Not a Nice Boy

When he wasn’t writing fiction—day in, day out, for most of 55 years—Philip Roth was pondering fiction’s riddles. Why write? How can fiction compete with reality? And, most pressingly, why would anyone, for any reason, write cautiously? “Lower the boom,” Roth told the journalist James Atlas in the 1980s. Atlas was timid, a disease that Roth, in the decade since Portnoy’s Complaint, had successfully purged from his bloodstream. “I’m great at lowering the boom these days,” he wrote proudly to Atlas. “Wait’ll you read my book. Much boom lowering. Fuck ’em.”

To every author who seemed too cautious—which was nearly every author he knew—Roth gave similar advice. “You are not a nice boy,” he told the British playwright David Hare. “You should yield to the muses who know better than anyone, and stick to the wicked.” Roth’s friend Ted Solotaroff got a similar sermon. “The middle ground? FUCK THE MIDDLE GROUND,” Roth boomed at him. “You don’t stand on the middle ground, you crazy Jew bastard.” How could he even ask, Roth wondered:

Do you think becoming a Jew the way you have is the middle ground? Do you think all those kids and all those wives are the middle ground? There’s no middle ground for you, my friend, or for me. That’s why we’ve come as far as we have. The rest of them are back in Essex County straightening teeth.

The idea of Philip Roth straightening teeth in New Jersey might be one of the more terrifying counterlives Roth imagined for himself (never mind his patients). Yet it was understandable that Roth, raised in a strict household, where goodness and obedience were required, would understand inhibition. “Going wild in public is the last thing in the world that a Jew is expected to do—by himself, his family, his fellow Jews,” Roth wrote in 1974. The concept of goodness—duty, decorum, discretion—remained embedded in him, his bête noireas a writer.

With Roth gone, the problem of discretion has now been passed to Roth’s biographers, who, faced with the unseemly side of Roth’s character, have some decisions to make. To write honestly about Roth, to remove his fictional masks—Nathan Zuckerman, Alexander Portnoy, etc.—would be a feat of research and synthesis but also courage and ruthlessness. Will Roth be portrayed accurately for posterity? Or will he suffer the great and terrible fate of other literary idols: idealization, sanitization, glorification, his sharp edges sanded down for public consumption?

Two years after Roth’s death, we’re beginning to find out. Last autumn came James Atlas’s elegant memoir, Remembering Roth, which joined Claudia Roth Pierpont’s Roth Unbound, an airbrushed biography and tour d’horizon of Roth’s 27 novels. After these, the deluge: We’ll soon have a Yale Jewish Lives volume by Steven Zipperstein, critical biographies by Roth scholars Jacques Berlinerblau and Ira Nadel, and, later on, a full-scale biography by Blake Bailey. For Roth fans, it’s an exciting, nerve-wracking moment: Roth’s legacy is up for grabs, and the carefully constructed wall around his private life threatens to crumble.

Benjamin Taylor’s short, affectionate memoir knocks a few bricks loose, but it won’t do any lasting harm to Roth’s reputation. Taylor and Roth were intimates during Roth’s final decades—“he was my best friend and I his,” Taylor writes—yet this memoir comes laden with disclaimers, small preemptive apologies. It seems that Roth eluded Taylor: “He managed to figure out more about me than I ever could about him.” Roth was a dark continent, hard to know, and perhaps, on some fundamental level, unknowable. Taylor describes him beautifully: “a beguiling but remote citadel—august, many-towered, lavishly defended.”

“What I am struggling for in these pages,” Taylor writes, “is the fact of Philip as he was.” His book bears signs of a different struggle: between protectiveness and ruthless honesty. The war between duty and freedom—a perfectly Rothian dilemma!—isn’t resolved until the final, illuminating chapter.

The early chapters display both the virtues and hazards of being your subject’s best friend. Raised in the Weequahic section of Newark, an urban shtetl encircled by other ethnic enclaves, Roth was smart but no prodigy, a good boy with a stubborn streak. Many years later, Roth would reflect on “a penchant for ethical striving that I had absorbed as a Jewish child.” Here, we see the roots of Roth’s lifelong obsession with taboos and transgression. Indeed, Roth seemed to be reenacting an adolescent rebellion in novel after novel, flouting ethical limits, Jewish and otherwise.

Playing biographer, Taylor bestows upon Roth a cloudless childhood, a serene adolescence. “The emotional spectrum ran from contentment to extreme happiness.” This describes no one’s childhood, no one’s family, but Taylor persists in claiming so. “Happy at home and happy at school,” he writes blithely, quoting his subject. “The Roths were a sparkling example of what family life could be: the American dream coming true.”

Taylor seems to have taken perfect dictation from Roth, whose cheerful reveries are here rendered as fact. But a closer look at Roth’s private papers, which Roth scholars have been poring over for years, reveals a more complex reality. Herman Roth may have loved his son, but he was a difficult man, obdurate and unkind, who clung to his rigid certainties. “I knew I had to get away. I didn’t care where it was,” Roth once said. “I felt that if I stayed at home any longer I would kill him.” It seems Roth knew quite a bit about the family brutality in Portnoy’s Complaint. “I didn’t make that stuff up,” Roth told his friend Ross Miller in an interview. “That was real in the world I came out of.”

