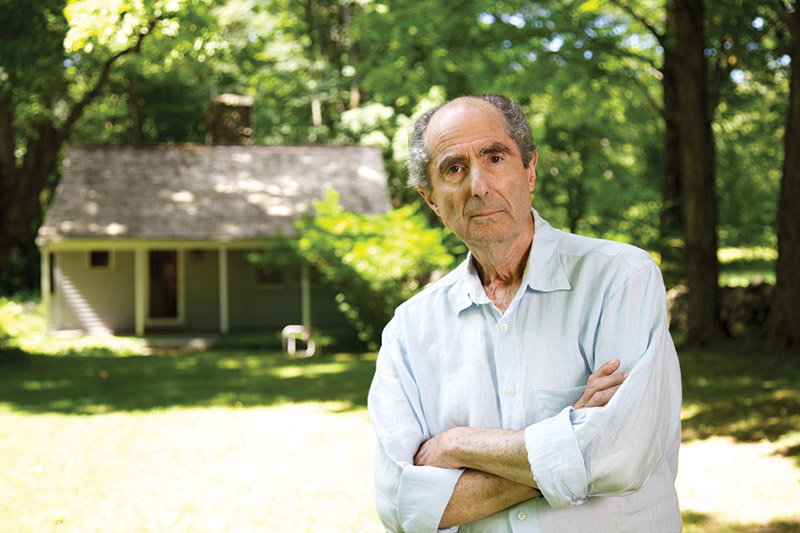

Getting Out from Under: The Philip Roth Story

Between 2012, when Philip Roth announced that he would retire from writing, and 2018, when he died at eighty-five, he was anything but idle. Working with his authorized biographer, Blake Bailey, Roth returned to the Augean task that had consumed him throughout his career: fashioning a self out of the muck of experience. According to Bailey, the novelist wrote long self-explanatory essays for his biographer. “He sent me thousands of pages, hundreds of files, and attached to each file was a meticulously typed memo telling me exactly what to think about the context of that file,” Bailey said at a panel in 2019. Bailey took as his epigraph Roth’s instruction, “I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting.” By the time you reach the last of the book’s 912 pages, however, Roth’s directive may strike the reader as disingenuous. Roth commissioned his biography—indeed, he began trying to commission it decades before he met Bailey—precisely to rehabilitate himself, which is not the same as being interesting. In particular, Roth felt that he had been unfairly besmirched by a damning memoir by his former second wife, the actress Claire Bloom, and he was not a man to let go of a grievance. Bailey’s biography was supposed to give him the last word.

Philip Roth: The Biography doesn’t do that, though not for lack of trying. Whether by flooding Bailey with material or drowning the poor man in his apparently considerable personal charm, Roth almost managed to keep this version of himself under his control. The biographer sides with his subject in all his major battles. But the reader, or this reader anyway, is not convinced—first, because the facts aren’t particularly exculpatory, and second, because Roth himself had long since undermined his own case.

Roth’s great talent was for self-mocking self-replication. His alter egos double, attack, redouble, counterattack, pick fights with their author. Roth’s chief doppelgänger, Nathan Zuckerman, understands Roth much better than Bailey does. In the mostly autobiographical The Facts, Roth writes a letter to Zuckerman in which he declares that he has finally managed to strip himself bare, to shed “masks, disguises, distortions, and lies.” This Roth will be “the antidote and answer to all those fictions that culminated in the fiction of you,” he says. The “fiction of you” rolls his eyes. Autobiography is “probably the most manipulative of all literary forms,” Zuckerman informs his creator, and Roth’s account of himself is defensive and full of evasions. Roth’s “medium for the really merciless self-evisceration, your medium for genuine self-confrontation,” concludes Zuckerman triumphantly, “is me.”

Zuckerman has a point. Rage and self-attack were Roth’s muses, or, to invoke a biblical story Roth used as an epigraph for Operation Shylock, his Jacob and the angel, who wrestle for reasons Jacob never quite understands—though the struggle yields a blessing and a new identity. Likewise, indignation tinged with shame dragged Roth to his desk every day and generated twenty-seven novels, as well as short stories and essays. But not until Sabbath’s Theater, Roth’s favorite novel, did he manage fully to exploit both his insecurity and bottomless sense of having been done to. Mickey Sabbath is “the great clown of anger,” in Roth’s words, a lord of misrule, transmogrifying wrath and self-loathing into extreme—and, to my mind, extremely funny—sexual perversity and shameless violations of basic decency.

