An Exceptional Minority?

A prominent sociologist of liberal Protestantism once asked me to organize an informal meeting with my Jewish Theological Seminary colleagues so that she could learn how Jews manage to retain their commitment to Judaism while being open to everything American society offers. Our response was a collective “if only.” I’ve had similar conversations with South Korean, Bosnian Muslim, and Latino students over the years, who see Jews as a model minority that has somehow managed to maintain its distinctive culture in American society.

These encounters came to mind while I was reading Allan Arkush’s trenchant, deeply felt essay “In the Melting Pot.” Revisiting a century of Jewish conversation about the possibilities for group survival on these shores, Arkush soberly concludes that like so many others who have leaped into the great melting pot of American society, most Jews in this country will shed their distinctive identity, if they have not already. Contrary to the perceptions of outside observers, they are not all that different from other ethnic groups; they too will likely assimilate, with only the Orthodox, especially the so-called ultra-Orthodox or haredi sectors, surviving intact.

Arkush’s overall analysis of the powerful pull toward assimilation can be augmented by data on what sociologist Richard Alba already in 1985 described as “the twilight of ethnicity.” More recently, Herbert Gans has written about “terminal ethnic identity” among whites of European background. Given these broad social patterns among whites of European background, why should Jews be any different? Why should they avoid the fate of so many other fourth- and fifth-generation Americans whose connection to the culture of their immigrant forebears is tenuous, if it has not disappeared entirely?

The only possible reason, as Arkush recognizes, is that Jewishness is not solely a matter of ethnicity or peoplehood but also entails religious commitments. Generously drawing upon my book The New American Judaism: How Jews Practice Their Religion Today, Arkush examines the health of various Jewish religious movements and nondenominational expressions of Judaism, noting declining levels of participation among the non-Orthodox while also acknowledging “signs of vitality.” Concurring with my assessment that “aside from anti-Semitic persecution, nothing is likely to play a larger role in determining the future of Jewish life in this country than the lived religion of ordinary Jews,” Arkush ultimately remains skeptical about “the long-term survivability of any form of Judaism in our modern liberal democracy that isn’t rooted in solid convictions and consolidated by a disciplined and more or less segregated communal life.”

I agree with him about the need for solid convictions and a disciplined communal life (about which more shortly). His call for a segregated communal life, though, strikes me as profoundly unrealistic. True, haredi Jews manage to insulate themselves by living in tightly knit, separatist communities; that is less true of Modern Orthodox Jews, with some resulting defections. But it is highly unlikely that the 85 percent or more of American Jews who are not Orthodox will, in any sense, secede from American life. Nor, in all likelihood, will more than a small minority of those not presently Orthodox choose to join that camp. What, then, can be done to strengthen the commitments of the vast majority of American Jews?

Conviction is a good place to start, but conviction usually flows from knowledge and experience. In surveying current trends in Jewish religious life for my book, it was striking to me how much effort synagogues and other Jewish institutions are investing to ratchet up Jewish literacy and entice more Jews to participate actively. This is evident in the hundreds of Conservative synagogues teaching men and women to read Torah and the haftarah, often for the first time in their lives; in the reappropriation and reconception of once discarded traditional practices by Reform rabbis; in long-established and start-up educational centers that teach Talmud and other sacred texts to previously uninitiated adults; and in the experiments of hundreds of congregations of all stripes with new synagogue music, liturgies, choreography, and opportunities for participation. Admittedly, we have no way to know whether these emerging expressions of Jewish religious life will alter the assimilatory trajectory for the large majority of Jews. But as Arkush reminds us and himself in his essay, the worst outcomes are not inevitable; sparks of Jewish life may be ignited with the proper interventions. Based on that conviction, the last Lubavitcher Rebbe created the most consequential Jewish movement of the past half-century, one that continues to inspire leaders in all sectors of Jewish life.

It’s easy to dismiss this call for hope rather than Arkush’s measured despair as mere sentimentalism. So let’s return to an analytical question about the role of contingency and human agency in history. In Arkush’s telling, the pot “continues to bubble away” with little variation over time. There is no room, it seems, to escape from assimilatory forces moving in a straight line through American history. Not only is the underlying assimilatory dynamic of American life unchanging, then, but groups are largely passive victims of this powerful force. Both of these points are debatable.

