Bread and Vodka

In February 1932, the New York-based journalist Mendel Osherowitch, a native of Ukraine, was commissioned by Abraham Cahan, editor of the Yiddish-language newspaper the Forverts, to visit theaters and taverns in Russia and “speak with common people in the streets, Jews and non-Jews.” Cahan told him to send dispatches chronicling the minutiae of everyday life rather than commentary on the political situation. But Osherowitch’s insights into the brutality of early Stalinism and the false hope communism lent to a Jewish community soon to be barbarically assaulted, first by the Nazis, then by Stalin himself, were a trenchant condemnation of the Soviet enterprise.

Kashtan Press has now published a translation of Osherowitch’s 1933 Yiddish book based on those dispatches, chiefly because it provides a rare account of the early stages of the Holodomor, in which four to five million Ukrainians died in a genocidal, state-engineered famine. But it also provides a unique look into Jewish suffering (and complicity) in the period. Osherowitch’s honest account in direct, no-nonsense Yiddish (he spoke fluent Russian and Ukrainian, as well), superbly translated by Sharon Power, complements the harrowing contemporary testimony of the Welsh journalist Gareth Jones, whose reports of starvation and cannibalism in Ukraine were cynically dismissed. At the time, New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty concluded that “conditions are bad, but there is no famine” after what he deemed “exhaustive inquiries.” As we learn in Anne Applebaum’s scholarly account of the Holodomor, Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, Duranty’s credulous reporting satisfied not only the Russian authorities but a Roosevelt-led American administration keen to maintain friendly relations with Stalin in the face of developing threats from Germany and Japan. It also won Duranty a Pulitzer Prize. Osherowitch’s account remained unread by anyone outside the Yiddish-speaking community until now.

Osherowitch’s dispatches were delivered over a two-month period. He began in Moscow, encountering impoverished locals who wore the same shoes for five years and traveled by absurdly slow trams to try to preserve the leather. He noticed how Muscovites queued for food in freezing conditions while foreign fellow travelers and journalists of Duranty’s ilk enjoyed fried chicken and other delicacies in exchange for positive appraisals of the Soviet enterprise. Sympathetic and observant, with an eye for detail, he saw Soviet Russia for what it was, the despondency and poverty of its population.

In Moscow, he met his brother Buzi, an enthusiastic party activist whose catchphrase “It’s all set!” became increasingly sinister as Osherowitch’s two-month journey progressed and he saw more unsettling scenes. Before the two brothers embarked on the first train to Ukraine, a Muscovite advised Osherowitch to bring bread for his mother. Osherowitch registered his surprise: that fertile region had always been Russia’s breadbasket. While waiting for yet another train, Osherowitch heard Buzi’s rose-tinted views about Ukraine’s ability to feed itself contradicted by a Ukrainian peasant, “Why are you telling him fibs? . . . Better to tell him we don’t have any bread in the house!”

Osherowitch’s book not only bore rare eyewitness testimony to one of the worst atrocities in a barbarous century; it did so from the vantage point of a brother of two of the perpetrators. While Buzi worked for the secret police, Osherowitch’s brother Daniel was a pistol-toting bully whose task was to force peasants to hand over their precious grain at gunpoint. Osherowitch described him as “strong as iron, hardened, armed” before making a devastating observation: “Only barely, at the corner of his mouth, did you notice a smile, betraying a small trace of the good nature our family was known for.”

When he returned to his hometown of Trostianets, he found Jewish life changed beyond recognition. The klayzl (study hall) was now a cinema, the beit midrash a school for modern languages, the kloyz (which Powers renders as a “small synagogue, prayer and study house”) a bottle-cover factory. Only on the High Holy Days did the old shul fill, but many of the pious avoided it, afraid their presence there would compromise children who were party members. Yet for Jews, Osherowitch was frequently informed, bolshevism had been entirely beneficial.

