When Everything Matters

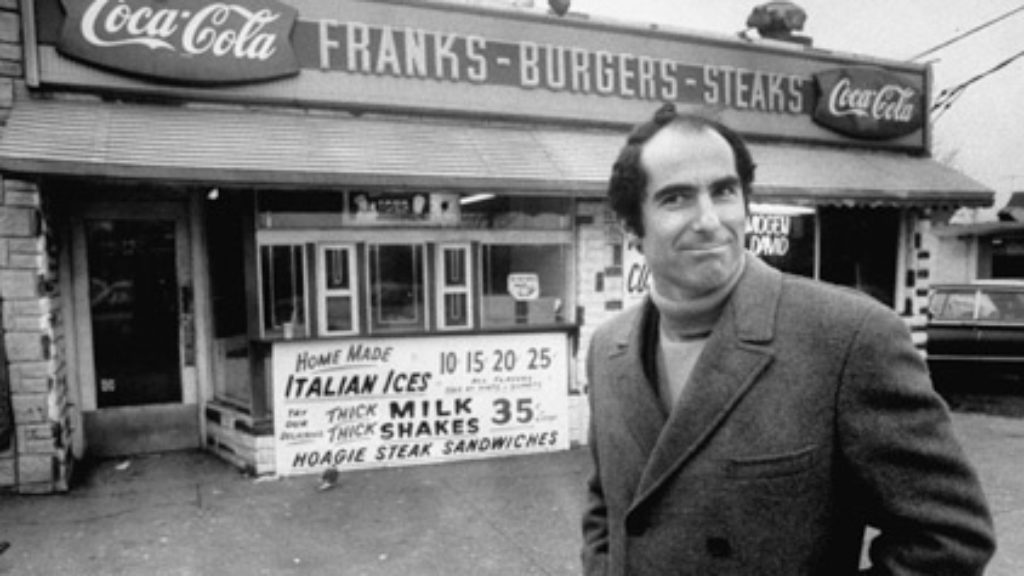

“Fear presides over these memories, a perpetual fear.” A couple of weeks ago, I was asking myself if it was a good idea to teach my students a book that begins with this sentence at this particular moment. And now, as we move toward what’s being called “self-isolation,” do I want to recommend a six-part HBO series based on this Philip Roth novel, The Plot Against America? Yes and yes.

The television series isshot through with the same terror as the novel—celebrity aviator and Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh defeats FDR in the 1940 election and a simmering, now sanctioned antisemitism comes to a boil. Both the novel and the series take us inside one small, unremarkable Newark Jewish family and show us what ordinary people do when everything falls apart.

The writers and executive producers of the miniseries, David Simon and Ed Burns (who collaborated to great acclaim on The Wire), have taken Roth’s least sexy book and created sizzling television. The novel’s sober narrator, nine-year-old Philip, gave us impressions gathered through the frightened and often uncomprehending eyes of a child, while interjecting the awareness of the adult Philip, so that mature reflection overlaps seamlessly with childhood confusion.

In the series, we often encounter the terrified gaze of the young Philip (memorably played by Azhy Robertson), but the story is not seen exclusively through his eyes; it doesn’t belong to him in the same way. In the novel, Roth often decants his genius as a writer into the little boy’s reflections:

Their being Jews issued from their being themselves, as did their being American. It was as it was, in the nature of things, as fundamental as having arteries and veins, and they never manifested the slightest desire to change or deny it, regardless of the consequences.

Does this sound like a kid’s description of his community? And in any case, how would one film it?

Simon and Burns have solved the problem by distributing the tale among the members of their gifted cast. Our perspective widens as we focus first on Philip’s confident and attractive father, Herman Levin (Morgan Spector), then on his mother, Bess (Zoe Kazan), and finally on their friends and extended family. The added room given these secondary characters allows the writers and actors to let it rip, expanding and translating Roth’s story in a new medium without traducing it.

Philip’s aunt Evelyn (Winona Ryder) remains the silly, selfish opportunist of the novel. But look for the alternating layers of disappointment, fear, giddy hope, and revulsion that twitch and ripple across Ryder’s face as she conspires with the man who might just lift her out of spinsterhood. One feels real sympathy for Evelyn in the early scenes. Her beau, Rabbi Bengelsdorf (passionately portrayed by John Turturro), spins his narcissistic eloquence so smoothly that he seems to have convinced himself that he is the savior and not the betrayer of his own people.

Similarly, Caleb Malis’s portrayal of Sandy, Philip’s older brother, convinces us that an unremarkable kid, stimulated by his desire to act on the heroic scale, not the small-potato space his parents occupy, could become the teen who shouts, “you’re nothing but ghetto Jews” at his parents. Yet it becomes the task of precisely these parents to take on the unraveling of their family, their Jewish community, and the country itself. Though neither has had experience dealing with cataclysmic events—no one does until they do—each proves capable of admirable resistance. Bess has charged moments of restrained motherly strength and calm, but the electric power of Zoe Kazan’s performance erupts in her final encounter with her traitorous sister. (I was reminded of the exquisite moment in the 1995 film of Sense and Sensibility when Emma Thompson’s Elinor begs her sister not to die and leave her alone—here the rage rolls over the love in an eerie reversal.)

