Jews in Blue

On May 5, 1892, the insurance broker and former Civil War general Frederick George d’Utassy was found unconscious in a gas-filled hotel room in Wilmington, Delaware. He died the next day. The exact cause of death, like much of d’Utassy’s life, remains shrouded in mystery. After all, d’Utassy wasn’t his real name, and he wasn’t a real general.

One of the many colorful characters in Adam D. Mendelsohn’s gorgeously illustrated and groundbreaking new study of Jewish soldiers of the Union Army, d’Utassy was actually David Strasser. A Hungarian Jew with a knack for languages (he spoke twelve), Strasser left Hungary for Canada in 1855. There he posed as an ex-Austrian officer left poor by the 1848 Hungarian revolution. He worked as a fencing teacher, dance instructor, professor of foreign languages, and possibly the secretary to the governor of Halifax. From there, Strasser left for America to fight against slavery. Posing as a radical Hungarian count named Frederick George d’Utassy, he commanded a regiment of immigrants, including his brothers Carl and Anthony, which he named the “Garibaldi Guards” and who were known for their resplendent uniforms. The authorities eventually caught up to his many deceits, and he was court-martialed, found guilty, and served a year in Sing Sing. Naturally, upon his release, he promoted himself to general and entered the commercial insurance industry.

Though making sense of Strasser’s life is beyond anyone’s capability, Jewish Soldiers in the Civil War sorts through much else that is confusing, unknown, or simply untrue about the role Jews played in the Civil War. The volume, an unprecedentedly comprehensive and nuanced picture of American Jewry and American Jewish Union soldiers during the Civil War, draws upon the Shapell Roster, an ongoing project of the Shapell Manuscript Foundation, which is the most careful and exhaustive register of Jewish soldiers who fought for both the North and the South. Mendelsohn draws from its ongoing findings to offer narrative profiles of the Union’s Jewish Medal of Honor recipients and its deserters, triumphant and fallen, faithful and fictional. “Never before,” he notes, “had Jews joined a mass volunteer army— itself a relatively new historical phenomenon—in such numbers and with such enthusiasm.”

Integrating newspapers, letters, and diaries, the Shapell Roster and Mendelsohn’s book are a corrective to a well-meaning but deeply flawed earlier record of Jewish service. In 1895, Simon Wolf—a prominent Washington, DC, lawyer who had met President Lincoln, was appointed to a government position by President Grant, and befriended every subsequent president through Wilson—published a 550-page book called The American Jew as Patriot, Soldier and Citizen. At the volume’s center was a list of more than eight thousand Jews who had fought in the Union’s blue and gray, including their names, ranks, regiments, and sometimes even their pictures. Wolf ’s volume, which was more miscellany than unified book, was compiled in response to a letter to the North American Review magazine by a veteran who said that he could not “remember meeting one Jew in uniform, or hearing of any Jewish soldier,” and to many others, like the prominent antisemitic historian Goldwin Smith, who denied the patriotism of American Jews (or indeed the Jews of any country) in the North American Review and elsewhere.

Jews, Wolf responded, had drawn a “keen and responsive sense of duty” from their “Torah and Talmud,” which made them disproportionately likely to volunteer for the Union cause. The “proportion of Jewish soldiers [in the North was not] only large, but is perhaps larger than that of any other faith in the United States,” he wrote. Wolf claimed around 10,000 had served, though the number is now thought to be closer to 8,000. So far, roughly 1,200 Jewish soldiers on the Union side have been verified for the Shapell Roster, with research ongoing and a companion volume on Jewish soldiers of the Confederacy planned.

Jewish Americans were not alone in seeking to testify to the alignment between the practice of Judaism and the American project. A Jewish newspaper in the Grand Duchy of Hesse covered the recently ended war by telling its readers the story of Colonel Grün, an immigrant from central Europe who fought valiantly for the Union. Forced to ride into battle on Yom Kippur, Grün refused a canteen offered by his fellow cavalryman, replying “today is Yom Kippur [and] as a Jew, I am allowed to consume neither food nor drink.” The paper’s account concluded with Grün assembling a minyan in the hospital “under the thunder of the cannons,” with their recitation of the Shema arriving moments before word came in that victory had been achieved. “No Yom Kippur,” the writer enthused, has “been celebrated by Jews in such a way since the days of the Maccabees.” All of which, of course, was apocryphal.

Although the question of Jewish support for the Union cause was of obsessive interest to antisemites like Smith and defenders like Wolf, their participation was not an important factor in the war. “Despite their considerable sacrifices for the Union cause,” Mendelsohn writes, “it did not matter a whit for the fate of the war whether Jews fought.” Furthermore, “there was little that was distinct in why Jews joined the army. . . . The ebb and flow of enlistment seemed to follow the broader stream.” Nonetheless, Mendelsohn writes, “in ways visible and invisible to their fellow recruits and conscripts, the experience of Jews was distinct from that of other soldiers.”