“We gained everything,” one apparatchik informed him:

Under the Czar we had no rights. The Revolution gave us our rights. In the Soviet Union there is no high position a Jew is not permitted to occupy. . . . All doors are open for us, in the schools and in government. In the army you find Jewish commanders. In many cities you’ll find Jews in the highest offices, taking up positions like those of the former governors.

In the Soviet Union, Jews also had protection against the sort of pogrom carried out in Trostianets by the White Army in May 1919. Five hundred men, women, and children were herded into an industrial building and slaughtered while barishnyes (young ladies) “played on a piano, muffling through music the laments and screams of the victims, which spilled out along with their blood.”

Even against the backdrop of centuries of Jewish persecution in Ukraine, so scarring was the memory of the pogrom that the Jews of Trostianets created their own time frame—“before the catastrophe” and “after the catastrophe.” A stone memorial to the massacre, Osherowitch noted, was regularly vandalized by the locals. Typically such a keen observer, he oddly attributed this to shame felt by perpetrators. Less than 10 years after his visit, in 1941, the Germans set up an extermination camp on the site of Trostianets’s hated kolkhoz (collective farm). Around 200,000 inmates, most of them Jews from the Minsk Ghetto, perished there.

Trostianets had a factory that had once been dedicated to sugar production and a railroad connecting it to Odessa and Kiev. By the time of Osherowitch’s visit, the factory only produced vodka. Even the local Jews, who were not known as drinkers, were driven to it by the endless, crushing lack. Osherowitch described a “fine gentleman” who used to wear “a pressed collar and cuffs,” even on weekdays, reduced to “a dirty peasant’s fur coat and . . . shabby sheepskin hat.” “You wonder we Jews drink so much vodka, why we are drunk?” the man asked. “It’s simple! A loaf of bread costs twelve to fifteen rubles. A litre of vodka costs only two rubles. If you buy a litre of vodka, get drunk and pass out for a day, sometimes for two, you forget you’re hungry.”

Perhaps Chlib could have been the book’s title: bread was the scarcest commodity, the difference between life and death, cherished even in its stalest, moldiest form by a starving population. In Red Famine, Anne Applebaum describes how “organized teams of policemen and local Party activists, motivated by hunger, fear, and a decade of hateful propaganda, entered peasant households and took everything edible: potatoes, beets, squash, beans, peas, and farm animals.”

In overcrowded trains and stations, Osherowitch frequently came across vast crowds of peasants in search of bread (not work, as a Soviet apparatchik cynically informs him). These encounters inspired some of his finest, fiercest writing:

Two men in rags stood near a round iron stove. It had long been as cold as a corpse’s head. Their half-bare feet were wrapped in straw. Scraps hung down from the rags they wore as clothing and here and there the naked flesh of these poor and starving people peeked out. One held his hands in his pockets, his feet pressed together, leaning his body on the cold stove, propped up in a corner. His eyes were closed. You couldn’t tell whether he was sleeping or just didn’t want to open his eyes, knowing that today, just like yesterday, and the day before, and all the days of the year, he would only see what he had seen before and didn’t want to see again.

His brother Buzi, the secret policeman, was unmoved: “Such is the march of history! The old generation needs to die away, to make room for the younger one. The Soviet Union is not a country of today but of tomorrow. It’s all set!” Osherowitch saw clearly for himself and showed Forverts readers the results of such thinking. Lishnie liudi (superfluous people) received the smallest portions of bread. “Society has no obligations with respect to them,” Buzi observed, “so, in consequence, their situation is truly dire.” After the book was published, Buzi denounced Osherowitch as “a capitalist lackey” whose eyes were “sealed shut with dollars.”

Jews, as Osherowitch saw in Trostianets, could flourish only if they abandoned their religion and toed the party line. In Odessa, one family offered him not only bread but herring, pickles, and wine. How was this possible? “I have three ‘kohanim,’” his host told him, referring to his three sons in the Communist Party.