Why all the anger? In Ira Nadel’s new critical biography, Philip Roth: A Counterlife, a book whose title already seems to anticipate that it will be overshadowed by Bailey’s doorstop, we learn that Roth admitted to being seriously angry at his two ex-wives and to funneling that anger into his work. But he also insisted that “anger isn’t just anger—it’s a helluva lot more.” What he meant is that anger served an aesthetic purpose, says Nadel. It makes a writer serious. I’d add that, for Roth, it gave him permission to take liberties as well as employ his propulsive, prosecutorial style.

The inevitable examples of Roth’s liberty-taking are the novella Goodbye, Columbus, the short story “Defender of the Faith,” and, of course, Portnoy’s Complaint. Roth has to have known that each story’s paired caricatures—materialistic Jews versus a bookish Jew in Goodbye, Columbus, a rule-following Jew versus a trickster Jew in “Defender of the Faith,” and philistine Jews versus an oversexed Jew in Portnoy’s Complaint—would brand him as a self-hater. According to the anger theory of literary production, the Jewish establishment’s rage and Roth’s own hurt and fury would be necessary to his art. “A writer has to be driven crazy in order to see,” critic Claudia Roth Pierpont quotes the novelist as saying in her Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books.

Roth also seems to have needed to be betrayed. The greatest betrayal of his life, as he saw it, was a foreseeably disastrous marriage at twenty-six to an abused and abusive Midwestern divorcée named Maggie Martinson with two children from a previous marriage. Roth felt that Maggie tricked him into matrimony with a scheme so brazen that no “half-formed, fledgling novelist” could have anticipated its “diabolical ironies.” In 1959, Maggie told Roth she was pregnant, then went out and bought urine from a pregnant woman in Tompkins Square Park in New York to back up her claim. Their marriage was horrific. Roth cheated. Maggie, who was probably an alcoholic, grew floridly paranoid, and after their separation, exacted ruinous alimony. Roth was openly jubilant when she died in a car crash in 1968.

Once again, Zuckerman explains the author to himself. In that letter in The Facts, Zuckerman makes the reasonable point that Maggie wasn’t “something that merely happened to you, she’s something that you made happen.” There she was, Zuckerman declares, “waiting like your moll in the getaway car, embodying everything the Jewish haven was not, including the possibilities for treachery.” Maggie had to be married and striven against “because the things that wear you down are the things that nurture you and your talent.” Maybe, but not necessarily. Roth’s anger could also yield thin, self-pitying revenge novels like When She Was Good and I Married a Communist, based on his marriages to Martinson and Bloom, respectively. Sometimes even Zuckerman let Roth get off easy.

