Golden Books

The recent news that the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research—home to the world’s largest and most important collection of Yiddish books—summarily fired all its librarians including its head librarian and one-time chief archivist, Lyudmila Sholokhov, in a single day shocked students, scholars, and lovers of Yiddish. YIVO’s librarians have guided thousands of researchers of Eastern European Jewish history, languages, and culture for almost a century. Within 36 hours, a petition denouncing the action had already been signed by more than one thousand academics, authors, public intellectuals, and former employees of YIVO.

Resignations from YIVO’s Board of Trustees and obfuscatory press releases followed. Meanwhile, its Winter/Spring 2020 newsletter carried the headline “500 Books from Chaim Grade’s Personal Collection Added to YIVO’s Library Catalog.” The article announced the establishment of the “Chaim Grade Memorial Library,” with an accompanying photo of a few books on a bookshelf. Readers who remembered that YIVO had won a protracted legal battle with Harvard and the National Library of Israel for the great Yiddish novelist’s library seven years ago might have wondered about Grade’s other 19,500 volumes and why YIVO chose to illustrate the news with four battered volumes of Goethe and one of Robert Wistrich’s many histories of antisemitism (currently available on Amazon for around $14). Grade was perhaps the most erudite Yiddish writer of the 20th century, so why use a picture of books one could pick up at an estate sale on the Upper West Side on any given Sunday? More pressingly, who will catalog the rest of them?

Since its 1925 founding in Vilna (then Wilno, Poland; today Vilnius, Lithuania) to the present—and despite the destruction of its headquarters by the Nazis in 1941 and its displacement to New York City—YIVO has been the world’s premier center for academic research in every aspect of Yiddish studies. YIVO’s almost half a million books, along with the researchers who need to consult them, are today suddenly sheep without a shepherd.

The most treasured part of YIVO’s present-day library—named the Vilna Collection—consists, quite literally, of Holocaust survivors. These books and manuscripts are the most valuable bibliographic remnants of the vanished civilization of Eastern European Jewry. They were salvaged from destruction and shipped to Frankfurt by their Nazi plunderers for preservation in Hitler’s planned Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question. While many of these salvaged books belonged to YIVO’s prewar library in Vilna, the lion’s share had been looted from Vilna’s Strashun Library—the world’s richest and most celebrated prewar Jewish public library. As Dan Rabinowitz’s new and remarkable history of that “lost library” documents, the manner in which YIVO attained ownership in 1947 of some 27,000 Strashun Library books, including many from the personal library of its founder, Mattityahu Strashun, is a fascinating and ultimately inspiring (if not entirely legal) story.

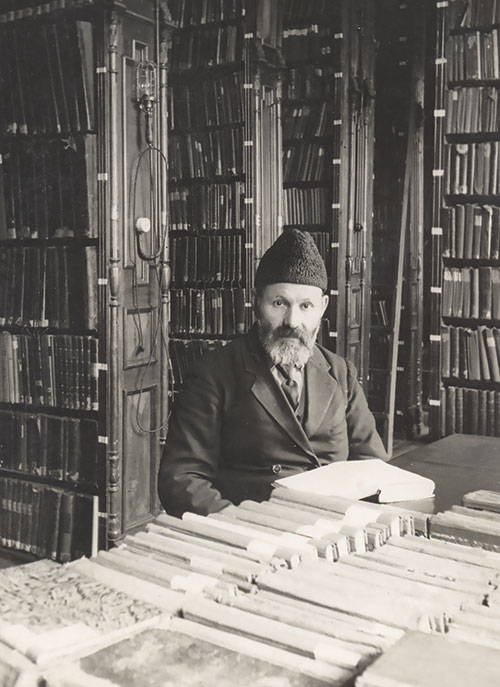

Di Strashun Bibliotek, as it was known in Yiddish, had been by far the most accessible of all the world’s prewar Jewish research libraries. Its genuinely fabled reading room was a haven of Jewish intellectual pluralism. Pious rabbis were commonly seated alongside young, secular, bareheaded male and female readers on the benches flanking the reading room’s perennially crammed tables.

