Ivan the Terrible?

When Ivan “John” Demjanjuk went on trial in Jerusalem in 1987, it seemed all but certain that he would be sentenced to death for his role as a Treblinka gas chamber guard who helped send three-quarters of a million Jews to death. That guard—perhaps Demfjanjuk, perhaps another Ivan with the surname Marchenko—had earned the moniker Ivan the Terrible because he “delighted in using a blade—I think a sword even—to torture people in their final moments,” according to Eli Rosenbaum, head of the Office of Special Investigations (OSI), the US Department of Justice’s so-called “Nazi-hunting unit.” In a new polyphonic documentary on Netflix about Demjanjuk, The Devil Next Door, Rosenberg is among those who are convinced that Demjanjuk was the Ivan the Terrible. But not everyone, Demjanjuk’s family, in particular, is as confident in the veracity of the accusation.

The case against Demjanjuk, who faced public scrutiny from the 1970s until his death in 2012, sits at the center of the five-part documentary miniseries that raises compelling and vexing questions about international law, about the trial’s methods and motivations, and about the nature of guilt and innocence. The documentary’s central questions about Demjanjuk’s identity set the series in motion: Was Demjanjuk Ivan the Terrible, “a terrible Ivan,” or, as he and his family insisted, an innocent family man wrongly accused of heinous crimes?

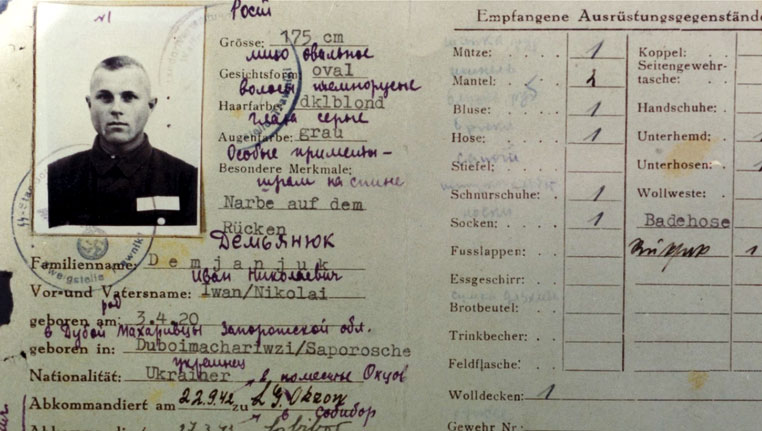

In the late 1970s, an ID card from World War II—a so-called Trawniki card, given to Red Army soldiers who were captured by the Germans and recruited as Nazis, often to avoid suffering as POWs—was given to the Americans by the Soviets. Its appearance would upend the quiet life Demjanjuk had made after immigrating to America in 1952, working as a mechanic for Ford and raising a family in the Cleveland suburb of Seven Hills.

Officials at OSI and Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) were convinced the card identified Demjanjuk as a Nazi collaborator who had lied on his US visa application. After more than a decade of legal battles, he was scheduled for deportation from the United States, but to where? He had no home country to which he could safely return. He faced execution if he returned to Ukraine, and Germany had no claim on him because his alleged crimes happened in Poland. In the end, Israel agreed to extradite him because of the Trawniki card and eyewitness testimony that placed him at Treblinka. There, in a televised trial, he would face charges under the 1950 Nazis and Nazi Collaborators Punishment Law. As with Adolf Eichmann some 25 years earlier, the prevailing assumption was that justice would again be served: death by hanging.

Instead, the case dragged on. Serious doubts emerged about the authenticity of the Trawniki card. Remarkably, the vigorous Israeli defense team publicly called into question—the trial was simulcast on TV and radio—the motives of the prosecution in using Treblinka survivors’ eyewitness testimony. What good is such testimony 40 years after the crime? Defense lawyer Yoram Sheftel argued that “in the atmosphere of the court, with the cameras on” such testimony was closer to theater than reliable evidence.

Although the details of the trial have been told at length in superb reporting by Lawrence Douglas in his book The Right Wrong Man, this documentary’s success is rooted in its deep engagement with the endlessly compelling visual record of the proceedings (which had to be unearthed and digitized). This archival footage is supplemented with a similarly compelling series of interviews completed some 30 years later. Together, the trial footage and retrospective interviews propel the story through murky, unanswerable questions.

By recreating the flow of a trial—shifting back and forth between the “two sides” (the defense, including Sheftel and Demjanjuk’s family, and the prosecution, including Israeli lawyers and the OSI as well as the Israeli judges, who initially sentenced him to death)—the miniseries maintains tension in the long-decided, if not entirely resolved, case. Among the doubts that linger is whether Demjanjuk might have been a guard at Sobibor rather than Treblinka: a terrible, culpable Ivan, but not the Ivan. (A subreddit full of theories about Demjanjuk’s identity has sprung up around the show.)

Yoram Sheftel, Demjanjuk’s infamous defense lawyer, looms large in this retelling. Theatrical and often antagonistic, Sheftel describes himself as “a person who refuses to obey the general norms”—a fair self-description, given his willingness to question the validity of Holocaust survivor testimony. His suspicion that the trial was a “farce, cover-up, a frame-up, and a show trial” led him to defend Demjanjuk even though the Israeli public had presumed unequivocal guilt.

