A Student-Centered Tradition

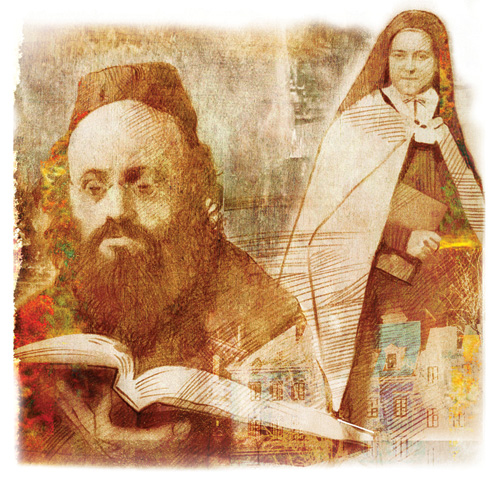

In the early 1930s, John Dewey, America’s leading philosophical pragmatist and a founding father of progressive educational theory, retired from Columbia University. By then, his Copernican revolution in education was well under way. The child, with his individual needs, was now at the center of a new educational universe, and the idea of the child’s formation guided by the wisdom embedded in a tradition was banished to the periphery. In those same years, half a world away in Warsaw, Poland, a Hasidic rebbe was writing his own educational primer on the primacy of the individual student. If, in the West today, Dewey’s progressive legacy is deeply contested—the current state of the American public schools, heavily influenced by his ideas, is decidedly not pretty—the teachings of Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira, the martyred Rebbe of Piaseczno, are regarded as foundation stones for a contemporary renaissance in Jewish pedagogy and spirituality by a wide range of readers.

Recent attention to the Piaseczner, as Rabbi Shapira was known, attests to his enduring appeal. His writings are featured in the schmussen and on the shtenders (lecterns) of yeshivas of all stripes. He has even entered contemporary literature as the protagonist’s third great father figure, along with Freud and Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, in Joseph Skibell’s novel, A Curable Romantic. Some of this attention stems from Shapira’s dramatic life: He was a prodigy, a polyglot, and the last scion of a Polish Hasidic dynasty whose startlingly original theological voice was silenced in the Holocaust.

Born in 1889, the young Kalonymus Kalmish assumed the role of rebbe and community leader in Piaseczno at the age of twenty. His own education had been decidedly traditional, but he was also known and admired in the wider Warsaw Jewish community for his talent on the violin, his medical knowledge, and his deep human insight, as well as his unquestioned mastery of the rabbinic canon. It is possible, but not likely, that he read Freud (Zamenhof is even less likely). In any case, Rabbi Shapira was certainly aware of the recent revolutions in psychology. Nehemia Polen, author of The Holy Fire, a powerful study of the Piaseczner’s Holocaust writings, relates a story of one of the Piaseczner’s hasidim who came to the Rebbe complaining that his headaches had returned ever since the Rebbe’s prescription had faded. When Rabbi Shapira wrote a new prescription, the Hasid placed it firmly in his hatband. To amused onlookers, Rabbi Shapira gently explained, “the modern world would classify this as ‘suggestion,’ but we who hold fast to the way of the Baal Shem Tov call it emuna peshuta—simple faith.” This ability to address the particular person and moment was central to both his charisma and his approach to education.

Until her untimely death in 1937, Rabbi Shapira’s wife, Rachel Hayyah, was a full partner in his projects, reviewing manuscripts, making notes, and raising critical questions that his followers might have been too reticent to pursue. With the outbreak of the war and the German invasion of Poland in 1939, more personal loss would follow in devastatingly quick succession. First, Rabbi Shapira’s only son and most trusted disciple, Rabbi Elimelekh Ben Zion, was mortally wounded by shrapnel during an air assault. A second bomb fell on the hospital entrance, killing both Rabbi Elimelekh’s young wife and aunt. Amidst all this horror, the Piaseczner’s religious and pastoral leadership continued unabated.

