Brave New Bavli: Talmud in the Age of the iPad

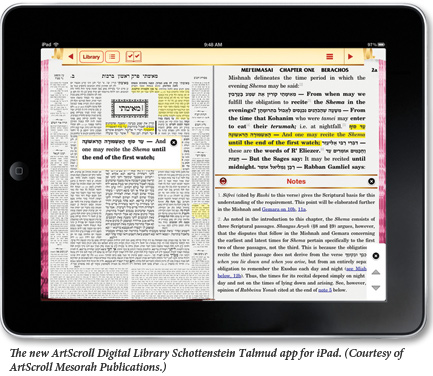

A promotional video distributed by Logos Bible Software shows contemporary Christians taking their iPads to the local coffee shop to read and annotate virtual bibles illuminated by stunning images and commentary. In a sufficiently cosmopolitan cafe, another patron might be reading the Quran using myQuran HD. And now, to complete the scene, it is possible to study the Talmud with a user-friendly iPad application. The formidable Orthodox publishing house ArtScroll Mesorah has come out with its new ArtScroll Digital Library Schottenstein Talmud. (The rival app from Koren, part of the ongoing Steinsaltz Talmud project, was not released in time for this review).

The Babylonian Talmud (the Bavli, as it is referred to in Hebrew) is a sprawling multi-volume compendium of rigorous legal argument, ingenious and fanciful biblical interpretation, legends, anecdotes, historical narrative, plainspoken advice, and deep moral-theological investigations, all intertwined. Compiled between 200 and 600 C.E., it has been the book for the People of the Book. On the other hand, the Bavli isn’t really a self-contained book, or even a set of books at all. If any religious classic has been hypertextual all along it is the Talmud, with its non-linear arguments, gleeful digression, incessant citation, and endless commentary.

The commentaries, glosses, and indices that have come to surround the main text on the standard page might be thought of as the Bavli’s historical attempt to strain against the limitations imposed by print. But today, the technology to free the Talmud from its paper prison actually exists, and it is alternately fascinating and frustrating to see how ArtScroll has approached the challenge.

The history of talmudic reading and scholarship illustrates at least part of Walter Benjamin’s famous argument in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” For both the Talmud’s meaning and the nature of its authority have changed with the ways in which it has been preserved and reproduced.

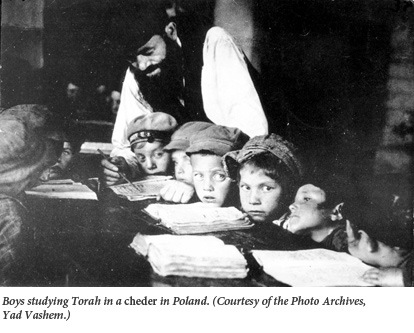

The great rabbinic works of the first centuries C.E., the Mishnah and the Bavli, were “published” as oral texts, that is, highly organized compilations that were first encountered through the recitation of a teacher who had already committed the text to memory, and subsequently repeated and reviewed by the disciple until he too had assimilated it. The centrality of the master-disciple relationship to this process reinforced a core doctrine of rabbinic Judaism: that the Oral Torah was the product of an uninterrupted chain of teachers and students reaching back to Moses himself, the recipient of the Written Torah, or scripture.

The geonim—the heads of Babylonian talmudic academies during the post-talmudic era (roughly 600–1000 C.E.)—established the Bavli as the authoritative corpus of Jewish law. Although the Bavli was put into writing during this era, the geonim continued to claim that an expert reciter’s readings were more authoritative than those of a handwritten manuscript. However, as Jewish communities spread across North Africa and Iberia in the wake of the Muslim conquests, they required guidance from afar. That is, they needed texts.

From Baghdad, then one of the largest and most powerful cities in the world, the geonim used the caravan routes to correspond with these increasingly far-flung communities. But this correspondence was, of course, written, and it soon formed the nuclei of nascent libraries. It was only a matter of time before local scholars, trained on manuscripts instead of oral pedagogy, displaced the distant geonim as authorities on Jewish law. In the history of talmudic scholarship, the high medieval period of the rishonim (early commentators) begins with this transition from oral to written instruction, and the consequent primacy of the manuscript.

