’s sanity, but refers to the album as “nonetheless a rare instance of a direct encounter between a superstar and a hardcore fan. It is also a dialogue between two Jews.” It is also stalking.

It is easy to dismiss such encounters, but all celebrity culture thrives on this root fascination with the famous. To be a celebrity is to see rumors about one’s sex life and public commentary on one’s every action printed in various media. Kaufman ends his Lenny Bruce story in the early 1960s, with Bruce more or less still ascendant. The legal troubles had begun, but they had not yet consumed Bruce’s life. But they did, in fact, consume his life: Bruce went from famous to notorious. His stage act degraded into readings of court transcripts and the charges against him. In a vicious cycle, his notoriety attracted more charges and more notoriety.

Celebrity is an endless dialogue about appearance, manifested in plastic surgeries and eating disorders. Jews may have taken pride in Barbra Streisand’s nose, and one of Streisand’s achievements may well have been, as Kaufman writes, helping to make “Jewishness aesthetically attractive and romantically appealing in 1960s America,” but this is only the “positive” side of what is a fundamentally unhealthy fixation on the body. Life magazine even once speculated that “it may be only a matter of time before plastic surgeons begin getting requests for the Streisand nose.” In the words of Cintra Wilson’s brilliant book title, celebrity is a “massive swelling” that ought to be “reconsidered as a grotesque, crippling disease.”

Celebrity is, at its very core, an erasure of private life. Not surprisingly, this turns out to have peculiar Jewish implications. Kaufman is unsure what to make of Dylan and whether to call him a Jewish artist. Bob Dylan famously ran from and obscured his origins as Robert Zimmerman, but, as Kaufman acknowledges, this was less assimilation than an effort to connect himself to Woody Guthrie and American folk mythology. It’s what ultimately leads Kaufman to conclude that Dylan tries to escape from his Jewishness but in a way that appeals to Jews.

There is a counter-narrative to this story. Many who know Dylan have reported his deep interest in religion. Dylan’s brief phase as a born-again Christian even testifies to a sustained grappling with faith. I won’t pretend to understand Dylan’s personal, interior religion, but the public struggle over Dylan’s faith and the desire to see his songs as religious represents a demand that Jewish celebrities be publicly Jewish. We Jews deny—or at least denied—our celebrity the right to be a man in the street and a Jew at home.

Although it has its faults, Jewhooing the Sixties is never less than engaging. Kaufman has a provocative scholarly voice and his book raises interesting questions. After reading it, I wondered what the story of celebrity and Jewish identity would look like if we changed the variables. What if we pursued the story of Jewish celebrity without the goal of celebrating Jewish achievement? And could Kaufman have sustained his narrative if he had extended the time frame into the late 1960s, after the Manson murders? The early 1960s were, after all, not only a period of flux in the Jewish community. They were perhaps the last time the encounter with celebrity could be cast in such innocent terms. Meanwhile, Dylan is still releasing new albums and Streisand appears to be in the midst of a career renaissance. How are they “Jewhooed” now and what does it say about American Jewish life in the 21st century?

Suggested Reading

On a Story by Delmore Schwartz

In 1937, the editors at Partisan Review placed “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” by a 24-year old unknown improbably named Delmore Schwartz before pieces by Wallace Stevens, Lionel Trilling, Edmund Wilson, and Pablo Picasso, to relaunch their magazine. They knew what they were doing.

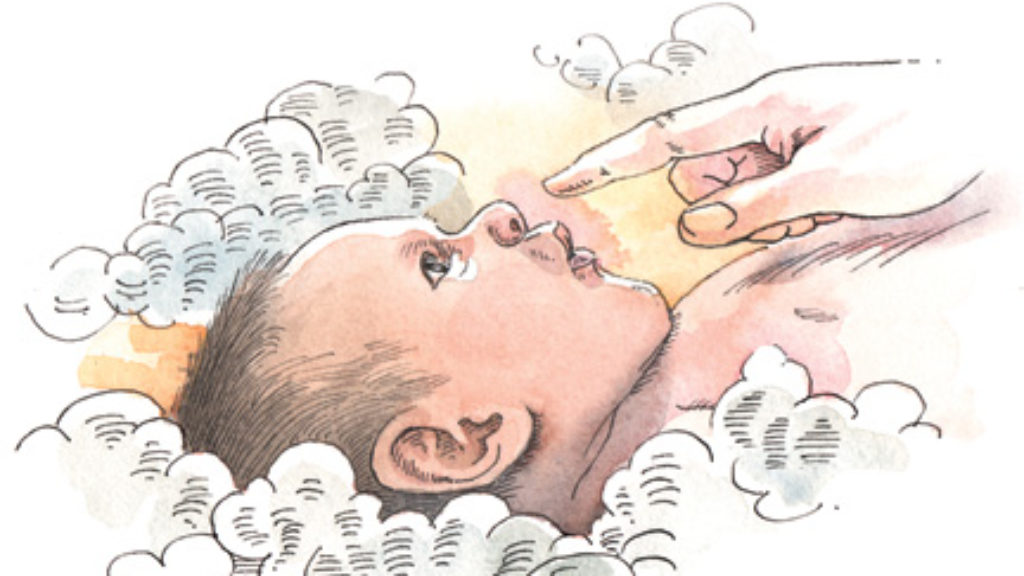

How the Baby Got Its Philtrum

The idea of learning as a recovery of what we once possessed is what makes Bogart’s bubbe mayse, and ours, so memorable: We can all touch that little hollow and feel the impress of forgotten knowledge.

Wishful Republic

What lessons can be learned from the city of Haifa, and what does its culture suggest about the likelihood and limitations of a binational state?

And One for All

Adam Sutcliffe is an intellectual historian, not a theologian or a philosopher, so he doesn’t try to answer the question of what purpose Jews serve in the world, but he has a lot to say about the attempts to do so that Jews and non-Jews have been making for ages.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In