As the face of Demjanjuk’s defense, Sheftel became something close to an Israeli public enemy. He claims to have been banned from his synagogue. In 1988, a survivor attempted to seek revenge for his parents, murdered in the Holocaust, by hurling acid at Sheftel’s face during a funeral (for another Demjanjuk attorney who died by suicide). The attack left him nearly blind in one eye. His presence in the documentary, including the archival footage of him with the judges and the press, gives the miniseries a dynamic charge.

Throughout the interviews completed for this documentary, Sheftel thrives in his role as a contrarian. His words elevate the potential conspiracy against Demjanjuk to something worthy of consideration—something you don’t want to believe but find yourself going back to the record to better understand. I found myself recalling my ingrained commitment to the right to a fair trial as I watched Sheftel “antagonize.”

We see Demjanjuk, waiting for his first hearing in Israel to begin just hours after his arrival. Knowing that cameras are trained on him, he looks at the investigators and says, almost jubilantly, “Shalom!” What is the message behind his grin? We see him again (and again) pacing in his cell in archival surveillance footage. Throughout his seven-year trial and appeal process, Demjanjuk was kept in monitored solitary confinement (for his own protection was the claim) in Ayalon Prison, where Eichmann was hanged.

Ed Nishnic, Demjanjuk’s son-in-law, tells how the executioner’s gallows were constructed in a room next to Demjanjuk’s cell; there was no escape from hearing each strike of the hammer.

The documentary relies on numerous interviews with the Demjanjuk family to provide the counternarrative to the prosecution. Even when they are not speaking, their sullen faces and prolonged hugs with a man just sentenced to death represent the pain of people who have been separated from their husband, father, and grandfather.

The miniseries’s editing places the family’s dissolution and pain in the close company of emotional courtroom testimony from several Treblinka survivors. The Demjanjuk family attended the trial, sitting in a gallery filled with survivors hoping, perhaps praying, for a conviction. Through this juxtaposition, the show refuses to allow the viewer to forget that this was a trial, with two sides—perhaps a fact that, given the title and the horrific allegations against Demjanjuk, are not always at the fore.

What might be the documentary’s most memorable scene occupies parts of two episodes, involving the star witness, Eliahu Rosenberg. While a prisoner at Treblinka, Rosenberg had the job of removing bodies from the gas chambers. He also testified in the Eichmann trial decades prior. During his testimony, Rosenberg asked the judges to ask Demjanjuk (refusing to address him directly, it seems) to remove his glasses and bare his eyes. Doing so, Rosenberg claimed, would solidify the identification. Demjanjuk agreed, and whispered one condition to his lawyer: “I want it that he come in close to me . . . right here,” pointing to the floor in front of the stand.

With the terms set, Rosenberg slowly made his way across the stage, “in front of the tribunal.” Within a few seconds, the two men were standing face to face. The moment becomes excruciating when Demjanjuk extended his hand to Rosenberg. “How dare you,” Rosenberg said, withdrawing in a sharp motion “as if he’d seen a snake,” Judge Dorner later recalls. The camera swerves to the gallery, where Rosenberg’s wife had fainted. “That is the devil,” Rosenberg said, returning to the stand. He has no doubt that Demjanjuk’s “murderous eyes” are those of Ivan the Terrible.

It would be tempting to treat this testimony as fact. The Israeli prosecution and judges did just that: “Why shouldn’t we trust our own people?” they asked. Why would we doubt the validity of the most traumatic memories imaginable? But Sheftel, to put it mildly, took his role as defense attorney seriously, claiming that Rosenberg’s accusation “was a sheer lie.”

The defense introduced a signed, 64-page testimony from 1947, in which Rosenberg claims that “we” killed Ivan in a 1943 uprising. When Rosenberg was questioned about this extraordinary discrepancy, he replied, “It was my heart’s wish. Of course I believed that he was killed.” Demjanjuk, furious, leaned into his microphone, screaming “liar! liar! liar! ” at Rosenberg. Here the documentary allows the scene to unfold and for the evidence to sit with us.

Questions remain about how and why the Israeli Supreme Court acquitted Demjanjuk in 1993, as well as qualms over potential deceptions of the Office of Special Investigations. The series turns those qualms into full-fledged allegations of misconduct against the OSI for its decision to withhold its doubts about Demjanjuk’s identity from the Israeli prosecutors.

Conspiracy theories swirl about whether the Soviets manufactured evidence, seeking to drive a wedge between two anticommunist groups in the United States, the Ukrainians and Jews—intriguing but conspiratorial. In 2009, a German court used new evidence to place Demjanjuk at Sobibor, not Treblinka; he was convicted for being an accessory to 27,900 murders. But The Devil Next Door addresses this conviction more as an afterthought than a serious conclusion to the saga.

In a reach for some sort of narrative closure, the documentary’s final moments show Demjanjuk’s grandson using a refrain common in defense of wartime behaviors and actions: His grandfather might have played some role in the Holocaust, but only to survive. Like the final charges against Demjanjuk, which were ultimately vacated because he died during the appeal process, there is no clear answer. It isn’t clear, and perhaps never will be, if Demjanjuk was “Ivan the Terrible” or another terrible Ivan.

Suggested Reading

Law, Justice, and Memory in Poland

Under the Law and Justice Party, Poland has just criminalized the life stories of its Jewish survivors. Here’s why.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Stepan Bandera: A Rejoinder to Dovid Katz

Konstanty Gebert responds to Dovid Katz's critique.

Dust-to-Dust Song

Nelly Sachs was 50 years old when she fled the Nazis with her mother in 1940. Few would have perdicted that she would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature twenty-six years later.

When Everything Matters

Bellow on Roth on TV.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In