The early modern period of rabbinic scholarship begins with Rabbi Joseph Karo’s 16th-century code of Jewish law, the Shulchan Arukh (the “Set Table”)—which is to say, more or less, that it begins with Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press. Or rather it begins when Rabbi Moshe Isserles realized that he could frame his own halakhic scholarship as an Ashkenazic supplement to Karo’s summation of Sephardic halakha, the “Table Cloth” for Karo’s set table. When the two were printed together to form the Shulchan Arukh as we know it, they summarized and sealed an era.

The legal authorities cited by Karo and Isserles became the rishonim, and they, together with all subsequent authorities, became the achronim (later commentators). After the 16th century, these achronim found themselves practicing a strong doctrine of legal precedent: It was almost impossible to disagree with a rishon without recourse to a supporting opinion from another rishon. In short, scholars whose works were published in movable type could not disagree with those whose works had circulated in manuscript.

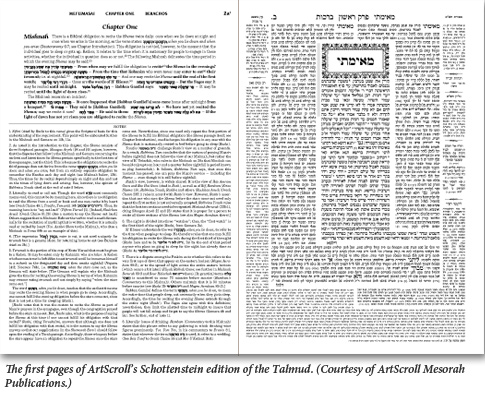

During this period, the Shulchan Arukh and the Talmud both took on their now-characteristic printed form: a central block of text framed by columns of commentary in smaller type. In the case of the Talmud, the first volume of which was printed in Italy by Joshua Solomon Soncino in 1483, the layout reached its more or less still-canonical form in the edition printed by the Romm family in Vilna at the end of the 19th century.

In his famous essay, Walter Benjamin wrote of the original artwork as having a kind of intrinsic value, even holiness—what he famously called an “aura”—because it bore the human mark of its maker. This was lost, he said, in the “age of mechanical reproduction.” There is an interesting anticipation of this idea in a legal ruling by another German-Jew, Rabbi Yair Bachrach, writing in the late 17th century. Bachrach was asked whether the prohibition against having sex in the presence of scripture applies to printed texts. He responded saying, “the sanctity of a Torah scroll stems from the writing of a man in whom there is a soul, a part of God above . . . if tefillin, mezuzot, or a Torah scroll would be printed, it is inconceivable that they would be valid.” Although it is specifically with regard to scripture, Bachrach’s responsum expresses the recognition that something had fundamentally changed with the advent of print.

It is also true, however, that the printed pages of the Vilna edition themselves achieved an iconic status within the traditional world of Jewish scholarship. Although endlessly reproducible, the Vilna page nonetheless possesses an aura even now. When, in the 1960s, the popular Israeli rabbinic scholar Adin Steinsaltz began publishing an edition of the Bavli with Hebrew translation and, among other innovations, a new layout that diverged from the Vilna, he was excommunicated by some outraged rabbinic authorities. One of the challenges ArtScroll faces is finding a way to exploit the possibilities of the new touchscreen medium while respecting the traditionalist sensibilities of its primary readers.

In this attempt, ArtScroll is building not only on its own enormously successful translation (on which, more in a moment) but on a generation of earlier digitizatations of rabbinic literature, the most important of which has been the Bar-Ilan Responsa project, a massive database of classic texts, on DVD. More recently, apps such as PowerSefer and OnYourWay (from Deuteronomy’s famous exhortation to study on the go, u-velekhtekha ba-derekh) have made an ever-increasing amount of this material accessible on tablets and smartphones. Such products offer the experienced scholar a rather large bookshelf of untranslated classic Hebrew texts. Having so much textual data at one’s fingertips has changed the nature of rabbinic study and research, but it hasn’t fundamentally altered the experience of reading the Talmud, or made it more accessible to a wider audience.

