Enlightenment and Conspiracy

In December 2023, I found myself in the basement of a Yale dorm, watching a new documentary about young American Jews. Israelism follows Simone Zimmerman and a young man identified only as “Eitan” as they narrate their journey from being passionate advocates for Israel and, in Eitan’s case, an IDF soldier, to outspoken critics of the country. The film had already won awards at the Arizona, Brooklyn, and San Francisco film festivals and was just starting to make its way to college campuses.

I had been invited to discuss the film at Yale Hillel after it had been screened elsewhere, since the organization had decided not to allow it to be shown in its building. It was a little more than two months after October 7, and tensions were high on campus. Most students were reading for finals, but the event was still packed. After the movie, dozens of the attendees walked over to Hillel and stayed to talk long after the pizza had gone cold.

According to Israelism, the American Jewish community is committed to lying about the political plight and suffering of the Palestinians because if they told the truth, young Jews would reject Israel (and perhaps even their Judaism) in even larger numbers than they already do. The title reflects the film’s thesis, that American Jewish education has replaced Judaism with support for Israel as an intentionally dishonest anchor for Jewish identity. The film tells the story of Simone and Eitan (and, as the filmmakers have made clear, themselves) by deploying a rhetoric now widely embraced by the Jewish anti-Zionist left: “Even though Israel was a central part of everything we did in school . . . it was presented to us that Israel was an empty wasteland when the Jews arrived,” Eitan says. Later Simone says of her college self, “I’ve been through all the trainings, all the programs, and I don’t know what the occupation is, what the settlements are.” Set aside the implausibility of such statements by highly educated millennials and note the passive voice: young activists were the victims of an establishment conspiracy from which they have now awoken.

The problem at the heart of the film is real, important, and relatable. Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians has no end in sight, and the brutality of occupation—and now the war in Gaza—is uncomfortably at odds with the liberal beliefs and values of most young American Jews. Yet Israel remains central to our institutions, our philanthropy, and our communal life. The serious questions that arise from this conflict, however, are not really taken seriously in Israelism. Instead, it offers us a cartoonish polemic.

