A Murder in Miropol

Wendy Lower was reading through Nazi reports at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, looking for evidence against Bernhard Frank, a key figure in the murder of more than fifty thousand Jews in Ukraine and Belarus during the late summer and early fall of 1941, when a colleague asked her to look at a photograph. Lower, a distinguished historian who teaches at Claremont McKenna College, had seen thousands of Shoah-era images. Still, she was unprepared for what she saw in the photo, which she would spend a decade researching.

The photo had been brought to the museum by two journalists from the Czech Republic. They also brought documentation that said it had been taken in Miropol, Ukraine, on October 13, 1941. It shows a group of men (five are visible), a woman, and a small boy standing at the edge of a ravine, surrounded by a forest. Some of the men are wearing Nazi uniforms, but others are in civilian clothes. They hold guns pointed at the woman. Bent over at the waist, she holds the boy’s hand, her head shrouded by gun smoke. The image is reproduced on the third page of The Ravine; four detail photos, cropped from the original photo and enlarged, follow over the next few pages. “It must have been mid-morning,” Lower writes of the scene, gauging the way the sunlight throws shadows and the sharp contrasts between light and dark, between “the boy’s neatly cut dark hair and his stark white face.”

We, too, have seen Holocaust photographs, perhaps too many. But the photo at the center of The Ravine is uniquely terrible, a still image that captures Jews precisely at the moment in which Nazis murdered them. There are “not many more than a dozen” like it in existence, Lower tells us; she can describe them all in less than a single page. This photograph, our photograph, was found in the Prague headquarters of a Soviet-era “security service,” part of the flood of World War II war crimes documentation that emerged after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. With it came a few pieces of paper, records of an interrogation of the photographer, a man named Lubomir Škrovina, that reveal why and how he came under scrutiny for taking this photo, one of five he took that day in Miropol.

Lower was already known for her scholarly work on the Holocaust in Ukraine when her previous book, Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, was published in 2013 to wide acclaim. Its many readers will find the basic structure of that earlier book unchanged in The Ravine. Her narrative begins in the present day in a Shoah archive, then knits that moment with the past events she explores in the book. Lower’s research for The Ravine was prodigious (her notes stretch over sixty-two pages), but she is also a riveting storyteller, and she has carved away virtually all unnecessary linguistic adornment, leaving a succinct, precise account that is nonetheless gripping. Lower simply shows us what she saw and lets us feel the weight of it; it’s almost too much to bear. There are moments in The Ravine that hit me with such force that I could only put the book down and walk away—sometimes for days. Publishing catalogs are awash with titles about the events of the Nazi era, but I cannot think of another in recent years as powerful.

Of the photograph, Lower writes:

My eyes were always drawn back to the center, to the crouching woman, and I began to wonder why she was bent over in a perpendicular angle, not buckling under or kneeling forward. And then I saw something resting on the woman’s lap or being held in her right arm. It was a hazy, curved form; light was not passing through what should have been an empty space. I could make out a pair of bent knees and the translucent fabric of a dress. I started to see the faint lines of an elbow and a small head covered in a scarf. Suddenly into my view came the existence of another person, a child.

It is shocking how close that murdered child came to being erased entirely, with no record of her existence. Processing the prints taken that day in Miropol was a delicate operation in the early 1940s. Without a precise combination of temperature, agitation, and time, the child would have been invisible. Looking more closely at the photograph, I thought of the famous talmudic saying that the person who saves a single life is considered as if they saved an entire world. Is there a reward for saving the memory of a single life? And if so, to whom does it go?

It’s doubtful that Lubomir Škrovina ever heard of his contemporary Orson Welles, but he would have probably understood the director’s assertion that “the camera is much more than a recording apparatus; it is a medium via which messages reach us from another world.” Indeed, Škrovina’s attempts to bring a message from the world of the “Holocaust by bullets” landed him in an interrogation room in the headquarters of Slovakia’s secret service in Bratislava.

“I assumed that the photographer of the atrocity in Miripol was a collaborator, standing at close range in military uniform, helping to prevent the Jewish families from fleeing, and humiliating them by taking their photos at such a moment,” Lower writes. As the historical records show, who and what he was accused of being and doing shifted with the quickly changing political ground of Europe in the middle of the twentieth century.

Drafted into the Slovakian army, Lubomir Škrovina was sent with his unit to Ukraine in 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. He served as a “guard and a company scribe” on the Germans’ eastern front. He was later denounced to the authorities of the Nazi-allied government for “making photos that were not permitted,” photos that “worked against the New Order in Europe.” At the interrogation, he was accused of protecting Jews and working for the Slovakian resistance. He admitted to photographing a massacre of Jews in Ukraine but claimed that “these pictures were taken publicly with the approval of German commanders” and that he had subsequently burned them so that they didn’t “end up in the wrong hands.” His first assertion is verified by the photos he took that day; they clearly aren’t taken from a hiding place or with a concealed camera. As Lower tells us:

The photographer stands about twenty feet from the executioners (his camera did not have zoom or telephoto lenses), while the helper (possibly an interpreter, gravedigger, or confiscator) walks or stands near him without any expression of alarm. . . . It seems that the photographer is permitted to be there, perhaps as part of the cordon of guards, and is openly snapping pictures. . . . The photographer knows what he’s doing—the image is clear and composed. It even follows photography’s basic “rule of thirds” in the positioning of the main panels: the ravine, the dying victims, and the killers.

While Škrovina had burned the photographs as he said, he had also retained the negatives so he could make new prints as proof of the horrors he had witnessed. In 1958, he was questioned again by the KGB and Czechoslovakia’s state security forces rooting out those who had collaborated with the Nazis. The information that almost doomed him during World War II, including the risks he in fact did take to help Jews escape from the Nazis and aid the Slovak National Resistance, saved him after the war.