In 1923, after the devastation of Jewish communal life by World War I, a brilliant young Polish rabbi named Meir Shapiro made a bold suggestion: Jewish laymen all over the world ought to study the same daf—a folio page of Talmud—every day. Each page, he said, would ascend to heaven with the help of “hundreds of thousands” of learners, who would complete the entire Talmud together in seven and a half years. Over the last two decades, ArtScroll’s massive Talmud translation project made this book club on steroids a realistic aspiration for a broad range of American Jews for the first time. Without ArtScroll, the gathering of some 90,000 Jews last month to celebrate the completion of the daf yomi cycle at MetLife Stadium would be unthinkable.

The first volume of ArtScroll’s original print edition of the Talmud—named the “Schottenstein” after the principal benefactors of the project—appeared in 1990, and the series was completed in 2004. While the Talmud has seen a number of translations since the 19th century, one can argue that nothing comes close to the Schottenstein in terms of ambition or influence. Moreover, given the enormous difficulty of following the dense arguments and unexpected free-associations of the Talmud, the accessibility of the Schottenstein edition is an enormous accomplishment.

In the Schottenstein, cryptic rabbinic questions, answers, and statements are not merely translated. They are introduced, then quoted in the full Hebrew or Aramaic original, and only then translated, after which they are paraphrased in expanded form, explained, and then further explicated in long discursive footnotes, drawing upon traditional commentaries. ArtScroll describes this process and the resultant page as one of “elucidation” rather than translation.

Since this elucidation is significantly longer than (and, in fact, already includes the actual text of) the Hebrew/Aramaic original, each Vilna page ends up being reproduced two to five times for every English page (a grey bar shows the reader which segment of the Vilna corresponds to the facing elucidation). This decision, both brilliant and perverse, added well over 10,000 pages, bringing the entire series to 73 volumes. The perversity of adding 10,000 apparently superfluous pages is obvious, but the brilliance of the decision was that it always kept the “original” page before the reader. For those with enough background or intellectual stamina, this makes the ArtScroll translation an extraordinarily effective crib. For others, the page of the Vilna edition serves as a reassuring icon, preserving the aura of tradition, even as the translation has made the Talmud more accessible to its non-traditional readers (women, non-Orthodox Jews, and Gentiles).

Last February, ArtScroll showed a video at its annual dinner (later posted on YouTube, though it was recently removed) that announced the creation of an iPad app for the Schottenstein. With uncharacteristically arched brow, the video evoked the famous opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey—a Talmudic volume appeared rising above a lunar horizon as a deep-voiced narrator declared that the new app “will change everything.” Though the makers of the video were plainly thinking of Kubrick’s film, one wonders if they realized that the music was Richard Strauss’ Also Sprache Zarathustra, inspired by Nietzsche’s book, which infamously announced, in the name of the ancient founder of Zoroastrianism, the death of God and the rise of the Übermensch. Then again, maybe it was a nod to the context of late antique Zoroastrianism in which the rabbis of the Bavli lived.

What is it like to use the ArtScroll Digital Library app, at least right now? (As with any ambitious app, regular updates are promised.) When one opens it, a screen both reassures and admonishes its readers that “This app does not require connection to the Internet for daily use. Following the ruling of leading rabbinic authorities web devices should only be used with adequate filters.” Aesthetic choices also signal which part of the Orthodox community ArtScroll represents: the virtual bookshelf where Schottenstein volumes are stored is stained a deep brown, making it look like the seforim shrank of a Boro Park scholar rather than, say, the light-wood shelf on which one might place the novels of David Foster Wallace and Michael Chabon. There is even an option to frame the text with an image of the traditional speckled page edges. These cultural admonitions and traditionalist cues notwithstanding, it is an app.

At the top of the screen is an intuitive toolbar that allows one to navigate the text in several ways, a settings menu, and an icon that toggles between three main screen views: the Vilna page and the English page of elucidation side-by-side as in the original printed edition, the Vilna page alone, and the English page alone. The user can also employ a two-finger swipe to toggle between the two sides of the page (though in the present version there is a slight time delay).