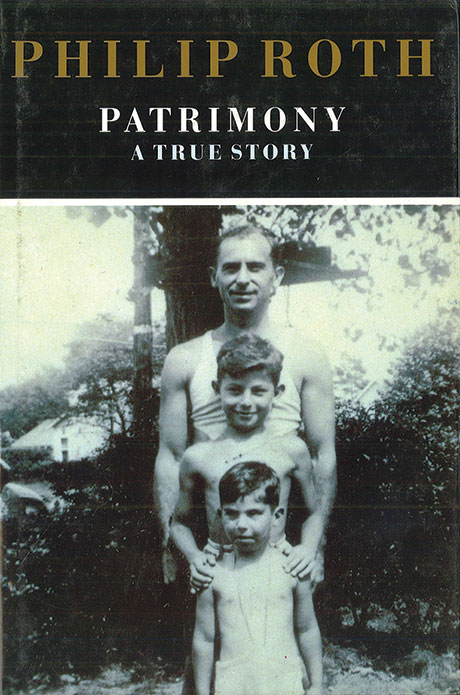

In recalling his father, Roth conveyed affection and devotion while betraying all the residual anger one would expect. Roth’s memoir Patrimony finishes with a dream—a nightmare, really—of Herman Roth’s rebukes: “in my dreams I would live perennially as his little son, with the conscience of a little son,” and his father would remain “the father, sitting in judgment on whatever I do.” What Roth retained long into adulthood were memories of weakness in the face of his father’s overwhelming strength.

About Roth’s mother, a loving but inscrutable woman whose passivity rendered her a bystander to father-son blowouts, we know somewhat less; in Roth’s memoirs, she’s curiously blank, more absence than presence. Still, if fiction is any guide—and with Roth, it usually is—the relationship was complex. “Jewish mothers know how to own their suffering boys,” says an aggrieved Zuckerman in The Anatomy Lesson. “The trouble with the human race,” says another character, “is rotten mothering.”

For all we don’t know about the Roths, we can be sure that adolescence was no picnic for young Philip. “The kinds of destruction loved ones can pour upon each other, wow!” he wrote a friend in 1959 while visiting home. “I don’t think anybody else in the world but the god damn Jews can kill each other so.”

It was this schizoid upbringing, tender yet claustrophobic, that Roth fled in 1950, lighting out for Bucknell University after a difficult freshman year at Rutgers. Roth’s sense of being an outsider, a Jew in gentile America, made Bucknell sound exotic, yet once there, Roth found a painfully sober campus, where a charming, anxious, outwardly confident Jewish boy must have stood out uncomfortably. In keeping with Bucknell’s “prevailing ethic of niceness,” Roth’s early stories were tame. This was Good Philip, the calm, rule-abiding son. “I wanted to demonstrate that I was ‘compassionate,’” he later wrote, “a totally harmless person.” Yet he must have sensed the Mr. Hyde scratching beneath the pious surface. Roth’s early satires, published in Bucknell’s student magazine, had bite, as did his fiction from that period (“when I was still kicking my family”). Roth was discovering his “talent for comic destruction,” he later wrote, and was “transforming indignation into performance.”

From that small, confining campus, Roth headed to the University of Chicago, where the main perks were friendship and literature—the sustaining forces in Roth’s life. Its arctic winters aside, Chicago was paradise, and Roth spent a blissful year reading for a master’s in literature (he enrolled in a PhD program but quickly washed out). While there, he discovered Henry James, absorbing the Master’s lessons—“Dramatize! Dramatize!”—and a hint of high-class refinement. Well into his fifties, Roth’s diction was peppered with Jamesianisms: “quite,” “you see,” “as it were”—everything but “hung fire.” The effect was charming—a Newark Jew with a touch of Oxford don to him.

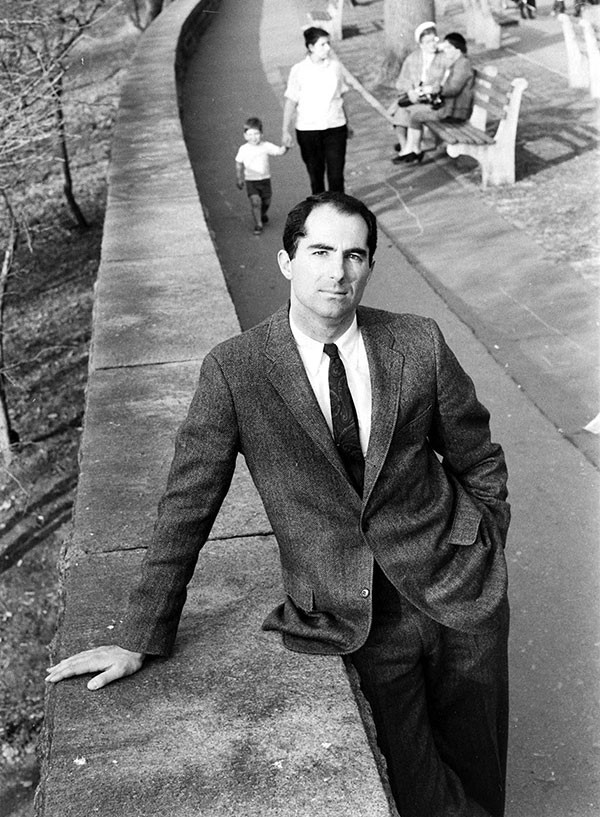

Roth pursued his ambition zealously these years. Meeting The New Yorker’s editor, William Shawn, he showed him “Conversion of the Jews,” boldly requesting publication. (Shawn declined, in his meek-yet-assertive way, suggesting that Roth might consider himself too avant-garde for Eustace Tilley’s decorous pages.) While absorbing his share of rejection, Roth also lucked out by having stories plucked from slush piles at Commentary and The Paris Review. Roth had one eye on his mailbox and one on a calendar. “I shall be twenty-five next week and stouter, and I feel a tiny knife in my side as I race to be a boy wonder,” he told his editor in 1958. The sprint ended in 1959, when Goodbye, Columbus came out in hardcover.