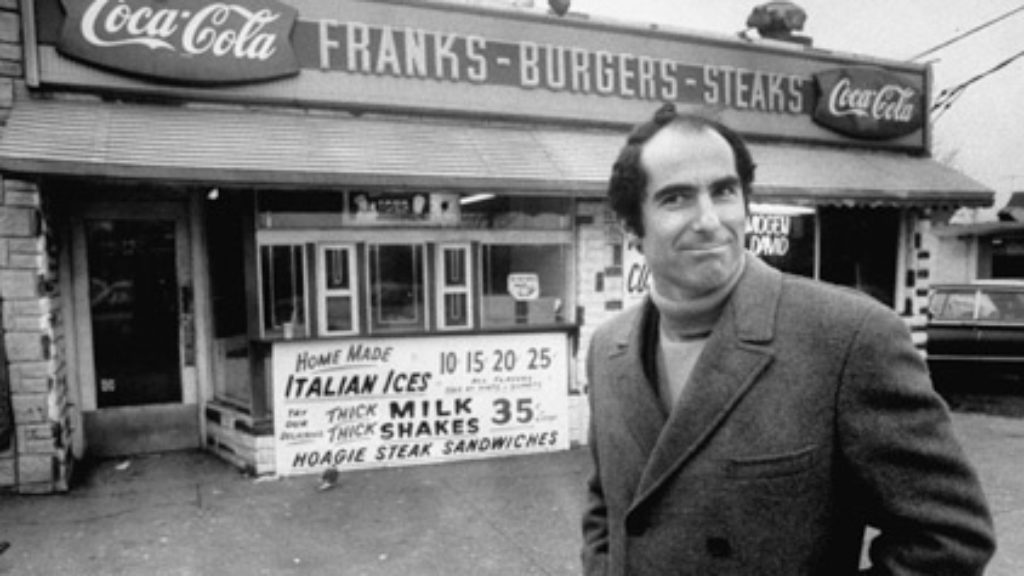

Roth’s childhood gave him a grounding solid enough to withstand the trouncing he later gave it. In Bailey’s telling, he really was the nice Jewish boy he worked so hard to cast off. He felt safe in the cozy Jewish enclave of Weequahic in Newark, New Jersey. Weequahic boasted 17 “little synagogues,” according to Bailey—perhaps he means shtiebels (Bailey is not particularly insightful or precise on midcentury American Jewish culture). Throughout his adult life, Roth would recall Weequahic with Proustian affection—the suburban New Jersey of his youth, that is, before the riots of the 1960s turned Newark into a “carcass” of itself, as Seymour “the Swede” Levov says in American Pastoral. In truth, even the old Newark wasn’t always idyllic. The Facts recounts a near-pogrom at a football stadium, complete with rampaging gangs swinging baseball bats, after the largely Jewish Weequahic High School team defeated a non-Jewish rival.

But Roth got what he needed to flourish. His mother, Bess, offered unconditional worship, and his father, Herman, though a nudge, taught the value of hard work as he fought to rise through the ranks of an insurance company that didn’t see Jews as management material. These are familiar stories. Less well known is that Philip learned how to do shtick at afternoon Hebrew school, where the students made fun of their “hapless refugee melamed,” Bailey writes. Otherwise, “Philip was an all-American boy who loved baseball,” his father recalled. Roth wrote in The Facts that “if ever I had been called on to express my love for my neighborhood in a single reverential act, I couldn’t have done better than to get down on my hands and knees and kiss the ground behind home plate”—the Holy Land of his childhood.

At the same time, Roth was “exogamous”—his word—meaning, “I wanted to go out.” Flight at that point mostly involved reading ur-American authors such as Sherwood Anderson, William Faulkner, and Thomas Wolfe. A year at the Newark campus of Rutgers didn’t satisfy the urge to get out from under, so he transferred to Bucknell, a liberal arts college in Pennsylvania with a postcard-perfect campus. Bucknell turned out to be conservative and not particularly welcoming to Jews, but Roth found lifelong friends and mentors there, including an affable professorial couple who encouraged him to keep milking the old neighborhood for comedy. He also started a campus humor magazine that hit its targets so accurately that a dean hinted at expulsion. He began to write fiction.

The next stop on the journey out was a master’s program at the University of Chicago, which Bailey calls a “demi-paradise” and Roth described, curiously, as a circling back to an idyllic past, but on a higher plane. Chicago, he wrote, was “like some highly evolved, utopian extension of the Jewish world of my origins, as though the solidarity and intimate intensity of my old neighborhood life had been infused with a lifesaving appetite for intellectual amusement and experimentation.” And then he met Maggie, who had lurid tales of childhood incest, and the getaway car hit a brick wall.

Much has been made of Roth’s woman problem. Feminists, among others, have called him a misogynist, and he heartily loathed them back, dismissing them as puritanical and blind to the complexities of emotional and sexual entanglements. He certainly liked to seduce and abandon. “As a rule, he thought there was a ‘two-year limit’ to sexual interest,” one ex-girlfriend told Bailey. He targeted his female students, and at least one old friend, Joel Conarroe, the chairman of the English Department at the University of Pennsylvania, actively procured them for him. At one point, Conarroe wrote a letter to Roth explaining how he bent the rules to let an attractive young woman into an oversubscribed class: “Having already turned scores of hysterical supplicants from your course I heard my mouth saying, all the while disbelieving what I heard, I’m sure Mr. Roth would enjoy having you (sly grin here) in his class.” Roth duly took the girl to bed.

