Simon Wiesenthal and the Ethics of History

If there was anything in particular that prevented Simon Wiesenthal from becoming, after S.Y. Agnon, the second Jew from Buczacz to win a Nobel Prize, it was probably his relationship with Kurt Waldheim. Back in the 1960s, when he was Austria’s foreign minister, Waldheim had helped Wiesenthal to defend himself against rumors spread by Communist bloc countries that he had been a Nazi collaborator during World War II.

Two decades later, after he had served as Secretary-General of the UN and was running for the presidency of Austria, Waldheim’s actual Nazi past finally came to light. Grateful for his earlier support, Wiesenthal, who should have known better (and probably did), dismissed the case against Waldheim as mere “gossip” spread by his political adversaries. This landed him in a nasty public battle with the World Jewish Congress, which lobbied to have Waldheim labeled a war criminal, placed on the United States’ Watch List, and banned from entering the country. In 1986, at the height of this scandal, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to fellow survivor Elie Wiesel. “It is reasonable to assume,” writes Tom Segev in his new biography, “that Wiesenthal didn’t get the prize” at the same time “because he was at the center of a raging controversy.”

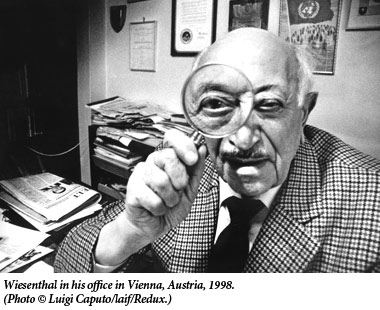

This was scarcely the only controversy that Wiesenthal sparked. Throughout his career as a Nazi hunter he had both fervent admirers and angry detractors. In the eyes of some, he was the matchless hero who inspired Frederick Forsyth’s novel The Odessa File, a man who had dedicated himself, often at risk to his own personal safety, to tracking down Nazi war criminals, and bringing them to justice. Sitting in a modest office in Vienna, behind heavily fortified steel doors, he managed—without a state’s intelligence apparatus or financial resources—to find what he called “the murderers among us.” A United States Congressional Resolution lauded him as being “instrumental in the capture and conviction of more than 1,000 Nazi war criminals, including Adolf Eichmann, the architect of the Nazi plan to annihilate European Jewry.” But Isser Harel, the mastermind who headed Israel’s Security Services at the time of Eichmann’s capture, insisted that Wiesenthal played no role in the operation. In fact, according to Harel, Wiesenthal almost sabotaged the whole effort when he shared information that had been given to him in strictest confidence. While Harel’s account of this episode in The House on Garibaldi Street may be somewhat self-serving, he is by no means the only one to denounce Wiesenthal as a self-promoter and even a fraud. Other critics have accused him of falsely taking credit for finding criminals and repeatedly inventing information unsupported by any data.

This criticism has been echoed by government agencies. In 1986, the Canadian government’s Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals submitted a 1,000-page report to the country’s Governor General. While acknowledging that there were indeed Nazi war criminals in Canada and urging action against them, the report also castigated Wiesenthal for having “grossly exaggerated” their numbers. The lists he gave the Canadian government were “nearly totally useless” and he refused to turn over to the Commission information they needed for their investigation, which he claimed to have in his files. The Office of Special Investigations (OSI) of the US Department of Justice was also severely critical of him. In 1979, the OSI’s director told Wiesenthal in strict confidence that it had traced one of Eichmann’s accomplices to California. Wiesenthal proceeded to leak the information to the press in a way that suggested that it was he who had found the man. The OSI eventually severed all contact with him.

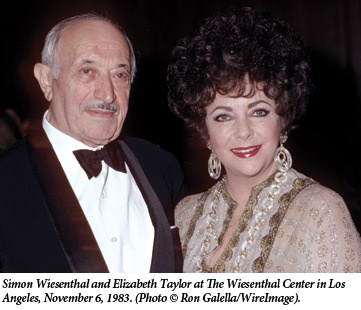

Was Simon Wiesenthal an intrepid hunter of mass murderers who was worthy of all the tributes he received from such figures as Jimmy Carter and Elizabeth Taylor (who wrote to him “I love you and we all need you”)? Or was he in fact more of a charlatan than a hero? While writing a book on the Eichmann trial, I often had occasion to ask myself these questions. Upon discovering that Wiesenthal’s numerous autobiographies and innumerable interviews tell a variety of different and irreconcilable stories, my suspicions of the man grew markedly. I was excited, therefore, when I heard that Tom Segev was writing his biography. Segev has made a career of slaughtering the sacred cows of contemporary Jewish and Israeli history. A newspaper columnist who is also the author of several works of history, he has more than once plunged deep into the archives. If Wiesenthal was in fact a fraud, Segev would be able to prove it—and would do so, no doubt, with relish. A little later, when I learned that Segev had actually come to the conclusion that Wiesenthal’s critics were wrong, I was pleasantly surprised, albeit curious.

