And One for All

Adam Sutcliffe’s book is not about the things Jews are for, as opposed to what they are against. Instead, it focuses on what he calls, in one of his few slips into inelegance, “the Jewish purpose question.” Sutcliffe is an intellectual historian, not a theologian or a philosopher, so he doesn’t try to answer the question of what purpose Jews serve in the world, but he has a lot to say about the attempts to do so that Jews and non-Jews have been making for ages.

For traditional Jews, the question of “what they were for” was, to be sure, far less important than the question of what their duties were, but they did ask it, and when they did, it took a theological form: Why did God single out the Jews and make his covenant with them? The medieval poet and philosopher Yehuda Halevi, Sutcliffe writes, “ascribes to the Jews a vital role both in sustaining all humanity and in ultimately bringing it most profoundly close to God.” Halevi thought that Jews actually possessed an ineffable connection to God that made them different from, and responsible for, their fellow human beings. Not long afterward, the great jurist and rationalist philosopher Maimonides saw the “specialness of the Jews” as being connected with “their philosophically established dual mission: to know and to worship God.” For Maimonides, in short, it was not about Jews, who were no different from anybody else, but about Judaism and the truths it preserved.

Sutcliffe briefly outlines these and other classical Jewish explanations of the Jews’ role in the world, but he is not really interested in exploring them thoroughly. Nor beyond a brief exposition of Augustine’s doctrine of witness—the idea that continued Jewish existence and misery in exile testifies both to the authenticity of the “Old Testament” and to Jewish guilt for having rejected the new one—does he have much to say about classical Christian answers to the question. What he tells us about the thinkers of antiquity and the Middle Ages is little more than what we need to know to grasp how modern—religious as well as secular—thinkers have recycled, revised, or rejected their ideas.

Twenty years ago, Sutcliffe published a superb volume on the Enlightenment and the Jews, and he has since then written widely and instructively on modern Jewish thought (and modern thought about Jews). In What Are Jews For? he draws on his previous research and expands it, but his book is not just a collection of case studies. Above all, it is an effort to encourage Jews to continue to think about their purpose in the world. For even if the question cannot be answered, he believes it leads to the sort of discussion that brings out the best in us, and through the very act of reflecting on it, we can, as it were, be “a light unto the nations.”

During the era of the Enlightenment and the early decades of the 19th century, leading French and German thinkers, including the few who held positive views of Jews, generally agreed on the obsolescence of Judaism and the pointlessness of Jewish survival. “At first a significant number of Jewish intellectuals shared this view,” but, Sutcliffe writes, “the idea of Jewish purpose was soon reasserted with new vitality and vigour.” The spokesmen for Reform Judaism in particular, but others as well, maintained that Jews were “the guardians of the spiritually purest form of religion and ethics,” who had the “mission” of disseminating “true ethical universalism through all humanity.” Thus, “the casting of Jews as teachers was the central nineteenth-century answer to the Jewish purpose question.”

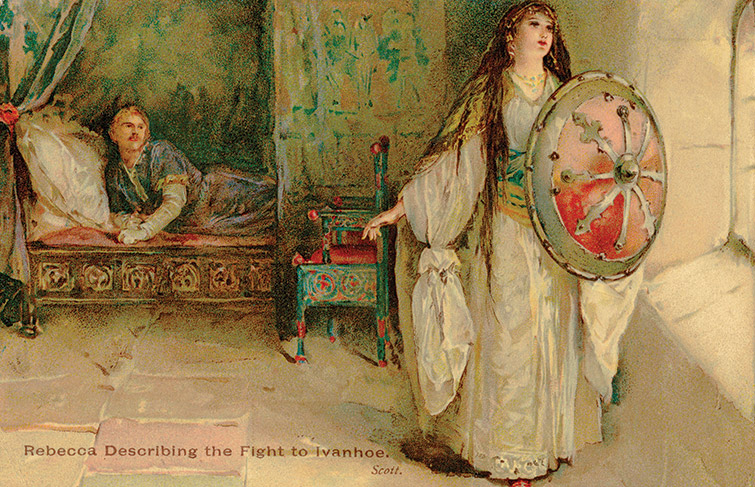

A very different answer emerged in 19th-century British fiction, especially in the works of Sir Walter Scott and the Jewish writer Grace Aguilar. In Ivanhoe, Scott’s beautiful Jewish heroine Rebecca “heals, consoles, and wins the love of the eponymous knightly hero” but finally renounces that love in order to stay true to her faith and to allow Ivanhoe to marry the Saxon princess Rowena, bringing unity to England. Rebecca thus embodies what Sutcliffe calls “the ideal of Judaic virtuous tenacity.” If the Reform answer held echoes of Maimonides (minus the halakha), Scott’s Rebecca sounds a bit like a gentle version of Augustine’s witness: a Jew whose loyalty to a flawed faith ultimately vindicates Christianity.

The early 20th-century German economist and sociologist Werner Sombart’s answer had nothing to do with theology. In his bestseller, The Jews and Modern Capitalism, Sombart argued that Jewish bankers and traders were the bearers of capitalist modernity. As Sutcliffe shows, the book can be understood as an appreciation of the Jews’ role in advancing economic well-being—and that’s probably how Sombart meant it before his late-in-life enlistment in the Nazi cause. Another early 20th-century German sociologist (of Jewish origin but baptized at birth), Georg Simmel, argued that the Jewish trader “readily becomes a teacher, because this economic role fosters the mental outlook of rationalism and objectivity that enables the clear-sighted explanation to others of the workings of society.” Thus, Sutcliffe notes, “despite its apparent absolute secularism, Simmel’s argument also rearticulates the fundamental messianic structure of Jewish purpose.”