Many of Roth’s female characters were as eager to gratify his male characters as he must have thought his students were. Even John Updike, no feminist, wrote in a review of Roth’s Zuckerman Unbound that the “engaging characterization” of Zuckerman’s mistresses was eclipsed by “Zuckerman’s babyish reduction of all women to mere suppliers.” If Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir of their marriage, Leaving a Doll’s House, had been published today, Roth’s reputation might have gone the way of Woody Allen’s. (Roth, a friend and briefly lover of Mia Farrow, loathed Allen, whom he seems to have regarded as a kind of cheap vaudeville version of himself. But there may have been other similarities that he didn’t want to face.) Bloom depicts Roth as supremely selfish, which was not unfair but could have been said of many male literary celebrities of the time; Roth looks positively chivalrous next to Norman Mailer. Bloom’s more explosive charges were, first, that Roth tried to kick her nearly grown daughter out of their home, which was true but may have had extenuating circumstances: the young woman despised Roth and—Roth thought—took a sadistic pleasure in manipulating her mother. The second accusation was that he twice made passes at a friend of the daughter. Roth laughed it off, telling the girl that her story was “pure sexual hysteria.”

I suspect that the source of Roth’s problem with women was that they were only intermittently real to him. Usually, they stood for something, which is not the same thing as being somebody in particular. Note that Zuckerman calls Maggie “something that,” not “someone whom,” Roth brought upon himself. Without seeming to notice how odd Roth’s words are, Bailey repeats his accounts of what drew him to this woman or that one. The attraction often had more to do with their background than personality or even sex appeal—although looks were a given. Roth seems to have perceived lovers and wives as objects of sociological desire. First came Maxine Groffsky, the model for Brenda Patimkin in Goodbye, Columbus, who personified the successful, assimilated Jew. Next was working-class Maggie, who hinted that her father, a drunk, had molested her and who divorced her previous husband on grounds of physical cruelty. She represented what Roth’s overprotected Jewish life had lacked till that point: “goyish chaos.” He thought she brought him closer to what Flaubert called “le vrai”—that is, unvarnished reality.

After Maggie, he took up with her opposite, Ann Mudge, an elegant socialite whose debutante party had been covered by Town and Country. Mudge’s father was an antisemitic Pittsburgh steel executive who also drank. In The Facts, Roth explains that he was drawn to Mudge because she, like Maggie, seemed “intriguingly estranged from the very strata of American society of which they were each such distinctively emblazoned offspring.” In other words, as different as they were, and despite their supposed alienation from their upbringing, each was a type. And a man is hard pressed to maintain an authentic connection to a type.

Roth also idealized Claire Bloom, at least at first. Though they became an item in 1976, he liked to say that he fell in love with her in 1952, when she costarred with Charlie Chaplin in Limelight, playing a suicidal dancer in need of rescue. Bloom remembers being mystified when he told her that he loved her, because she thought he had been treating her in a “strange and offhand manner.” But Roth had been staying up late to watch Bloom in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, in which she plays a sympathetic love object ensnared in Cold War machinations, and wrote a friend that he’d found “a great emotional soul-mate.” However rocky the early years and their benighted marriage, Roth was steadfast when it came to advancing Bloom’s career. He pushed her to do one-woman shows when jobs became scarce—wrote them, rehearsed them with her, even produced them. As Bailey writes, “Roth was especially doting to Bloom qua actress, and especially in the presence of their friends. ‘I have to go backstage now and see my little tchotchkala,’” he’d tell friends after performances. “Indeed, the more insightful of their friends detected a quality of playacting to the whole relationship.”

Roth’s women were ports of call in his voyage of self-escape. If he could add adultery to exoticism, so much the better. Subterfuge heightened the freedom, because losing oneself in a hidden liaison is easier—and sexier—than doing so in public. Roth itemizes the pleasures of adultery in Sabbath’s Theater. Mickey Sabbath’s happiest moments come during trysts in the woods with the buxom married Serbian innkeeper, Drenka, especially when she recounts the many sexual escapades she acts out with strangers for Sabbath’s voyeuristic pleasure. According to Bailey, Drenka was modeled on a Norwegian physical therapist he calls Inga Larsen (a pseudonym; the unauthorized Nadel tells us that she was actually a Swede named Maletta Pfeiffer). She, too, had serial affairs and regaled Roth with the details. Their relationship lasted an unusually long seventeen years, through most of his relationship with Claire Bloom. In his “Notes for My Biographer,” Roth told Bailey that he loved “the kick” he got from her “having a multiple self who behaves various ways in numerous lives” and “possessing an impressively lavish endowment of self-abandonment.”