Segev makes his position clear from the beginning of this substantial and thoroughly researched volume. With uncharacteristic enthusiasm, he describes Wiesenthal as a man of “broad humanity,” a “tireless warrior against evil and a central figure in the struggle for human rights.” He even goes so far as to agree with an official at the Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles’ observation that “if he had not existed, Wiesenthal would have to be invented, because people all over the world, both Jews and gentiles, needed him as an emblem and a source of hope.” He not only “sparked” the imaginations of Jews and gentiles, but “enchanted them, thrilled them . . . weighed on their consciences, and”-one is surprised to hear Segev say such a thing about anyone-“granted them a consoling faith in good.”

Nevertheless, despite his high regard for Wiesenthal, Segev gives due attention to the other side of the story. Indeed, he confirms many of the charges made by his critics. Consider some of the terms he uses to describe Wiesenthal’s modus operandi: He “fabricated” evidence, “snatched” stories out of thin air, “fantasize[d]”, was “often inaccurate,” “came up with things that never happened,” “invented” facts, “claim[ed] credit” for things he never did. Indeed, he sometimes “wove things out of his imagination.”

As Segev shows, Wiesenthal’s account of his experiences during the years of the Holocaust is clearly fabricated. When he visited Auschwitz in 1994, he told a biographer who accompanied him that he had been brought to Auschwitz on a death train. Miraculously, he had been transferred a few days later. Segev acknowledges that this typified Wiesenthal’s “set pattern” of “magnify[ing] his ordeal” while adding “a dash of drama.” He did the same thing when he enumerated the camps and prisons in which he had been incarcerated. Immediately after liberation he said he had spent time in four camps. During the 1950s, the number grew to nine and then to eleven. By the early 1980s, it had reached twelve, including Auschwitz. Joseph Wechsberg, who co-authored Wiesenthal’s autobiography, wrote in the introduction that he had been in “over a dozen.”

The miraculous was also woven into his account of how he had been saved from a certain death in Janowska. On April 20, 1943, Hitler’s birthday, he was among a group of prisoners who were taken outside the camp to be shot. Just as his turn came he was pulled out of line and told to return to camp to draw a birthday poster for Hitler. He was the only one in the group to survive. The main elements of this story are indeed true. On that day in 1943 a group of prisoners were taken from Janowska and shot. One was pulled from the line just before he was to be killed and told to return to the camp. But it wasn’t Wiesenthal’s story. The man to whom this happened was apparently Leon Wells, Wiesenthal’s friend.

Wiesenthal’s claims about tracking war criminals in the post-war years are likewise riddled with exaggerations, if not outright falsehoods. Let us return to the Eichmann case. In 1953, Wiesenthal learned from an Austrian stamp collector that Eichmann was in Argentina. He passed this information along to the World Jewish Congress, which in turn transmitted it to the CIA, which did nothing. Had someone acted on this information at the time or even remembered it six years later, when Eichmann was found in Argentina by others, Wiesenthal would have deserved some of the credit. But that didn’t happen.

In fact, the key information that led to Eichmann’s capture came from three unlikely characters: Lothar Hermann, a nearly blind, half-Jewish German immigrant to Argentina; Hermann’s teenage daughter Silvia; and Fritz Bauer, a German Jew who had returned to Germany after the war and became a Federal prosecutor. It is true, as Wiesenthal claims in one of his autobiographies, that in 1959, even as preparations were being made to capture Eichmann, he shared with the Israelis his strong suspicions about Eichmann’s whereabouts. But what he told them was that he was virtually certain that Eichmann was hiding in northern Germany, a hemisphere away from his actual location.

Wiesenthal also claimed to have tracked down Dr. Josef Mengele to the Greek island of Kythnos, where he sent a reporter to find him. On Wiesenthal’s account, the reporter found only two buildings on the island, an inn and a monastery. The innkeeper told him that on the preceding day a yacht had ferried away “a German and his wife.” The reporter showed Mengele’s picture to the innkeeper and some monks who confirmed that he had been there. However, when the reporter subsequently read Wiesenthal’s account, he said that there was no monastery on the island and, more importantly, no report of a German who had recently visited the island or left the previous day. It was, simply put, “all wrong.” Over the years, Wiesenthal repeatedly announced that he knew precisely where Mengele was. Most of these pronouncements, it seems, were mere guesses designed to win media attention.

Wiesenthal did indeed help to track down a number of war criminals, far fewer than the 1,000 for which he is often credited, but probably far more than anyone else. More importantly, he shone a public spotlight on the question of Nazi war criminals who had not been brought to justice. He did so despite the opposition of those who wished to push the whole matter under the rug, lest it open old wounds by calling attention to the wrongs committed by people who had been “rehabilitated” and fully integrated into post-war society. Believing that the demand for justice trumped all other considerations, Wiesenthal went wherever the trail led and sometimes, as we now know, where it did not lead. It is thus unfortunate that his fabrications and falsehoods now threaten to overshadow his real accomplishments.