The pictures shown in the book are only a few of those Škrovina took in his months on the eastern front. In packages to his Czech wife, Bohu, he sent film, along with instructions for getting it developed safely and distributed to those who might use the photos. “Think hard about what to release, then adopt the radical solution and stick to it,” he wrote.

When he returned home on leave in December 1941, he was able to fake an illness that let him avoid being sent back to the front. He joined the Resistance, hiding Jews in his home and leading some of them to the partisans in the forest:

One of them was Škrovina’s neighbor, Dr. Latislav Gotthilf, an obstetrician/gynecologist with a wife and a five-year-old son. When Bohu became pregnant, Dr. Gotthilf cared for her and in October 1942 delivered Lubomir Škrovina Jr. into the crossfires of Nazism and Stalinism. Sometime in 1943 or the first half of 1944, Gotthilf joined the medical corps of the Slovak resistance movement encamped in the mountains and forests around Škrovina’s home, and brought his wife and son with him.

The chapter titled “The Photographer” reveals how painstaking Lower’s research efforts were, as she pushes against bureaucracy time and again to see not just digitized versions of Škrovina’s images but the originals in the “cold storage” intended to preserve them. By the end of the book, the reader will travel with her to meet Škrovina’s children in present-day Slovakia, where she is given permission to search the photographer’s attic and personal effects. She finds a pipe he can be seen with, if you look closely, in a photo from Miropol taken a month before the massacre he documented.

From a crime report filed in Germany in 1969, Lower learned the names of the German killers, who were customs guards. From the files of a Soviet prosecutor in 1985, she was able to identify the Ukrainian militiamen. And from deep research across multiple archives over many years, Lower may have uncovered the identity of the victims, though she can’t be certain. (At least one detail in the photo argues against her identification.) As she notes, records from the Jews of Eastern Europe are not as plentiful as those from countries such as the Netherlands and France; half of the Holocaust’s unidentified victims were murdered in Ukraine.

Lower’s account, however, does more than just reveal the facts about the Jews in the photo and their executioners. The specifics of these murders in this Ukrainian town epitomize the years of the Nazi terror more generally. The book could well serve as a compelling introductory text for those who have had little to no introduction to the Holocaust. One can imagine a skillful instructor using a chapter, and in many places just a few pages, as the foundation for a college class.

Susan Sontag famously asserted that the shock of atrocity photography “wears off with repeated viewings.” Lower disagrees, writing that “the risk of desensitization to such images exists when we have no knowledge of their history and content”—a history that she has painstakingly worked to provide. I am inclined to side with Lower. While reading her deeply researched, morally scrupulous retrieval of one particularly terrible moment in history, I thought often of a line Agnon puts in the mouth of the shamash of the Buczacz synagogue. “Suffering is hard,” he says, “hard when it happens and hard afterward.”

Suggested Reading

Law, Justice, and Memory in Poland

Under the Law and Justice Party, Poland has just criminalized the life stories of its Jewish survivors. Here’s why.

Killer Backdrop

If Auschwitz can have a gift shop, why can’t the Warsaw Ghetto have a love story?

Not of This World

In writing his first book for young readers, Aharon Appelfeld seems to have split himself and his life story between the two title characters: resourceful Adam, a boy of the land whose knowledge of the forest keeps them safe and fed, and bookish Thomas, a doubter in both faith and his own abilities.

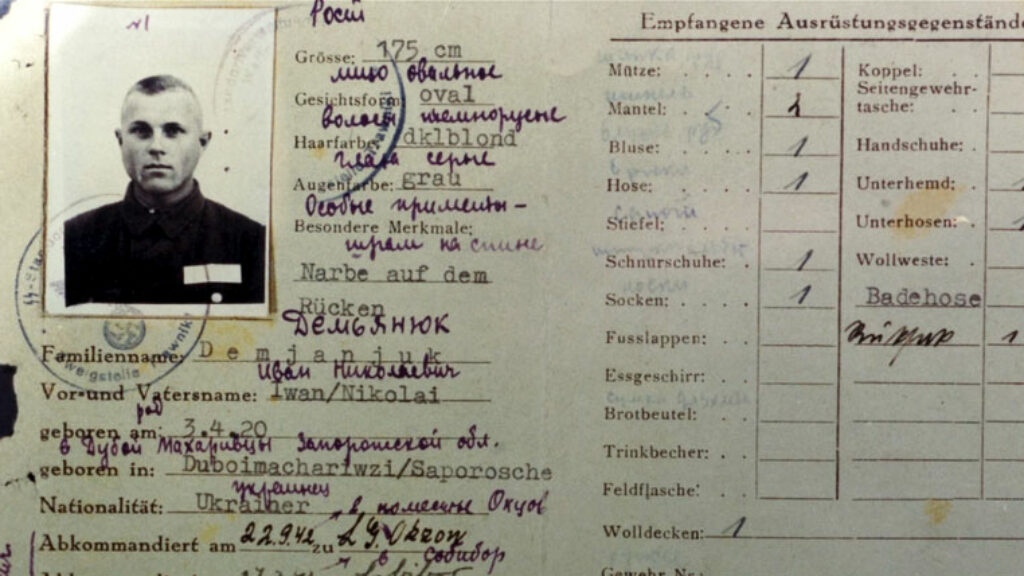

Ivan the Terrible?

A new miniseries from Netflix manages to maintain the tension of the long-decided, if not entirely resolved, case of John Demjanjuk.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In