But exogamy was not a lasting solution. The author of Goodbye, Columbus and Portnoy’s Complaint couldn’t shake the label “Jewish writer,” just as the polished celebrities, Zuckerman and the metafictional Philip Roth of Operation Shylock, are hounded by embarrassingly Jewy, reputation-damaging doubles: the sweaty would-be author Alvin Pepler (Zuckerman Unbound) and the grandiloquent identity thief “Philip Roth” (Operation Shylock). When Roth lived with Bloom in London and became all too aware of English antisemitism, both the coded dinner-party kind and the open statements of disgust, he grew a beard and responded as vocally and angrily as he always had to antisemitic slights. (Bloom was Jewish by birth, but by the time Roth met her, she had expunged all traces of her background from her life and tended to recoil from Jews who seemed seedily, identifiably Jewish, including Roth’s family.)

American Pastoral, the first and best of the three novels known as the American Trilogy, can be read as Roth’s concession that escape is impossible. The athletic star Seymour Levov, called “the Swede” because of his unusual, almost Nordic good looks and idolized by all of Jewish Newark, marries Miss New Jersey of 1949, the Irish Catholic Dawn Dwyer. They move to an estate in rural Old Rimrock, New Jersey, where Dawn decides to raise beef cattle. The Swede is as good a man as it is possible to be: a dutiful son who gives up a promising career in sports to run his father’s glove factory, a loving husband who subsidizes his wife’s money-losing business, a wonderful father. But his goodness can’t save him from catastrophe. His teenage daughter Merry, caught up in the revolutionary fervor of the 1960s, blows up the local post office and a beloved country doctor along with it, then disappears into the underground, leaving her parents’ lives in ruins. Bailey rejects the common view that the novel recants what Norman Podhoretz called the “pathological nihilism” of Portnoy’s Complaint. The novel repudiates nothing, says Bailey, claiming to channel Roth. Nor is the Swede the tragic hero punished for his all-too-human flaws; rather, he’s a victim of history, cut down because evil is random, striking the good and the bad alike. But Bailey’s reading is too generic, too universal. True, the Swede’s life is destroyed for no good reason, but the unreason is not unfamiliar. In the novel, Roth coined a now-famous phrase for the outbreak of madness that sweeps Merry away: “the indigenous American berserk.” The key word here is, I think, “indigenous.” No matter how blameless the Swede may strive to be, he’s still a Jew, and the country to which he tries to belong will somehow contrive to, in Borat’s catchy phrase, “throw the Jew down the well.”

We can deduce from Roth’s exogamous choice of Bailey as biographer that he hadn’t stopped worrying that Jewish particularism would box him in. Bailey wasn’t a bad choice. He’s the author of, among other works, a well-respected biography of John Cheever, like Roth, an acclaimed midcentury American novelist. And Roth was in a hurry; Ross Miller, a close friend whom he had asked to write the book that would refute Leaving a Doll’s House, had procrastinated for years and wasn’t acting like a man up to the job, or at least the job Roth wanted done. The new biographer had to be able to act fast, before Roth and those who knew him died.

Interviewing Bailey for the job in 2012, Roth asked the candidate to explain why “a gentile from Oklahoma should write [his] biography.” But Bailey’s non-Jewishness was not a deal breaker. Maybe Roth found Bailey’s skills so impressive that he didn’t care that Bailey had never written about a Jewish writer or dealt with Jewish themes. More likely, Roth didn’t want to be typecast. Bailey would have the authority to write of Roth that he was “among the last of a generation of heroically ambitious novelists that included such friends and occasional rivals as John Updike, Don DeLillo, and William Styron.” Roth would have been delighted to read Bailey’s kicker: Roth “stands the best chance of enduring.”

Philip Roth: The Biography is a straightforward, if pedestrian and overstuffed, account of a writer’s life and rise. It devotes nearly as much attention to book advances and sales, reviews and prizes, as to romances and feuds. Among the many unseemly things Bailey fails to be skeptical of is Roth’s obsession with the Nobel Prize, which he apparently felt he was owed. Bailey deserves credit for diligently identifying many of the individuals Roth turned into characters and wrestling a great deal of raw material into order. And yet, he’s no match for Zuckerman. What a reader wants from the biography of a writer as confessional as Roth is that it identifies his blind spots, sees what he couldn’t or wouldn’t see, debunks his myths. What didn’t Roth care to know, what did he withhold, what did he exaggerate, and why? Bailey doesn’t seem especially interested in those questions.

