When Freedom Began to Ring

In his famous 1790 letter to the Jewish community of Newport, Rhode Island, George Washington wrote that “the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.” These words were not the kind of quid pro quo sometimes offered by European Enlightenment leaders of the time to Jews; it was not an implicit warning that they ought to behave themselves if they wanted to be tolerated.

President Washington, under whose leadership many Jews had fought during the Revolutionary War, was simply recognizing that America only required of its Jews what it required of all its citizens. At the founding, America was already not a Christian nation, and this was in large part because of its Jews.

Everywhere else in the world, prior to the American Revolution, Jews were disfranchised, politically isolated, and vulnerable. Even where they were relatively secure, such as in England, they were not full citizens. In 1775, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, English Jews could not vote, serve on juries, serve in Parliament, be military officers, attend a university, engage in some businesses, become barristers, or practice some other professions. Jewish immigrants had to pay special “alien” taxes forever, because they could not naturalize. And as aliens, immigrant Jews were prohibited from owning real estate or seagoing vessels, and from engaging in colonial or foreign trade.

Things had been somewhat better in England’s North American colonies, where momentum toward full equality built as the Revolution grew nearer, in part because of Jewish support for the patriot cause. In 1765, ten Jewish merchants in New York City, along with nearly two hundred Christian businessmen, signed a non-importation agreement to boycott British goods. Jewish merchants in Philadelphia and Newport, signed similar agreements. Others, most famously Haym Salomon, joined the Sons of Liberty. Gershom Mendes Seixas, the spiritual leader of New York’s Shearith Israel—the first synagogue in what became the United States —actively supported Independence. In 1774, Francis Salvador had won a seat in South Carolina’s Provincial Congress. He was reelected in 1776, thus becoming the first Jewish elected public official in the new United States. He served until he was killed in battle that August.

Most Jews in New York, Philadelphia, Newport, Charleston, and Savannah—where the Revolution was brewing—joined the cause early. In doing so, they staked their claim to political equality as a right, not a set of privileges to be granted.

As they did nowhere in Europe, Jews served as officers in the patriot armies. Mordecai Sheftall, a Savannah businessman, was a full colonel, then the third highest rank in the American army. David Salisbury Franks rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, served as a diplomat to France and Morocco during the war, and later became the assistant cashier of the Bank of the United States. Solomon Bush, whose father had signed a non-importation agreement, ended the war as a Lieutenant Colonel and the deputy adjutant-general of the Pennsylvania militia. His younger brother, Captain Lewis Bush, died in combat. There were no Jewish officers in the British army or among the Hessian mercenaries during the Revolutionary War. (However, Alexander Zuntz, a Hessian civilian commissary, served as the Hazzan of Shearith Israel congregation while the British occupied New York City. Impressed with American religious liberty, he stayed in New York after the war, and eventually became president of the synagogue.)

In the independent United States, every new state constitution granted Jews the right to vote, though nine of the first eleven of them originally limited office holding to Protestants or Christians. A few states retained established churches or special state benefits for some faiths. Religious tests for office directly denied Jews full political equality. These state establishments did not deny Jews religious liberty or legal rights, but they made them (and members of other non-favored faiths) less than equal citizens. This situation, however, was not destined to last very long.

When Pennsylvania’s 1776 constitution, for instance, required state legislators to “acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration,” the state’s Jews protested. Members of Philadelphia’s Congregation Mikveh Israel studied and annotated all state constitutions, noting where Jews faced discrimination, and then published letters in newspapers calling attention to the new constitutions’ objectionable features. In late 1783, Philadelphia’s Jewish leaders petitioned the Pennsylvania government to allow Jews to hold public office. Seven years later, Pennsylvania’s new constitution removed the religious test for office holding.

In 1787 Congress, operating under the Articles of Confederation, passed the Northwest Ordinance, the forerunner of subsequent laws regulating the settlement of western territories and the creation of new states. The Ordinance provided for “extending the fundamental principles of civil and religious liberty” in the national territories. Written before the Constitution, this was the first national guarantee of religious freedom. The Confederation Congress, which included no Jews and only the occasional Catholic, could have easily established some kind of non-denominational Protestantism or Christianity. But it did no such thing.

In that same year, on behalf of Congregation Mikveh Israel, Revolutionary War veteran Jonas Phillips wrote to George Washington, who was then serving as the presiding officer of the Constitutional Convention, requesting the Convention protect Jewish political rights. As it turned out, the Convention had already agreed to prohibit religious tests for office holding, but the willingness of Philadelphia Jews to lobby for their rights further illustrates American Jewry’s newfound boldness.