Publication marked round two of what a critic later called “Certain Hyperanxious Jews v. Roth.” His depictions of Jews acting badly—cunningly, selfishly, tribally—angered plenty of Jewish readers, but the critics who mattered—Bellow, Howe, Kazin—bestowed their blessings. “Goodbye, Columbus is a first book, but it is not the book of a beginner,” Bellow gushed in Commentary; Roth was “skillful, witty, and energetic and performs like a virtuoso.” At 26, Roth was anointed; the following year, while in Rome, he won the National Book Award, the grand news arriving via telegram.

By then, Roth had developed the fanatical writing habits that would sustain him for a lifetime. A slow but determined worker, Roth felt his way forward blindly, producing reams of unusable manuscript on the way to a finished draft. From then on, his books wouldn’t get written so much as accumulate, a drip, drip, drip of prose, the opposite of Updike’s propulsive geyser.

“Whom the Gods wish to destroy they first call promising,” Cyril Connolly once wrote, and for a while, this applied to Roth, whose next two novels were polished, decorous, and dull, written to impress the ghost of Henry James. By that point, Roth had married his Chicago girlfriend, Margaret Martinson. A blonde, divorced, non-Jewish mother of two, she might have been cast from a Jewish mother’s nightmare, and one suspects that was part of her attraction. (Herman Roth accepted the union grudgingly but had no qualms about telling his son that his wife dressed “like a piece of shit,” insisting he buy her a new coat and move to a better apartment. “I have just about had as much as I can bear,” Roth told Solotaroff.)

The marriage was brief, but Roth got plenty of material out of it. Taylor repeats Roth’s “lurid” account from My Life as a Man, where Roth cast himself as the blameless victim, duped into marriage by an emotionally unwell woman. “She was Philip’s bighearted mistake,” Taylor agrees. Perhaps, but the reality was probably more complex. In letters to friends, Roth described an affectionate but stormy marriage, one with ups and downs, but hardly the grand catastrophe he later depicted. Regaining his critical wits, Taylor speculates that Roth’s serial philandering might have pushed Margaret over the edge. What’s for certain is that things were relatively calm until 1963, when all hell did apparently break loose and both sides were driven crazy. “I might have killed her,” Roth told Solotaroff, having fled the marriage and the country after their final blowout. Margaret had wanted him arrested, “But this cunning Jew left three days before announced, and saved his life.”

The defining event of Roth’s literary life came in 1969: Portnoy’s Complaint. The grand explosion was preceded by several smaller blasts: the publication, in various journals, of several eye-catching excerpts. After being rejected by The New Yorker, “A Jewish Patient Begins His Analysis” ran in the April 1967 Esquire; another chapter, “Whacking Off,” appeared in, of all places, Partisan Review and fetched Roth the princely sum of $150. The book was scandalous before it came out. “I understand I am on the brink of becoming a Celebrity,” Roth wrote the poet Josephine Herbst before publication. He had no idea.

The book’s shocking lewdness and wild comic abandon made it an immediate sensation. This was something new for American readers, but not for Roth—he’d been vamping for friends, doing outrageous shtick, since college, while also spilling his guts in therapy. From those fissile materials—wild comedy and frank sexual confession—came Alexander Portnoy, an anxious, neurotic, repressed, completely unfiltered boychik being devoured by inner conflict. “Enough being a nice Jewish boy, publicly pleasing my parents while privately pulling my putz!” Portnoy cries. The Rothian psychodrama of goodness vs. naughtiness produces a towering rage that is projected at women, his parents, and, famously, the family dinner. With Portnoy, Roth triumphed over niceness in grand fashion: “Do me a favor, my people, and stick your suffering heritage up your suffering ass.” Hard to call yourself a nice Jewish boy after writing a sentence like that.

Portnoy’s Complaint changed Roth’s life. All at once, he was deluged with fan mail, media requests, propositions. There were jokes on the Tonight Show (Jacqueline Susann: “Philip Roth is a good writer, but I wouldn’t want to shake hands with him”). “I don’t think I can communicate . . . what it is like,” Roth told Solotaroff, pining for Bernard Malamud’s quiet life (“I should be so lucky!”). Too late for that. Portnoy’s Complaint sold over 400,000 copies, surpassing The Godfather as 1969’s bestseller. Roth celebrated his breakthrough by fleeing New York City for the Yaddo retreat in Saratoga Springs, New York.

The experience of life changing suddenly, of losing control of his reputation, changed something in Roth; from then on, a more guarded, suspicious Roth would appear in interviews. When recalling his former life—“before fame and riches struck”—Roth sounded battered and wistful. Now, he was recognized and caricatured. Publishers pushed him as a scandalous author. “They must stop this trading on Portnoy’s Complaint . . . And stop it now,” he wrote a British editor 13 years later. He couldn’t be an “author” constantly doing promotional stunts. “This is all a terrible perversion of writing, and it’s gotten to me in a big way,” he told Claire Bloom, his longtime partner, in a letter. “It’s not for me, never was, and that’s that.” By that point, Roth had abandoned New York City for a secluded country house in Connecticut—his own personal Yaddo, he said. From then on, Roth revealed himself mainly in novels, teasing readers with characters who resembled Philip Roth. Fiction provided him cover—plausible deniability. “I can only exhibit myself in disguise,” says Zuckerman in The Counterlife. “All my audacity derives from masks.”