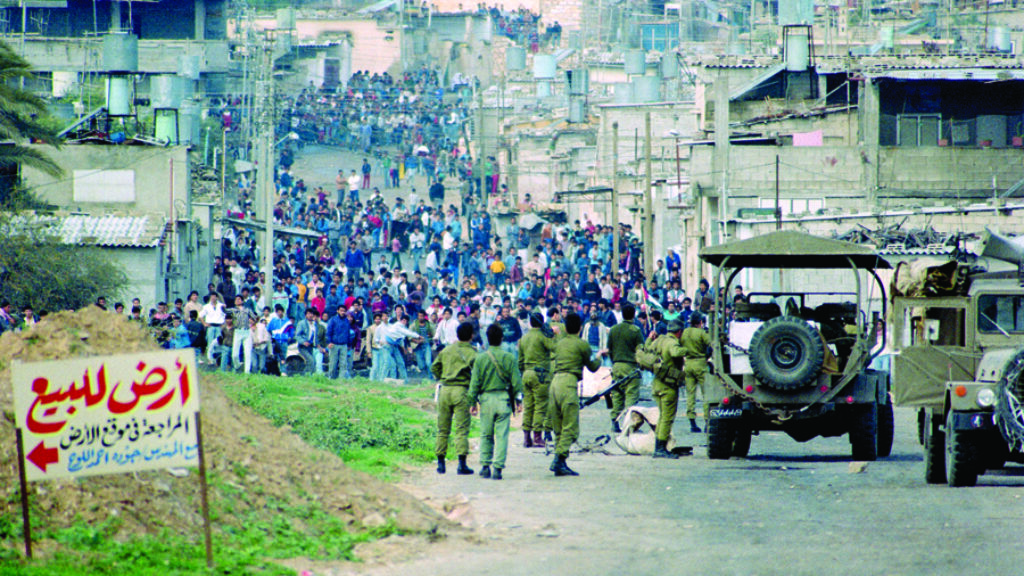

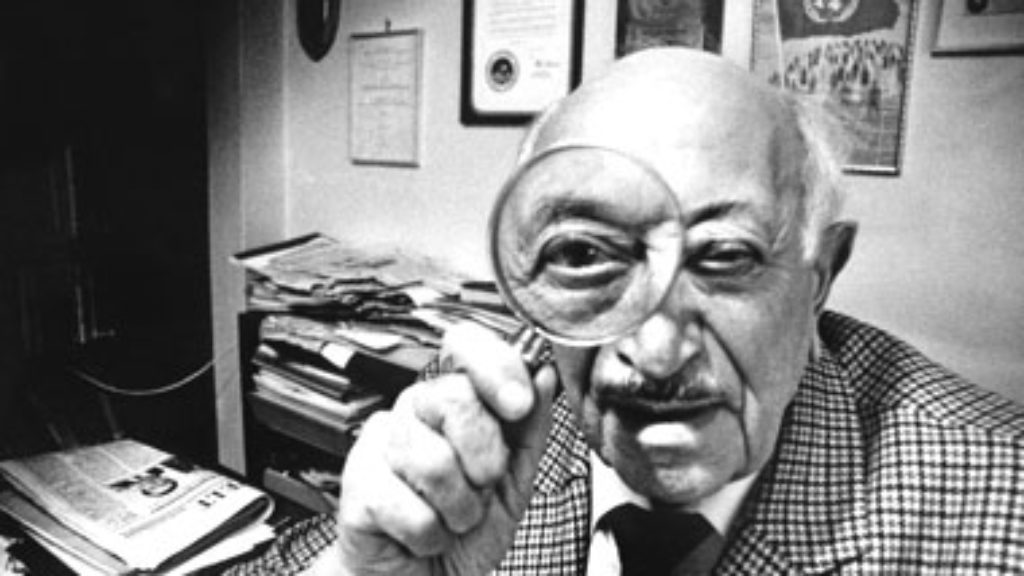

The film opens in the bombastic stadium-rock atmosphere of a Taglit-Birthright Mega Event in Jerusalem. Attractive young male and female IDF soldiers sing on stage as pictures of tanks and helicopters flash by on a giant screen and the audience cheers, dances, and waves Israeli flags. The first narrative voice is of an unidentified older man (who turns out to be Abraham Foxman, the longtime leader of the Anti-Defamation League): “The non-Jewish community does not understand our fixation, our obsession, with Israel.” Seconds later, we hear a young woman: “Everybody knows somebody who was in the army. Israeli soldiers, they’re hot, they’re awesome, they’re strong. They’re everything we could all want to be.” Then the credits roll over giddy day school kids waving flags as they parade down Fifth Avenue on Israel Day, before segueing to a West Bank shuk where a soft-spoken Palestinian man named Baha Hilo is shopping and talking. His is the first calm presence and conversational voice in the film: “I met so many nice people. Jewish Americans will tell me things like, ‘We like you, but we don’t like Palestinians,’ even though I’m the only Palestinian they know.” Within a minute, we are shown grainy footage of Israeli soldiers brutalizing Palestinians and protesters, and we hear Simone begin the story of her political awakening: “As a curious young person, like what is this thing that is so horrifying that you can’t bear to let me see it?”

Israelism proceeds to make its argument by telling the story of two American Jewish journeys: Simone’s as a tourist and Eitan’s as a soldier. What they see unmakes both of them and forces them to take a more difficult, even spiritual, journey: from malicious ignorance (the pro-Israel position in the diaspora) to benevolent enlightenment (the Palestinian position, as narrated by Palestinians).