Bailey lacks a feel for Jews of Roth’s generation. In particular, it doesn’t occur to him to think about how they got out from under the weight of the past. They didn’t go in for family history the way Jews do now, and though Roth began locating lost relatives and soliciting their stories late in life, he never had more than a hazy understanding of previous generations. A well-researched account of his grandparents’ transition from the familiar but pogrom-ridden Galicia to the unknown wilds of New Jersey could have told us many things about Roth that Roth spent most of his life not finding out. The old country was not at all like a certain Broadway musical, as Roth observed, but what was it like for the Roths and his mother’s family, the Finkels? Bailey is as vague as Roth. He uses thirdhand sources and Roth’s own limited knowledge to reconstruct their corner of Galicia, the city of Tarnopol (Roth made it the surname of another of his alter egos). Bailey quotes Irving Howe about shtetl sociology here, offers an anecdote from Joseph Roth’s Radetzky March there, and serves up credulous generalities about Polish Jewish life: “Solace was found in ritual and piety. A good Jew’s life was finely regulated by 613 mitzvoth. . . . The law was embodied by rabbis.”

One such rabbi was Roth’s paternal great-grandfather, who “had a reputation as a storyteller.” Interesting! Roth’s maternal grandfather, Philip Finkel, dead before Roth was born, was, Bailey states matter-of-factly, “every inch the forbidding, Old World, Orthodox patriarch” who, to the horror of his American-born children, would “grimly” swing a live chicken on the eve of Yom Kippur. But much later, Roth heard from a cousin who had adored his “gentle” grandfather, and after all, a whole generation of immigrant grandfathers “shlugged kapparos,” some grimly, some joyously. So was the earlier Philip truly terrifying or an immigrant whose displacement had made his religious practices obsolete, therefore grotesque? The distinction matters when you’re talking about the father of a mother whose son never stopped writing about her. Philip Finkel probably was fairly scary, given that he and his brothers were said to have “crazy tempers.” Also interesting! Were the storytelling rabbis and angry men family legends or sources of intergenerationally transmitted character traits or both? Interesting again!

As it happens, “interesting” was a word with a specific meaning in Roth’s lexicon. In The Counterlife, Zuckerman declares that it “is INTERESTING trying to get a handle on one’s own subjectivity.” If a handle on subjectivity is what Roth was asking for, Bailey didn’t get it. Perhaps he didn’t have time.

Bailey has done future researchers a service, but his will not be the last word. Noodling around the Internet one day, I found the kind of demythologizing that Bailey doesn’t go in for. In 2018, the Stanford historian Steven J. Zipperstein, who is writing another biography of Roth, published an article in The Forward about a notorious 1962 symposium at Yeshiva University at which Roth was ambushed by outraged Jews. The traumatic experience was central to his vision of himself as a truth-telling outcast, and he wrote about it bitterly and often.

Zipperstein, however, got hold of a tape of the event. Roth was clever and self-assured, Zipperstein writes, “less victim than star of the evening. Time and again, the audience responded to him with laughter and applause.” Roth remembered that the moderator’s first question was whether he would have written the same stories in Goodbye, Columbus if he had lived in Nazi Germany. But according to Zipperstein, it was Roth who brought up the Nazis. Throughout the evening, Roth shone. He did not flee in disgrace. The incident, as Roth recalled it, was another source of productive fury, providing him “with a splendid foil, a packed, eager, inquisitorial audience bearing down on him,” says Zipperstein. It was one of his necessary fictions. Perhaps Zipperstein will be the biographer who makes the distinction between those and the interesting realities that lurk beneath them. I look forward to reading that book.

Epilogue

On April 20, 2021, the same day that my review of Philip Roth: The Biography by Blake Bailey went up on the website of this publication, news broke that Bailey had been accused of repugnant if not strictly illegal sexual misconduct with eighth-grade girls and of raping two grown women. The stories made you flinch: Bailey was said to have “groomed” twelve- and thirteen-year-olds when he was their teacher at a New Orleans middle school in the 1990s, meaning that he’d slathered them with fulsome praise, corresponded with them until they reached the age of consent, then dated some and allegedly raped another. Two years before these stories came out, a forty-three-year-old publishing executive had written Bailey’s original publisher, Norton, also charging rape. (Norton forwarded the email to Bailey.) Faced with these damning headlines, Norton announced that it would suspend promotion of Bailey’s book. A week later, Norton severed its relationship with him, pulling the audio and digital editions of the book and canceling all future print runs. A debate ensued about whether unpublishing a book for moral turpitude was just and proper, functionally censorship, or the start of a process that would make it too easy to unpublish authors, even those accused of lesser sins than Bailey. (That was what I worried about.) Then, in mid-May, another publisher, Skyhorse, which also acquired Woody Allen’s autobiography when his original publisher dropped it, signed up Bailey’s biography. The book was back on the market.

