Where She Has Gone

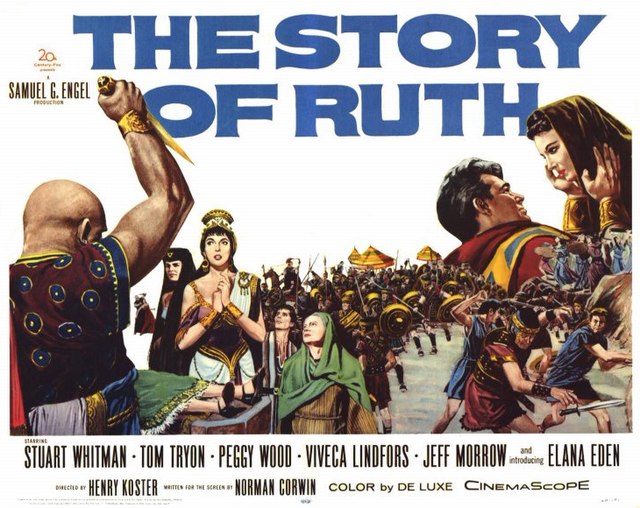

Guillermo del Toro’s Academy Award–winning film The Shape of Water tells the fantastical tale of a mute cleaning woman named Elisa who falls in love with a humanoid amphibian creature with magical powers. The couple eventually escape the clutches of evil scientists and swim away together. Elisa lives in a dingy apartment above the Orpheum movie theater, whose marquee displays the title of a real 1960 film, The Story of Ruth. Scenes from that earlier film appear throughout The Shape of Water, with the Amphibian Man shown enjoying the portrayal of the titular heroine by the Israeli-born star Elana Eden. As the New York Times noted in its coverage of del Toro’s film, “the most famous verse” in the book of Ruth “has the woman imploring her mother-in-law not to sever their familial tie, insisting, ‘Where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge’—a sentiment that reverberates throughout this gentle, yet seemingly impossible, love story.”

Inspiration for Oscar winners is hardly the most surprising resonance Ruth has had, as Ilana Pardes shows in her biography of the biblical story, Ruth: A Migrant’s Tale.

Ruth’s four chapters tell the tale of Naomi and her husband, Elimelech, who flee Israel during a famine. After the death of her husband and their sons, a bereft Naomi journeys back to Bethlehem with Ruth. Through the kindness of the wealthy landowner Boaz, who marries Ruth, the women are economically and spiritually redeemed. Though the tale would seem to be a straightforward tale of courage and kindness, it has sparked a range of responses in its readers, many of which Pardes surveys. There are the kabbalistic mystics who saw in the figure of Ruth a means of understanding the feminine aspects of God, the seventeenth-century French baroque artists who used the book’s agricultural setting for pastoral landscapes, twentieth-century kibbutzniks who sensed a formidable forebear, and a beat poet who searched for solace in its verses.

Pardes’s slim, elegant volume, part of the Yale Jewish Lives series, prefaces the reception history of the book by succinctly and engagingly offering a literary analysis of the biblical text. Drawing on earlier scholarship, she offers an accessible but nuanced analysis, in which she successfully works to remain “attuned to the dramatic qualities of Ruth’s tale—to the exquisite dialogues” and “network of interconnections between Ruth’s tale and the tales of other biblical characters,” while also telling the story of its later reverberations.

Take, for instance, Boaz and Ruth’s pivotal nighttime encounter at the threshing floor in chapter three. Noting the “uncanny resemblance” of this story to the seduction of Lot by his daughters in Genesis 19 after Sodom’s destruction, Pardes writes that “the spirit of Sodom lurks behind the threshing floor of the book of Ruth.” Judah and Tamar’s illicit encounter in Genesis 38 is also echoed in the encounter. Ruth, of course, is a descendant of Moab, the product of Lot’s relations with one of his daughters. Boaz, in turn, descends from Peretz, one of the children Judah produced with Tamar. And, of course, as we are told in the genealogy that concludes the book, King David was the great-grandson of Boaz. Thus, Ruth’s marriage to Boaz is, Pardes writes, “an acknowledgement that the house of Israel was from the very outset ‘built’ through semi-transgressive acts that turn out to be far more beneficial than one would expect.”