Even as they tried to both do their duty and blend in, “Jews occupied an outsize place in the American imagination.” They were imagined to be villains in the hysteria over war profiteering. And newspapers in both the North and South portrayed Judah P. Benjamin, the Jewish member of Jefferson Davis’s cabinet, as “the rotund exemplar of Jewish perfidy.”

It is no wonder, then, that although many Jews enlisted as private individuals, Jewish support for the war was communally reticent, if not pareve. Philadelphia’s Rabbi Sabato Morais delivered a rousing sermon in November 1864 after recent successful battles by the North and Lincoln’s reelection—and members of his congregational board criticized him for it. The unruly trustees “would have stopped my speaking altogether,” he wrote, and then he took a three-month break from sermonizing.

Unified efforts to mobilize Jews on the home front “typically guttered after an initial flare of enthusiasm,” Mendelsohn writes. Larger-scale initiatives, including the call to establish a Jewish military hospital in Washington and a Jewish sanitary commission to provide care for soldiers in the field, also fizzled.

In July 1861, Joseph A. Joel enlisted in the Twenty-Third Ohio Infantry. He was eighteen and had arrived as an immigrant from England only a year and a half earlier. Twelve years later, he wrote to then-governor of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes, to thank him for transferring him from an antisemitic unit, in which he was bullied, to a more tolerant one. He even named his first son after him, Rutherford B. Hayes Joel. In one of the many moving letters pictured in Jewish Soldiers, Hayes replies to the news: “I am proud of your partiality and shall always regard with great interest the progress of the young gentleman. . . . Let him be as brave and honorable as his father and he will be a credit to his parents and namesake.”

Joel’s colorful account of the Passover seder he and his fellow Jewish soldiers had “in the wild woods of West Virginia” is among the most well-known anecdotes about Jewish soldiers in the Civil War. They used their wages to order seven barrels of matza and two prayer books from Cincinnati and sent out a team to forage the rest of the meal:

We obtained two kegs of cider, a lamb, several chickens and some eggs. Horseradish or parsley we could not obtain, but in lieu we found a weed whose bitterness, I apprehend, exceeded anything our forefathers “enjoyed.” . . . We had the lamb but did not know what part was to represent it at the table; but Yankee ingenuity prevailed, and it was decided to cook the whole and put it on the table, then we could dine off it, and be sure we had the right part. The necessaries for the choroutzes we could not obtain, so we got a brick which, rather hard to digest, reminded us, by looking at it, for what purpose it was intended.

Being soldiers, they “forgot the law authorizing us to drink only four cups,” leading to one claiming to be Moses, another Aaron, and another who “had the audacity to call himself Pharaoh,” each so drunk they eventually had to be carried back to the camp.

Though Mendelsohn questions the veracity of Joel’s Passover story, his battle scars were very real. At the Battle of South Mountain, Joel was shot in his right leg, arm, and shoulder, fracturing bones in each. One of his lungs was punctured, and he lost the tips of two of his fingers. Three decades later, his wife described him as hobbled by “inflammatory rheumatism in both his feet, the effect of the wounds in his legs.”

Joel’s famous story notwithstanding, Mendelsohn, in his skillful balance of statistics and individual stories, argues that it was extremely difficult for any semblance of Jewish practice to exist amid the war’s encampments:

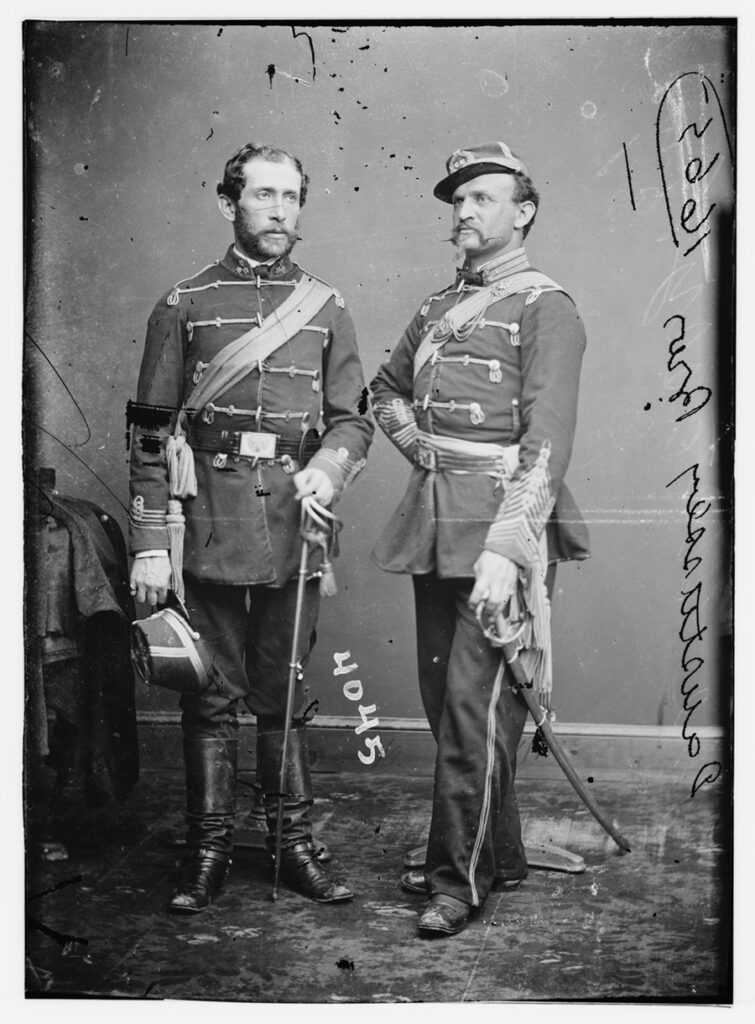

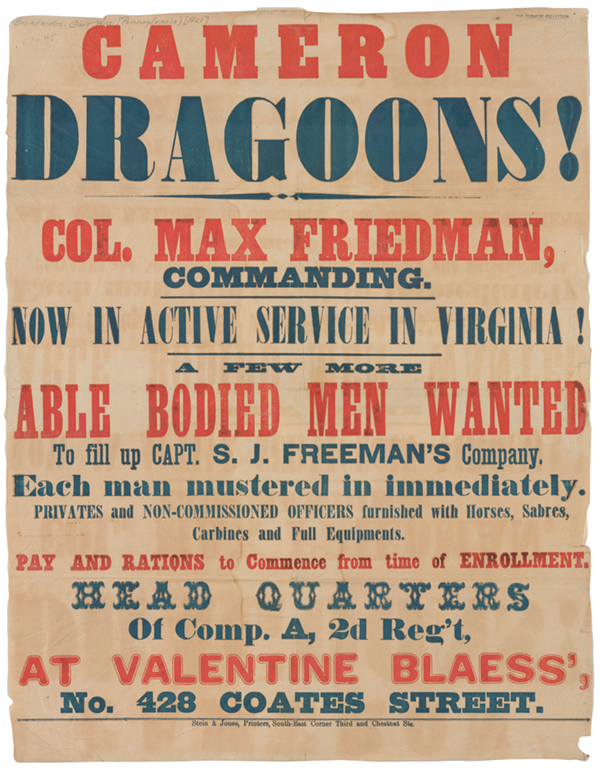

The tiny minority of Jewish soldiers were religious outsiders in an army that made few allowances for their needs. They were expected to subsist on a diet heavy on pork. Time for Sabbath observance was set aside on Sunday, not Saturday. Even in the Fifth Pennsylvania Cavalry, which initially had a Jewish colonel, Jewish officers and a Jewish chaplain, it was nigh impossible to faithfully observe Jewish religious traditions.

Furthermore, “military service immersed Jews among Christians in an environment suffused with Christian music, hymns, prayers, and preaching, with a shower of Bibles, tracts, and newspapers rained upon them by mission societies.”

Mendelsohn counts 293 Union regiments in which Jews served. Fewer than twenty-five of them had as much as a minyan, and there was never more than a “sprinkling of Jewish officers,” twenty-four of whom were surgeons.