On July 4, 1788, Philadelphia held a parade to celebrate the ratification of the new constitution. The Grand Federal Procession was led by an interfaith group of clergymen, including a rabbi, their arms interlocked. Later, when George Washington took the first presidential oath of office in New York City, Hazzan Gershom Mendes Seixas joined other clergy from the city as a witness.

The First Amendment, ratified in 1791, confirmed the right of religious free exercise for all Americans and guaranteed separation of church and state. Under the Constitution, Jews held federal offices, even where they could not hold offices under existing state constitutions. Thus, in 1801 President Thomas Jefferson appointed Reuben Etting to be the US marshal in Maryland, even though he would not have been allowed to hold any office under that state’s constitution until 1826. Joel Hart and Mordecai Manuel Noah served as diplomats under Jefferson and Madison. Noah was later the sheriff of New York City, the “boss” of Tammany Hall, and a local judge.

The Constitution did not preclude individual states from barring Jews from public office. Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Jersey repealed these rules before the Civil War, while North Carolina did so during Reconstruction. New Hampshire finally abolished the practice in 1877. Nor could the constitutional expansion of Jewish rights end social antisemitism. Antisemitism, rooted in Christian theology, nationalisms, bigotry, private fears and ignorance, and the rantings of demagogues and conspiracy theorists, will, of course, never be abolished by government decree. A political system can regulate behavior and even promote tolerance, but cannot end private intolerance and hatred. In the Old World, however, anti-Jewish prejudice was often encouraged, supported, or even mandated, by governments. In America, from the outset, the law was on the Jews’ side.

Furthermore, America’s unprecedented acceptance of the Jews helped to induce other western nations, including Revolutionary France and mid-nineteenth-century Great Britain, to grant Jews similar rights, although the process in both countries was piecemeal, halting, and incomplete for many years. In Britain, for example, Lionel Rothschild won multiple elections to Parliament starting in 1847 but was unable to take his seat until 1859, after the Jews Relief Act had been passed. Full Jewish political equality in Britain was not achieved until 1871.

As we approach the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, on July 4, 2026, it is important to recall how the patriotism of Jews led to their political equality and a national policy of religious liberty. The United States became the first western nation to prohibit any religious test for national public office, have no national or official faith, have no laws restricting Jewish secular life or religious observance, and allow for freedom of worship and belief on a broad national scale.

When George Washington wrote to the Newport Jewish community, this process was not yet complete, but the holdouts were few and relatively insignificant. The Revolutionary era set the stage for the ensuing two and a half centuries of Jewish flourishing in a country where, to return again to the words of Washington’s historic letter, minorities enjoy religious freedom not because mere tolerance has been extended to them but because “all possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.”