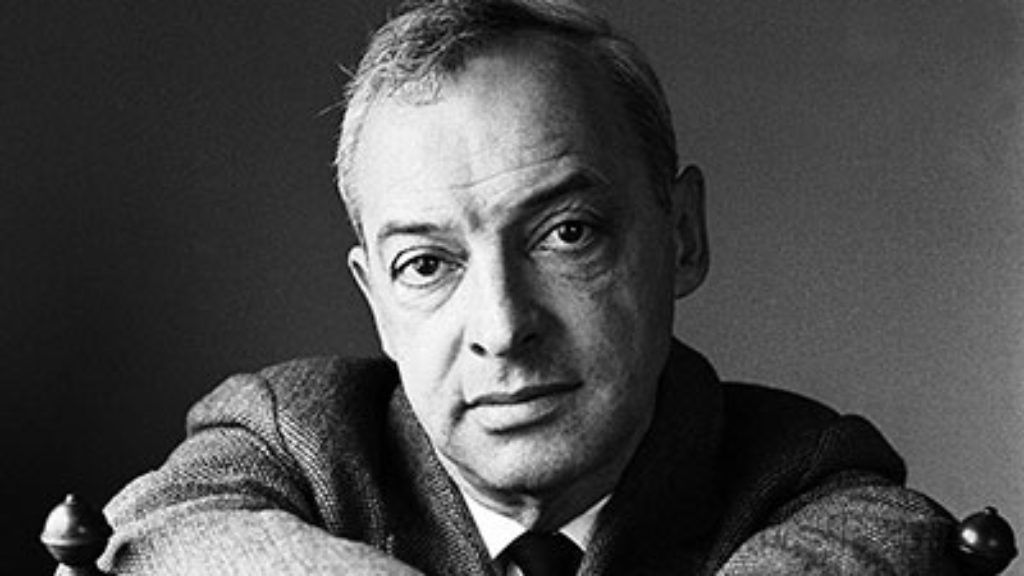

Inevitably, a creative adaptation means more than changes in perspective. The hapless orphan Alvin is no longer a goofy, tragic misfit. The dashing Alvin (Anthony Boyle, looking in profile very much like the young Saul Bellow) of Simon and Burns’s series steps forward to steal the show. There’s an unresolved challenge in the novel—where’s Lindbergh?!—and surprisingly, Alvin’s role expands to provide the answer. It’s a wacky plot twist, but Roth’s story itself has just enough of the improbable about it to admit such a clever innovation.

That selfish brutes and collaborators bubble to the surface in times of crisis doesn’t surprise us, but it was Philip Roth’s genius (and also a loving tribute to his dead parents) to show how some ordinary people can emerge as heroes. They resist, protect, oppose, and, above all, accept responsibility. As the novel’s America disintegrates, Roth writes a sentence that begins, “Where chaos reigned . . .” We would be well within our readers’ rights to expect a nihilistic conclusion like “nothing mattered,” but instead Roth concludes, “everything was at stake.”

The “perpetual fear” and “rage against what happens” of Roth’s counterfactual story come through in this version, but don’t expect the comfort of the novel’s sudden reassuring return to sanity and history as we know it. Nothing is neatly resolved. When the show ended, I briefly wondered whether I had miscounted and had one last happy-ending-episode to go. Expect to be unsettled.

Burns and Simon’s Plot Against America offers an interesting twist on our hunger for a contemporary political reading of Roth’s alternative history. In these searing episodes, the decent characters have an urgent sense of all that might be lost. A mensch like Herman Levin longs for nothing more than American normalcy—a home, a job, a loving family. As for the series’ innovation of our orphan Jersey boy Alvin as hero—capitalist Alvin in his two-tone spats and snazzy fedora—he delivers as swift a kick in the pants to our own would-be socialists as to our would-be authoritarians. That was unexpected.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Live Wire

Bellow’s not so innocent knock in The Adventures of Augie March is generally taken as the moment when Jews barged into American literature without apology.

No Joke

Roth's new novel takes surprising turns on familiar territory.

“Love Between Writers”: Saul Bellow and Bette Howland

“I thought you knew that I belonged to the Truth Party too,” Bette Howland wrote her fellow novelist, mentor, and sometime lover, Saul Bellow. Her son recently found a new cache of letters between them that illuminates two brilliant artists at work.

Bellow, Broadway Billy, and American Jewry

As Mark Cohen’s new biography reminds us, “Broadway” Billy Rose was America’s master showman for a quarter of a century. When a friend told Saul Bellow how Rose had saved a fellow Jew from an Italian prison in 1939 but refused to speak with him afterward, Bellow knew he had a story.

Rick Richman

In September 2004, the month before his novel was released, Philip Roth published a long essay in The New York Times, entitled “The Story Behind ‘The Plot Against the America’”. He wrote that the “American triumph” was that:

“despite the institutionalized anti-Semitic discrimination of the Protestant hierarchy at that time, despite the virulent Jew hatred of the German-American Bund and the Christian Front, despite the repellent Christian supremacy preached by Henry Ford and Father Coughlin and the Rev. Gerald L. K. Smith, despite the casual distaste for Jews expressed by journalists like Westbrook Pegler and Fulton Lewis, despite the blindly self-loving Aryan anti-Semitism of Lindbergh himself, it didn't happen here. … Why it didn't happen is another book, one about how lucky we Americans are. I can only repeat that in the 30's there were many of the seeds for its happening here, but it didn't."

Roth was not a fan of George W. Bush, to say the least. But at a time when the media was replete with photos portraying Bush as “BushHitler” because of the war in Iraq, Roth concluded his essay as follows:

“Some readers are going to want to take this book as a roman clef to the present moment in America. That would be a mistake. I set out to do exactly what I've done: reconstruct the years 1940-42 as they might have been if Lindbergh, instead of Roosevelt, had been elected president in the 1940 election. … [My effort was not] to illuminate the present through the past but to illuminate the past through the past."

The key to understanding Roth's novel is to appreciate the historical fact that it didn’t happen here, and that it was not simply luck. Eventually more than 400,000 Americans died in World War II to make sure it didn't happen here, and to secure our extraordinary freedoms.