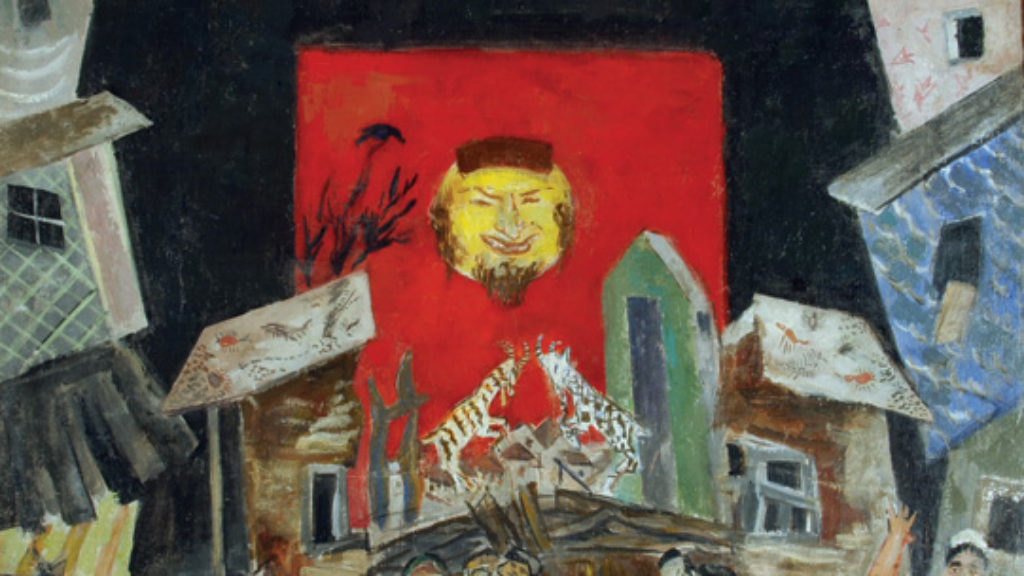

But such “kohanim” brought more curses than blessings to their people. When Osherowitch visited the Mendele Sforim Museum, named after the great Yiddish writer, a manager described the Judaica in the collection to him as “symbols of power . . . the power of darkness,” which proved that “Jewish clericalism stood with the Russian monarchy.” To contemporary readers, the experience eerily evokes Hitler’s intended “Museum of an Extinct Race.”

Osherowitch’s somber text is intermittently lightened by accounts of the sheer absurdity of life in Soviet Russia. Customers who were permitted to buy cherished items at state stores found themselves obliged to purchase something they did not want in addition, simply because there was a surplus:

Nobody knew who needed these bells. . . . But in the government shops they had to get rid of them. So whoever came in to buy something was made to buy a bell. They simply refused to sell anyone anything they might request unless they also bought a bell. So people were walking out on the streets of Odessa ringing bells. . . . Everyone is happy in Odessa and here was the proof of it—the city’s people were going about on the streets, ringing bells. What more evidence does one need? Bicycle pumps and bells aplenty but there isn’t any bread!