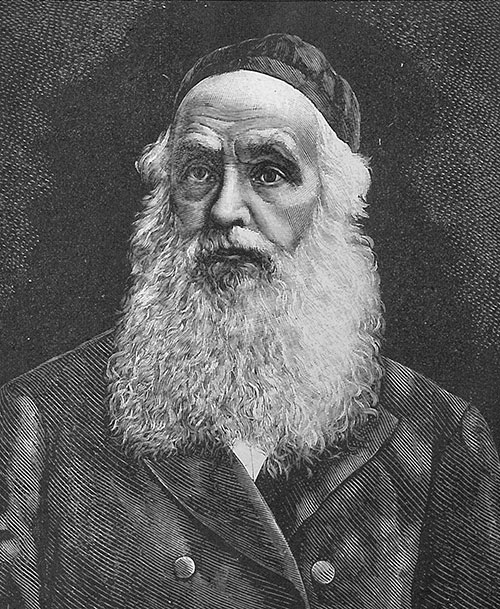

The core of the Strashun Library consisted of rabbinic tomes and Hebrew literature, from medieval to modern (although it included books in a dozen or so languages, the percentage of Yiddish books in its collection was surprisingly small). Head librarian Khaykl Lunski, a bearded, pious, yet thoroughly ecumenical Jew, wasalways standing on duty—even on Shabbat, after shul (the library was open, but pens and pencils were banned)—to help his patrons.

The library was housed in the old Jewish neighborhood known as Der Shulhoyf(Grade’s classic book of that name lovingly describes this intensely Jewish enclave, including the library and its patrons). YIVO’s spanking new Vilna headquarters, by contrast, was constructed in 1925 in a modern part of town beyond the Shulhoyf, where both Jews and Polish Catholics lived. Everything about YIVO was modern, a break from the sequestered and rabbinically dominated past, as well as from the elitism of 19th-century German Wissenschaft des Judentums (Science of Judaism), which had been dominated by rarefied textual studies that ignored folk culture and the socioeconomic history of the Jews. (The V of YIVO’s acronym is for the Yiddish word Vissenshaft, but as Max Weinreich quipped, this was vissen vos shaft—i.e., knowledge you could make something out of, not the airy concerns of historians of ideas.)

YIVO was founded to pioneer in the modern study of the Jewish masses and their folklore, culture, music, psychology, and history. Its founders had little interest in the rabbinic books that formed the core of the Strashun Library. While both flourished in Vilna,the two libraries operated independently of one another until their respective destructions by the Nazis. There is no evidence that the two libraries ever had even so much as an interlibrary loan arrangement, let alone any deeper form of association.

So how did YIVO end up inheriting close to 30,000 surviving books from the Strashun Library? As the prolific Hebrew and Yiddish author and director of the (now defunct) Central Rabbinical Library at Heichal Shlomo in Jerusalem, Tzvi Harkavy, declared in exasperation, “What do [secular] Yiddishists in New York have to do with a rabbinic library that [Rabbi] Mattityahu Strashun bequeathed to the Vilna community?” To YIVO’s immense discomfort, Harkavy also happened to be Strashun’s great-nephew and lobbied, without success, for the books’ “return” to Heichal Shlomo’s library, which in the end received only duplicates from YIVO’s Vilna Collection, despite the full support of Israel’s Ministry of Religious Affairs, as well as that of every member of the Israeli Association of Jews from Vilna. The final chapter of The Lost Library, aptly titled “Another Port of Call,” for the first time recounts the full history of YIVO’s stubborn contention with the Jewish state’s claims on the Strashun books. In 1956, Israel’s deputy minister of religion, Knesset member Rabbi Zerach Warhaftig, sent an official letter to YIVO demanding the “repatriation” of the Strashun books to Israel. Three years later, Jerusalem’s Supreme Rabbinical Court ruled that “Harkavy was the sole [living] heir to the Strashun Library,” but, supreme or not, a beit din in Israel had no standing in America, and the ruling was easily ignored by YIVO. Had Israel become a nation-state a year earlier, countless treasures, including the Strashun books, might have been returned to it by the Americans.

In my decade as YIVO’s director of research, which included oversight of the library, I can say that almost no one ever came to YIVO in search of biblical, talmudic, or medieval sacred texts, all of which could be found in greater abundance at the New York Public Library, as well as at the libraries of the Jewish Theological Seminary, Yeshiva University, and Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. So, to repeat, how and why did YIVO end up with the Strashun collection? The complex, hitherto murky, and too often deliberately distorted story of the postwar destiny of this greatest of all Jewish public libraries has finally and definitively been recounted in Rabinowitz’s superb study.