When the Nazis established the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, the Rebbe’s home became a haven for refugees. With the help of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, he managed a soup kitchen serving fifteen hundred people daily. With the German closure of the Ghetto’s mikvaot, the Rebbe raised funds to ensure that the mikvah in nearby Piaseczno was heated daily and made available for the women of Warsaw. In 1942, the Piaseczner’s daring and increasingly anguished theological writings finally ceased, and he apparently buried them near his home before being deported to the Trawniki labor camp outside Lublin. Eyewitness accounts from Trawniki tell of a solidarity pact made between twenty prominent artists, physicians, lawyers, political activists, and communal leaders—including Rabbi Shapira—not to leave the camp individually without safe passage of the entire group. In honoring this pact, he apparently passed on an opportunity to escape the labor camp in the summer of 1943. His martyrdom would come a few months later in early November, when Waffen SS units surrounded the camp and shot all the inhabitants.

After the war, a Polish construction worker unearthed the Piaseczner’s writings together with a note requesting that they be sent to his brother in Israel. One of the resultant books, Eish Kodesh, published in English as Sacred Fire, is a collection of deep theological meditations on the problem of evil by way of commentary on the weekly parsha. It was the last piece of Jewish scholarship written in Poland.

Chovas HaTalmidim, rendered in this new translation as “The Students’ Obligation,” is the Piaseczner’s educational manifesto and the only work published during his lifetime. When it appeared in 1932, Hillel Zeitlin, the great Hebrew and Yiddish essayist, wrote a celebratory review calling it a “gateway for anyone, and in particular for the modern Jew who has felt a genuine calling to return to his tradition, to enter the palace of Hasidism.” Shapira’s goal was actually two-fold: to dissuade Polish Hasidic youth from defecting to the secularist—socialist, Zionist, and Yiddishist—forces then laying siege to the traditional life of faith, and to cultivate an elite cadre of spiritual seekers (bnei aliya) who would infuse the traditional world with renewed religious energy.

In his posthumously published Hakhsharat HaAvrekhim (The Young Men’s Preparation), a sort of sequel to Chovas HaTalmidim, Rabbi Shapira wrote that his goal, and really the ultimate goal of any form of religious education, was to “uncover one’s soul,” to “grab one’s soul by the scruff of its neck,” and force it into an encounter with reality. By first sensitizing the individual student to the holiness within him or her—through imagination, song, and spiritual fellowship—the sanctity of the Torah and the living tradition of holy texts and personalities would eventually be grasped and understood.

The Piaseczner’s teachings on childhood steer a middle course between a Rousseauian celebration of childhood and a more classical positioning of the child as a kind of incomplete adult. He begins the book by arguing that habituation and socialization, the hallmarks of a classical education whether sacred or secular, were no longer sufficient. Children were maturing faster than ever; were more likely to become alienated from parents, culture, and tradition; and were increasingly robbed of the kind of personal investment that fosters lasting meaning and commitment. He reads, sometimes, like a Hasidic Neil Postman.

Repeatedly, Rabbi Shapira points to the spiritual force latent in the young student’s soul and the duty of teachers to develop it.

Since a Jewish child has the spirit of God, the breath of the Lord, hidden and concealed within him from the moment of birth, it is necessary to raise and educate him to bring out and reveal this godliness and allow it to flourish.

In Eish Kodesh, Shapira expands on a suggestive kabbalistic image from Tikkunei HaZohar that identifies schoolchildren with “the face of the Divine Presence” (Anpei de-Shekhina).

This might be instructively contrasted with another theological account of the child, one made famous by St. Thérèse of Lisieux. St. Thérèse (1873-1897), a Carmelite nun whose Story of a Soul has influenced readers from Jack Kerouac to the present pope, was inspired by the Gospel’s insistence that “unless you be converted and become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven”(Matthew 18:3). For Thérèse, spiritual childhood is a form of consciousness acquired when complexity of thought and calculation are abandoned: “It is enough to acknowledge one’s nothingness and surrender oneself like a child into God’s arms . . . I rejoice in my littleness because ‘only little children and those who are like them shall be admitted to the Heavenly Banquet.’” In contrast, Shapira invokes the image of “the face of the Divine” to stress the creativity and spiritual dynamism inherent in the youthful soul.

Rabbi Shapira teaches that the child is the most potent expression of the possible. The pupil occupies a space between what is dynamic and changing and what is eternal. In this way, the child is an apt symbol for the meeting point of the divine and the human, the “face of the Shekhina.” The intensity and immediacy of our childhood experiences express this continuous connection to the divine, which is precisely why they are capable of leaving such a lasting impression on us.