In discussing the symbolic names in the book, Pardes quotes the suggestion that the name Ruth likely means “friend.” In contrast, Orpah, the name of Naomi’s other daughter-in-law who returned home to Moab instead of heading to Bethlehem, likely comes from “nape,” prefiguring her decision to turn away from Naomi. Naomi’s own name, “pleasant,” is consciously punned upon by the character herself, who laments to the women of her hometown that they should no longer call her by that name because God has embittered her.

Curiously, Pardes neglects to note that Naomi’s sons, Mahlon and Kilyon, possess names that translate to, roughly, “afflicted” and “goner,” reflective of their fate in the book’s opening chapter. The literary significance of Boaz and Ploni Almoni’s names also goes unmentioned. The former’s can be translated as “in him is strength.” Ploni Almoni, that is “so and so,” or John Doe, is the man who had the first opportunity to marry Ruth and declined, failing to “maintain the name of the dead.”

Pardes also notes the parallel between Boaz’s praise of Ruth’s having left her birthplace to journey to Israel and the patriarch Abraham’s own departure from the land of his father. Perhaps because her book is aimed at a broad English-speaking audience, Pardes does not mention the textual anchor that supports this juxtaposition. Ruth’s pledge to Naomi, “wherever you go, I will go” (ki el asher telkhi ’elekh), is the only other doubling of the word “go” in the Bible besides God’s commandment of Abraham, lech lecha.

It is in tracing Ruth’s artistic afterlives that Pardes breaks new ground. She argues that, in their special focus on Ruth, medieval Spanish kabbalists were reacting to the rise in popularity for the Christian cult of Mary. Seeing the roadside shrines, dramatic plays, and street processions, they decided to “upgrade” Ruth—their own foremother of the future messiah, son of David. “They wanted,” she writes, “a messianic heavenly mother who would have compassion for an entire community, mourn their dire condition in exile, and intervene on their behalf in the upper world.” Mining the Zohar and related Midrash Ha-Ne’elam, Pardes shows how Ruth then became identified with the feminine Shekhina, the worldly manifestation of the otherwise hidden God.

According to this kabbalistic tradition, Ruth’s birth name was actually Gilit (from the Hebrew for “revealed”), and she became Ruth only after converting to Judaism, the migrant female who symbolized the divine presence that followed Israel into exile. The Midrash Ha-Ne’elam glosses Boaz and Ruth’s encounter at the darkened threshing floor as follows:

I am Ruth your handmaid—brimming with sorrow, overflowing with pain over my children in exile, and over the holy palaces, for I have been exiled from My sanctuary. And it is not enough that I have been banished, but they abuse and curse Me every day on account of them, and I have no voice in exile to respond.

Boaz’s response to “stay for the night” (3:13) is seen, from this perspective, as an allusion to the deferment of the messianic arrival. Thus, God says to his Shekhina:

Stay for the night—stay now in exile and guide Your children there with Torah and good deeds. If their good deeds aid your redemption, You will be redeemed. If not, [then in the morning . . .] I will redeem you myself . . . for morning and the light of redemption will come.

The later Zoharic text, Tikkunei Zohar, adds another dimension to Ruth’s link to the divine. Noting that Ruth has the same letters in Hebrew as tor (turtledove)—whose voice, Song of Songs tells us, “is heard in our land”—Rut/Tor becomes identified with the Torah itself (the same letters, plus a hey), given voice by those who study it. This is an early source for the kabbalistic practice of Tikkun Leil Shavuot, staying up all night learning. Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his rabbinic colleagues are said to have stayed up all night getting ready for the festivities of the coming daytime reunification of the male and female aspects of God. In the eyes of the rabbis who later popularized the practice, the giving of the Torah on Shavuot was “inseparable from the wedding ceremony of the Shekhinah and her divine consort.” In preparation for this divine union, the bride was adorned with “the most refined adornments,” scriptural texts whose recitation gives voice to “the song of Torah”—that is, of Ruth.