In 1969, no one could have foreseen the course of Roth’s career, yet one might have guessed, already, that a serene life wasn’t in the cards for him.A certain restlessness was endemic to Roth’s nature. Finding himself bored or stuck, he hustled along to fresh scenery. Not that he ever stayed put: “I always seem to need to be emancipated from whatever has liberated me,” he once said, suggesting an unconscious preference for turmoil, a quota of tzuris he needed to meet. At the same time, Roth craved stability, and he seemed to veer between those extremes. “How much peace am I made for?” Zuckerman wonders in The Facts, “how much more of that intense and orderly domesticity that I once craved can I afford to take?”

Those twin urges, pulling him in opposite directions, guaranteed plenty of turmoil, which provided superb material for fiction. Tumult served him well. So did anger and contempt. “A writer needs his poisons,” Roth told The Paris Review in 1984. (He told Taylor the same: “A writer needs to be driven round the bend.”) Those poisons may have damaged the person, but they often inspired the writer. “You actually like to take things hard,” says Zuckerman in The Counterlife. “You can’t weave your stories otherwise.”

There was certainly no lack of conflict after Portnoy’s Complaint. To the historian Gershom Scholem, Portnoy was dangerous—“the book for which all antisemites have been praying,” he wrote in Ha’aretz. It was Irving Howe—another sort of father, harsh and stubborn—who delivered the coup de grâce. Portnoy was tasteless, a collection of cheap gags, not real literature. “The cruelest thing anyone can do with Portnoy’s Complaint is to read it twice,” Howe wrote in Commentary, a blow that landed hard. The problem, Howe said, was Roth’s “thin personal culture,” which couldn’t nourish serious literature. Absent that, he had only “egocentrisms” and “eccentricities.”

Would the criticism have stung so badly if there wasn’t some truth to it? Likely not. While taking it to heart, Roth also lashed back in print, thus mixing the pleasure of writing with the joy of revenge. “I’m a petty, raging, vengeful, unforgiving Jew, and I have been insulted one time too many by another petty, raging, vengeful, unforgiving Jew,” he wrote in The Anatomy Lesson, casting Howe as Milton Appel, a sententious bore with a vicious streak (“A head wasn’t enough for Appel; he tore you limb from limb”). That round went to Howe, but Roth was an able counterpuncher, eager to battle.

Other antagonists were lining up, replacing the castrating critics, cunning ex-wives, and angry Jewish leaders who stalked Roth’s imagination. Now there were shouts of “misogynist,” a label Roth angrily rejected but never managed to shed. Though hardly so flagrant as Bellow (“You women’s liberationists! All you’re going to have to show for your movement ten years from now are sagging breasts!”), Roth’s talent for angering feminists was considerable. Early on, his female characters tended to be enemies, not stand-ins for womankind, but far too many were simple lust objects, there for the delectation of Roth’s alter egos. By the time the Village Voice ran a cover story accusing Roth of misogyny (he was lumped with Bellow, Mailer, and Henry Miller under the headline “Why Do These Men Hate Women?”), Roth’s reputation as a male literary chauvinist was cemented.

Roth turned this, as he turned nearly everything, into material. “Can you explain to the court why you hate women?” a feminist questions “Philip” in a mock trial in Deception. Arguing pro se, Philip snaps back, “Why do you, may I ask, take the depiction of one woman as a depiction of all women?” Roth’s public posture—prickly and defensive—concealed a more thoughtful, conflicted attitude. Privately, Roth admired aspects of feminism. “The women are making our lives easier (by pressing, as they are) and making us smarter,” he wrote Solotaroff in 1972, sharing his hope that women would write about masculinity (“a woman would have the best vantage point”). At the same time, feminist discourse drove him crazy. How could he stand “such militance, so much agitprop rhetoric, so much outright propaganda,” he wrote the poet Honor Moore in 1973. If women were so strong and confident, why did they need uplifting slogans?

Roth’s relationships with women ran a wide gamut, romance being the other arena (besides writing) where he felt completely unconstrained. Roth’s girlfriends tended to be stable, generous, and accepting—if Roth was already married to literature, so be it. When these “wife-candidates” moved on, Roth went in for numerous affairs, charming prospective lovers with intense, flattering attention. In conversation, he could be aggressive—scrutinizing, interrogating. “The speed and power of seeing was such that it seemed pointless trying to defend yourself against it, or to object when the play got rough,” one girlfriend, Janet Hobhouse, remembered. To be caught in Roth’s klieg lights was unnerving: “he always listened like someone decoding, sensing, processing vulnerability, a place to enter, overpower.” Taylor, who got an earful about Roth’s sexual exploits, hails Roth as “an ardent lover and a sexual anarch.” The anarchy seems pretty mild, however—mostly adultery, nothing too outré or perverse. He knew little about sexual “proclivities,” he told Janet Malcolm; reading about kinky stuff made him “feel like a guy from Wichita, or even Newark.” That Roth remained single after 1995 was more accident than plan. According to Taylor, Roth proposed to any number of girlfriends he was infatuated with or feared losing, feeling both sorrow and relief when they said no.