Suggested Reading

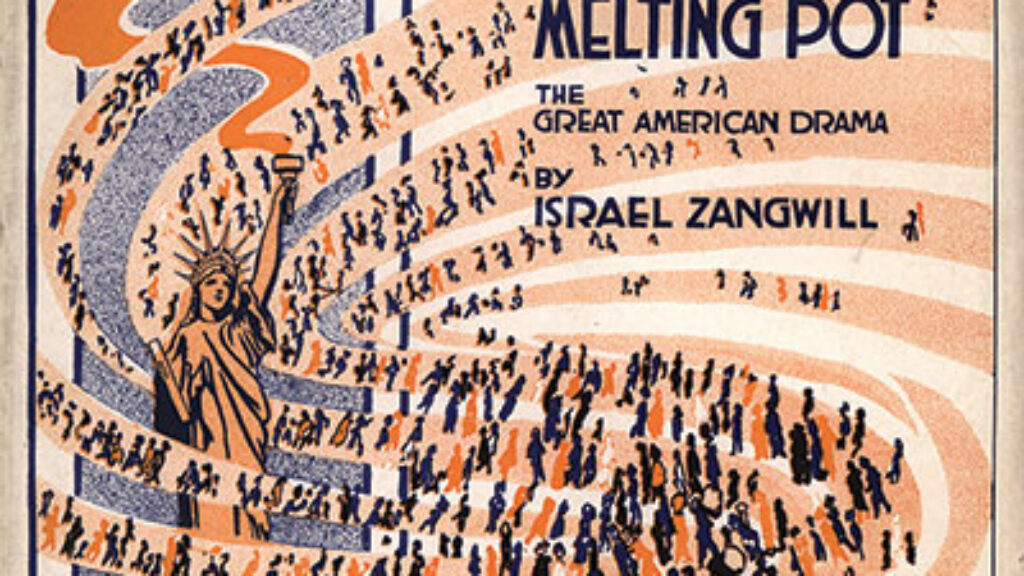

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

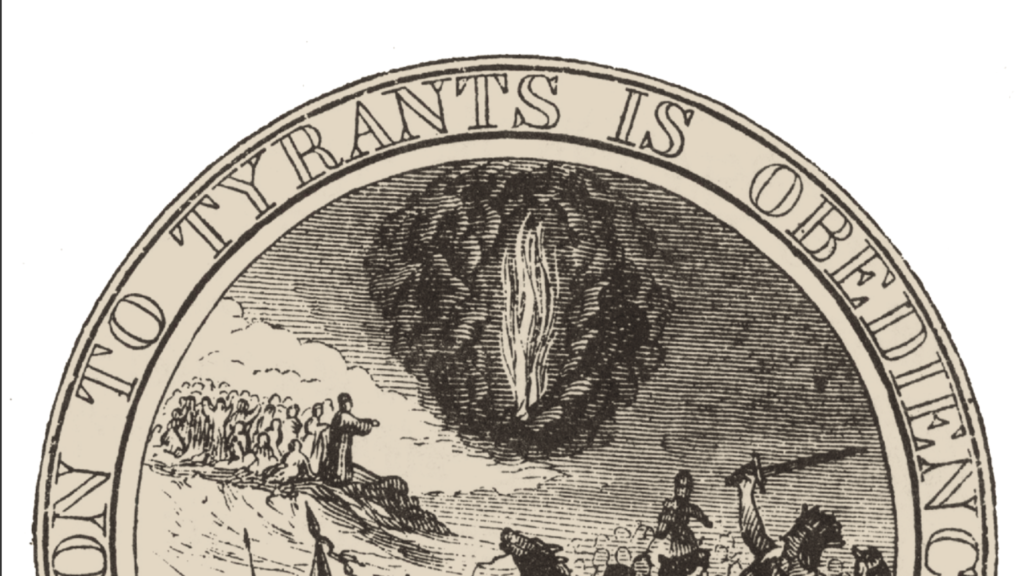

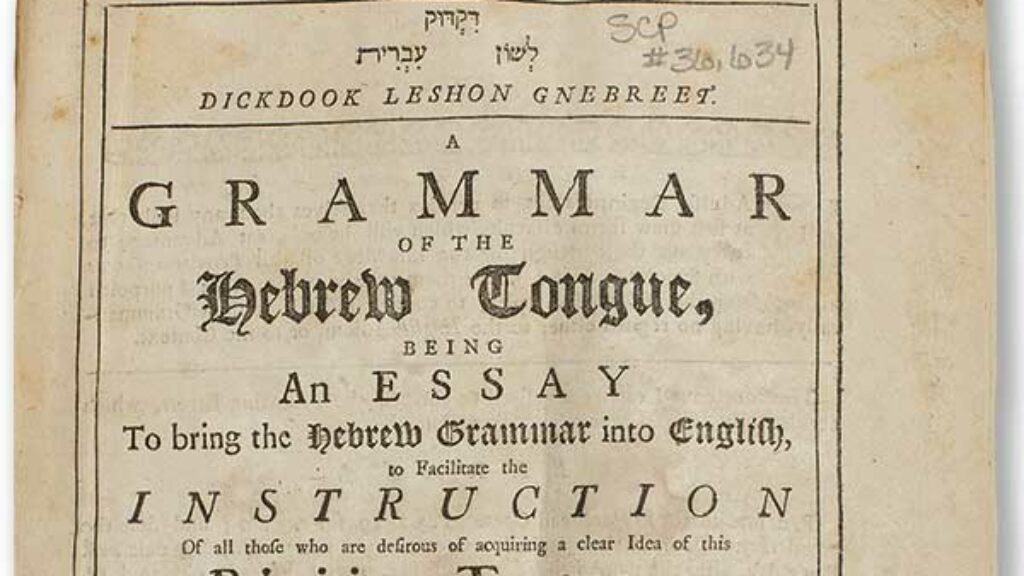

Leviticus on the Fourth of July

Biblical narratives and imagery have played a surprisingly large, even outsized, role in the formation of the American national consciousness and institutions.

Inventing American Judaism

Unlike the Jews of Venice, whose charter was anxiously renegotiated every decade or so, American Jews participated in civic life, confidently building themselves a future.

A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

Despite all of Bob Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he really was a child of the American heartland. Winning the Nobel Prize might actually be his most Jewish achievement.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In