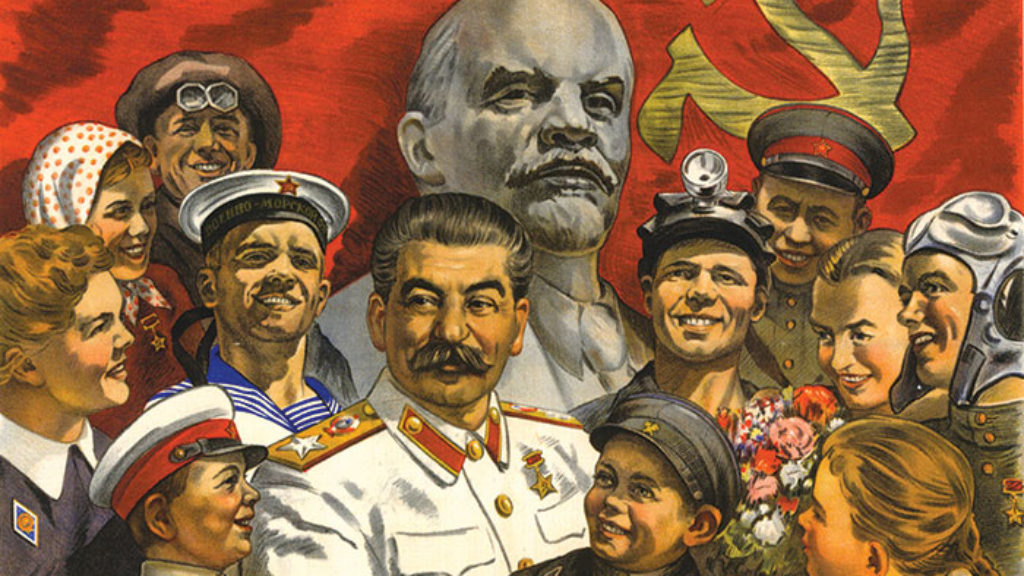

While Stalin (who in one happy typo becomes “Stain”) was cursed by his victims, the memories of the mummified Lenin and exiled Trotsky were celebrated in a nostalgic, deluded yearning for better days. But ruthlessness was at the heart of the Bolshevik enterprise from the get-go. When Commissar of Justice Isaac Steinberg asked, “Why do we bother with a Commissariat of Justice? Let’s call it frankly the Commissariat for Social Extermination and be done with it!” Lenin supposedly replied, “Well put . . . that’s exactly what it should be . . . but we can’t say that.”

Toward the end of the book, yet another in the long line of apparatchiks spouts another platitude, “You just don’t agree with our methods, with the way in which we are building socialism. Well, let history judge us!”

It has.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Playing the Fool

Of the many varieties of anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism, that have plagued the Jews over the centuries, two recurrent general patterns can be identified by the holidays that celebrate triumphs over them: Purim and Hanukkah.

Jews, Revolutionism, and Doublethink

Even in the Gulag, it was difficult to give up the belief in the Revolution. Take Evgenia Ginzburg, for example . . .

In (Partial) Defense of Doublethink

How does one survive psychologically under the control of chaotic evil? Take Evgenia Ginszburg, for example . . .

Lenin and Maimonides

Lenin and Maimonides, Communist leaflets and Hebrew verse: What could be more different, in language, in sensibility, in world view?

Herbert Yoskowitz

Powerless corrupts but absolute powerlessness corrupts absolutely . I am paraphrasing Rabbi Yitz Greenberg . This story as told in the review appears to confirm his hypothesis .

Alexander Gendler

When working with the book which is now one of the main "witnesses" for Ukrainian nationalists of the Jewish guilt for Holodomor, a Jewish publication and a Jewish reviewer needs to be more careful. There was a real good reason for Jews of that part of the Soviet Union to be very apprehensive of Ukrainian peasants at that time. A large portion of more than 300,000 Jewish victims of massacres during the Russian Civil War was murdered by ethnic Ukrainian peasants. The May 24 murders of Jews Trostianets, mentioned by the reviewer, were not committed by the White Army but by the local Ukrainian band led by the warlord Lesitsa. In 1921, the Soviet authorities declared amnesty for these cannibals who enjoyed their freedom and financial wellbeing before the beginning of a horrific socialist robbery of peasants in 1929, called collectivization. Those Jews that ended up serving in state institutions of repression naturally took part in suppressing this resistance and were also highly motivated. Do you suggest that they should have forgotten the murders of their Jewish relatives and neighbors? Was it they who caused Holodomor or was Holodomor a result of the socialist barbarity created by the Russian revolution which to a large extent for its victory relied on these peasants to rob Polish and Russian landowners of their property? It is shame that a serious publication like yours, allows itself to be used by enemies of our people.