As baby boomers, both Allan Arkush and I have lived through eras when American culture was more hospitable to Jewish life than it is today. In the oft-maligned 50s, religion was valued as an aspect of American civic culture. In that decade, even Jews who may not have had much interest in religious expression experienced sufficient social pressure to join synagogues in order to keep up with neighbors flocking to churches. Matters are different today because elite culture is hostile to religion, viewing churchgoers with suspicion, if not enmity. That is evident in the dismissal of religious liberty as a cornerstone of American political life, and even a constitutional guarantee, by much of the academic, legal, and entertainment industries bestriding our culture. It is manifested too in the incessant onslaught against religious believers by those who shape opinion. In brief, keeping up with the Joneses today means devaluing religion, whereas it once meant feeling a degree of social pressure to conform to religious norms.

We both also lived through the revival of ethnic pride during the late 1960s and early 70s. American Jews who had been timid previously about displaying their Jewishness in the public square proudly wore kippot and Stars of David, and demonstrated en masse in support of Israel and Soviet Jewry. Today’s multiculturalism not only is viciously hostile to Israel but treats it as beyond the pale of civil discourse. As for Jewish group interests, those are dismissed as mere tribalism, even as much of the American populace splinters into ever more mutually antagonistic tribes. The great debate about ethnicity among today’s Jews does not focus on the best ways to enrich Jewish culture but whether Jews may claim to be a real minority or if they merely are part of an undifferentiated white populace. In two generations, Jews have gone from being the remnant of the most horrific genocide in human history to being labeled as “privileged” oppressors—and pathetically, many Jews swallow this nonsense.

In our lifetimes, in short, the wider culture has encouraged religious participation and dismissed it; Jewish ethnic pride has been strongly validated and severely contested, as has been Jewish support for Israel. At present, elite culture is highly antagonistic to collective Jewish needs, but, as in the past, that can change—especially if Jews take an active role in combatting some of the new thinking. Arkush cites the work of Horace Kallen, who advocated for cultural pluralism. Kallen, along with others such as Judah Magnes and Louis D. Brandeis, taught Americans to think differently about themselves. They fought a countercultural battle. Where are their counterparts among today’s Jewish intellectuals? With painfully few exceptions, today’s academics, journalists, and public intellectuals of Jewish background accede to the antireligious, anti-Israel, proassimilation culture, rather than resist and set forth a better course for America and its Jews.

Unfortunately, Jewish group survival is threatened not only by a changing external milieu but by unhelpful policies pursued internally by leaders who aspire to strengthen Jewish life. In the arena of philanthropy, for example, the preponderance of giving by Jews does not address specifically Jewish needs. That is a symptom of Jewish assimilation, of course. It does not help, though, when Jewish leaders bless this type of defection by labeling it as tikkun olam and therefore somehow an expression of deep Jewish convictions. This is destructive of American Jewish life, not reparative.

Even among those who do give generously to Jewish causes, priorities are often misguided. Many, for example, direct most of their giving to Israeli institutions but turn a blind eye to domestic Jewish needs. The problem does not lie in their commitment to the former but in their obliviousness to the needs in their own backyards. Who do funders imagine will succeed them as staunch Zionists if the next generation is deprived of a deep Jewish education? Decades of research have demonstrated the efficacy of formal Jewish education coupled with informal experiential Jewish programs in shaping identification with Judaism and the Jewish people. A rich Jewish education is the real birthright of American Jewish children.

The same is true of synagogues. Seven so-called emergent synagogues are awash in foundation money because they are seen as the postdenominational pilot programs for the future of American Judaism. But the many hundreds of synagogues of all denominations that are no less interested in religious renewal and no less open to innovation rarely receive a dime from leading funders. The current romance with novelty and “disruption” impedes support for the very institutions still serving and attracting the large majority of still-involved Jews.

Both educational institutions and synagogues if properly supported can address a crucial failing identified by Arkush, namely, wide-scale Jewish cultural and Hebraic illiteracy. It’s not only that most Jews don’t understand the Hebrew language of the prayers; they can’t decode the Hebrew alphabet. And what is the currently favored solution? Prayer books, and even haftarot, in transliteration. If the short-term goal is to enable every attendee to sing along, that makes sense, but it won’t help Jews become more knowledgeable and committed. Meanwhile, Jewish schools are prioritizing happy Jewish experiences over teaching the formative texts of Jewish civilization. If the great question many Jews are asking in our time is “why be Jewish?” surely the accumulated depth of Jewish thinking over the long course of our history will offer a more inspiring answer than “because it’s fun.”