Roth may have enjoyed adultery for its excitement, novelty, and the pleasure of being admired, not to mention mischief (Taylor notes that he was “not averse to cuckolding inattentive husbands,” sidestepping, with a clever phrase, the turmoil he surely caused in many marriages). But nothing in Roth’s life was as central as writing. Nothing else offered the pleasure, hard-won satisfaction, or outlet for his outsize energies, angers, and ambitions. “I have to feel anchored to work,” he told Claire Bloom in 1976. Writing meant freedom—“Shame isn’t for writers. You have to be shameless”—as well as refuge from life’s painful vicissitudes. “I’m huddled in my studio, where I really wish I lived,” Roth wrote Updike in 1996; “it’s all I ever wanted, more or less.”

At the same time, writing was hard, lonely business, utterly exhausting. During bad stretches, Roth joked about quitting: He would become a doctor. He’d open a delicatessen in Connecticut, “Cornwall Corned Beef,” or work in a liquor store. “I am thinking of defecting to Russia,” he told Updike, where he’d never have to read reviews again. “Any job but this one!” he told James Atlas.

Roth’s hymn to the writer’s life—its pleasures, miseries, hazards, and seductions—was his lapidary 1979 novel, The Ghost Writer, a masterpiece in the Henry James mold. Here, young Nathan Zuckerman, literary apprentice, visits his idol, E. I. Lonoff, to observe the master’s lifestyle. “Purity. Serenity. Simplicity. Seclusion,” Zuckerman thinks, deciding that literature is what matters—“the grueling, exalted, transcendent calling.” Yet Nathan is tormented by his Jewish critics, those unappeasable elders, whose approval and forgiveness he covets. Instead, he gets censure—“Can you honestly say that there is anything in your short story that would not warm the heart of a Julius Streicher or a Joseph Goebbels?”—and stays imprisoned in the role of needful, sensitive son.

As with Zuckerman, so with Roth. He had sought “the end of being a literary son,” he told Solotaroff, and believed he had achieved it: “Every morning when I come out to the studio, I write in big letters on the top page of my yellow pad, ‘WHO CARES?’” Someone who needs to write “Who cares?” is probably not beyond caring, and Roth’s mission to ignore criticism—“throwing off the world of our literary fathers for good”—certainly continued as he wrote The Ghost Writer.

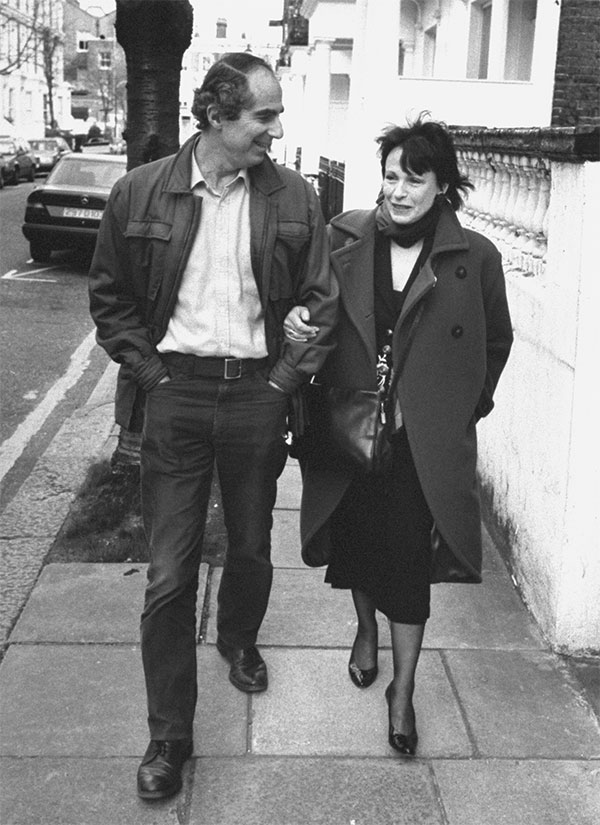

Roth had completed the manuscript in London, where he now spent half his time, having settled into a long-term relationship with Claire Bloom. At first, London was a tonic, the city working its magical charm on him, rewinding the clock to pre-Portnoy times. “Nobody knows who the fuck I am,” he told Joel Conarroe, a friend back in the States. “I swim anonymously, eat anonymously, go to the theater anonymously, and yet I secretly know who I am. Nice.” For a fleeting period, Roth was cheerfully social, but the more familiar London became, the more its charms came to seem like drawbacks. Conversation was stilted. London was dull and dreary—“it’s all garbage and rain,” he moaned to Atlas. Worse was the genteel antisemitism of upper-class Londoners, something Roth could never abide. England’s bien-pensants disliked Israel; a haughty distaste for Jews was common, even in public. In her memoir, Bloom recalls a time when Roth confronted a woman in a restaurant, called her a “scumbag,” and stormed out.

By the late 1980s, Roth was through with London. “This is truly the most wretched of civilized places,” he told his editor, David Rieff. Back he came to New York, once more liberated. “My re-entry has been exhilarating,” he wrote Updike, swearing he’d never leave home again. The Upper West Side was a balm and a delight. “Jews with appetite. Jews without shame,” he wrote in Deception. “Complaining Jews who get under your skin. Brash Jews who eat with their elbows on the table. Unaccommodating Jews, full of anger, insult, argument, and impudence.” Home sweet home.