In fact, part of the genius of the app is its sophisticated reinstatement of the Vilna page and its aura. Despite ArtScroll’s best efforts, not to speak of those 10,000 extra pages, the classic Vilna page has been largely ignored by readers of the Schottenstein, who spend most of their time on the (mostly) English page of elucidation. But nearly all of the app’s features—its pop-up windows, layout options, and highlighting capabilities—help the reader back to the Vilna page. Although it looks as if it was produced from the Romm family’s original plates, this is a Vilna page that comes to life with the tap of a finger. Depending on the options selected, touching a line of talmudic text opens a window that can show the reader the text vocalized, translated, further elucidated, or commented upon in significant depth.

Take, for instance, a famous passage from page 6a of Tractate Berakhot (Berachos in ArtScroll’s preferred Ashkenazic transliteration). R. Avin bar Rav Adda said in the name of R. Yitzchak: “From where is it derived that the Holy One, Blessed is He, dons tefillin? For it is stated: ‘Hashem has sworn by His right hand and by the arm of His strength.'” The note that pops up on these lines with a tap explains the extraordinary anthropomorphism of God putting on tefillin. The note invokes several commentaries but unfortunately, at least so far, does not offer the capability of viewing them in the original. Another pop-up helpfully informs us that the verse cited is from Isaiah 62:8 and even offers the option of viewing the entire verse. However, it does not (yet) offer the option of viewing the verse in its full biblical context.

In general, one can see that ArtScroll has only begun to exploit the great explanatory and expressive power that the app makes possible. Not only will one be able to swim in “the sea of Talmud” and its commentaries without ever either entering the Beit Midrash or leaving one’s seat (both of which are, arguably, losses), but the touchscreen app may actually be better suited to conveying the depth of the Talmud, with its bottomless commentary and endless allusions. ArtScroll says that future updates will provide hyperlinks to the original sources cited in the commentary, and between the commentaries of different tractates.

In the future, users may also be able to post insights or quotes directly from the app to Twitter or Facebook, but there will be no way to subscribe to or otherwise access the comments of others from within the app. In the words of ArtScroll CTO Mayer Pasternak, “Crowdsourcing presumes the democratization of information, and that is inconsistent on multiple levels with the ArtScroll Mesorah model.” This one-way social media model is understandable but it also makes one wonder whether ArtScroll can bring itself to fully exploit the new medium. Not only does the ArtScroll Mesorah model eschew crowdsourcing, it also does not seem to envision linking to a text that is not part of its limited rabbinic canon. (In the promotional video, we see a user writing, “Take a look at the ArtScroll Siddur commentary on Shema” with an as yet unreleased note-taking function.)

ArtScroll’s approach seems something like that of the company that created the iPad itself. Under Steve Jobs, Apple famously opted for creating a smooth, seamless experience at the cost of allowing users to exercise their own creativity with less finished systems and products. The experience of studying the Talmud with ArtScroll—print or app—is similarly smooth, with very few rough edges or loose ends. Like the device on which it runs, ArtScroll’s Digital Library was designed with consumption in mind, not production or innovation.

This is an extraordinary accomplishment, but the Talmud itself is not seamless or free of rough edges. Attempts to clarify the Talmud have always provoked new waves of commentary and dispute. Rashi’s monumental running commentary on the Bavli, still the greatest elucidation of the Talmud and the indispensable model for ArtScroll, made mastery of the Talmud much easier. In doing so, it opened the door for the more sophisticated analysis of the Tosafists, who made their living exploiting and reconciling precisely those loose ends and inconsistencies. What might the ArtScroll app provoke?

The spirit of the Mishnah used to appear to Rabbi Joseph Karo and he kept a journal of the visitations. Imagine that an incarnation of the Bavli were to design an app and attempt to replicate itself through this medium. What might it look like?

First of all, it would be a virtually borderless intertextual web. Talmudic passages that shed light upon one another would be linked in intricate overlapping networks. Passages citing earlier texts—biblical verses, the Mishnah, other rabbinic texts, the apocrypha—would be hyperlinked to the collection in which the cited text originally appears. Passages would also link to later commentaries, super-commentaries, relevant excerpts from legal codes and responsa, manuscript variants, monographs, homiletic interpretations, and, indeed, translations and elucidations. Discussions of Akkadian medicine would call forth images of Babylonian tablets. People, places, historical events, concepts, practices, and all sorts of other realia mentioned in the text would link to relevant explanatory pages, pictures, recordings, and video clips.