By developing a distinctive personality and calling, every human being can instantiate the Anpei de-Shekhina, that quality of the divine that is most identifiable and accessible in this material world and is most powerfully embodied in the person of the young. It is the main task of the parent or educator to tap into the particular spiritual excellence of the individual child, cultivating her distinctive qualities and drawing them up from the realm of the potential into the realm of the actual.

These student-centered ideas have been enthusiastically embraced by many in today’s Jewish world. In some neo-Hasidic circles, however, the Piaseczner’s insistence on the concrete demands and commitments of God-given law has been bypassed in favor of meditation upon the autonomous self. This was not Rabbi Shapira’s intention: “in writing this book, we have no intention of releasing you from the obligation and necessity of poring over the Talmud, Midrash, Shulchan Arukh, and all the other holy books that guide us upward on the path to God.” Shapira’s great pedagogical insight is precisely that one could adapt to the child without forsaking tradition. Indeed, both the pupil and the tradition require just such an approach.

We must adjust ourselves to [the student], and speak in a language that he can understand—almost to the extent of becoming children ourselves . . . It is not enough to merely teach the youth that they are duty-bound to listen to their teachers . . . the most important thing is to teach them that they themselves are their own educators. They are seedlings that Hashem has planted in the vineyard of Klal Yisrael, and they alone bear the responsibility for their development into towering atzei chayim, trees of life—righteous and deeply learned servants of Hashem.

For the Piaseczner, while each single student has a distinctive essence waiting to be realized, the refinement of mind, will, and character necessary for that realization lies within the traditional teachings of the Torah and in apprenticeship to its demands.

This is the second English-language translation of Rabbi Shapira’s educational treatise to appear in the past twenty years. Accompanying it is a biographical sketch by Aharon Sorasky, originally written in Hebrew and appended to most editions of the book, which betrays the influence of standard Hasidic hagiography:

When the child was two, he suddenly became seriously ill. Hasidic elders relate many miracles which took place during those days. As a segulah (mystical remedy) against the convulsions, his father requested that some of the child’s fingers be bound together with the leaves of his lulav, which he had set aside to be used for baking matzos.

Nevertheless, it manages to convey something of the genuine holiness and deep human wisdom of the Piaseczner’s personality. As for the translation itself, it betrays its origins in the work of a committee commissioned by Feldheim Publishers. Unlike the earlier rendering by Micha Odenheimer, published in 1995 and still in print, it substitutes a certain stylistic flatness for the author’s often finely worked turns of phrase and suggestive plays on words. For instance, the Feldheim translation has the author ask:

But what are we supposed to do in our generation where children’s independence and emotions develop far before their time? . . . then that enthusiasm will find its outlet elsewhere—in the false beauty and decadent culture of the secular world.

Odenheimer renders the same passage as follows:

But what choice do we have in our generation, when feelings and sense of self develop so precociously? . . . [our young people] will be moved and excited by foolish stimulants, by the base beauty that is found in the world.

In a few cases, entire passages have been either removed or condensed, one suspects out of a paternalistic intention to shield the uninitiated from the more mystically recondite elements of Rabbi Shapira’s thought.

Still, the benefits of this edition—it is handsomely produced and bilingual, with the English translation facing the Hebrew original—should not be overlooked, aiding both newcomers and seasoned students in the study of a seminal work of pedagogy and theology.

We may well wait in vain in this new century for a transformative figure of Rabbi Shapira’s stature to appear again. In the meantime, one can encourage educational traditionalists and progressives alike—in fact anyone who has, in Hillel Zeitlin’s words, “felt a genuine calling to return”—to read and think about The Students’ Obligation.

Suggested Reading

Letters, Summer 2022

Orthodox Lens; Kafka's Gimel; True Crime or Conspiracy Theory?; Of Censorship and Naughty Boys, and more

Golden Books

Three decades ago, Allan Nadler went to Vilna to reclaim books that the Nazis had plundered from YIVO, or so he thought. Dan Rabinowitz’s Lost Library solves the mystery—and raises important questions.

Write a Modern Letter, Live a Modern Life

Imagine that you’re a woman living in a shtetl in 1900: what do you say in a letter to your husband in America if you think he’s cheating on you?

The Other Bernstein

Late August 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth and the first Yahrzeit of his brother, Burton, who wrote an incredible family memoir.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In