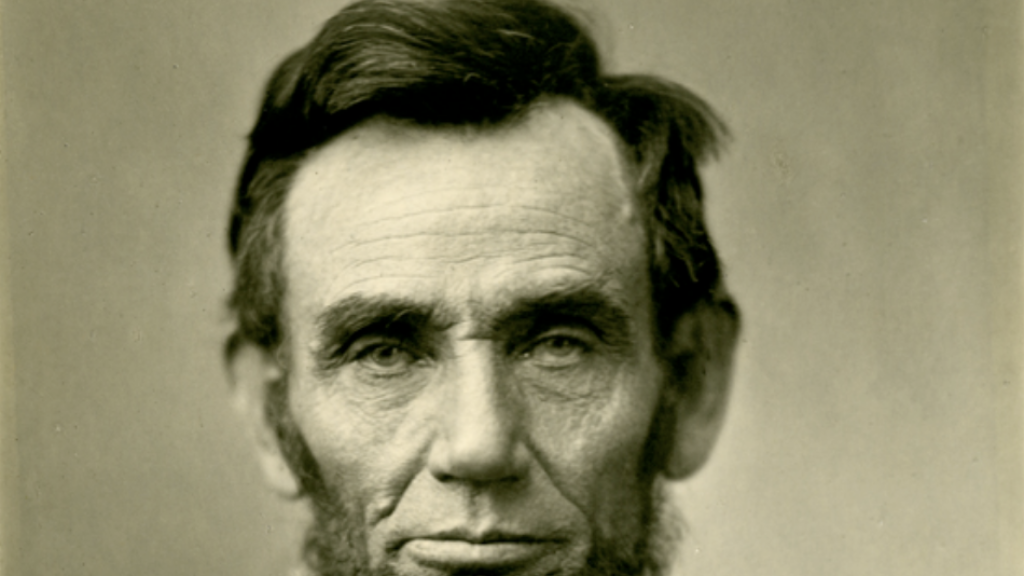

A Jewish surgeon named Lazarus Schoney served at the Armory Square Hospital in Washington, DC, where President Lincoln and the poet Walt Whitman would often visit soldiers recuperating from wounds sustained in the nearby battlefields of Virginia. Schoney, unlike Strasser, possessed actual credentials, including a PhD and rabbinic ordination from Prague. He once went three weeks without changing his clothes, sleeping on the floor of the hospital, during which time he “contracted a severe cold.” Lincoln, seeing the dedicated doctor in need of attention himself, told him, “You are a sick man too.” Schoney survived, ending the war as the chief contract surgeon with an office in the Senate Chamber. He returned to Europe to continue his medical studies before returning for a series of professorships.

After being widowed, the former rabbi married another American doctor, Theodosia Secor Fowler, who was Catholic. Here and throughout Jewish Soldiers in the Civil War, Adam Mendelsohn gives us early, vivid snapshots of the American Jewish story in all its complexity.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

When Freedom Began to Ring

How the land of opportunity became the opportune land for Jews to thrive.

The Abrams Case and Justice Holmes’ Philo-Semitism

In 1919 Oliver Wendell Holmes changed his mind and in so doing transformed the law of free speech.

Leviticus on the Fourth of July

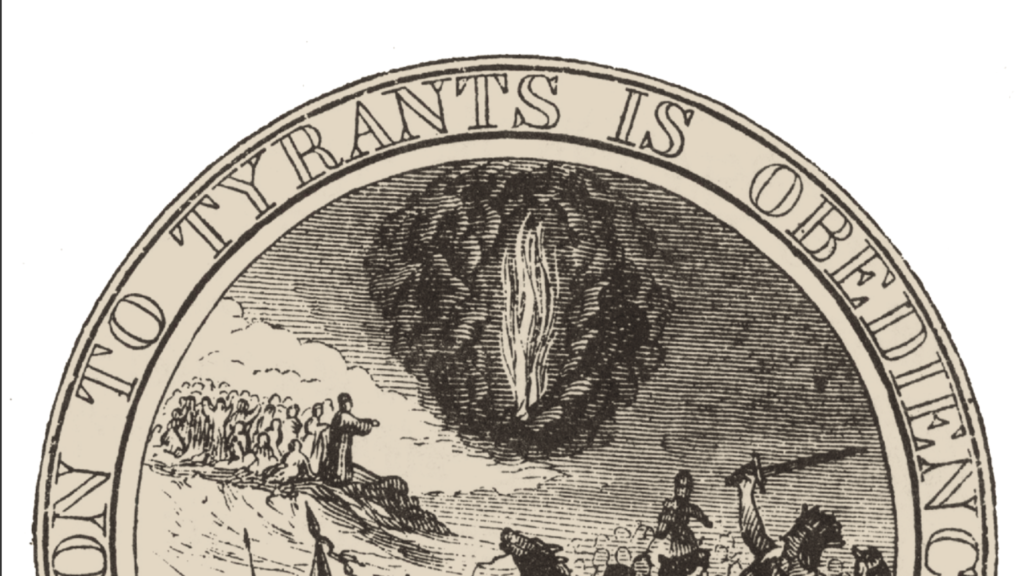

Biblical narratives and imagery have played a surprisingly large, even outsized, role in the formation of the American national consciousness and institutions.

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

Nancy Wallack

Just so you know, Joseph Joel is still inspiring Jews as we life. His account of his Union army Seder helped me cope when I was one of 40 Jews (including the children) living in Blacksburg (a few miles from the West Va border). We had to do and did everything to make a Jewish life. We told the IGA when to order Passover groceries. No bakery, so we made our own bread. Books we ordered from Philadelphia. The few families who kept kosher ordered from a butcher in Richmond, Va. And when I made a Seder there, I quoted from Joseph Joel's account. May his memory be for a blessing.