But the damage was done. Bailey had dragged Roth down with him, fairly or unfairly—and that guilt by association, it seems to me, is what we still have to deal with. I can’t stress emphatically enough that Roth was never implicated in anything like what Bailey has been accused of. So what are readers supposed to do with the news about Bailey? Should it change the way we read his biography? How about the way we read Roth?

Of course it shouldn’t change anything, and of course it changes everything. On the one hand, as we learned in freshman English, the work occupies a sphere separate from its author. To reduce literature, a category that can include nonfiction, to a mere gloss on its writer’s life and character is to blind oneself to the transformative powers of art.

That’s the theory, anyway. Reality is more complicated. For one thing, it’s hard to unknow what you know; the facts squat in your head like uninvited guests, kibitzing or nodding knowingly as the words come in. For another, some pieces of writing don’t rise to the level of art. Now that we’re better acquainted with Bailey (or think we are), we can read his biography as symptomatic, an unwitting revelation of unconscious forces he failed to master. A biography—and particularly the authorized biography of a living author, as Bailey’s was—is, among other things, the record of a collaboration that has either elicited new and unarticulated truths or left walls unbreached. What fascinates me about Philip Roth: The Biography are all the doors that Bailey and Roth together managed not to go through, the silences and self-justifications Bailey let Roth get away with.

Bailey’s fall from grace focuses our attention on the men’s attitudes toward women, and there is plenty to look at. Roth had a reputation for misogyny, both in life and in art, and Bailey obligingly sided with Roth in most of his disputes with women, especially his ex-wives. Bailey gave Roth, a man of festering grudges, the vindication he openly demanded at various points in his life, even if he later claimed to Bailey that he didn’t care about rehabilitation, only about being “interesting.” Roth had other blind spots, and Bailey cheerfully ignores those too. I addressed some of these in my review, though I couldn’t tackle all of them.

But what about Roth himself? Is he fatally diminished by Bailey’s misdeeds and curious incuriosity? I don’t think so. Bailey too shall pass. Other biographies will appear. Maybe they’ll be read; maybe they won’t. It depends on whether a writer now seen as one of the country’s most important continues to occupy that position or dwindles into a decontextualized artifact of a baffling past. I have faith that future generations will have the wherewithal to base that judgment on his work, or at least not on a series of sordid acts attributed to his biographer.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Not a Nice Boy

To every author who seemed too cautious—which was nearly every author he knew—Roth gave the same advice. “You are not a nice boy,” he told the British playwright David Hare. His friend Benjamin Taylor’s memoir is . . . nice.

When Everything Matters

Bellow on Roth on TV.

Bellow, His Biographers, and the “Quivering Schmucks”

Many authors have passionate readers, but few have drawn as many self-consciously nutty fans as Saul Bellow.

No Joke

Roth's new novel takes surprising turns on familiar territory.

Joe Kraus

What a terrific and thoughtful review. Having read the Bailey biography myself, I've been struggling over how to balance its earnest (and maybe illuminating) discoveries with its ambivalent presentation of Roth as Roth seems to have wanted. So much of the life is tawdry; what I want to reflect on is how Roth transmuted that tawdriness into ethical constructions. Shulevitz does a real service here, showing how to read this work as if it were another of Roth's own books -- and one of the more disappointing. That's not all a knock on Bailey who, as she says, pushes at times against Roth's structuring of the biography. It's just a useful framing of the successes and distortions of an ambitious project.

Maggie Anton

Apparently I was an early feminist because as a teenager I quickly gave up reading Roth's novels because I didn't like how they/he treated his female characters. I didn't know the word misogyny back then, but I recognized it when I saw it. Now, amazingly, Roth's biography has been canceled because of Bailey's sexual aggression towards women, some dating back to when he was an 8th grade teacher.