Needless to say, Ruth has also inspired less symbolically and ritually elaborate but no less interesting works. Nicolas Poussin’s Summer: Ruth and Boaz was commissioned by the great-nephew of Cardinal Richelieu and today hangs in the Louvre. It is part of a series in which Adam and Eve in Eden represent spring, autumn depicts the Israelite spies returning from their mission with a cluster of grapes, and winter is Noah’s flood, but Poussin was the first to depict Ruth as representative of the joy of summer. Amid the sun’s bright rays, the soft, warm colors of the sheaves shine, matching the hues of the harvesters’ attire. This, Pardes writes, is the painter’s attempt to capture “nature and humanity at their best,” a romantic idyll.

Two hundred years later, Jean-François Millet’s Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz) portrayed an altogether bleaker scene. After all, those who glean, as Ruth did before her marriage to Boaz, are the poor and malnourished, exhausted from laboring under the hot sun. Pardes notes that the Bible’s lack of physical description of Ruth gave artists the freedom to imagine her in line with their cultural and even political purposes. “Perhaps,” she writes, “the lack of specific information gave them the freedom to imagine her in whatever way they deemed appropriate.” For some, Ruth represents optimism, an outsider whose kindness redeemed her new nation. For others, her struggle amid the alien corn is that of all who toil in a post-Edenic world by the sweat of their brow.

To the early sweat-drenched kibbutzniks, Ruth was the paradigmatic olah. The 1918 photo Woman in Biblical Scene, by the Bezalel school’s Ya’acov Ben-Dov, shows a student dressed like Ruth gleaning in a field, with the blurred school building visible in the background. By contrast, in his 1923 novella, In the Prime of Her Life, S. Y. Agnon offered a retelling of Ruth’s story that questioned whether the modern Zionists’ biblically focused return was really possible. Agnon invited his reader to consider why, in a homecoming, a deep sense of estrangement often still remains.

To Allen Ginsberg, Ruth was his mother, even though her name was Naomi. In “Kaddish (For Naomi Ginsberg, 1894–1956),” she becomes “Ruth who wept in America”:

Down the Avenue to the south, to—as I walk toward the

Lower East Side—where you walked 50 years ago, little

girl—from Russia, eating the poisonous tomatoes

of America—frightened on the dock—then struggling in the crowds of Orchard Street toward what?

Ginsberg’s Ruth is an immigrant unable to glean enough in the fields of America (those tomatoes, frighteningly unfamiliar to a Jewish girl from Russia, the forbiddingly crowded street called “Orchard”) to survive, too lost to find a true Boaz, let alone salvation.

Though Pardes does not include it, a more positive invocation of Ruth’s journey into the unknown occurred amid the harshness of World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s closest adviser, Harry Hopkins, attended a dinner in Britain in January 1941 with Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Though the US would not enter the war for almost a year, Hopkins was there to show the US’s support for the Allied cause. At the dinner, Hopkins turned to Churchill and said:

I suppose you wish to know what I am going to say to President Roosevelt on my return. Well, I’m going to quote you one verse from that Book of Books. . . . ‘Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.” Even to the end.

Unlike other biblical stories whose reception has tended to be thematically consistent—the Exodus as a call to revolution, Queen Esther as a source of political courage—Ruth’s has migrated across a range of meanings. The Moabite immigrant widow, Israel’s unlikeliest of heroines, has walked alongside those who felt lost. She has modeled strength, suffering, and even the divine presence, while inspiring empathy for the marginal and support for those who stay up all night on Shavuot, all sharing the hope that wherever she goes, they, too, will go.

Suggested Reading

“Wherever You Go, I Will Go”: Reading Ruth 1:16-17

It is traditional to read the book of Ruth on Shavuot. Leon Kass has been reading it with his granddaughter, and the result is a new book.

Love and War

David Grossman has for sometime been one of Israel's most talented and important writers. In many of his novels, his feeling for adolescence—one is tempted to say, his identification with it—has been so brilliantly intuitive that the imagining of adulthood has scarcely been possible. In To the End of the Land, Grossman makes his breakthrough.

Inside or Outside?

After the discoveries of the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars of Judaism slowly began to reconstruct the 400-year period separating the latest parts of the Hebrew Bible from the earliest rabbinic compilations.

Talmuds and Dragons

Like the medieval literature to which it pays homage, The Inquisitor’s Tale weaves in supernatural events and divine interventions, mythic beasts and wild peoples, and even entrées into medieval theology, all liberally peppered with puns and potty humor.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In