The fear of repeating himself, of writing the same book over and over, weighed on Roth as much as any novelist. “I am running out of styles,” he told Atlas in 1982. The satirical novel. The Jamesian novel. The Jewish family farce. The novel about novelists. Having tired of self-analysis (“the solemn undertaking I call ‘understanding myself,’” as one character puts it), something seemed to shift for Roth in the early 1980s. “Other people,” Zuckerman thinks in The Anatomy Lesson. “Somebody should have told me about them a long time ago.”

That spirit of curiosity, of horizons expanding, infuses The Counterlife (1986), Roth’s greatest work from that decade. In a sense, it was vintage Roth: There was lots of chatter (“the purest form of eros . . . that endless, issueless, intimate talk”) and wicked comedy. The earlier theme of doubleness, the divided self, undergoes a subtraction: Here, the problem is hollowness. “I am a theater and nothing more,” says Zuckerman, declaring that “I, for one, have no self.” The book’s postmodern gimmicks—characters die, return to life, have different adventures—drew plenty of attention, but the main surprise was a rich new subject: Israel.

Roth had been fascinated with Israel in the 1960s, when a conference brought him to Jerusalem; he rediscovered Israel in late 1984. “Israel is the place to give your curiosity a workout,” he wrote Solotaroff in a rare quiet moment. Roth toured widely, a glutton for experience, interviewing everyone from authors to NGO workers to ordinary Israelis. It wasn’t the Israel of popular myth—the plucky young country with an infallible army—but the actual Israel, seething, quarrelsome, self-questioning, that inspired Roth’s affection. “I’m only back two days and feel like taking the plunge again soon,” he wrote Solotaroff. “Each time you go out further and see more and are further astonished.”

The Counterlife became the vessel for Roth’s impressions, his attempt to capture “all the turbulence in the modern Jewish soul” in a different kind of novel. Instead of an anxious, beleaguered narrator, we have a wondering one, a listener, not a talker. The novel’s babel of voices included left-wingers but also proud and ardent Zionists. In Israel, Jews can lead “a life free of Jewish cringing, deference, diplomacy, apprehension, alienation, self-pity, self-satire, self-mistrust, depression, clowning.” Like his creator, Zuckerman is energized by a place where “argument is enormous” with “everything italicized by indignation and rage.” Israel was a country after Roth’s own heart.

Roth’s fascination spilled over into a second novel. Operation Shylock, published in 1993, approaches a third rail and hugs it for 399 pages: Jewish power, Arab rage, and the intractable Middle East conflict. “Exterminating a Jewish nation would cause Islam to lose not a single night’s sleep, except for the great night of celebration,” one Israeli declares. “Nine tenths of their misery they owe to the idiocy of their own political leaders,” says another. It’s a complex, prismatic portrait with something to challenge and infuriate everyone. Which is the real Jewish capital, Israel or New York? “There’s more Jewish heart at the knish counter at Zabar’s than in the whole of the Knesset!” a character exclaims.

In this novel of voices, one voice was curiously absent: Roth’s. That was deliberate; Roth went to great lengths to conceal his personal politics. On one hand, he credited Israel with boosting Jewish American morale. The Jews had no future in Europe, he thought, making Israel utterly necessary. On the other, he was amused and bothered by the settler movement, annoyed by a religious zeal he couldn’t relate to. The Counterlife calls militant Kahanism “the logical step after Begin,” and Roth felt similarly. “Begin’s attempt to fuck up the establishment of the state back in 1945 are equal really to his almost destroying it in Lebanon,” Roth told David Rieff. Returning home in 1988, Roth quarreled with his right-wing father over whether the Intifada was a violent antisemitic pogrom. Roth pressed his case to others, drawing a friendly rebuke from Cynthia Ozick, who considered him naive. “Your father is right,” she chided him, taking up the subject again two years later. “He’s even righter now than he was then, if you’ve read Hamas leaflets.”

Roth had high hopes for Operation Shylock, hopes that were quickly dashed by mixed reviews. “His characters seem to be on speed, up at all hours and talking until their mouths bleed,” John Updike complained in The New Yorker. He wasn’t the only critic reaching for aspirin. “One quickly wearies of a prose that is always yammering or orating like this, that is always going into cardiac arrest,” James Wood griped in The New Republic. It was a perennial criticism, one generally made by non-Jewish critics: Roth’s novels were migrainous gabfests. If that was true, it was also deliberate. “You speak speak speak,” a character says in Operation Shylock, all but clutching his temples. “Speak speak speak speak speak speak.”

Roth was wounded by the criticism, especially Updike’s; in the ensuing months, his mood darkened considerably. Roth was no stranger to depression, having suffered two serious episodes in 1974 and 1987. “I had to crawl out of bed in the morning on my hands and knees,” he told Atlas, describing how, with the help of antidepressants, he slowly regained functioning. The second episode, an organic depression worsened by the sleeping pill Halcion, was arguably worse. “I’ve misplaced everything, my life included, during these past few months,” he told Janet Malcolm while in the thick of it.

Roth’s final serious depression was amply chronicled in Bloom’s unsparing memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House; their grim and anguished correspondence is a remarkable record of the marriage’s collapse. After weeks of distress, Roth landed in Silver Hill Psychiatric Hospital. When Bloom attempted to help, Roth rebuffed her; in a therapy session, he poured out 17 years of grievances, her high crimes and misdemeanors, building a case for divorce.