Somewhat surprisingly, Tom Segev, a journalist who is usually zealous in his search for truth and contemptuous of those who distort it, is not unduly bothered by Wiesenthal’s mendacity. He makes excuses for him, claiming that Wiesenthal’s proclivity for “exaggerat[ing] his suffering” and spinning “fantasies about his survival” was a means of “push[ing] out of his consciousness the real atrocities he had experienced.” His untrue statements emanated, Segev suggests, from a “profound sense of guilt” for having survived when his whole family had perished.

Why is Segev so forgiving of Simon Wiesenthal’s many lapses? Perhaps we can arrive at an answer by considering Wiesenthal’s most egregious distortion of the historical record and Segev’s response to it. In the 1970s, Wiesenthal began to refer to “eleven million victims” of the Holocaust, six million Jews and five million non-Jews, but the latter number had no basis in historical reality. On the one hand, the total number of non-Jewish civilians killed by the Germans in the course of World War II is far higher than five million. On the other hand, the number of non-Jewish civilians killed for racial or ideological reasons does not come close to five million (though it no doubt would have exceeded it if the war had ended in a German victory). Nevertheless, Wiesenthal’s contrived death toll, with its neat almost-symmetry, has become a widely accepted “fact.” Jimmy Carter’s Executive Order, which was the basis for the establishment of the US Holocaust Museum, referred to the “eleven million victims of the Holocaust.” I have been to many Yom Hashoah observances-including those sponsored by synagogues and Jewish communities-where eleven candles were lit. When I tell the organizers that they are engaged in historical revisionism, their reactions range from skepticism to outrage. Strangers have taken me to task in angry letters for focusing “only” on Jewish deaths and ignoring the five million others. When I explain that this number is simply inaccurate, in fact made up, they become even more convinced of my ethnocentrism and inability to feel the pain of anyone but my own people.

When Israeli historians Yehuda Bauer and Yisrael Gutman challenged Wiesenthal on this point, he admitted that he had invented the figure of eleven million victims in order to stimulate interest in the Holocaust among non-Jews. He chose five million because it was almost, but not quite, as large as six million. When Elie Wiesel asked Wiesenthal who these supposed five million victims were, Wiesenthal exploded and accused him of suffering from “Judeocentrism.” In recent months, Wiesenthal’s concoction has been further improved upon by a group of rabbis and imams who visited Auschwitz under the aegis of the US State Department. The statement they issued after their visit referred to the “twelve million victims, six million Jews and six million non-Jews.” Now we have parity. One wonders what’s next.

Segev, for his part, explains away Wiesenthal’s invention of the “eleven million” as his means of stressing “the brotherhood of all the victims,” something Jews generally fail to do. He lauds Wiesenthal for “judg[ing] people by their deeds and merits rather than by their group affiliation. This was the basis for his humanistic views and his faith in justice. It was the basis for his belief in good and his longing for conciliation.”

Segev, who is deeply troubled by what he perceives as Israel’s leaders’ narrow, particularistic Weltanschauung, apparently sees Wiesenthal’s broad universalist revisionism as therapeutic. He doesn’t seem to grasp that it can also be quite injurious. Any falsification with respect to the Holocaust, whatever its purpose may be, gives comfort and solace, not to speak of ammunition, to Holocaust deniers. It enables them to turn the tables and to claim that the “defenders of the Holohoax” are the ones guilty of fabricating history.

However, inventions such as the figure of “eleven million” would be unjustifiable even if there were no Holocaust deniers. The best reason to stick to the truth is the one offered by the members of Oyneg Shabbes, the group that dedicated itself to documenting every aspect of life in the Warsaw ghetto. In Who Will Write our History? Samuel Kassow quotes Emanuel Ringelblum, the group’s leader:

We wanted the simplest most unadorned account possible of what happened in each shtetl and what happened to each Jew (and in this war each Jew is like a world in itself). Any superfluous word, any literary exaggeration grated and repelled . . . [I]t is unnecessary to add an extra sentence.

The goal, Ringelblum said, was “a photograph of life. Not literature but science.” The situation was bad enough. No exaggeration was necessary.

In 1944, Ringelblum’s associate, Rachel Auerbach, said much the same thing in different words: “The mass murder, the murder of millions of Jews by the Germans is a fact that speaks for itself . . . one must approach this subject with the greatest caution, in a restrained and factual manner.” But the most succinct statement of this position was penned by an anonymous individual who filled out a survey distributed by Oyneg Shabbes to inhabitants of the ghetto. The respondent scrawled a single word in the margin of the questionnaire, in capital letters: FACTS.

Suggested Reading

Endless Devotion

Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks' new translation of the siddur moves Hillel Halkin to reconsider Jewish prayer.

“Wherever You Go, I Will Go”: Reading Ruth 1:16-17

It is traditional to read the book of Ruth on Shavuot. Leon Kass has been reading it with his granddaughter, and the result is a new book.

Bread and Vodka

Mendel Osherowitch's 1933 book about life in Ukraine not only bore rare eyewitness testimony to one of the worst atrocities in a barbarous century; it did so from the vantage point of a brother of two of the perpetrators.

Agnon, Oz, and Me

Over the years, I’ve spoken privately with several Israeli novelists but with only two of the internationally famous ones. And these very brief conversations took place more than 40 years…

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In