When Napoleon Bonaparte entered Vilna’s fabled Shulhoyf and gazed at the magnificence of the Great Synagogue’s sanctuary, he declared, “This is the Jerusalem of the North!” Whether this story is true or not, Jewish Vilna flourished over the next century and a half. It was Eastern Europe’s most distinguished center of rabbinic scholarship, but it was also the first and most vibrant center of Jewish modernity, a major hub of the Hebrew Haskalah and its 20th-century cultural and political offshoots. The first modern Hebrew poet, Judah Leib Gordon, came from Vilna, as did the first Hebrew novelist, Abraham Mapu. The city was the major Eastern European center for Zionism and Hebraism, as well as the birthplace of both the Yiddishist Jewish Labor Bundand, of course, YIVO.

All of this was destroyed when the Nazis and their enthusiastic Lithuanian collaborators exterminated 90 percent of the Vilna province’s Jews in the Ponar forest. But the Nazis deemed some of their books worthy of preservation—including thousands of volumes from Rabbi Strashun’s original collection—and shipped them to Frankfurt, ultimately to be stored in a massive warehouse in nearby Offenbach, where after the war they were meticulously arranged according to their owners’ places of origin. So it was that the crates of YIVO’s and Strashun’s collections were assembled adjacent to one another on the ground floor of the Offenbach Archival Depot (OAD).

It was only when the Frankfurt area fell within Germany’s American zone that the now-celebrated “monuments men” found the massive crates containing the surviving collections of both the YIVO and Strashun libraries. With the appointment of US Colonel Seymour Pomrenze—whose brother was a prominent member of YIVO’s board—followed by the more learned and meticulous bibliographer Isaac Bencowitz to supervise the allocation of these riches, the distinction between these libraries became increasingly fuzzy. With the 1946 arrival at Offenbach of historian Lucy Schildkret (later Dawidowicz), who was, at the time, YIVO director Max Weinreich’s closest student, three entirely invented new accounts of the previously nonexistent YIVO-Strashun “relationship” emerged. In his meticulous account of this revisionism, Rabinowitz shows that Weinreich, Pomrenze (who stuck to YIVO board chair Marcus Julius Uveeler’s version), and Dawidowicz each had their own fable about the merging of the YIVO and Strashun libraries, from a fictional Soviet “superlibrary” that submerged them both before the Nazi takeover to an imagined entity known as the Associated (Vilna Jewish) Libraries, to an apocryphal account according to which the directors of the Strashun Library begged YIVO to take possession of its books shortly after the war’s outbreak. All historical nonsense, but nonsense for the sake of scholarship, and arguably also for the sake of heaven, since clear title was an impossibility and the precious books had to go somewhere.

New York.)

While Rabinowitz scrupulously avoids sensationalism, his documentation of the manner in which Dawidowicz ultimately managed to manipulate US Captain Joseph Horne, the director-general of the OAD, suggests that there was a romantic element to her success in winning him over. Thus, in a series of strictly confidential letters to Weinreich from February to May 1947, she described Horne as a “very weak and an emotional person . . . too scared to be dishonest and too intelligent to want to take a risk . . . afraid for his job, because life was never so good for him back home.” In a later letter, Dawidowicz went further, boasting that her “personal relationship with Horne” had given her “knowledge not only of him, but of the Depot to the extent that no other person presently in Germany has.” Despite expressing a small measure of discomfort with the particular advantage she employed in winning Horne’s heart for her as well as for YIVO—she candidly admitted that “sometimes I think it sort of unfair to capitalize on it”—in the end, Dawidowicz coldly concluded that “business is business, and I [am] far more interested in the disposition of Jewish books than in the disposition of Horne.”

Rabinowitz’s account of these machinations, which at times reads like a spy novel, finally explains a puzzling experience I had when I worked at YIVO. In 1989, YIVO’s leaders discovered that another 40,000 Strashun/YIVO books were in the basement of a former church after the Soviet annexation of Lithuania. They were lying in unsorted piles three years later when I arrived in Vilnius to try to recover them along with important archival papers.

Even four years after Lithuania’s liberation from Soviet rule, a historically justified paranoia still weighed on those very few librarians who had been aware of these books’ existence all along. Under cover of night, I was furtively escorted into the National Library of Lithuania’s so-called Jewish Book Chamber in that church basement by the late Fira Bramson, a survivor of the mass execution of the Jews of her native Kaunas (Kovno in Yiddish) and the only competent Judaica cataloger in the country. There, I found dozens of holy scrolls, Sifrei Torah among them, lying naked in rows on industrial steel-gray warehouse shelving, and innumerable massive piles of randomly stacked Jewish books, which my predecessors and colleagues at YIVO led me to believe rightfully belonged to us. But when I opened some of these books, I was surprised.