“No one can leave anything without hating it first,” Roth once wrote, and indeed, Roth apparently needed to villainize Bloom before leaving her. (Bloom, no idiot, saw what was happening: “Philip, you’re demonizing me. You’re turning me into Maggie”—Roth’s first wife.) Though clearly suffering, Roth also seemed to choreograph his exit, driving Bloom crazy (then accusing her of insanity) and forcing her away (then accusing her of neglect). In letters to friends, Roth repeated accusations of betrayal and abandonment, but Bloom’s letters tell a different story: a wife repeatedly, desperately attempting to rescue her husband only to be thwarted and rejected by him.

When the dust settled, Roth was free again, living comfortably in New York City. “The upshot of the experience is that Claire and I are living apart,” he told Solotaroff. It was unfortunate, he added, but “absolutely necessary for me.”

Liberated, Roth repaired to Cornwall and began one of the great third acts in American literature. “I’m writing my wicked book much more quickly than I had imagined. I love mischief,” he gushed to Janet Malcolm. That book would be his rude classic, Sabbath’s Theater, a nasty, scabrous novel in the tradition of Céline. The former puppeteer Mickey Sabbath is unwashed, untamed, floridly obscene, shameless. Put on trial for disorderly conduct, he scoffs, “I am disorderly conduct.” With Sabbath’s Theater, Roth got deep into the muck, dragging the reader down with him. “For a pure sense of being tumultuously alive, you can’t beat the nasty side of existence,” Sabbath declares. Roth reveled in the book’s success, beaming over positive reviews and a National Book Award.

Having unleashed mayhem, Roth swerved sharply with American Pastoral, the tale of a wholesome, clean-cut everyman, Swede Levov, whose profound decency proves to be an Achilles’ heel. Here, Roth’s subject was history with a capital H: the 1960s radicals, embodied by a Weatherman-like extremist. “How could she ‘hate’ this country when she had no conception of this country?” her father wonders. The author seems to agree: Radicals aren’t brave; they’re just mad at their parents. In response, several Roth scholars rejected the notion that Roth had turned conservative. This is true—he was always somewhat conservative, if not politically then temperamentally, disdaining the counterculture and radical chic. American Pastoral was embraced by conservatives and nearly everyone else, snaring the Pulitzer Prize.

Two more novels followed in quick succession. The Human Stain, set during Clinton’s impeachment, vented Roth’s disgust with political correctness, and I Married a Communist reoffended conservatives while exacting revenge on his ex-wife. In the first book, we meet Coleman Silk, a character partly based—Roth’s denials notwithstanding—on Anatole Broyard, a black literary critic who passed as white. Roth was fascinated with Broyard’s “seductive charlatanism” and his “genius . . . for elaborate mischief,” he told Updike, giving those same qualities to Silk, a classics professor. The man’s tragic fate, after years of passing, is to be fired for a racially insensitive remark. Brought low, he’ll soon fall lower, into a hell of judgment and persecution. A similar humiliation awaits Ira Ringold in I Married a Communist after his wife, a shallow British actress, outs him, smashing his career and reputation in one malicious blow.

For all their roiling energy and dramatic collisions with history, the books’ keynote was resignation. “This is human life. There is a great hurt that everyone has to endure,” Sabbath sighs, while Zuckerman despairs of ever getting people right: “It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong . . .” Youthful illusions topple one by one. Whereas Portnoy craved freedom, his elders, humbled by experience, know how constrained our lives are. Everything conspires against us: the past that isn’t past; the hazardous present, where our enemies live; our rickety, failing bodies, always betraying us or about to; the cruel and indifferent cosmos. We are “destined to lead a stupid life,” says Sabbath, pondering our folly and bluster, “because there is no other kind.”

These parables of suffering marked new territory for Roth, who had withdrawn into rural seclusion in Connecticut. The Human Stain reads like a plea for mercy, almost childlike in its earnestness. Why can’t humans be gentler? Why must we shame and destroy one another? Each book seemed to speak to Roth’s emotional condition at the moment. “Why don’t you have the heart for the world?” a character asks Zuckerman in I Married a Communist, although he seems to know the answer: “You don’t realize how much plain old misery can be backed up inside a titanically defiant person who’s been taking on the world and battling his own nature his whole life.”