As for social media, when a reader opens a text, he or she would be able to see how many others are currently viewing that page, including how many friends. It would be easy to interact with them over the page, either in an open comment stream or in private “chat rooms” for classic two-partner chavruta study. Moreover, this community would include not only rabbis and laypeople but also linguists, historians, philosophers, literary critics, and other interested scholars.

This is a dream. There is really nothing like it out there for any form of literature, religious or secular. Still, there are apps that are on the right track. Perhaps the most celebrated and applicable is Touch Press’ Wasteland app, a gorgeous piece of technology in which T.S. Eliot’s poem is “surrounded” by early manuscripts and recordings of the poem, commentaries, and stages readings. Another literary app that allows users to create and publicly share their commentaries has been created for Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. And two new Jewish text websites, themercava.com and sefaria.org, offer promising platforms for crowd-sourced translation, commentary, and discussion of the Bavli and other Jewish texts. Perhaps most suggestively, the Brookings Institution recently launched a website called ConText to crowdsource commentary—popular and scholarly alike—to be placed in the margins of the U.S. Constitution. The inspiration for the project is, of course, the Babylonian Talmud.

The digital Talmud may have found its Rashi in ArtScroll’s new app, but it still awaits its Tosafists. That will change everything.

Suggested Reading

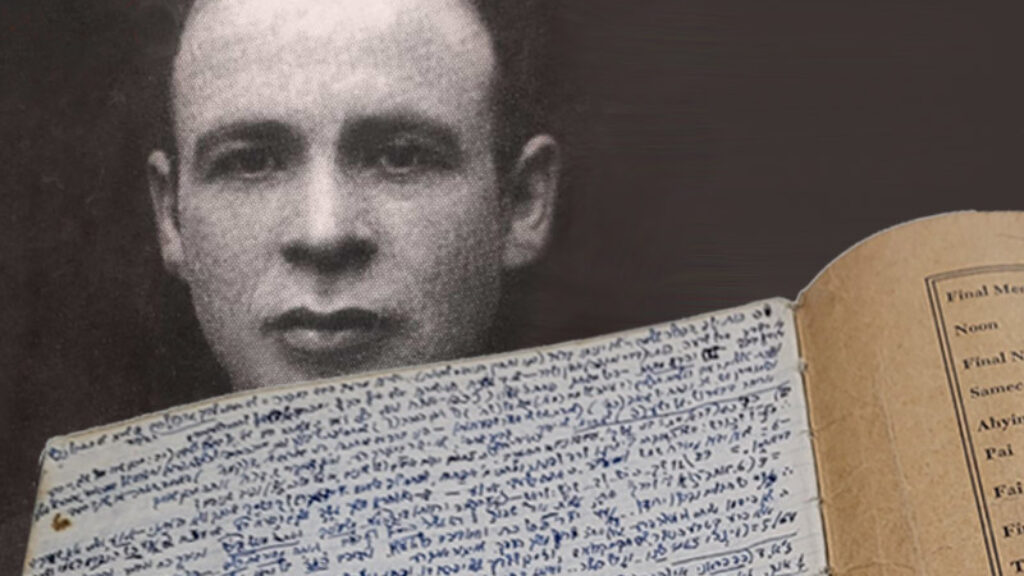

Think Over My Lesson and Try to Destroy It

When Levinas met a vagabond called Chouchani, he told a friend, “I cannot tell what he knows, all I can say is that all that I know, he knows.” Now that we have dozens of Chouchani’s notebooks, can we finally know what he knew?

Silence of the Lambs

Sacrifice is both foreign and familiar. Actually sacrificing an animal is difficult to imagine, and yet we continue to speak freely of sacrifice in connection with political and moral obligations.

An Exceptional Minority?

Response #1: Jack Wertheimer argues that Jewish assimilation is not an inexorable process.

Atlas Schlepped

Ayn Rand imagined that her romantic prose soared, but it barely schlepped along.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In