Lurking beneath the decline of Jewish life are spiraling intermarriage rates. Though waved away by many as no more under anyone’s control than the weather, marital decisions result from human choices, not meteorological vagaries. People decide to marry, and communal institutions decide how they will respond. Decade after decade, every survey of American Jews finds evidence of a vast difference in the ways that families with two Jewish spouses live as Jews compared to those with only one. As noted in an important report early in the century, this is a tale of two Jewries, with in-married Jews far more involved in all aspects of religious and group life than the intermarried. It takes a high degree of self-delusion not to see intermarriage as both the most significant symptom of the dissolution of American Jewish life and its main cause. The Pew study found more than two million individuals of some “Jewish background” who identify with a religion other than Judaism. In the overwhelming majority of cases, they are descendants of intermarried parents or grandparents. And still, one Jewish institution after another has decided to normalize intermarriage.

The examples I have cited of misguided policymaking can be multiplied many times over. They point to a dimension of the American Jewish narrative too often overlooked when we speak about assimilation, including in Allan Arkush’s stimulating essay. We are up against not only external forces eroding Jewish participation but also the poor choices made by Jews—including some of their leaders—who are all-too-willing accomplices to the dissolution or dumbing down of Jewish life. Rather than treat assimilation as an inexorable social process, we would do better to think about ways in which we have agency to make smarter decisions. Reversing direction to pursue policies that will educate our people and socialize them into living rich Jewish lives may seem a pipe dream to some. But if pursued, it offers a chance to rebuild what once was a confident American Jewry—and render American Jews a truly exceptional minority.

Looking for the other items in this symposium? We recommend you begin with Allan Arkush’s cover article, “In the Melting Pot.” Then, look at responses from:

- David Biale, whose work figures in Arkush’s essay

- Edieal Pinker, who weighs in with a new statistical analysis

- Erica Brown, who speaks movingly about the charred remains of Jewish culture that cling to the bottom of the American melting pot

Finally, Allan Arkush responded to his critics.

Suggested Reading

Neither Friend nor Enemy: Israel in the EU

After five years at the European Parliament, the author reflects on Israel's place in the discourse of the EU's chattering (and legislating) class.

Our Lady in Tehran

In Tehran, the Mossad has orchestrated a complex and brazen operation as part of a last-ditch effort to cut the capital’s power supply so that the Israeli Air Force can take out Iran’s nuclear program

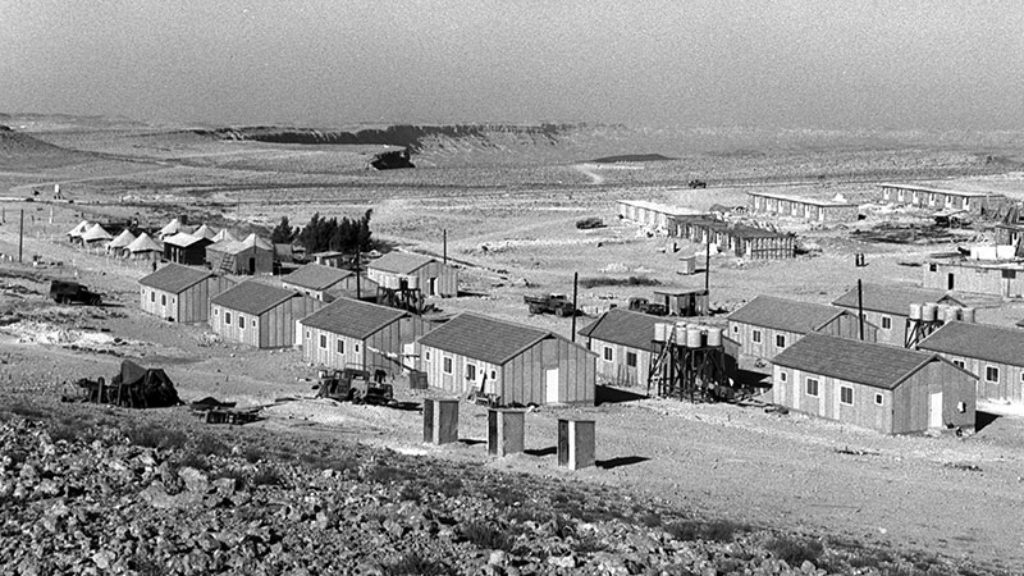

Seventy Years in the Desert

At the 1965 International Bible Contest, David Ben-Gurion posed some of the questions. He also asked two to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

Berdyczewski, Blasphemy, and Belief

Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, one of the towering figures of the rabbinical establishment, found deep lessons about faith in the writings of the Nietzschean heretic Micha Josef Berdyczewski.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In