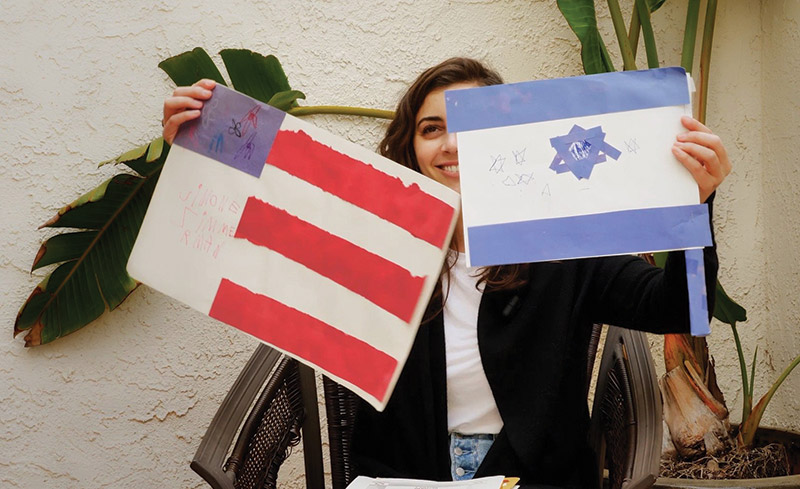

Of her upbringing in the Conservative Jewish movement, Simone says, “Israel was treated as a core part of being a Jew. . . . So you did prayers and you did Israel.” Sitting out on the patio of her family’s San Fernando Valley house, Zimmerman lays out the evidence for her indictment in the form of elementary school mementos: colorful Hebrew primers, handmade Israeli and American flags, a certificate for winning the Israeli Jubilee contest when she was seven, and so on. If not for Simone’s ironic tone, this might be taken as the beginning of a thick description of American Jewish love for and identification with Israel. But the film sees something much more sinister going on: post-Holocaust trauma and obsession with Jewish survival bred an uncritical veneration for Israel and its army. Thus, the system of day schools, youth groups, camps (which sometimes included military dress-up and war games), Birthright, and AIPAC provided two basic models for a young adult to serve the Jewish people. “You could,” Zimmerman says, “join the army or become an Israel advocate” on campus.

Eitan, who was brought up in a Conservative Jewish family in Atlanta, became a soldier: “When I was in high school, I told my parents I don’t even need to apply to college because I am just gonna join the Israeli military.” He is trained for combat and soon ends up on the West Bank, where he must obey inexplicable orders and languish complicitly in the banal violence of occupation (which the film re-creates in stark cartoons as he tells his story). He is left feeling guilty, depressed, and responsible. I had nothing but sympathy for his story.

But Zimmerman is the film’s star, especially because, in her own words, she is “like the best the Jewish community has to offer.” Nevertheless, she found herself bereft of answers on behalf of Israel when she went to Berkeley. The last image we see of Zimmerman on campus is archival footage of her crying during a public student hearing as she attempts to fight a BDS resolution. We are clearly meant to understand these as tears of confusion rather than commitment. Her journey is about to begin.

As many of the Yale students I spoke with pointed out, Israelism is so one-sided and so certain of its own virtue and rightness that critique seems almost beside the point. Palestinian activists (Sami Awad, in particular) come across as deeply humane, and their characterizations of Israelis and the conflict are never challenged. An immigrant Jew, for instance, is described by Awad as a foreigner who “just moved here to join the army and play cowboys and Indians.” And the only Jewish settler who appears in the film is callous and unlikeable.

So certain are the filmmakers that the entire history of the conflict can be summed up as one in which the Israelis are simply and only the oppressors that we are informed, “In 1967, the State of Israel managed to complete its control of Palestine by taking over the territory of the West Bank and Gaza.” No mention is made of Egypt, Syria, or Jordan, or the circumstances of the Six-Day War. Similarly, the Second Intifada goes unnamed in the film except as “a battle for Jerusalem.”

In short, what is important to note about Israelism is not its historical distortions or polemical tricks but the myth it constructs of Eitan’s and Simone’s—but especially Simone’s—journey to enlightenment. What did Simone see that the American Jewish establishment—personified in the film as an elderly Foxman rambling on in his elegant glass office high above Manhattan—didn’t want her to see, and how did it change her?