Since my appointment at YIVO two years earlier, I had spent countless hours wandering through the massive creaking old wooden stacks of its library. I had familiarized myself with its Vilna Collection, namely the prewar library that had been “repatriated” to the institute in 1947. Well over half the books bore the distinctive ex librisstamps of both YIVO’s prewar Vilna Library and the Strashun Library.

Now I was in Vilna examining what was left behind of the very same Strashun Library, and I was puzzled by the absence of so much as a single YIVO ex libris among those massive piles of books. Yet, I set the question aside and went about my urgent business, demanding the “return” of YIVO’s books. I considered this a moral mission: reclaiming plundered Jewish property for the Jews. I still do, but upon reading The Lost Library, the scales fell from my eyes.

For, as Rabinowitz reveals, on the very same day, June 17, 1947, that the massive shipment from Offenbach—270 shipping crates containing more than 32,000 books—finally left Germany for New York, Dawidowicz wrote yet another strictly confidential letter to Weinreich. In the envelope was a page that reproduced several samples of the prewar ex libris from the Vilna YIVO Library. The message in her letter was an urgent, cryptic, but not terribly subtle directive to Weinreich: “[G]et a couple of stamps made [in New York] and start stamping.”

Weinreich surely understood the urgency of Dawidowicz’s advice. YIVO was about to receive what Dawidowicz and Weinreich had successfully argued were the remains of its prewar library; to prove its claim, it was imperative that YIVO imprint these faux prewar ex libris onto the pages of all the books that, as both Dawidowicz and Weinreich knew perfectly well, had previously belonged solely to the Strashun Library, not YIVO. They constituted over 75 percent of the volumes in those crates. The reason there were no YIVO stamps on the books I saw in Vilnius is that they had never been YIVO’s in the first place.

It is unsurprising then that the anniversary of YIVO’s acquisition of the lost Strashun Library was never celebrated. In fact, the acquisition was kept virtually secret for the next 16 years, the books having been assimilated into a new collection that the institute claimed was from its (fictional prewar) Vilna Collection. The name “Strashun” would not be uttered at YIVO or mentioned in its newsletter, Yedies fun YIVO, until 1963. What Rabinowitz laments is that, to this day, YIVO insists on falsifying history by sticking strictly to the simply untrue stories it had deemed necessary in 1947 to salvage the Strashun books for

the Jews.

Rabinowitz is at pains to document this preposterous and unnecessary commitment to revisionist history. He quotes the anachronistic account of the Strashun Library’s history in a booklet distributed at a 2001 exhibition of YIVO’s Vilna treasures, Mattityahu Strashun (1817–1885): Scholar, Leader, and Book Collector. He also calls attention to the 2013 visit to Vilnius of YIVO’s executive director Jonathan Brent—one of many, perhaps too many, such trips—after which he published an article asserting the historically false claim that “[a]ccording to oral accounts from that confused time, [the Strashun Library] was put into the safekeeping of the YIVO Institute.” As a skilled historian of Stalinism, it is hard to imagine that Brent is unaware of the unreliability of oral accounts by unnamed sources. And yet, as recently as 2017, at a YIVO conference titled “The History and Future of the Strashun Library,” the actual history of how its bibliographic treasures became YIVO’s property was entirely elided, and the conference program’s historical preface once again toed YIVO’s implausible party line.Rabinowitz’s meticulous documentation clearly lays out the bottom line: Only 61 crates containing 8,842 books were, in fact, from YIVO’s prewar library in Vilna. The remaining 209 crates contained 23,709 books from the Strashun Library.

YIVO’s ultimate success in rescuing these books resulted in a far-from-unhappy outcome, and its leaders, especially Weinreich and Dawidowicz, must, in the end, be celebrated as heroic figures who did everything they could to return Jewish cultural treasures to their people. As even Rabinowitz ultimately avers, the successful, if less than scrupulously honest, methods employed by Weinreich and Dawidowicz resulted in the rescue of the Strashun Library’s treasures. Had they not acted as they did, the books likely would have been returned to Poland or, theoretically, the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. But Jewish survivors who returned to Poland were themselves being murdered by Poles, as Rabinowitz sharply notes. “Restitution” to Lithuania was no more tenable.