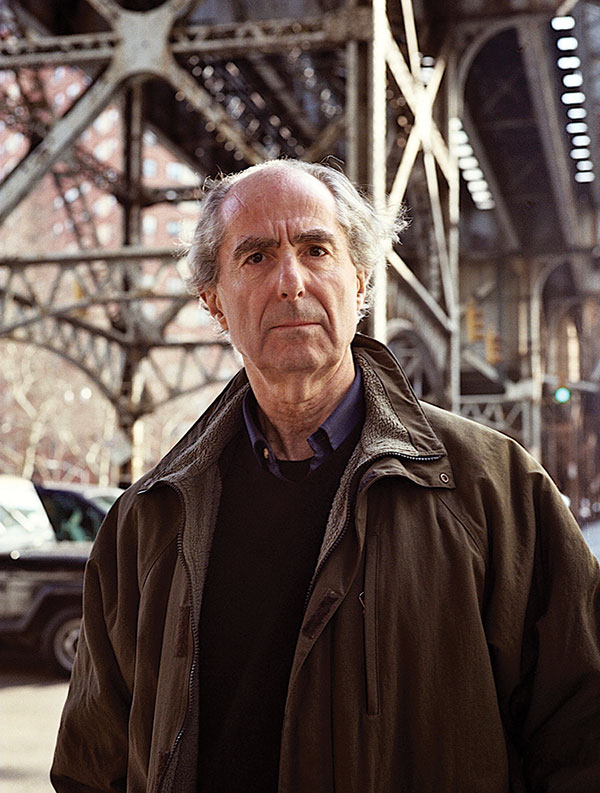

Roth’s final years, difficult ones, are captured well by Taylor, who met Roth in the mid-1990s and gamely supported him through various medical and personal travails. Taylor’s prose can be choppy but at times achieves a wonderful directness. “He was fully half my life. I cannot hope for another such friend,” he confesses. There’s a modest charm to this memoir, especially the sections set after 2000, when losses mounted. Roth’s generation was shrinking; the roll call of departed friends included William Styron, Ted Solotaroff, and several Bucknell classmates. Saul Bellow died in 2005, a harsh blow for Roth, who found the funeral service wrenching. Though Roth had stopped speaking to Updike in 1999, he took no pleasure in having outlasted his great contemporary when Updike died in 2009.

The promethean Roth—seething, lusting, ranting, fulminating—seemed to vanish after The Human Stain, ceding his pen to the somber, death-haunted Roth, whose final quartet of short novels (Everyman, Nemesis, Indignation, The Humbling) offered a head-on reckoning with death. “Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre,” Roth wrote in Everyman, using the pared-down late style he had perfected. Aware that his powers were waning, Roth announced his retirement in 2011. “The battle is over,” he wrote on a Post-it note near his computer.

But appearances, as ever, were misleading. Taylor confirms that Roth not only continued writing after his “retirement” but wrote fiercely and angrily. “He couldn’t stop litigating the past,” Taylor writes, revealing that Roth penned several lengthy screeds about old enemies. One such project, wisely scrapped, was Notes to My Biographer, a “point by point” refutation of Claire Booth’s memoir (“whose publication Philip counted among the worst catastrophes of his life and credited with his failure to win the Nobel”). Another was Notes on a Scandal Monger, intended to punish Ross Miller, his feckless biographer, whose failure Roth took for malicious neglect.

“The appetite for vengeance was insatiable,” Taylor writes. “Philip could not get enough of getting even.” In that respect, Roth remained himself, though in more profound ways too. His mania for privacy never lessened. Roth was “deeply secretive about his mental breakdowns,” Taylor writes, suggesting the burden of shame Roth carried with him for decades. This may not be shocking (“Shame in this guy operated always”—The Counterlife), but to have it confirmed is still jarring. Portnoy feared headlines “revealing my filthy secrets to a shocked and disapproving world.” Roth feared that his physical frailty and emotional instability would be revealed. That’s just what Taylor does, shedding restraint in his candid final chapters.

By removing at least some of Roth’s masks, Taylor both enlarges and complicates our conception of him, yet this memoir of deep friendship feels curiously shallow. Having promised to present Roth “without reticence,” Taylor finishes with a disclaimer: “This book has been a partial portrait, of course.” Taylor is gentle and discreet—fine qualities in a friend but bad ones in a memoirist. He writes vaguely that “torment about rectitude plagued him” but doesn’t describe that torment in any detail. (Roth abhorred generalities; Taylor relishes them.) Roth’s paranoia is treated as a quirk, not a central quality, and his various selves are often simplified or ignored. Far too often, Roth is portrayed as onething, when in fact he was nearly always multiple, a bundle of conflicting impulses and appetites.

When not spilling Roth’s secrets, Taylor is fulsome, bathing Roth in adoration. “To talk daily with someone of such gifts had been a salvation,” he writes, crowning Roth “the best American novelist of his generation, our likeliest candidate for immortality.” That may indeed be posterity’s judgment, though it would be disappointing if Roth’s bitterest pills were swallowed like warm broth by future generations. Lionel Trilling said that literature should be like a howitzer; Kafka called it an ax cracking “the frozen sea inside us.” Roth undoubtedly agreed about fiction’s powerful, even assaultive, force. In 1982, he wrote to Solotaroff, thanking him for flattering comments about The Anatomy Lesson. “If you think I’m like Koufax the day we saw him strike out Mantle three times, that’s good enough for me,” Roth replied:

That’s the power I wanted, kid, and the cunning, and the detached meanness. I wanted the roughness in this book. And that’s probably just what it was like throwing against Mantle: rough. Bravo for me.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Letters From Chicago

One of the many pleasures of the recently published Saul Bellow: Letters is how it reacquaints us with Bellow's wry, poignant, infectiously erudite voice. This is all the more surprising because he wasn't, or at least so he insisted, a natural-born letter writer. As in his literature, Bellow's language is so stunning that one wonders whether he was writing to both his correspondents, and to readers like us.

No Joke

Sigmund Freud loved Jewish jokes and for many years collected material for the study that would appear in 1905 as Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. An excerpt from Ruth Wisse's new book No Joke: Making Jewish Humor.

When Everything Matters

Bellow on Roth on TV.

Disgruntled Ode

For a young daydreamer, nothing is more beautiful than the unspoken, which becomes the focus of desire. And the Jewish unspoken of my childhood was so vast that, within it, the imagination could reach near-spiritual proportions.

Carlo Pinotti

Great article summing up Roth’s achievements. He should have received the Nobel Peace Prize!