Whether the film is conscious of it or not, the archetype here is Paul, who had been the Pharisee Saul until he had a vision on the road to Damascus, not too far from the one Simone had on the streets of Bethlehem. Paul’s vision transformed him from a self-described persecutor of Christians to Christianity’s first great evangelist. He went from being fierce, ignorant, and sad to happy, articulate, and liberated, as, the film shows us, has Zimmerman. Like Paul, Simone’s conversion moved her from a self-interested cloud of particularism to a vision of spiritual universalism—“There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female,” Paul tells the Galatians.

The appeal of Paul is understandable, especially for those of us who grew up in America. The Pauline tradition brings some of the best of Jewish universalism and offers a shortcut to the theological endgame, skipping over particularism and otherness. It is easier for diaspora liberal Jews today to imagine that the Jewish people can finally achieve our place in the world, and retain our moral character, by subordinating our nationalism rather than trying to compete for a place in a world of nations, and the occupation proves the point.

The Pauline trope helps explain two key dimensions of the film. Its insistence that young American Jews are lied to makes sense once one understands that the Jewish community has placed scales upon their eyes. And once the scales fall away and the truth is revealed—once one sees the horrifying truth that has been hidden—one must become an evangelist and bear the tragic burden of preaching the gospel, even at the cost of alienation from the community one seeks to transform.

To be clear, I am not suggesting, as some advocates of Israel unfortunately have, that Zimmerman and her allies are no longer Jews (or are now “Un-Jews”). Zimmerman and her allies believe that their critique of our community comes from their Jewishness—and they make no claims to be leaving. In fact, by the end of the film, the gauzy sequences of protests by IfNotNow (which Zimmerman cofounded) and others portray a different vision of Jewish particularism: the dissidents proudly wear tallitot and kippot; they sing Jewish songs. But identifying the Pauline trope that underlies the film helps us understand the story that its protagonists and creators want to tell about their journey from ignorance to enlightenment, from obscurantism to moral grandeur. This is not really a political story—one learns almost nothing about the history and politics of the conflict from this film—it is a story of personal spiritual transformation.

For the enlightened, everything that runs counter to their new narrative must be a lie. This naturally gives rise to conspiracy theories. How else can one explain how the plain truth has been hidden, except through the perfidy of deception? This assumption helps explain the surprising plot turn of the second half of Israelism. The film argues explicitly that the rise of Donald Trump, and therefore the emboldening of the white supremacist antisemitism, is the fault of the pro-Israel community in America. The rationale for this claim is offered by Simone at the film’s midpoint, when she concludes that the Jewish community believes that “the only way we Jews can be safe is if Palestinians are not safe.” Ultimately, the film argues, this belief has led the Jewish establishment to trade our safety in America for the safety of Jews in Israel, because President Trump could be counted on to support the Israeli government’s oppression of the Palestinians.

This argument blames the Jews for their own victimization and begins to make the film, in the words of a friend, “epistemically antisemitic.” Plenty of Jews blame other Jews today for the rise of antisemitism, so the argument here is not novel. The only irony here is that polarization in America has driven the rise of the antisemitism in America on both the right and the left, and the film is only too eager to help that trend along.

As a liberal Zionist, I aspire to be what Michael Walzer has famously called a “connected critic,” and I struggled watching Israelism and its translation of complexity into conspiracy. Entirely missing from the film was the majority of Jewish leaders and educators in America who know and teach about Palestinians and occupation, neither lying to their students nor concluding that Israel’s challenges require them to abandon their loyalties. Where, in Israelism’s world, are the majority of American Jews—and the majority of Israelis—who know the present is untenable but fear the alternatives? Or the parallel majority on the Palestinian side, who know that the path toward mutual safety and security lies in recognizing our inextricability? And what happens to us in this desperate attempt to generate mass appeal for the most populist and partisan version of our impossible story?

The filmmakers are taking this show on the road to campuses because they believe that young people in particular will identify with their story of having been deceived, but if my experience at Yale is representative, they may have underestimated their audience. In the talkback with the filmmakers, many of the students jumped on the breathtaking simplicity with which the film turned the Israel-Palestinian conflict into a morality tale. The first round of questions was about Israelism’s sins of omission: the Palestinian leadership’s refusals to negotiate, its failures of governance, the intifadas, its international campaigns of terror.