Early secular Zionists generally renounced the idea that the Jews required a larger justification for their existence; Jews were a people like any other and needed no rationales for being, theological or otherwise, but this wasn’t the only position. Sutcliffe analyzes the views of those who disagreed, from the mid-19th-century proto-Zionist Moses Hess, to the cultural Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am, to Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. Hess hoped that a Jewish state in Palestine “would bring about the regeneration of humanity.” Ahad Ha’am (whom Sutcliffe, in a rare error, identifies as the son of a rabbi) rejected “the outward-oriented pedagogic interpretation of the Jews’ ethical mission” as some kind of moral exemplar for the world but kept a “lofty notion of Jewish purpose and enshrined it as the moral core of his inwardly-directed vision of cultural Zionism.” Nevertheless, however inner-directed and parochial this vision may have been, “Ahad Ha’am fervently believed that Jewish values demanded fair treatment of others,” above all the Arabs of Palestine. For Ben-Gurion, who constantly reiterated the idea of a Jewish nation reborn on its own soil and serving as a “light unto the nations,” the “dual nature of this vision of redemption, oriented both inwardly to the Jewish people and outwardly to all humanity,” was of crucial importance, even if he viewed his Arab neighbors less sympathetically than Ahad Ha’am did.

The same Ben-Gurion played a large part, however, in creating the conditions for a very different answer to the Jewish purpose question. His staging of the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 became the catalyst for the emergence of the Holocaust “as a focus of public attention and increasingly a touchstone of historical meaning.” According to Sutcliffe, the resulting concentration on Jewish suffering in the diaspora gave new strength to the idea that guaranteeing the “survival and protection of the Jewish state” was the primary purpose of the Jews. Especially since Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, Sutcliffe writes, “universalistic and irenic conceptions of Zionism have increasingly been pushed to the margins of Israeli and wider Jewish politics.” In many quarters, they have “been supplanted by a predominantly inward-looking and self-interested understanding of Jewish purpose, espoused most assertively by contemporary messianic religious Zionism.”

Sutcliffe also has a great deal to say about “progressive Jewish universalism,” from the “non-Jewish Jew” and Trotskyite Isaac Deutscher to contemporary American preachers of tikkun olam. These days, most such progressives have given up on Israel as a moral beacon and turned to “what remains of the non-Zionist diasporic and universalist Jewish Left.” This leftist remnant has not lacked for critics. Sutcliffe takes up British writer Jonathan Neumann’s recent polemic To Heal the World?: How the Jewish Left Corrupts Judaism and Endangers Israel. Neumann, according to Sutcliffe, accuses them “of a hypocritical rejection of their own particularity, while celebrating diversity in others; a special hostility to Israel; and abandonment of the true duty and purpose of Jews, which is to support or live in Israel, and to prioritize the security and welfare of Jews in the diaspora.”

Sutcliffe himself remains somewhat distant from the ideological fray—almost above it. A note of criticism does intrude, however, into his discussion of one of the most famous universalists: the recently deceased literary critic George Steiner. Sutcliffe does not object, as have innumerable Zionists over the years, to Steiner’s coolness toward the Jewish state and his idealization of Jews as cosmopolitans whose homeland was a portable text (and not necessarily a Jewish one). He appreciatively acknowledges that Steiner provided “the most sustained and elaborated contemporary secular rearticulation of the traditional nineteenth- and twentieth-century themes of Jewish purpose.” The problem for Sutcliffe is that Steiner divorced these themes from any element of messianism and thus left it unclear whether “any ultimate purpose is served, either for Jews themselves or for the world as a whole,” by the Jews’ “idealistic intensity.” Steiner, says Sutcliffe, lacked “a vista of hope.”

Sutcliffe isn’t a messianist, but he does hope that Jews will continue to discuss the purpose of their own existence, which means, first of all, that they must remain Jews. As long as they do so, they can continue to ruminate about the purpose of their peoplehood in a way that can be of benefit not only to themselves but to the world as a whole. For the ideal of a lofty ethical peoplehood to which some of them give voice is one that can direct everyone “toward the possibility of a future in which we, as part of whatever collectivity we might feel we belong to, might be something more than we are in the present, and part of bringing about a different and better world.”

While Adam Sutcliffe’s intellectual history may alienate some of those intellectuals at whom he here seems to be gently shaking his finger, others—including many who disagree with each other about almost everything else—may nod in agreement with his conclusions. It is refreshing to see a well-informed and thoughtful author survey our current internecine altercations and place them in a broad historical perspective, without attempting to scold his adversaries and win the day. One hopes that Sutcliffe is correct when he asserts, at the very end of his book, that “the Jewish purpose question still spurs us to think beyond our differences, and always to carry on hoping.”

Suggested Reading

Workday Jews

In their respective books, Chad Alan Goldberg and Eliyahu Stern address the question of whether the Jews are the quintessentially modern people or a people who came to modernity late and with a sudden shock. They reach very different conclusions.

A Life of Dialogue

Martin Buber’s call for a “Jewish renaissance” provided a generation of young Jews estranged from their heritage with a vision of Judaism they could identify with.

Moses and Hellenism

In a provocative new work recently published in German, Bernd Witte proposes nothing less than an “alternative history of German culture,” as the subtitle of his finely wrought work of scholarship tells us. Moses and Homer: Greeks, Jews, Germans is a historical and cultural argument animated by powerful indignation. This history, he insists, has yet to be fully confronted.

Tradition, Creativity, and Cognitive Dissonance

What are the conditions for a Jewish intellectual renaissance? Disagreement is one, inconsistency might be another; look at the early Zionists.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In