Despite Rabinowitz’s often aggressively legalistic pursuit of the less than honest tactics and false historical narratives employed by Weinreich, Dawidowicz, Pomrenze, and Bencowitz to secure Strashun’s books, nothing he documented can reasonably be viewed as impugning the nobility of their goals or the moral necessity, given the extreme situation in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, of lying for the sake of a higher purpose. I am aware of no religious argument that would trump the halakhic mandate to violate the law in times of such extreme distress, or for that matter, the Polish Jesuit doctrine of “mental reservation” that allows for necessary untruthfulness in the pursuit of higher goals. Nor can I imagine a moral argument that would condemn what Weinreich (whose reputation for impeccable integrity equaled his unmatched scholarly greatness) and his collaborators felt the need to do to: save these sad but sacred remnants of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. In Jewish law and lore, books—especially sacred ones of the type that filled the Strashun Library—attain the closest status to human life. Although not a religious Jew, Weinreich was versed in “the ways of the Talmud” (derekh ha-Shas) and almost certainly perceived his rescue of as many Jewish books as possible as a belated act of pikuach nefesh (the saving of souls). None of this, however, quite answers the claims of Tzvi Harkavy, Heichal Shlomo, and the Israeli government after the books had been saved.

Nor can one defend the continued distortions of the historical record by today’s YIVO. The moral low may have come under its previous executive director, Carl Rheins, who arranged for some of the Strashun Library’s rarest books, including many that were part of Mattityahu Strashun’s personal collection, to be auctioned off. The sale did not solve YIVO’s financial problems. Then, as now, YIVO’s most important resources (books then, their caretakers now) were given up to temporarily offset budgetary deficits.

Among Strashun’s treasures that perished in the Gestapo’s flames was a visitor’s log, named Sefer ha-zahav. However, in 1939, the library’s director, Khaykl Lunski, published an article about this “golden book,” which had been conceived for Theodor Herzl’s visit in 1903. While Herzl never made it to the Strashun Library, the Sefer ha-zahav was over the subsequent years signed by hundreds of leading figures of the pre-Holocaust Jewish world, some of whose inscriptions were transcribed by Lunski. The leading prestate Zionist historian of the Jews, Ben-Zion Dinur, was stunned by the ecumenical spirit of Strashun’s reading room and wrote:

“[T]here is no other Jewish community with [as much] Jewish unity as in Vilna, and especially so in theinstitution of Jewish unity, the Strashun Library” . . . where inside there “were long tables, [. . .] and chairs and benches one next to another, where a large crowd was sitting; in total silence, not a sound was heard. Rabbis and old Talmudic scholars were studying . . . and next to them the younger generation . . . were swallowing Haskalah literature with gusto.”

Other inscribers included the greatest Jewish writers, scholars, and thinkers of the age: Chaim Nachman Bialik, Mendele Mokher Seforim, and Hermann Cohen, among many others, including the great historian Simon Dubnow, who wrote that this “Hebrew and Jewish library will become a spiritual center for all those seeking knowledge.” But it was not only Jewish modernists who wrote in the golden book. Lunski’s article includes similarly ecstatic comments from some of the leading rabbis of Eastern Europe, such as Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, Vilna’s chief rabbi and the world’s leading halakhic authority, and the towering moralist Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan, known as the Chofetz Chaim.

Unsurprisingly, it was Sholem Aleichem, the most beloved of all Yiddish writers, who captured the uniqueness of the Strashun reading room most whimsically:

I have never seen such a Jewish treasure house as this library, neither in real life nor even in a dream, during which fantasy seizes the author and carries him on wings far, far away from reality.

The luxury of being transported far from reality belongs to novelists and poets, prophets, dreamers and madmen, but certainly not to research institutes whose missions demand strict fidelity to history. As Rabinowitz soberly concludes:

Many institutions have disclosed their historical collection methods and begun a necessary dialogue regarding the complexities of the confluence of war, lawlessness, looting, and the responses of institutions tasked with preservation of the historical . . . record. The complete story of the Strashun Library, and specifically the methods that resulted in transferring it to New York . . . and the fate of many of its books in the years that followed, have yet to be reckoned with.

Indeed!

Suggested Reading

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

Vegetarian in Vilna

The long, brutal winters and meaty cuisine of Eastern Europe don’t immediately make one think of garden-fresh vegetarian recipes.

No Empty Place

The most substantial theoretical response to Hasidism from a leader of the mitnagdic—literally, opposition—movement did not appear until 1824, three years after the passing of its author, Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In