Moreover, if the producers had hoped to capture some of the rising tensions around the summer and fall protests in Israel against the government’s antidemocratic judicial reform overreach, they accidentally stumbled on a very different moment. On October 8, even before Israel’s military response to the Hamas invasion, pro-Palestine protests overtook the west; the climate on campus, at Yale and elsewhere, became hostile, even dangerous for many Jewish college students. Near the end of the film we see our now-happy, smiling protagonists leading anti-Israel protests against Jewish communal institutions, and you could hear audible gasps in the student audience. The film’s naive representation of good guys and bad guys and its entire plausibility structure collapsed as the Yale students thought about their own experience of the last few months. The subsequent trek of most of them—many of whom were not pro-Israel advocates—back to Hillel felt a little symbolic. They were choosing the difficult task of figuring out what it means to stay in a community rather than making a supposedly enlightened exit.

After October 7, there is mounting evidence that a lot of people are reawakening to a sense of themselves as part of the Jewish people, even if only faute de mieux. Enrollment in Jewish activities across America is up, Hillel and synagogue attendance are at all-time highs, and intermarried couples and Jews at the margins are digging into the ramifications of what it means to identify more fully as Jews.

I hope there is room in a bigger-tented Jewish community for trenchant critics of Israel. I think we can be resilient enough to sustain deep disagreement, especially about issues like the occupation that demand our scrutiny. But pluralism reaches its limits when it is asked to accommodate those who wish to destroy pluralism itself. The critique that Israelism offers is so unsympathetic and so disingenuous that even pluralistic Jewish communities must draw lines. Although I initially thought that Hillel might have been making a mistake in refusing to screen it, after seeing the movie, I understood their position. If Israelism wants us to leave a Jewish community that it considers irredeemably corrupt, it may need new institutions to spread its message.

The last several months have also reminded us that a different choice is available to modern Jews confronting the tension between their particular and universal commitments than the one Israelism offers. In his preface to Spinoza’s Critique of Religion, Leo Strauss wrote:

There is a Jewish problem which is humanly solvable: the problem of the Western Jewish individual who . . . severed his connection with the Jewish community in the expectation that he would thus become a normal member of a purely liberal or of a universal human society, and who is naturally perplexed when he finds no such society. The solution to his problem is return to the Jewish community, the community established by the Jewish faith and the Jewish way of life—teshuvah (ordinarily rendered by “repentance”) in the most comprehensive sense.

Enlightenment can just as easily be found in the comfort of an imperfect community, the choice of Strauss’s ba’al teshuvah, as it can be found in conversion to a chiliastic faith. American Jewish identity is in transition after October 7, but maybe the path to reentry is now better paved than the one to the exit. As compelling as Israelism imagines the rise of its own narrative to be, I wonder whether it missed its moment.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Failure of Reimagination?

We once worried about the faith of young American Jews; now we worry about their politics. It’s part of a long historical development we should resist because Judaism-as-politics isn’t enough.

After the Fall

Who would have believed things could fall apart so quickly in Israel? And yet, Halkin writes, “I am in a way more hopeful than I was last December.”

The Ethics of Protective Edge

How does one deal with Hamas, an enemy that has eliminated any trace of the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, except for the purposes of propaganda?

Simon Wiesenthal and the Ethics of History

Was Simon Wiesenthal an intrepid hunter of mass murderers? Or was he in fact more of a charlatan than a hero? Tom Segev's new biography of the most successful—and controversial—Nazi-hunter raises more questions than it cares to answer.

Gideon Reich

I enjoyed Yehuda Kurtzer's review but found the the following statement baffling:

"Or the parallel majority on the Palestinian side, who know that the path toward mutual safety and security lies in recognizing our inextricability?" Was this a rhetorical question? Sadly, to my knowledge, there is no such majority or even a significant minority.